art4d TAKES YOU TO FIND ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ABOUT WHAT BANGKOK KUNSTHALLE IS DOING, WHY IT IS DOING IT, AND WHO IS DOING IT, THROUGH AN INTERVIEW WITH MARK CHEARAVANONT.

TEXT: KITA THAPANAPHANNITIKUL

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

Not long ago, Bangkok Kunsthalle, Thailand’s newly established art space, came to life within the skeleton of three old buildings once belonging to Thai Wattana Panich, a historic printing house. These buildings, long closed after a devastating fire, had stood as silent witnesses to destruction, their smoke-blackened walls etched with memories that lingered even more deeply than the soot that stained them. Massive columns and beams that once bore the weight of heavy machinery have since taken on a new role: that of living history within an artistic domain. Even the peeling paint, exposing the bricks beneath, lends the space a raw, almost brutal beauty—like crude tattoos marking the passage of time.

For Bangkok Kunsthalle, these remnants are not signs of imperfection, but essential elements of its identity, naturally occurring and worth preserving. Rather than erasing them, the space embraces these scars, restoring and augmenting them to become a backdrop for the ideas explored in its exhibitions. These have ranged from Nine Plus Five Works by Michel Auder and Nostalgia for Unity by Korakrit Arunanondchai, to Mend Piece by Yoko Ono and Calligraphic Abstraction by Tang Chang, among others. Collectively, these projects signal Bangkok Kunsthalle’s quiet emergence as a conceptual art enclave in Thailand—one that gradually poses fundamental questions: What is Bangkok Kunsthalle doing? Why is it doing what it’s doing? And, above all, who is behind it?

art4d sat down with Mark Chearavanont, one of the curators behind Bangkok Kunsthalle, to talk about his background, working methods, personal tastes, and the spirit of rebellion at the heart of his curatorial approach. This rebellious core has, over time, evolved into a central philosophy driving Bangkok Kunsthalle’s work, challenging the present and provoking questions about the future of Thailand’s shifting art landscape.

art4d: What is your background in art?

Mark Chearavanont: I’ve always been interested in art from a young age, especially because of my mother—when I was very young, she ran an art gallery in Hong Kong. So, I was always exposed to art , but I wasn’t necessarily passionate about it until I got older.

When I was younger, I was really into music, and that became my gateway into the art world—not just as a form of creative expression but as a vessel for ideas. That’s something that has always been important to me because I’m most passionate about ideas and the way they take shape in different mediums.

In high school, I started taking photography lessons while attending boarding school in the U.S. Every summer, I spent time in New York, taking photography courses, visiting museums, and exploring the city. That experience exposed me to a lot of interesting art and artists, as well as some of the world’s top museums. At the time, student tickets to MoMA were free, so I would go at least once a week, spending time with the art. I think that experience played a huge role in developing my interest in art in the first place.

At the same time I began taking art history courses at my high school and founded an extra-curricular art club inspired by Jean Michel Basquiat’s street poet alias SAMO.

In college I majored in Art History, which allowed me to really dig into art history and theory while also exploring other academic avenues, such as anthropology, theology, film studies and musicology.

I am interested in the abstract and the ambiguous, impressions and poetics, things that push the bounds of how I perceive reality, feelings that are hard to come by in everyday life.

art4d: How did you step into other forms of art?

MC: Photography was my entry point. The photography courses I took in high school often touched on the history of the medium, which provided context as to how photography exists today and what informed the practice in the past. That was really important for me to understand art within its historical context. Through photography, I was exposed to artists like Man Ray, Robert Frank, or Henri Cartier-Bresson—photographers working in the 1950s and 60s—who were particularly influential. Their work helped develop my passion for visual art as a whole.

art4d: What is the goal of Bangkok Kunsthalle, and why Bangkok?

MC: I come from a fortunate background—I grew up in Hong Kong until I was 14, then went to school and college in the U.S. My dad is Thai, and my mom is Korean, so I’ve been exposed to many different perspectives.

