An architect who always developed architectural designs through research RESEARCH ABOUT HIS PERSPECTIVES ON DESIGN RESEARCH REFLECTING ON PAST PROJECTS AND HIS ADVICE FOR YOUNG ARCHITECTS IN THAILAND

TEXT: CHIWIN LAOKETKIT

PHOTO CREDIT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

If life is a journey, then it is a road shaped by an emerging architect, one whose path unfolds in the quiet hours between day and night. This is the story of Jenchieh Hung, who worked alongside the renowned architect Kengo Kuma, refining his craft and developing a distinctive architectural style of his own. Driven by a dream to transform the architectural landscape, Jenchieh Hung travels far and wide, fueled by his passion and a deep concern for the history of creators and the evolution of Asian architecture.

(Left to right) Jenchieh Hung, Kulthida Songkittipakdee, they are serving as exhibition chairman and principal curator for The Association of Siamese Architects under Royal Patronage (ASA) | Photo: ASA

In time, he co-founded HAS Design and Research with Kulthida Songkittipakdee, designing innovative spaces across Thailand and China. Since 2019, we’ve come to know Jenchieh Hung as a visiting professor at Tongji University—an architect who constantly challenges conventional thinking with thought-provoking questions about the essence of architecture. He is also a curator for major architectural exhibitions, contributing to some of the most influential design festivals

Jenchieh Hung is serving as a visiting professor at Tongji University | Photo: Hung And Songkittipakdee Laboratory (HAS Lab)

Kulthida Songkittipakdee, Chana Sumpalung, and Jenchieh Hung at the Infinity Ground Architecture Exhibition at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) | Photo: ASA

Jenchieh Hung is the exhibition chairman and principal curator at The Association of Siamese Architects under Royal Patronage for the Asian Contemporary Architecture Exhibition | Photo: ASA

Recently, art4d had the opportunity to sit down with him, delving into his perspectives on design research, reflecting on past projects, and gaining invaluable insights into the future of architecture. His advice resonates not only with young architects in Thailand and China but with anyone eager to understand the evolving trends shaping architecture across Asia.

art4d: How do you think HAS Design and Research differs from other architectural firms?

