THE ART EXHIBITION ‘LANDSCAPE OF EMPTINESS’ SHOWCASES SANITAS PRADITTASNEE’S ARTWORKS WHICH REPRESENT THEIR EXISTENCE INSIDE THE EMPTINESS

TEXT: TUNYAPORN HONGTONG

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

In the vibrant chaos of a tourist hotspot exists a veritable universe of elephant pants where the air is thick with the smell of cigarette smoke and international brands of perfumes. The crowd, herded onto peculiar wheeled trams (due to their lack of rails) mingles with the calls of tuk-tuk drivers seeking passengers and the surreal sight of angels wandering the earth. These angels, actually tourists adorned in traditional costumes, meander through their own sea of selfies, adding to the cacophony. Amidst all the mayhem the ‘Landscape of Emptiness’ exhibition by Sanitas Pradittasnee at the Art Centre of Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra, offers a temporary sanctuary to gain a brief peace of mind.

Immersing oneself in art is a precious pause—a moment of stillness where all senses are engaged, sharply tuned to the here and now. Yet, stepping out of the gallery and slipping back into the everyday—following the same routine—a lingering question surfaced days later as I sat down to pen this piece: What stirred those profound moments of tranquility? Could it truly be the ’emptiness’ as the exhibition’s title, ‘Landscape of Emptiness,’ suggests?

The answer I found is both yes and no. The ’emptiness’ encountered in that gallery space isn’t about absence or a void. Rather, it’s a palpable emptiness, a presence shaped by existence itself.

In ‘Landscape of Emptiness,’ Sanitas Pradittasnee revisits her signature palette of materials—clay, glass, and metal, among others. The shapes too echo her past with forms like pagodas and stupas asserting their existence. Yet, this current collection marks a departure in its sculptural minimalism: each piece embodies less “objectness” than ever making them lighter, less voluminous. Even though her previous work, ‘Garden of Silence,’ seemed to dissolve into its surroundings, it retained a substantial material presence. Despite this pared-down objectness, the enduring forms remain intact, unaltered. In a striking shift, the iconic pagoda now arises not merely from solid materials but emerges through interwoven physicality and voids.

‘Silence’ is the first installation that viewers encounter upon ascending to the second floor of the gallery. This piece distinctly exemplifies form creation from objects and the surrounding void. The installation arranges multiple brass bells, each suspended from a round wooden panel overhead, with varied lengths, floating ethereally, creating an aerial form reminiscent of a floating pagoda base and imparting a sense of lightness and transparency.

Within the enclosed space, where no wind can stir, these bells, designed to produce sound, hang silently— inert and unmoving, not fulfilling their intended function. But in this stillness, the artist, with the consultancy of Kullakaln Gururatana, has designed lighting that casts shadows of each bell onto the gallery’s white walls and wooden floors. Sketching out another pagoda the “intangible” shadows are formless yet they emerge from “tangible” objects.

Personally, ‘Silence’ was where I lingered longest in the show, drawn inexorably to its shadows. These shadows are not only integral to the artwork’s narrative, amplifying the concept the artist intends to convey, but they also possess a pristine beauty and a tranquil aura that arrests and ensnares the observer, binding us to the spot. These shadows also beautifully coexist with the surrounding space, the shadow of the stair railing and harmonizing with ‘Impermanence,’ a painting steeped in dark, enigmatic tones and strategically positioned in the stairwell to share the same visual plane as the installation’s cast shadows. ‘Impermanence’ itself is a concoction of the earth—crafted from soil, dust, ash, and the latex of the River Tamarind tree. It is smoked over Palo Santo wood, an ancient ritual of the Inca tribes believed to purge negativity and restore tranquility and balance1.