When I first moved to Bangkok, I saw that there was so much room for the local art scene to grow. For me and the rest of the curatorial team, a major reason for starting this project was to help develop and bolster both Thailand’s and Southeast Asia’s art scene. Things are evolving quickly, but artists, curators, and the art world as a whole still need more support. We want to provide that with the resources we have.

A big focus is on elevating local artists—giving artists and art workers more opportunities while also strengthening the overall infrastructure for the art scene here.

art4d: What are the differences between the art scenes in these three countries?

MC: The art scene in Hong Kong is a bit hard for me to recognize because I was very young at the time (laughs). Let’s start with New York. Historically, New York has always been a hub for creatives, so the audience there has a sophisticated understanding of art. When they look at art, they recognize the lineage—what artists are being referenced, what came before.

In Thailand, I think there is less emphasis on art education, and due to limited resources and circumstances, there’s also less exposure to the art world at large. Because of that, the way audiences engage with art is very different. To me, that’s the biggest difference—the way people interact with art in New York versus Bangkok.

In Thailand historically, art has been understood more as aesthetic objects, rather than conceptual expressions, and I think that still influences the way Thai audiences engage with art today. For example, if you go to BACC (Bangkok Art and Culture Centre), there are some cerebral, abstract works in the Biennale, but many visitors are most drawn to pieces that prioritize aesthetics over concept—like Breathing by Choi Jeong Hwa, which features large, colorful vegetables. Of course, this is an overgeneralization, but it’s something I’ve observed.

That’s why, to me, one of the most important aspects of Bangkok Kunsthalle is pushing the way people engage with art—challenging how they think about it. I remember during Korakrit’s exhibition, someone asked me, ศิลปะอยู่ที่ไหน? (Where’s the art?) That was exciting because it meant they were questioning, thinking, and being pushed to engage with something new—something they hadn’t encountered before. And that, in a way, is part of our mission.

art4d: How do you select exhibitions and programs? Do you follow any specific principles?

MC: It goes back to this idea of challenging. When Stefano (the director) and I first put the program together, we had a guiding phrase in mind: Bangkok Kunsthalle is a place for rebels, and I think this is a really important mentality that we’ve carried on into our second year of operation. We have three main criteria. First, the concept— art to think with and to think through, rather than merely to look at. Second, site-specificity—we value work that responds to the space. Third, again, is challenging art—the heart of Bangkok Kunsthalle’s curatorial program.

Every decision regarding the exhibitions and programs selection is always a dialogue. Stefano might propose an artist, and I might question whether it fits. We have discussions to find the right match. We also think more broadly—if we’re showing Richard Nonas, for example, what other works or exhibitions can we include to create a meaningful dialogue? Art is never in isolation; it’s always a conversation, and we want to focus on that.

Another key mission for us is balancing local and international artists. We want to expose Thai audiences to a wider range of artists while also elevating Thai artists by putting them alongside major international figures like Yoko Ono or Richard Nonas, the result is the distinguished dialogue between international and local artists.

Photo courtesy of Bangkok Kunsthalle

Photo courtesy of Bangkok Kunsthalle

art4d: Is there any exhibition that has impressed you the most since the beginning of Bangkok Kunsthalle?

MC: I would say there’s two exhibitions that stick out in mind. The first was ‘nostalgia for unity’ by Korakrit Arunanondchai. Since I’m still relatively new to Thailand, Korakrit’s installation allowed me to understand the local art audience. The show was a hit, garnering around 900 visitors per day and ultimately putting Bangkok Kunsthalle on the map. At the time, I was also working as a docent, so I had the chance to observe how people engaged with the exhibition firsthand. That was really exciting—not just because of the turnout, but because it showed how many people are genuinely interested in art.