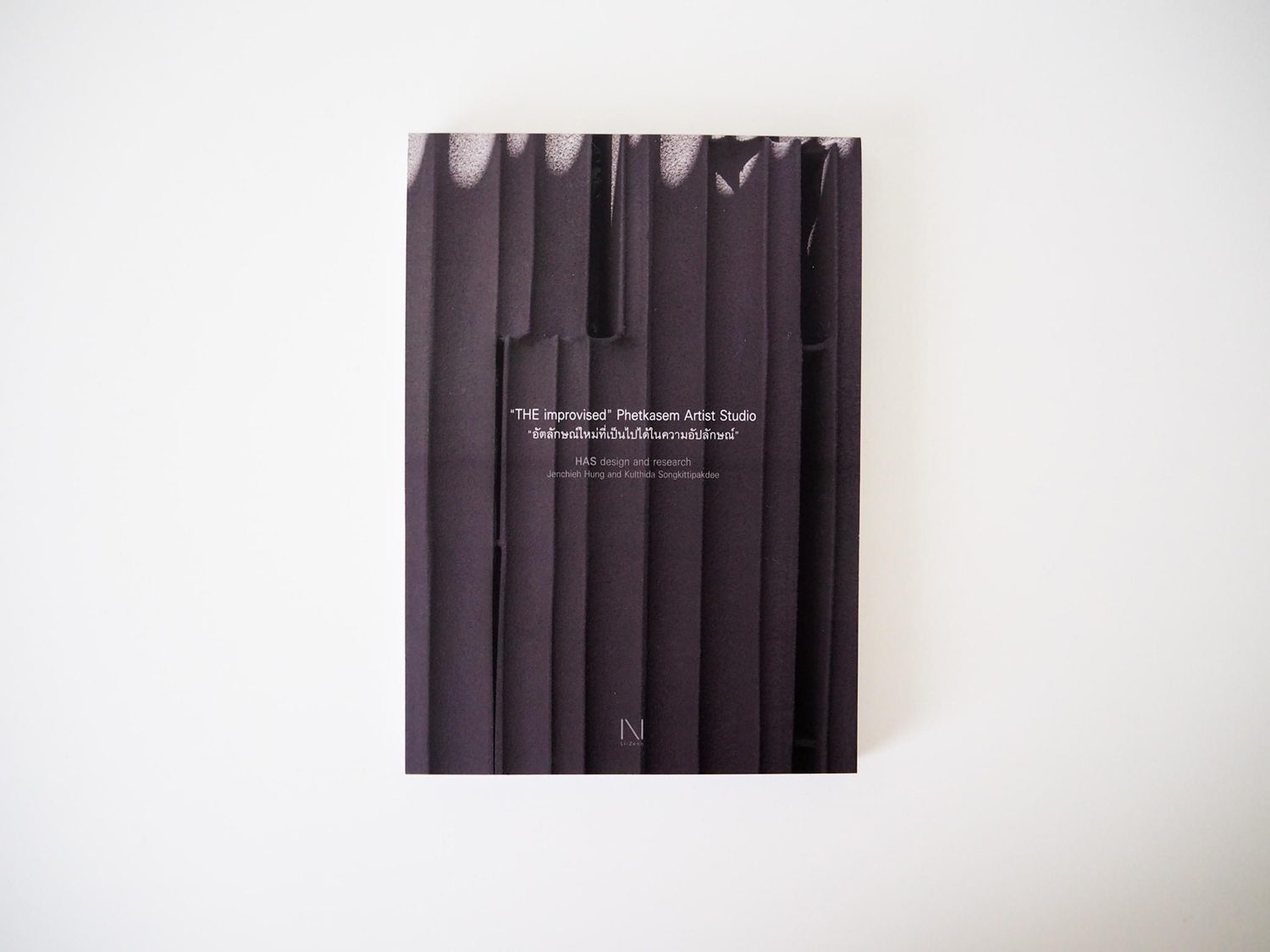

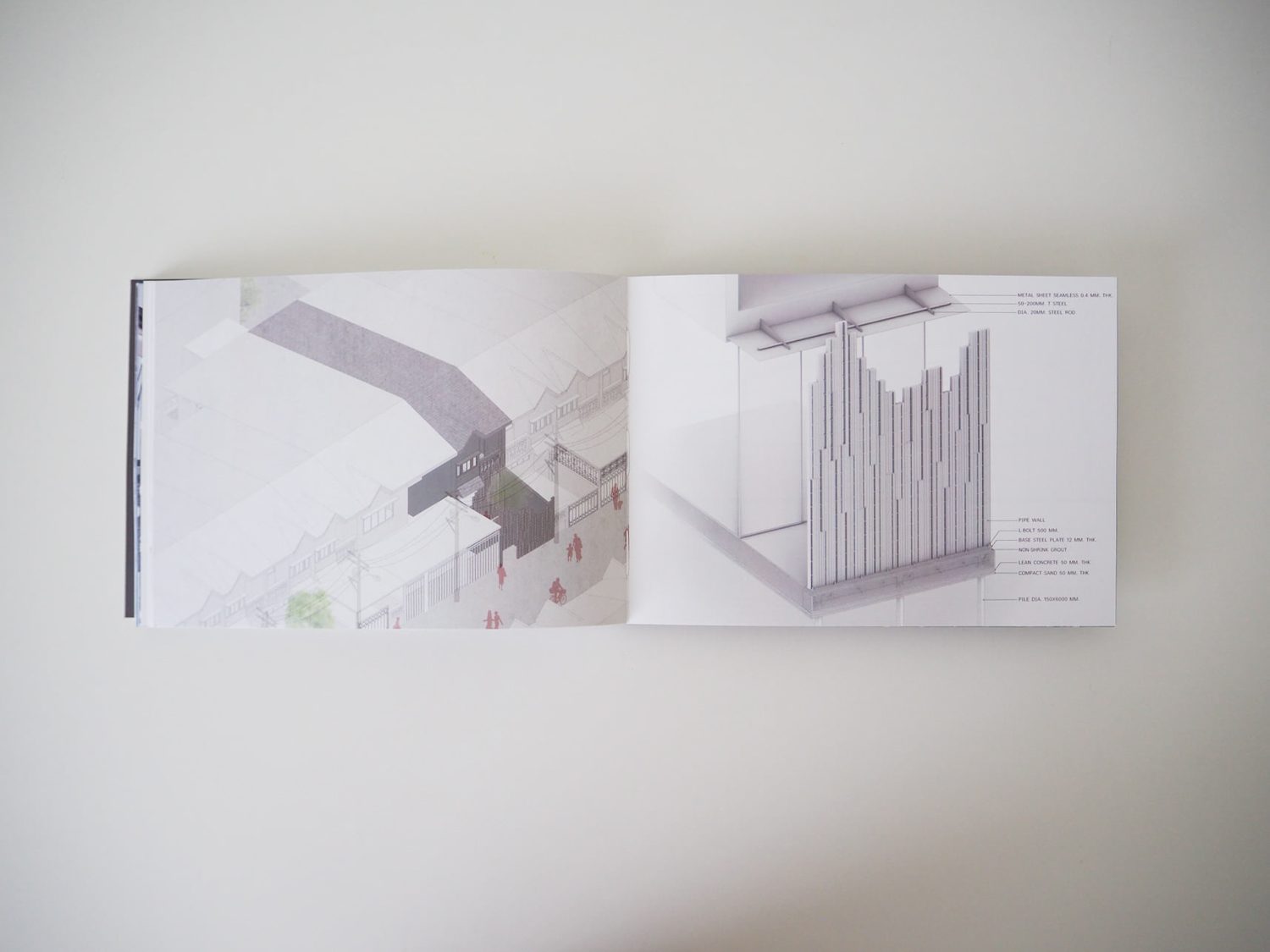

Jenchieh Hung: Four years ago, we published a book titled THE improvised: Phetkasem Artist Studio, which highlighted our work and explored the themes of improvisation and the study of local Thai villages. Over time, Hung And Songkittipakdee (HAS) have distilled some of the key concepts of Asian architecture into three guiding philosophical principles, which have come to define our approach.

The first is Improvised. We decided to publish this book because we realized that many of the buildings we design evolve over time, adapting to changing circumstances. For us, improvisation is not just a design principle, but also a reflection of the surrounding environment. In many local communities, people often improvise with their buildings to make them more attuned to their context, which leads to a more sustainable way of living. This adaptability is key to ensuring that architecture can respond to both the environment and the people who inhabit it.

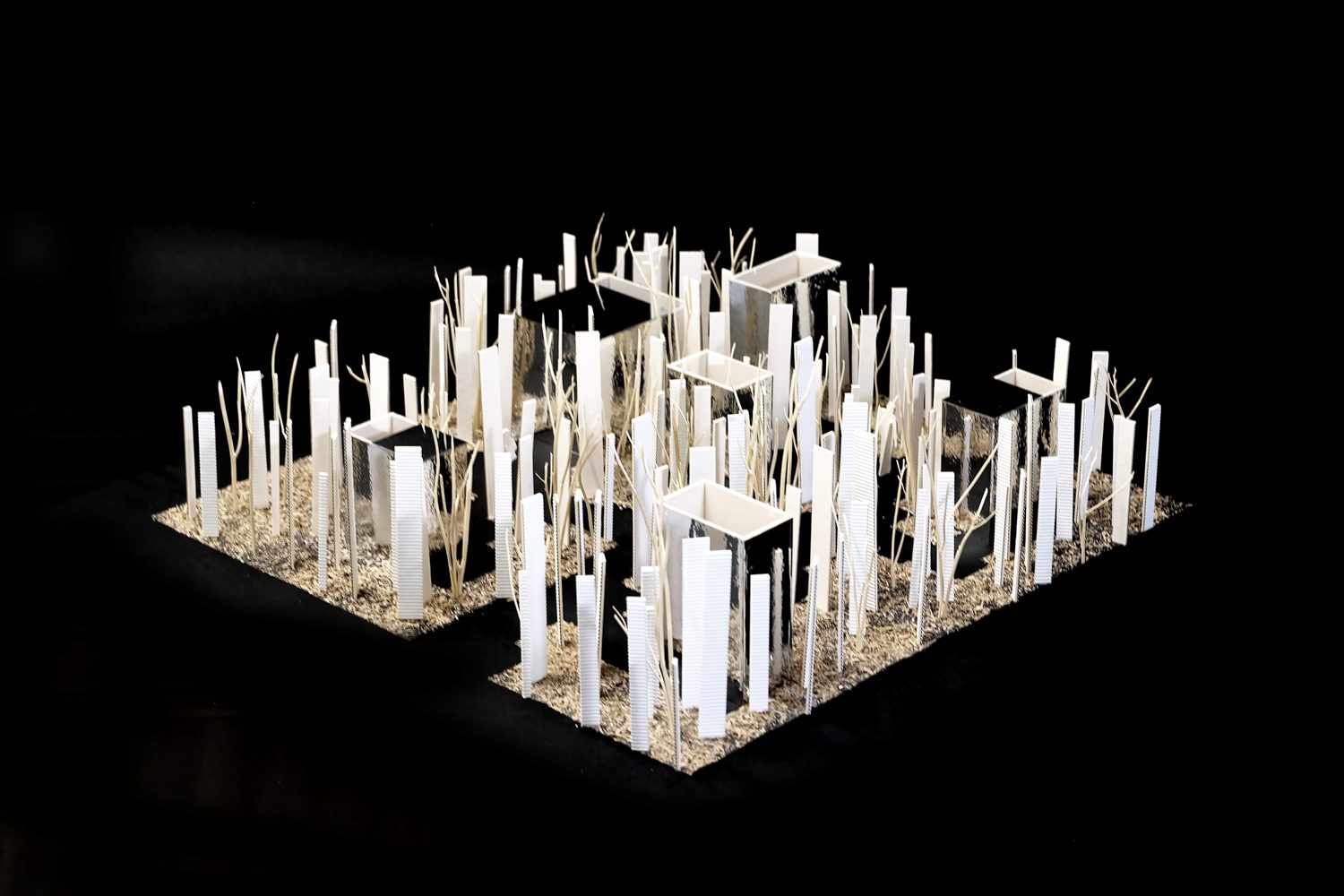

Bangkok Phetkasem Village | Photo: Hung And Songkittipakdee (HAS)