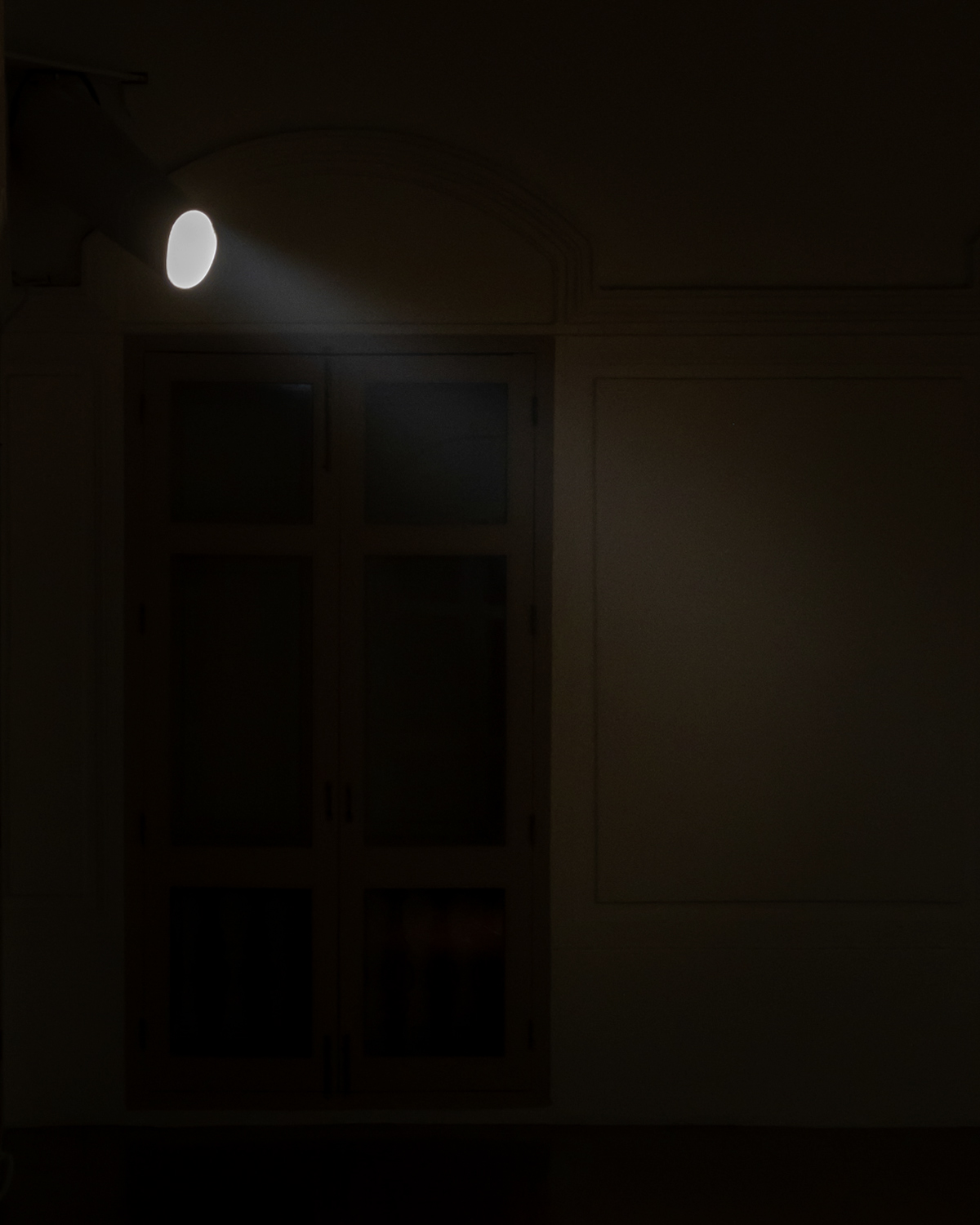

Adjacent to ‘Silence’ is an empty room with no objects. It is illuminated by a single spotlight from one corner, under which countless tiny dust particles float in the air. Upon closer inspection, the wooden floor of the gallery, where the light falls, reveals numerous footprints likely left by the artist, the crew, staff, and previous visitors. This is the artwork titled ‘Stardust, or we are…,’ a piece completely devoid of physical objects.