The second exhibition is ‘Calligraphic Abstraction’ by Tang Chang, which was the first show that I curated myself. I think I learned so much through the process—I got to put a lot of curatorial ideas that I’ve learned from going to exhibitions, from school, and personal experience. It was incredibly challenging but also deeply rewarding and satisfying. I also felt especially connected to this exhibition on a personal level. Tang Chang was Teochew, and his work was deeply influenced by Chinese philosophy, Taoism, and Buddhism. I’m also Teochew, and I studied Chinese growing up. At university, I was particularly interested in East Asian philosophies, Taoism, and Chan Buddhism, as well as Theravāda Buddhism. Because of this background, I found myself in a qualified position to understand the works of Tang Chang and accordingly convey the singularity and power of his oeuvre to the general public.

art4d: Recently, Thailand has hosted major art festivals like the Thailand Biennale and Bangkok Art Biennale. How do you perceive the changes in Thailand’s contemporary art scene?

MC: I think there’s a significant generation gap in the way people perceive art. The older generation is generally more conservative when it comes to art, favoring eminent Thai painters and more traditional aesthetics. In contrast, inviting artists like Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Korakrit Arunanondchai to the Thailand Biennale is already a bold step forward. It challenges conventions, pushing the whole generation and exposing the younger generation to more global standards of contemporary art.

These visionary artists play a crucial role in putting Thailand on the global art map. Now, we see a growing number of international guests and art enthusiasts from around the world, and this is reflected in our own experience—about 30% of our visitors are foreigners.

One thing I can say though is that there is a lot of emerging Thai talent, for example those represented by galleries like BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY and Nova Contemporary. But again, a lot of these artists either primarily reside outside of Thailand or split their time between living abroad and living here. To me this speaks to a possible lack of artist support or artistic communities. Bangkok Kunsthalle would like to change that.

art4d: Have you had the chance to visit art exhibitions at different venues across Thailand? Is there any recent exhibition that you particularly liked? And why?

MC: I think two exhibitions really stand out to me. The first was Apichatpong’s A Conversation with the Sun, which was part of the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival (BEFF7). It blew me away. Apichatpong is one of the most talented and profound Thai artists working today. Generally, I’m hesitant about art that relies too heavily on technology, but he executed this experience in such a tasteful, subtle, and poetic way. I know an exhibition is impactful when I’m still thinking about it a week or two later, and this one stayed with me.

The second exhibition that impressed me was a specific room at the BACC as part of BAB2024. It featured a Louise Bourgeois work (Janus in Leather Jacket, 1968) installed next to a Yoni sculpture from Lopburi, which is an archaeological fertility device. I learned about this curatorial approach from our curator in residence, Anthony Huberman. He has this concept when curating group shows—’one plus one equals three.’ It’s the idea that when you put two artworks together, it’s not just a combination of those two pieces; something new emerges in the space between them.

My favorite exhibitions are always the ones with a creative curatorial vision at their core. Putting Louise Bourgeois’s work in dialogue with these archaeological objects from the National Museum was beautiful. It created something new because, while art is, of course, a creative expression, curation itself can also be a form of creative expression as well.

art4d: What style of art is your favorite and why?

MC: I think what really got me interested in art in the first place, and this goes back to when I was a teenager in New York was modernism—particularly the Impressionists like Henri Matisse and Edouard Manet. Looking at it now, it may not seem as avant-garde, but at the time, it was pushing the boundaries of what art could be. I’m also fascinated by modern artists who worked with conceptual ideas, such as Yves Klein and Marcel Duchamp. They’ve deeply influenced my own artistic practice and curatorial practice.Actually in college, I focused on Buddhist art because I was intrigued by the intersection of religion, theology, and art. One of my favorite projects was writing a paper on Wat Phra Kaew, analyzing the political context of its murals and how they combined royal imagery with Jataka tales—the life story of the Buddha

However, I’d say music and film are still my biggest passions. That’s why we were really pushing for a film program, which now we’ve created, then the music program is the next thing we want to explore.

art4d: Why music and film?

MC: Music and film are incredibly accessible art forms. It requires a lot less historical and cultural context to appreciate a song or film. That’s really important to us at Bangkok Kunsthalle. We want to be inclusive, not exclusive. We want to create a space that’s not intimidating but open to everyone. Stefano and I envision Bangkok Kunsthalle as a public square, a space for all creatives—filmmakers, musicians, and artists alike—to come together and share ideas. I think a big part is also not just to show art. it’s about creating discussions, creating social spaces for artists, for creatives, for curators, for art workers and all adjacent communities.