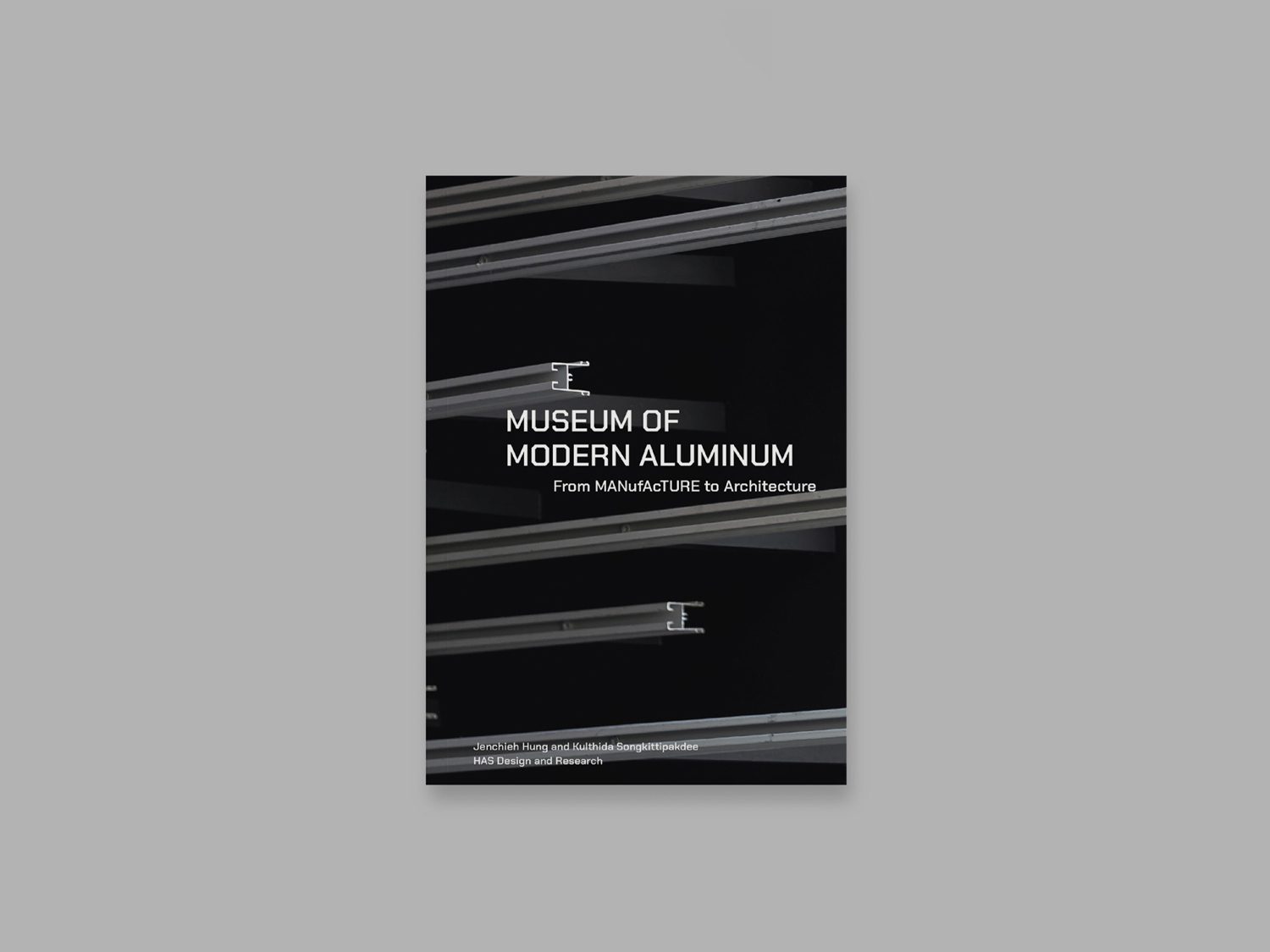

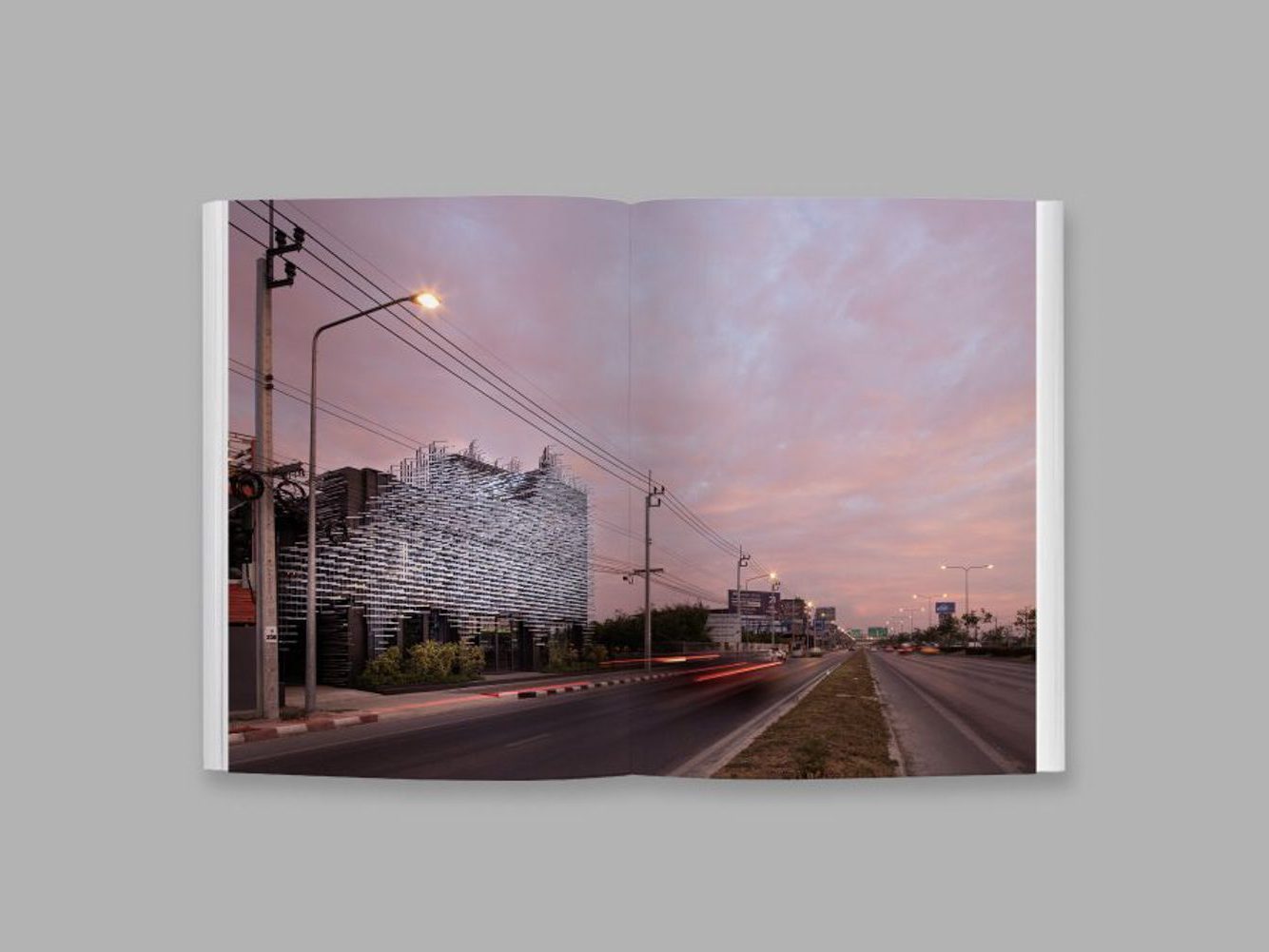

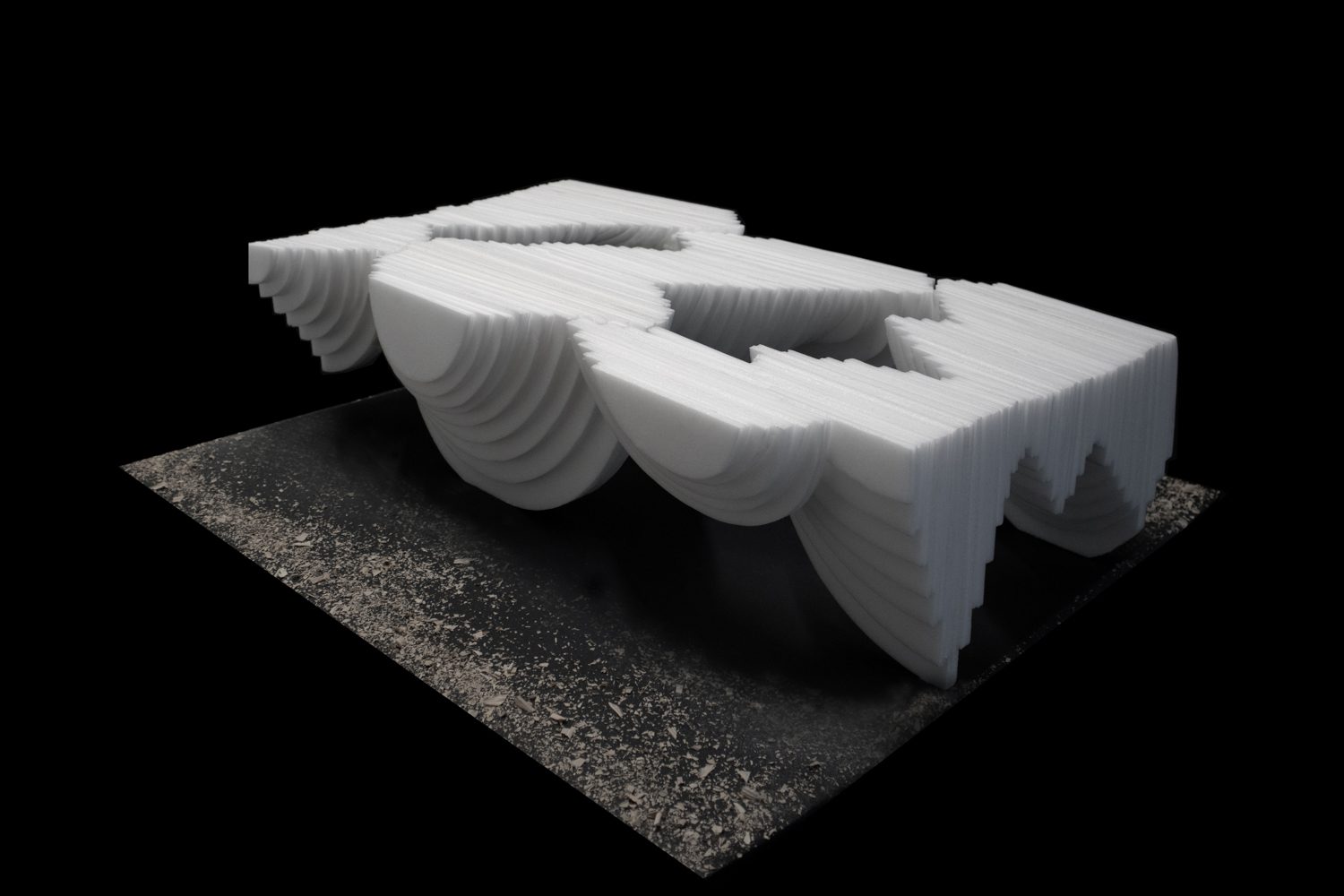

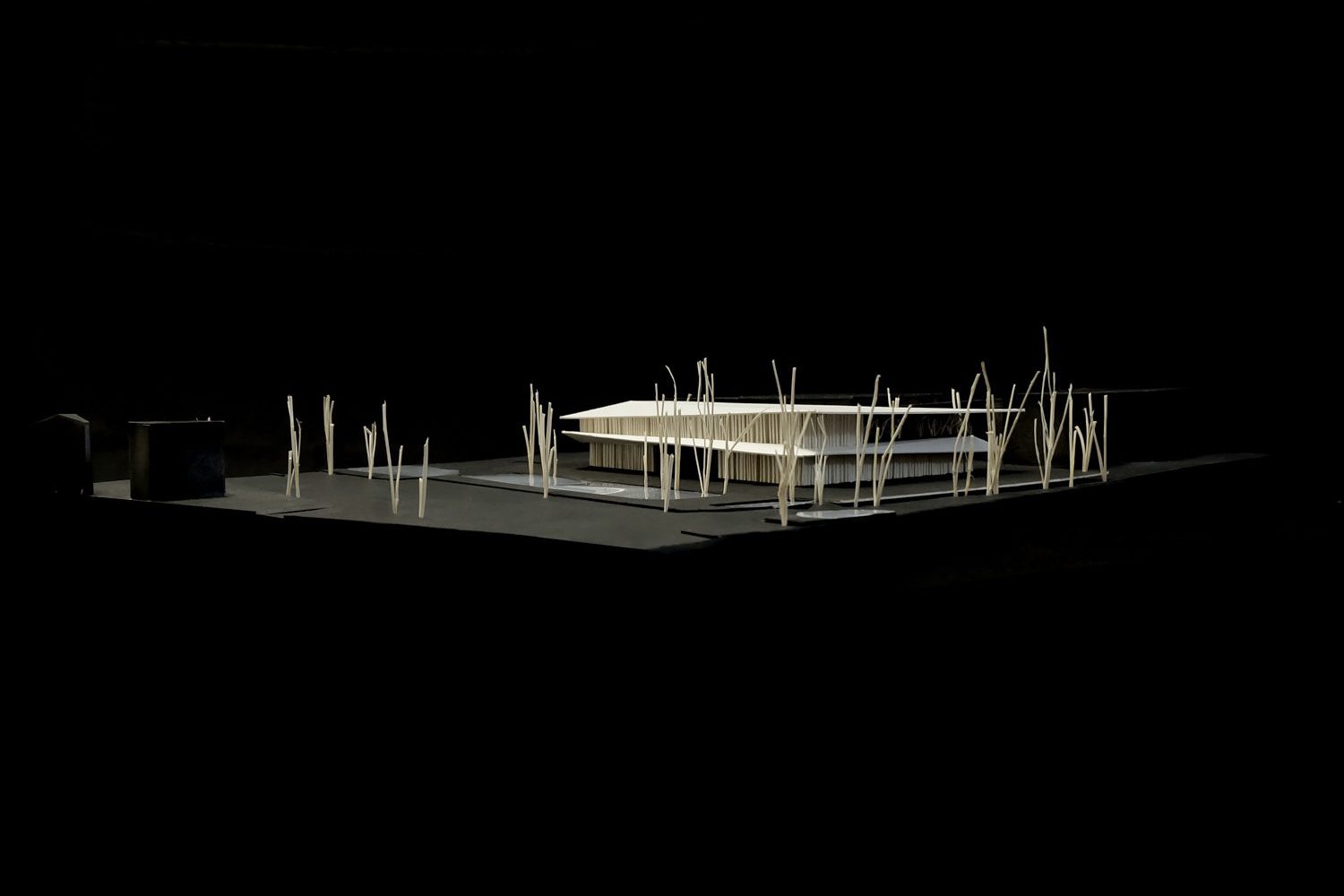

The second principle is Manufacture (or, as we like to call it, MANufAcTURE). While this term traditionally comes from the industrial world, we reinterpret it through the lens of the relationship between HUMAN and NATURE. We believe that both are essential to maintaining a balanced urban ecology. Cities, often dominated by concrete and seemingly disconnected from the natural world, can benefit from the inclusion of open, non-functional spaces that allow nature to flourish. By integrating natural elements into urban planning, we create a more harmonious and livable environment. The presence of nature within the city not only enriches the built environment but also fosters a symbiotic relationship between humans and the natural world.

Bangkok Floating Canopy | Photo: Hung And Songkittipakdee (HAS)