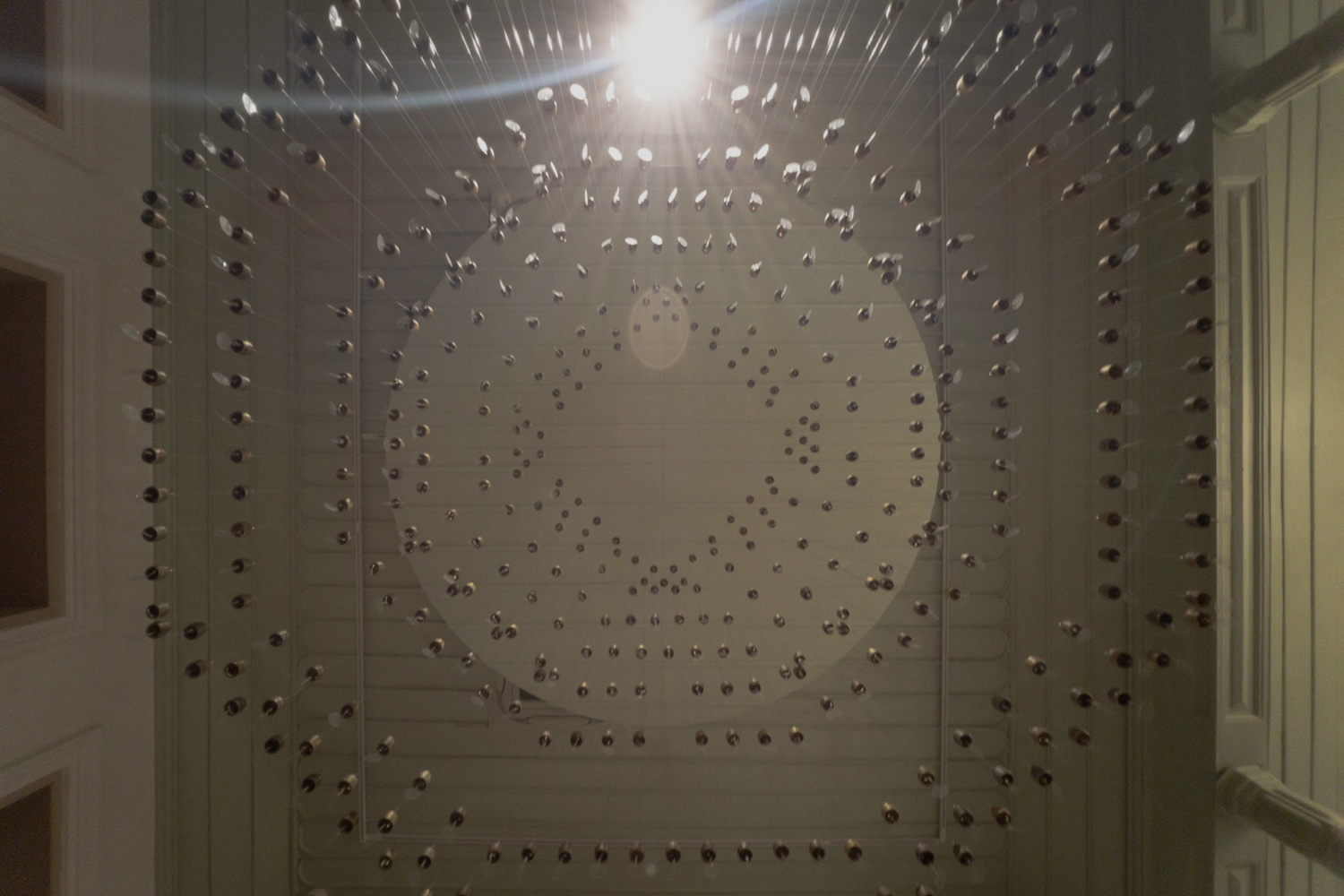

In the installation titled ‘Shadow of Emptiness’, Sanitas casts various small objects collected from different places, such as plastic spoons and forks, Yakult bottles, flowers of the Indian cork tree, and leaves into brass. They are suspended from the ceiling in a spherical formation resembling a stellar explosion of the Big Bang, with a brightly shining light at the center, akin to the sun. This arrangement casts sprawling shadows across the ceiling, walls, and floor of the room. Although the shadows are the most visually striking element, the brass casting process that the artist has chosen to employ is perhaps the most intriguing aspect.