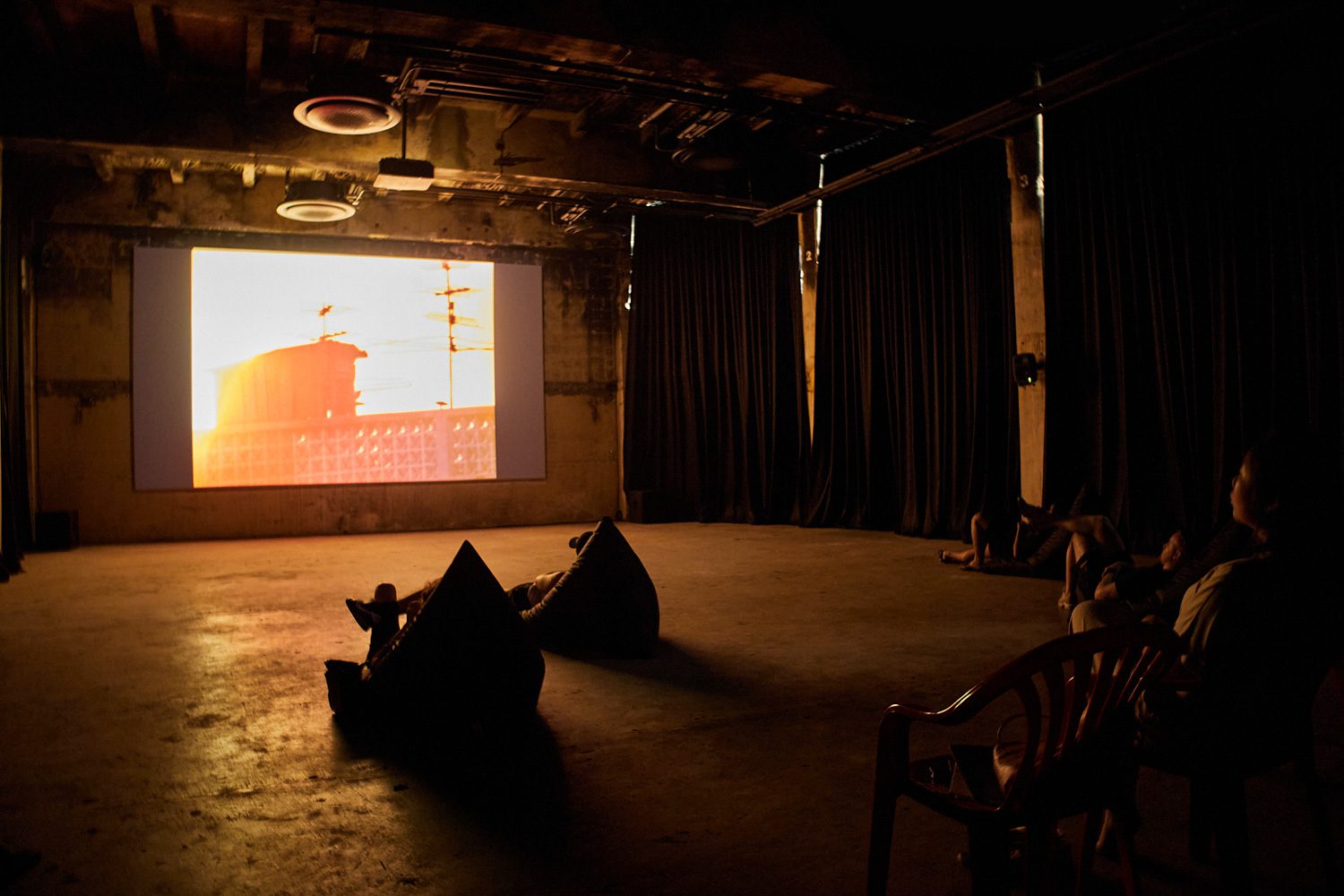

art4d: Do you have any plans to further develop this space beyond the gallery?