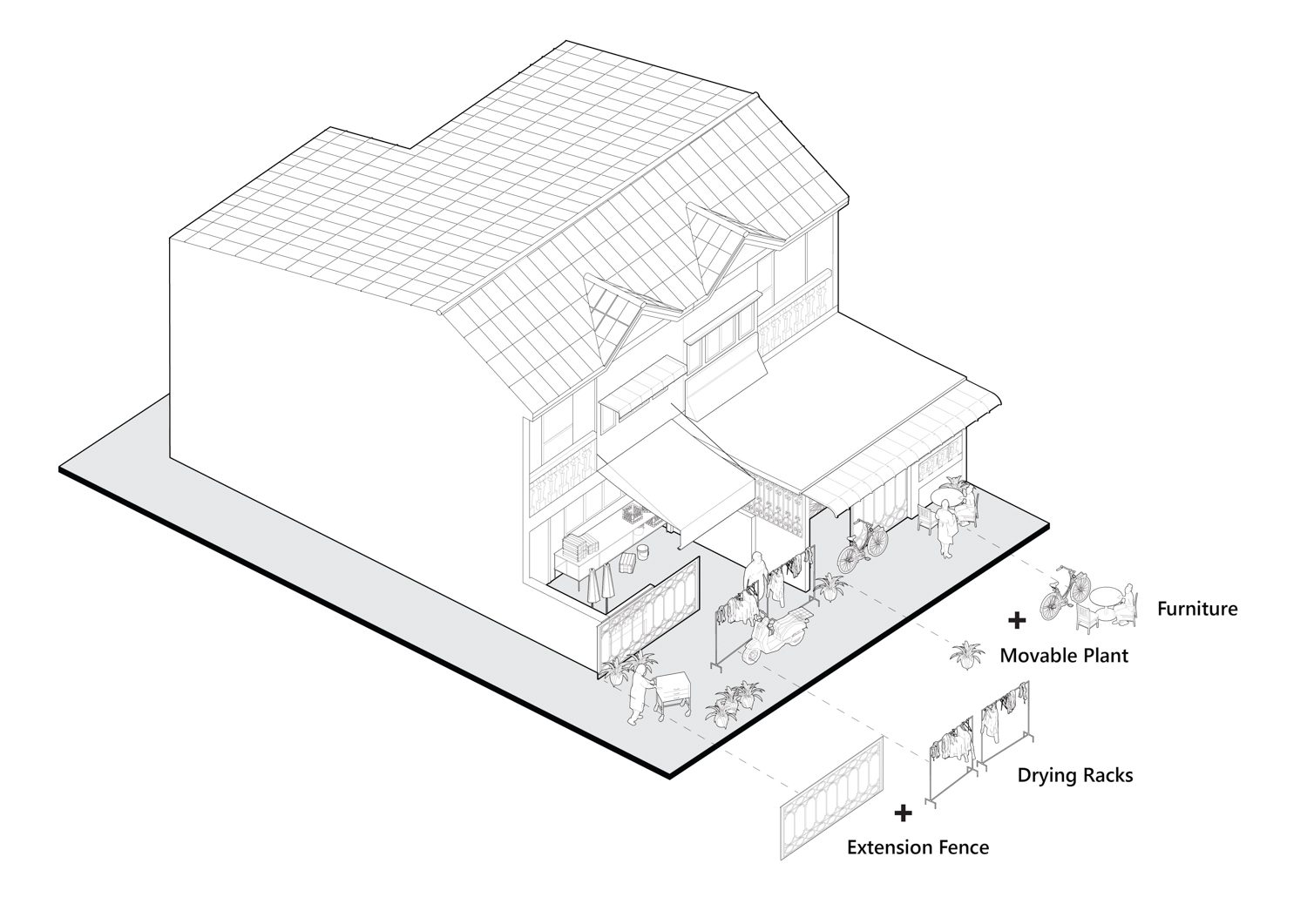

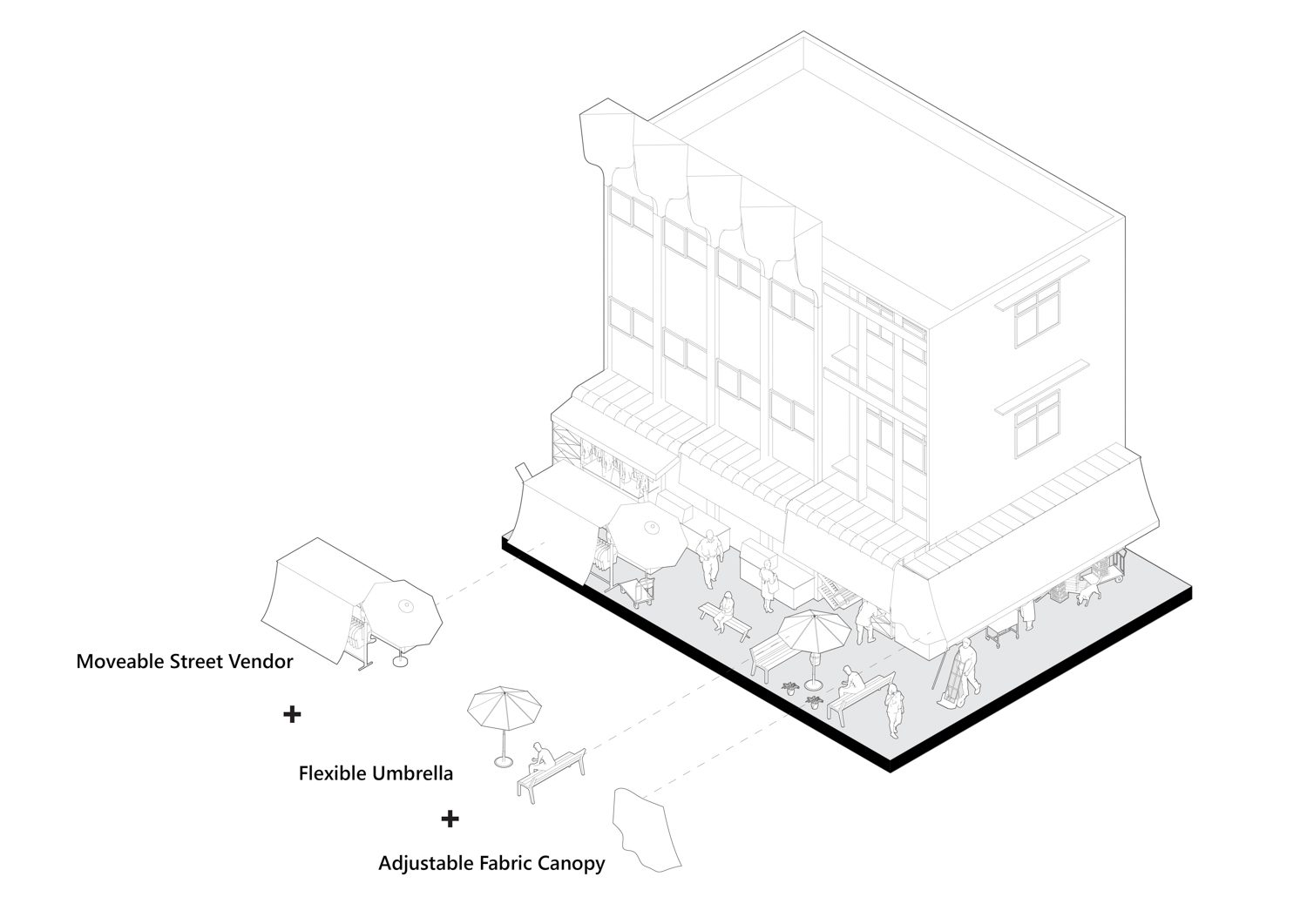

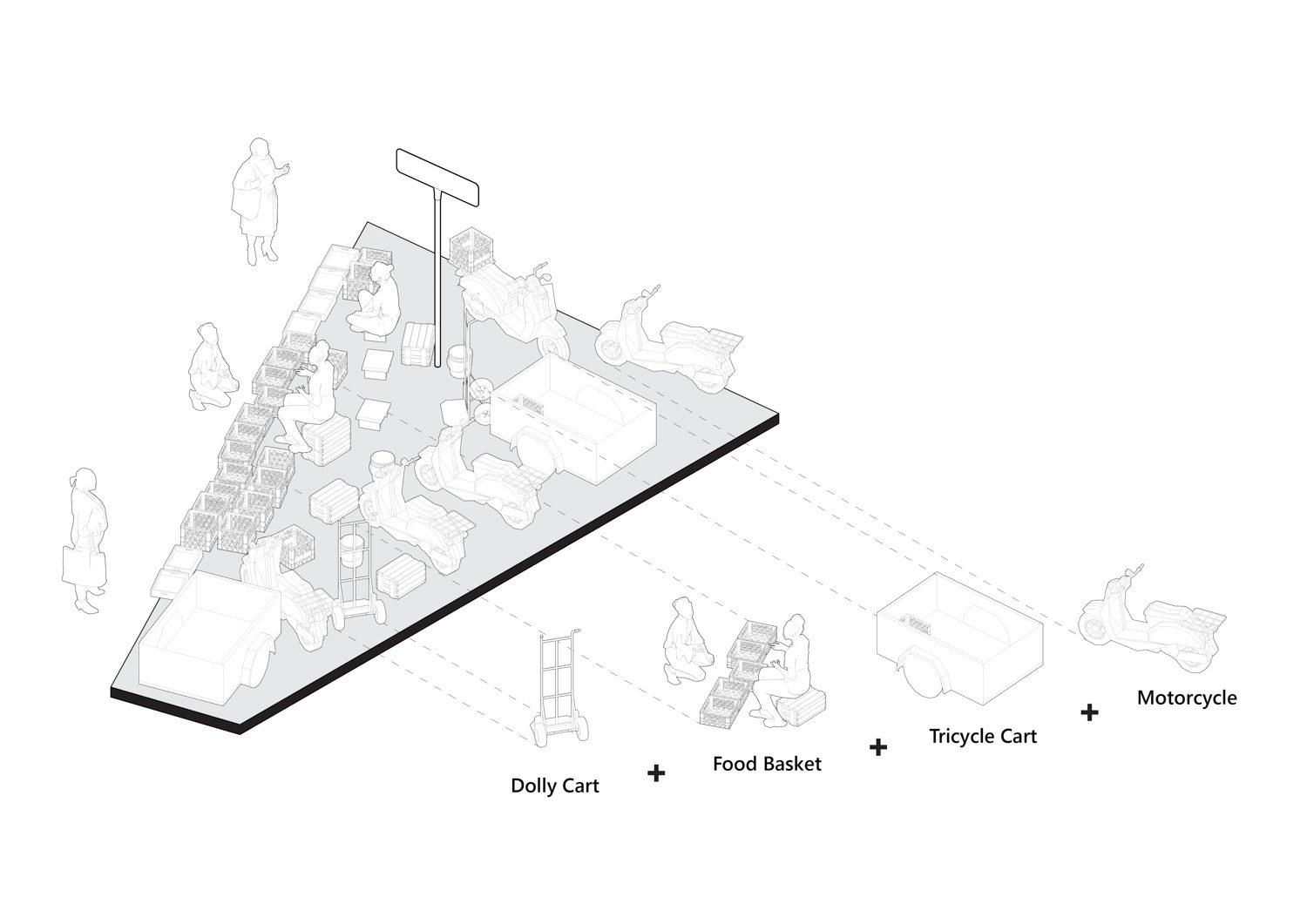

The final principle is Chameleon. If you look at certain streets, for example, in the morning, they might function as markets, with movable stalls that shift throughout the day and night. This is common in many Asian cities, where spaces like shophouses and retail stores can be reconfigured for different functions at different times of the day. It’s much like a chameleon that changes its color to blend in with its surroundings. People, too, adapt to the spaces they inhabit, reshaping them in response to their daily needs and lifestyles. In this sense, cities are dynamic, ever-changing entities, where flexibility and adaptability are essential for the well-being of those who live there.

Shenzhen Gangbianfang Village | Photo: Hung And Songkittipakdee (HAS)

Four years after publishing the book, we’ve come to realize that these concepts—improvisation, manufacturing, and chameleon-like adaptability—are deeply interconnected with sustainability, ecology, and the well-being of the relationship between humans and nature. These three principles form the foundation of our work at HAS Design and Research: how can we design architecture that is holistic, sustainable, ecologically balanced, and conducive to human well-being within the concrete jungles of urban environments?

art4d: You’ve always developed your architectural designs through research. What made you realize that research is such a necessary and important aspect of design?JH: That’s a great question. Personally, I don’t believe in designing within a short timeframe. Architecture is about understanding human life and how buildings will serve their purpose for decades, even centuries. Yet, architects typically spend only a year, or sometimes less, on a design. Naturally, this leads to many oversights. That’s why we devote considerable time to research—to truly understand the context in which a building will exist.