Both in ‘Shadow of Emptiness’ and ‘A Frog in the Mud’—a sculpture of a frog displayed on a charred wooden log on the lower floor—Sanitas utilizes the traditional Lost Wax casting technique, a local craftsmanship from Ban Pa-Ao, Ubon Ratchathani Province in Thailand. Traditionally, this method involves using a wax model to create a mold for the molten metal, which then solidifies into the sculpture, causing the wax to melt and dissolve away in the casting process. However, for this exhibition, Sanitas uses actual found objects and the organic remains of a frog she accidentally discovered as molds. Consequently, when the brass sculptures are formed, these objects and remnants vanish, suggesting that the artwork only truly comes into existence as these original forms disappear.

The Lost Wax metal casting method and the Big Bang introduce another layer of dualism that Sanitas has embedded in this exhibition: “birth” and “death.”

In Buddhism, the world is not viewed through a lens of dualism that categorizes reality into opposing poles such as good/evil or dark/light. Instead, it adopts a non-dualistic approach, which posits that we cannot reject one aspect in favor of another since everything in the world is interconnected2. Without light, there would be no dark shadows, and without darkness, light would not be discernible. These contrasting poles are also linked through constant transformation, much like the Lost Wax technique used by Sanitas, which embodies both “birth and death” and “death and birth,” in a continuous cycle. This concept is present in ‘Primitive,’ where the artist fills the lower gallery room with soil and ash, crafting a vast, barren and unknown table filled with soil and ash, evoking a desolate landscape. The mirrored walls around the room render a shimmering, blurred image, with the soil symbolizing both the historical state of this space before its transformation into an art gallery and its future, reinforcing the notion that everything must eventually return to nature.

There are three additional rooms in the exhibition that I have yet to discuss: ‘Follow the Sun’, ‘Follow the Moon’, and ‘The Present Moment’. These spaces are crafted by the artist as serene areas for visitors to spend time in introspection. The first room captures the natural light and ambient sounds of the morning. The second, shrouded in near total darkness, envelops visitors in the sounds of nocturnal insects and the earthy scent of the forest (the artist recorded these sounds during a meditation retreat and collaborated with Architapon Parntong to create a fragrance that closely matches those memories. A multitude of scents filled every square inch of the gallery, standing out as a significant feature of the exhibition, effectively masking the old library smell of the building—a scent that, I couldn’t help but think, had previously been alongside with the artworks displayed here). The final room, with mirrors seamlessly integrated into the doors, invites visitors to reflect inwards.

Personally, I found these three rooms to be my least favorite in the exhibition, especially the first two. They appeared as an attempt to distill and replicate the artist’s own experiential revelations for the audience. Yet, I contend that the journey to meditation, mindfulness, or the sought-after state of emptiness cannot be created with a template. Individual paths to such revelations are as varied as the individuals themselves—some may find this through sports, electronic music, or even immersing in a few select pieces of fine art. Although these two rooms offered a tranquil atmosphere with pleasantly curated light, sound, and scent, as an observer, I already felt a sense of peace and an almost meditative state from the moment I stepped into the exhibition.

‘Landscape of Emptiness’ is currently on display at the Art Centre of Silpakorn University, Wang Tha Phra, from March 22 to June 8, 2024.

1 ‘The Magic of Palo Santo. Accessed 17 January. modernom.co

2 Phengchan, Pramuan. Philosophy of the Prajñāpāramitā-Hṛdaya Sūtra’. Sook Publishing, 2022.