MC: Our approach at Bangkok Kunsthalle is to stay flexible and adapt to the needs of artists and exhibitions. For example, the film program upstairs was initially curated by a guest curator Komtouch ‘Dew’ Napattaloong, but we wanted to keep the space active, so we plan to continue using both as a screening space, but also as a multifunction space for gathering. Looking ahead, we’re considering ideas like an open-air cinema, spaces for artist residencies and studios, and even inviting commercial galleries to have a presence here.

art4d: How do you experience working with artists as a curator?

MC: Some artists come in with a fully developed idea and exhibition layout—they know exactly what they want. Our artists in residency on the other hand, spend time immersing themselves in the city and drawing inspiration from their experiences in Thailand. The idea and the final result blooms during their time with us. In other cases, we work with the artist’s estate, which means the curatorial process is leans much more heavily on the curatorial team.

For example, when curating Tang Chang, I had to go through his digital archive, which contained almost 3,000 works. I spent about two full weeks selecting, refining, and revising which pieces to include. That process was both fun and challenging because I wanted to find novel ways of presenting and programming the artist’s rich body of work.

What I enjoy most about this job is working directly with artists. For our first show, Nine Plus Five Works, with video artist Michel Auder, I spent a month exploring Bangkok through his perspective. It even changed how I saw the city, and made me appreciate it more. Conversations with artists often spark curatorial ideas, and to truly curate their work, you have to get into their mindset and understand their process.

art4d: In your opinion, how can Thailand’s contemporary art scene be enhanced to meet international standards?

MC: I feel that one of the main factors hindering the development of the art scene here is art education and exposure. Many fundamental frameworks for understanding art are still missing—not just from the perspective of art historians and curators, but also for the general Thai audience. It ultimately comes down to exposure. I believe there needs to be greater exposure—not to any specific style, but to a wide diversity of artistic practices—to inform both the practice and consumption of art locally.

Another important factor is the need for better infrastructure, whether through private or public funding, more career opportunities in the arts, or affordable spaces where young artists can exhibit their work. That’s also what we’re trying to do—offering open calls and workshops. For example, we’re in collaboration with YOONGLAI COLLECTIVE, a Thai curatorial collective, as well as a group of Silpakorn University students who we’ve invited to put on their own exhibition in the space.

art4d: Thailand already has prominent art spaces, for example like BACC and Jim Thompson. How does Bangkok Kunsthalle contribute to and complement the country’s art scene?

MC: Most art spaces in Thailand follow the ‘white cube’ model, which strips away context to focus entirely on the artwork itself. Our approach is completely different. We don’t even want to clean or scrub the walls—we want to keep the space as raw as possible. That’s because all art exists in dialogue with its surroundings, both historically and physically. Instead of neutralizing the space, we carefully select artists who can and are eager to engage with it, react to it, and truly interact with the space.

For example, when Korakrit first visited our space, we gave him complete freedom to choose any location in the building for his installation. He selected a specific space because, as he put it, it felt like a dystopian church. Without that space, the exhibition wouldn’t have happened the way it did, and it wouldn’t have been as successful. It’s the context that provides another level of understanding of the art.

art4d: What is the main characteristic of Bangkok Kunsthalle that impacts the exhibition and the artists in physical terms?

MC: I think there are two key factors. First, the layout of the buildings plays a big role. We have what we call Building B and Building C. Both of these were originally warehouse spaces, so they offer open, neutral areas with no built-in furniture. This makes them ideal for art exhibitions because the space is versatile and easy for artists to work with. Building A, on the other hand, was originally the front office of the printing company. The space is characterized by columns that extend through the four floors, almost like concrete trees creating an urban forest.

Second, the history and character of the buildings themselves are important. It was built in 1952, is 75 years old, and its natural character is very clear. It has its own history and story, which many artists want to reference and play with.

For example, when we showed Tang Chang’s work, I focused on calligraphy because it’s references the history of the building as a place for text, for writing, for language, so even as a curator, I always try to keep in mind the history of the building.