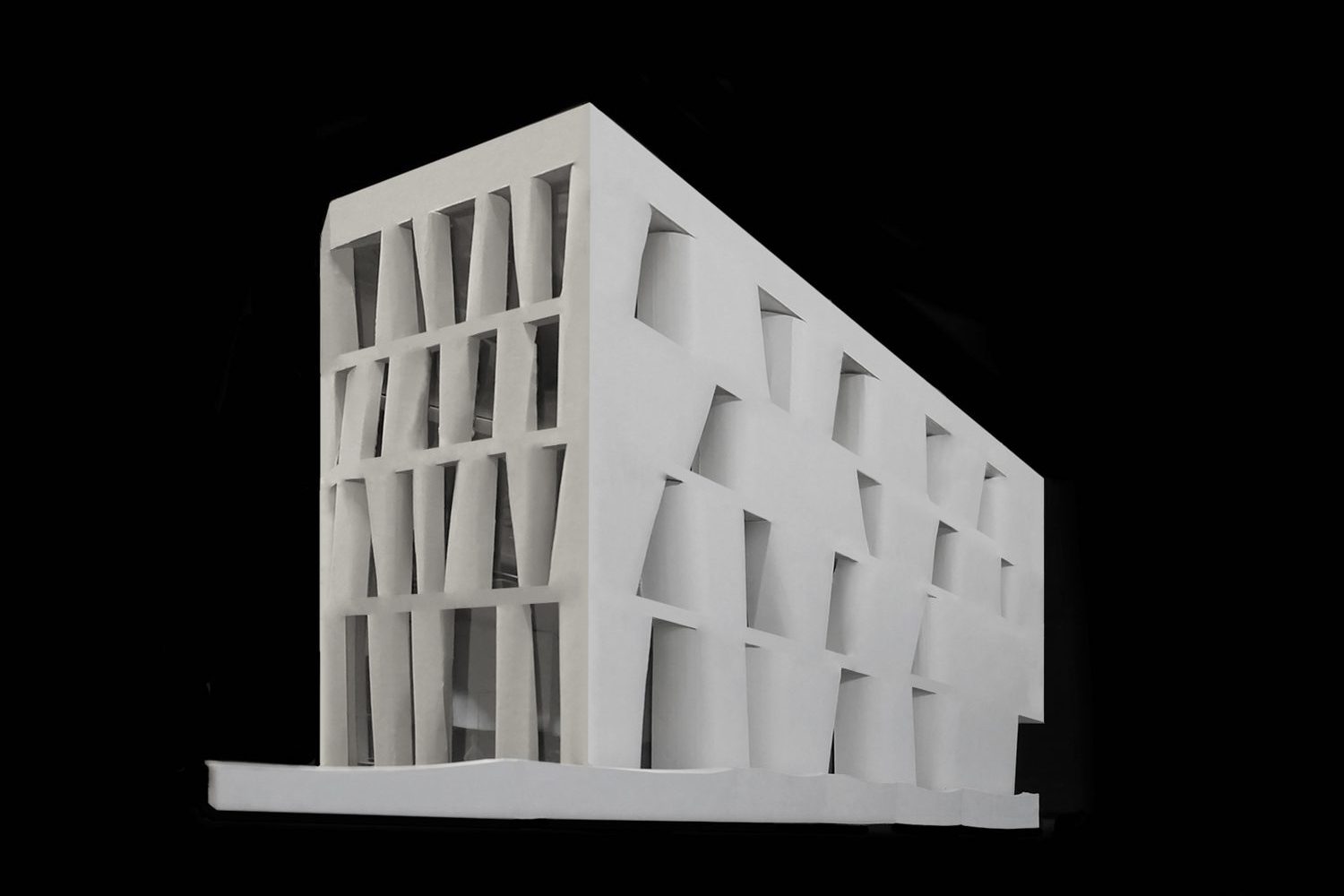

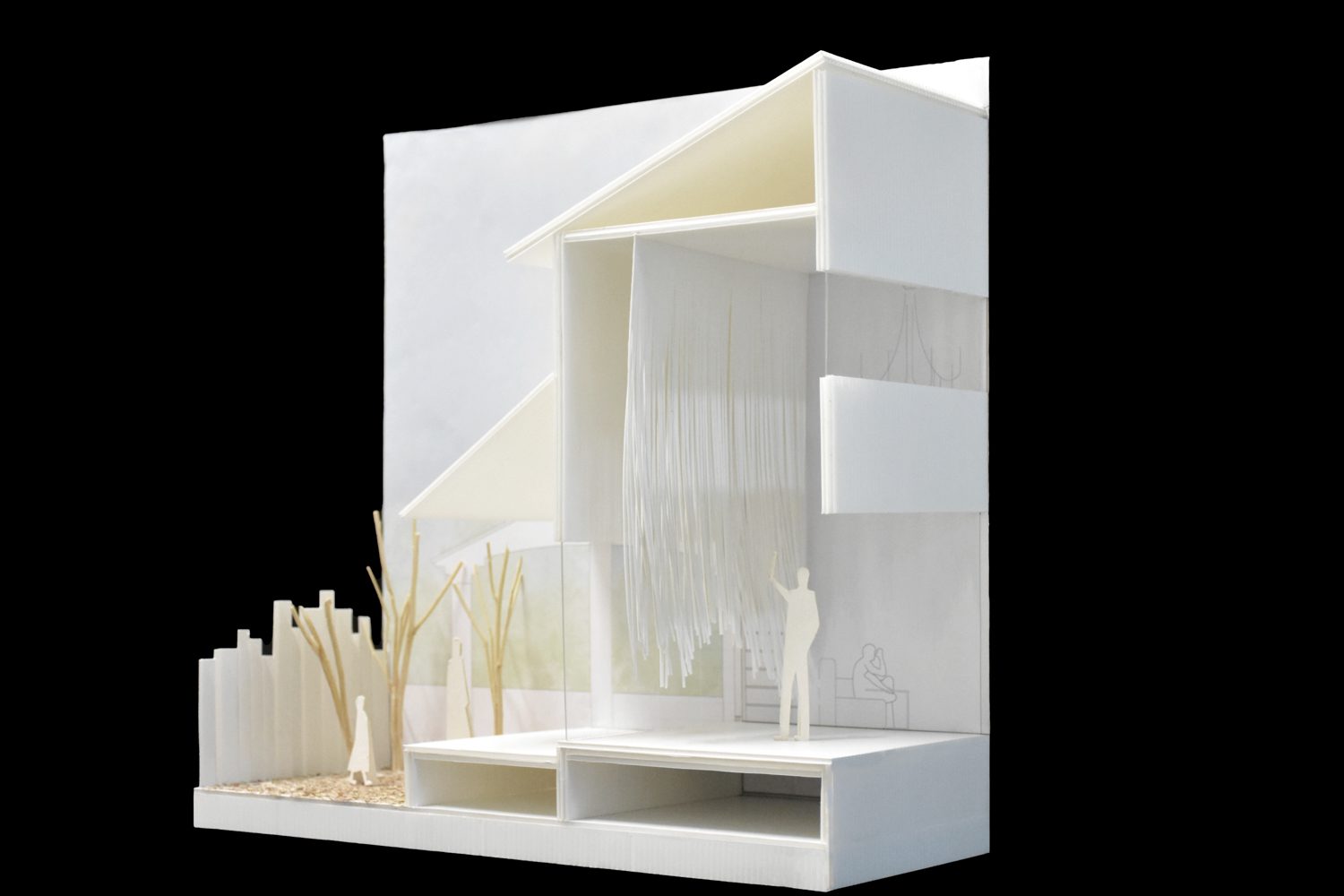

Architectural design of the Simple Art Museum | Photo: HAS design and research

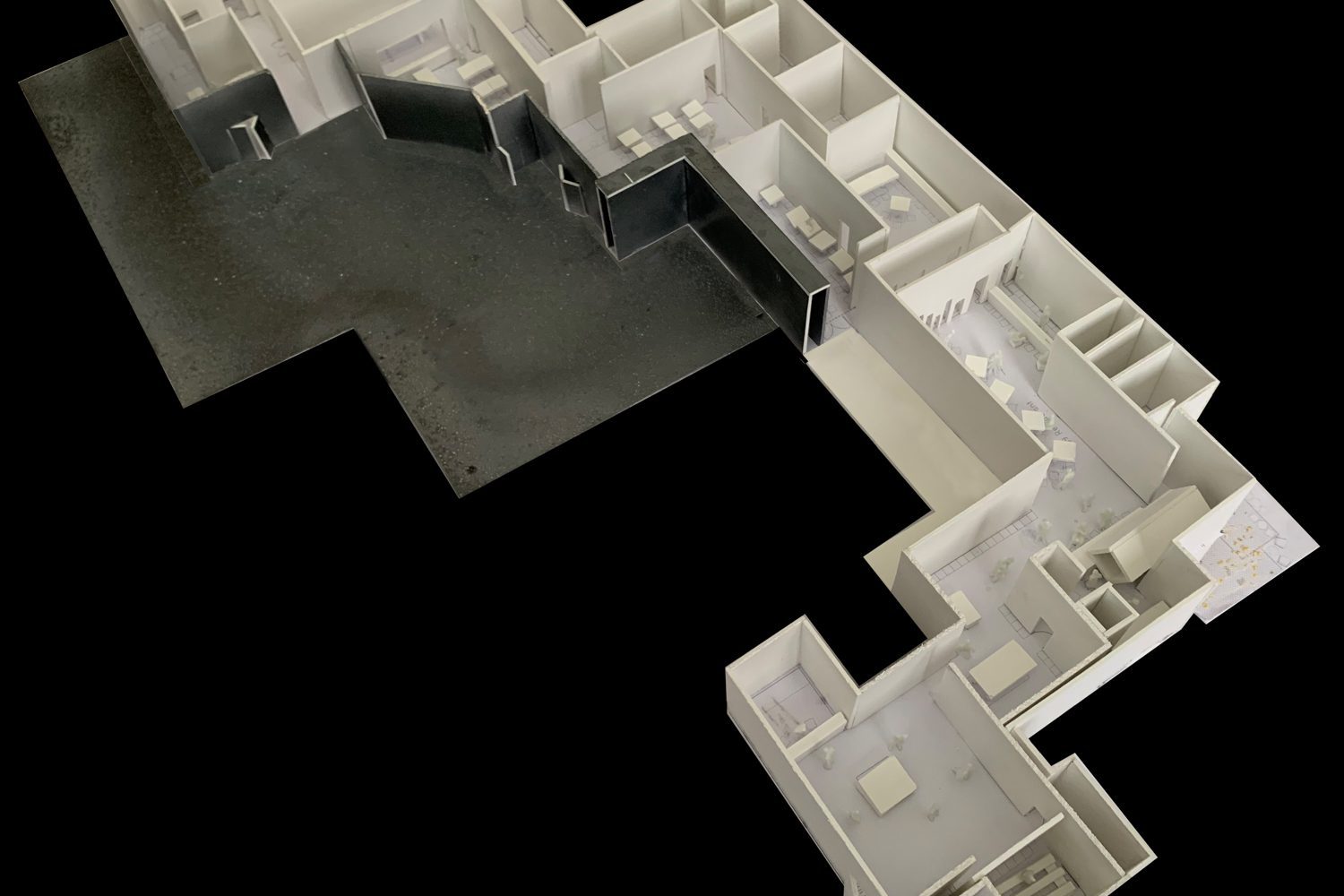

For example, let’s say you’re designing a museum, but you don’t understand the context or the people who will use the space. You need to immerse yourself in the city, observe its environment, and understand the daily lives of its inhabitants. Only then can you grasp how the space will be used. A city is a melting pot of cultures and activities. A museum, for instance, may need to accommodate a variety of functions, meaning the design must be flexible and adaptable.

I also believe that teaching plays a vital role in shaping architectural practice. It forces us to think more deeply about design. When we ask students to approach a project in a certain way, we must be clear about the reasons behind our requests. A semester typically lasts four to five months, which provides more time for reflection than the usual timeframe of a typical project. This time for contemplation is invaluable, and that’s why I have been teaching as a visiting professor at Tongji University and Chulalongkorn University. I dedicate my time to the next generation of students, helping them develop their understanding and approach to architecture.

InJoy Snow Hotel Bangkok | Photo: Panoramic Studio

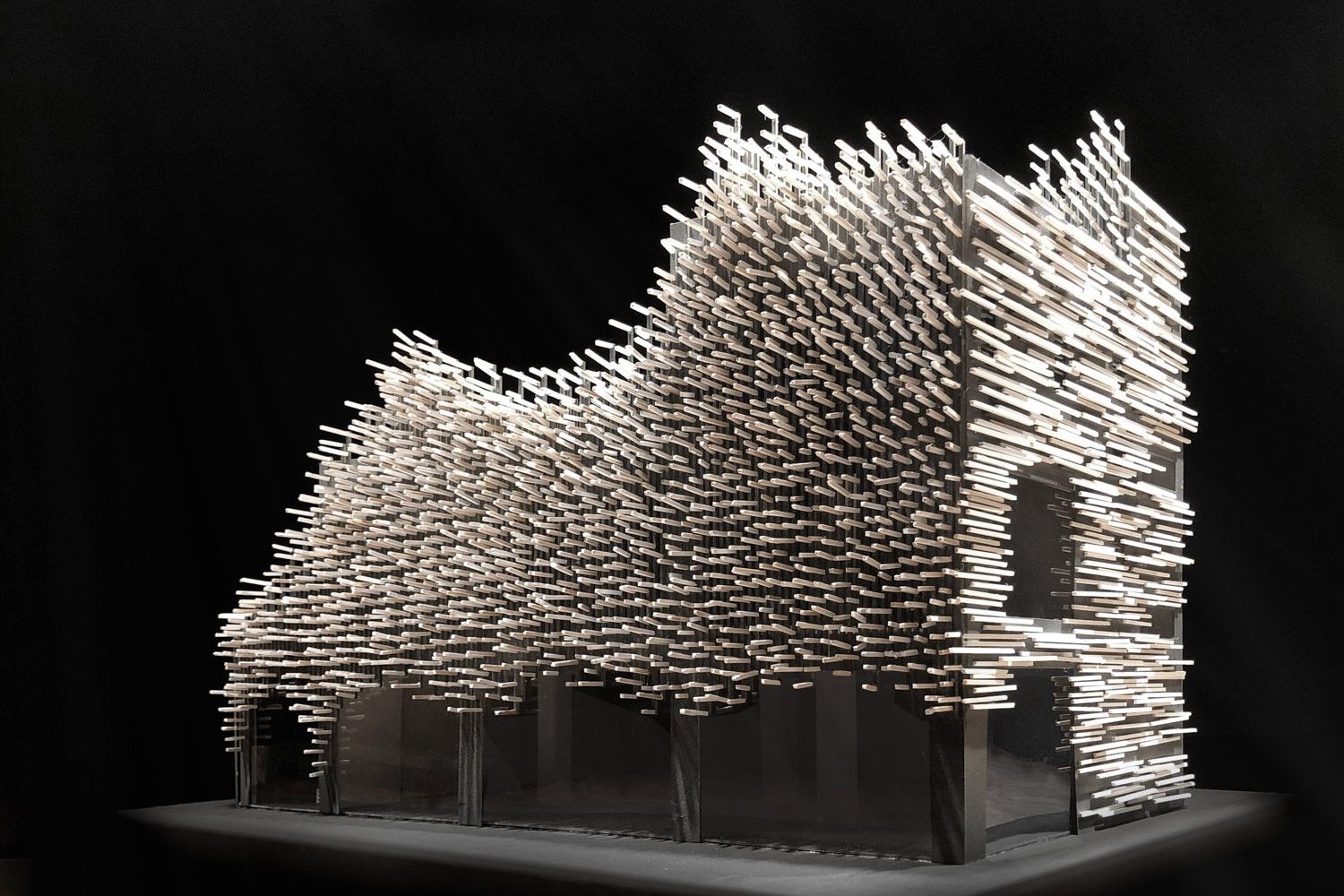

Forest Villa | Photo: Fangfang Tian

Furthermore, I am drawn to architecture that evolves with the seasons, which I think is a crucial aspect of design. To me, architecture is alive. It holds the potential for growth, change, and for evoking personal experiences and emotions that cannot be replicated. Our main goal, therefore, is to create spaces that elicit these experiences and feelings. The exterior appearance of a building is never our primary concern; what matters more is how we craft those experiences and how the architecture evolves over time, rather than focusing on how it looks in the end.

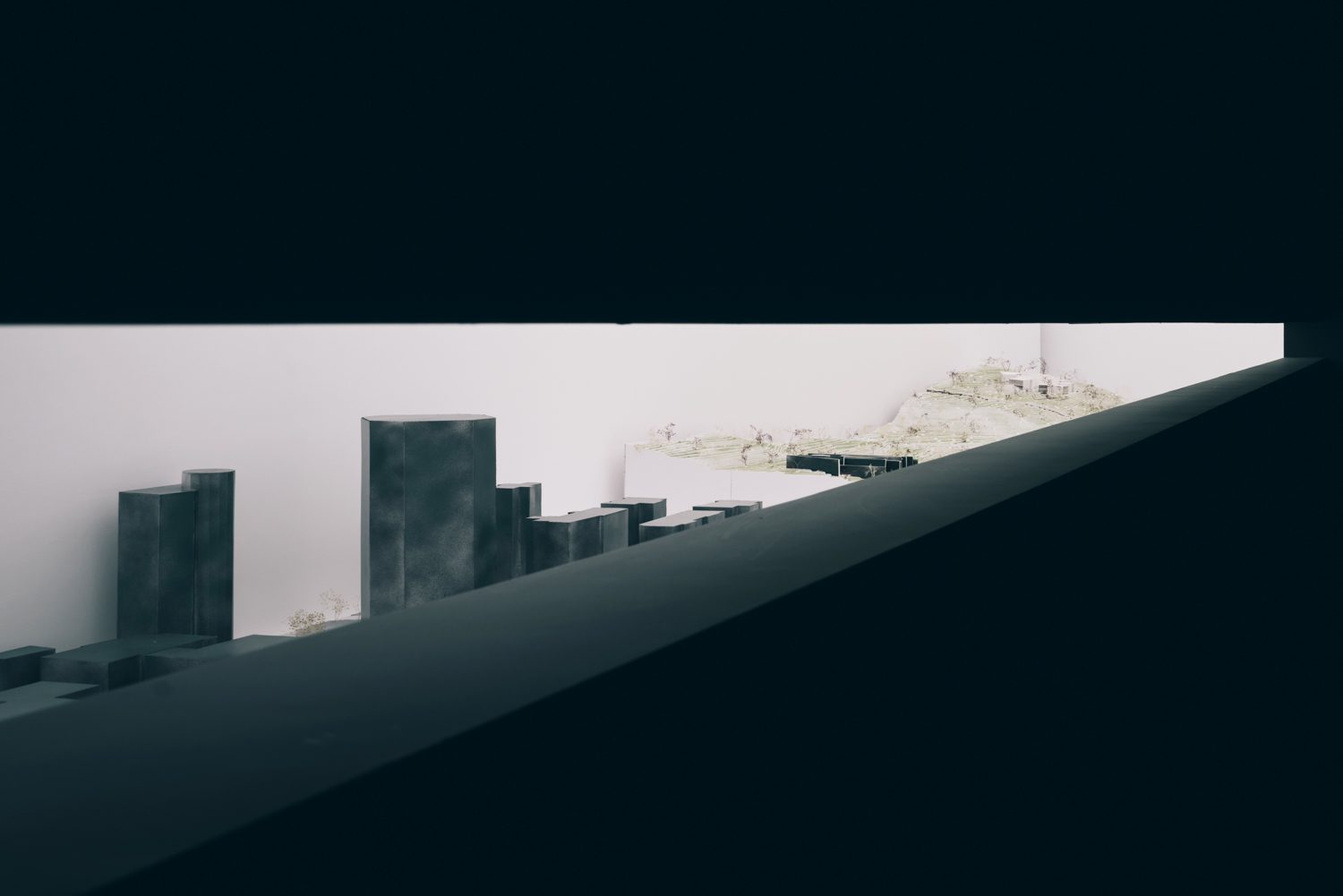

art4d: Can you tell us about some of the research projects you’ve been working on recently?JH: One of the key projects at HAS Design and Research is the Simple Art Museum. We designed and built it nearly three years ago, and it was fully completed this year. The concept of this museum is truly unique. Situated outside a Chinese city, it is not directly connected to the urban fabric. The challenge, then, was to create a new context—one where visitors could find meaning, excitement, and a reason to travel. After all, the museum is located nearly 10 kilometers from the historic city center. Convincing people to make the journey would be difficult unless there was something compelling waiting for them.

Simple Art Museum | Photo: Fangfang Tian

Wat Pho Thong Chedi and Garuda Museum | Photo: HAS design and research

Forest Villa | Photo: Fangfang Tian

Forest Villa | Photo: Fangfang Tian

This kind of space, much like Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp or the works of Louis Kahn and Mies van der Rohe, elicits a profound response. In the case of Forest Villa, this private residence channels a strong energy that resonates with those who enter. When a space is charged with such energy, it inspires action—it excites people. It compels them to take part in shaping the world around them, to contribute to a better life, and to create better cities.

art4d: What experiences did you gain from participating in Guangzhou Design Week 2024, and what are your expectations after receiving the Sustainable Design Award winner?

JH: I want to speak about a broader vision. When we participate in international awards, I believe the award itself is not the most important aspect. What truly matters is the opportunity to encounter brilliant and talented individuals. At these events, we meet many people who ignite our enthusiasm. Designers and architects, each with their own unique approach, present and explain their designs in ways that are both distinctive and inspiring. However, I believe that today, many people place too much focus on the award itself, losing sight of the essence of architecture. We should learn from the past, from figures like Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, and Mies van der Rohe. People admired them not for their accolades but for their architecture and the lasting impact their work had on the world. No one remembers the awards won by Le Corbusier. What mattered was his architecture—the profound effect it had on the world.

In today’s world, I feel the media has shifted the focus. People now pay more attention to the awards than to the work itself. Of course, awards are valuable; they encourage architects to create meaningful projects. But in reality, we should focus on making good architecture, because that’s what truly matters. The award should come as a natural consequence of creating something remarkable. The first question we should ask ourselves is this: How can we create good architecture? If the work is strong, it will be recognized, and eventually, some people or institutions may give you an award. But even if the award doesn’t come, that’s okay. You are still an architect. What matters is that we strive to create good architecture, that we contribute to our communities and improve our cities. It’s not about the award. It’s like a monk who offers blessings and meditation for the benefit of society. They don’t do it for recognition or reward—they do it because it’s their calling. Similarly, architects must continue to create and shape the world, whether or not they receive recognition. The true value lies in the work itself, not in the accolades it may receive.

Jenchieh Hung is discussing the project details in various countries | Photo: Hung And Songkittipakdee (HAS)

Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee believe that architecture is a vision for the future of life | Photo: HAS design and research

art4d: If you had to give advice to young architects in Thailand about working in architecture in Asia or Southeast Asia, what would you recommend?

JH: I’ve learned a great deal from both Japanese and Chinese. As you know, I worked with Kengo Kuma’s firm, and through that experience, I observed how intelligent Japanese architects are. The Japanese have a unique approach to architecture—they are incredibly focused on detail, space, and materials. They are also very tough when it comes to their work. Many work from early morning until midnight. Can you imagine that? Despite their intelligence and toughness, they still dedicate such long hours. They strive to do everything as well as possible. This is what I’ve learned from the Japanese: dedication, attention to detail, and a relentless pursuit of excellence.

From the Chinese, I’ve learned something different. The Chinese are highly active, ambitious, and driven. Many come from cities like Beijing, Shanghai, or Guangzhou. They often go abroad to study and gain experience, and after some time, return to China with big ambitions and a strong desire to contribute to their country’s development. They don’t just want to be the best in China—they want to be the best globally. They are driven by a larger vision, one that seeks to elevate their place in the world. This is what I’ve learned from the Chinese: energy, ambition, and a bold vision for the future.

For young architects and students today, the challenge is tough. Most cities are already built, and there’s only a small percentage of new space left to develop. It’s true—we only have about 10% left to build.

But I would say, first and foremost, aim to do your work as well as the Japanese do. Strive for excellence in everything you create. If you feel you’ve mastered this, then take the second step—aim for a bigger vision, like the Chinese. Think about how you can create something impactful on a global scale.If you feel you’re already at the top in your country, like in Thailand, then look beyond your borders. Consider Southeast Asia, Asia, or even the world. How can you position yourself in this dynamic global environment? When you are young, try to do something unique. Don’t be afraid to stand out and do something different from others. As you grow older, your energy and bravery may diminish. Youth is the time to push boundaries, take risks, and innovate. Lastly, always push yourself to be the best at one thing. Focus on mastering one skill and aim to be the best in the world at it. If you can maintain these three principles—doing your best, aiming for a bigger vision, and striving to be unique—I believe not only will your architectural career flourish, but your entire life will be enriched by the journey.

(Left to right) Jenchieh Hung, Kulthida Songkittipakdee, Founder of HAS design and research | Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Jenchieh Hung | Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Jenchieh Hung | Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan