KASUMIGAURA LAKE COMMUNITY PLACE IS A PROJECT TO REVITALIZE AN OLD LAKESIDE PUBLIC BUILDING THROUGH A NEW DESIGN BY TAKAHASHI IPPEI THAT INTEGRATES NATURE, ANIMALS, AND PEOPLE INTO A SINGLE SPACE

TEXT: KARN PONKIRD

PHOTO: ©︎TAKAHASHI IPPEI OFFICE

(For Thai, press here)

When Kasumigaura Fureai Land, a long-standing complex comprising a science museum, observatory, and water park on the shores of Lake Kasumigaura in Ibaraki Prefecture, first opened in 1992, it operated for many years before eventually closing. Architect Takahashi Ippei of TAKAHASHI IPPEI OFFICE was commissioned to design a new zoo that would emerge from the restoration of the existing architecture. The brief called for a space that could accommodate new functions while retaining the structure and outline of the original buildings to minimize construction costs. At the same time, the project sought to offer visitors an engaging, up-close experience with animals, within an environment that allows each species to adapt and live comfortably.

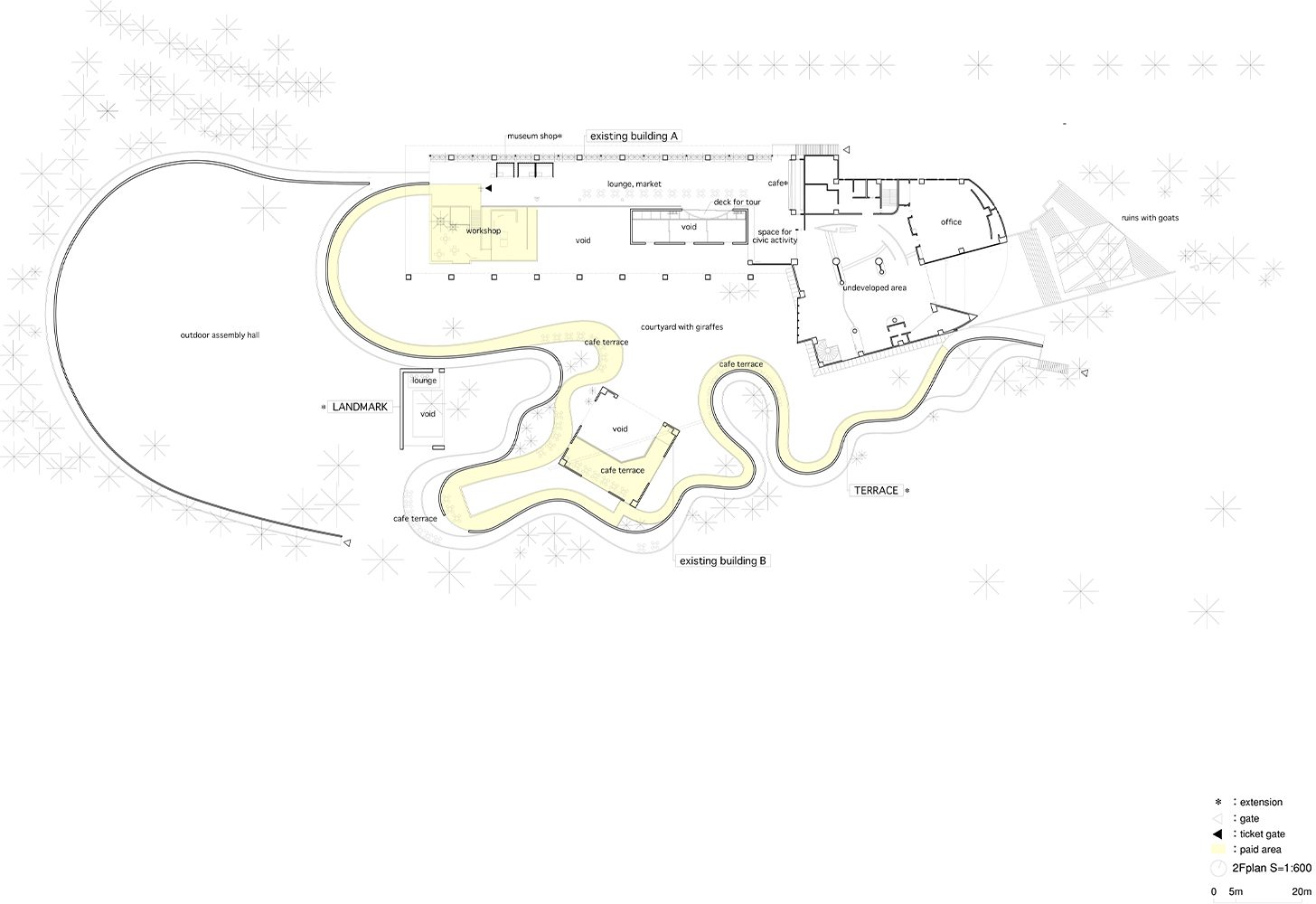

The resulting project, Kasumigaura Lake Community Place, transforms the former public facility into a combined zoo, museum, and community multipurpose space, encompassing a total floor area of 4,968 square meters on a site of approximately two hectares.

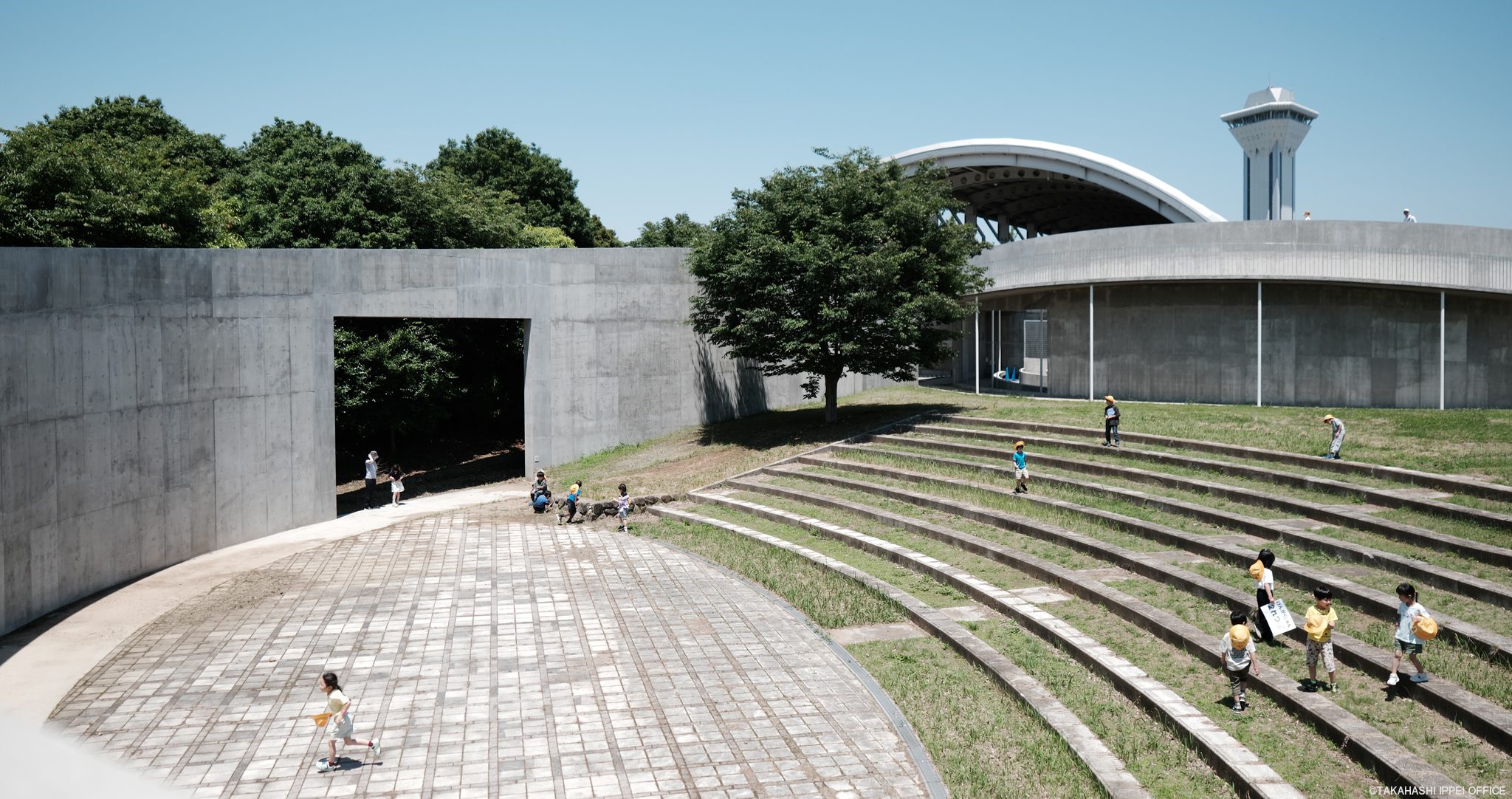

Takahashi Ippei designed a winding concrete walkway that wraps around the existing buildings, which consist mainly of steel structures with portions of reinforced concrete. All former interior functions were removed, leaving only the essential framework, roof, and structural frame. The building’s generous height and double-volume spaces were repurposed to provide shaded areas where large animals such as giraffes can rest. These spaces also serve as venues for feeding activities, allowing visitors to interact with the animals in close proximity. The second-floor balcony has been converted into an open-air café and lounge, offering visitors a place to relax and dine while maintaining eye-level contact with the giraffes.

The spatial layout was reorganized to establish a clear hierarchy of interaction between humans and animals. Takahashi defined five gradations of space, moving from the most open to the most enclosed: open outdoor space, outdoor space with boundaries, covered outdoor area, semi-outdoor interior without air conditioning, and air-conditioned interior space. These zones are linked by a newly designed walkway that serves both as circulation and as an enclosure to prevent animals from leaving the grounds. It also guides visitors through a continuous sequence of spaces that gradually shift the level of intimacy and engagement with the animals.

The ‘natural condition’ of Kasumigaura Lake Community Place, as conceived by Takahashi, differs from the conventional approach of replicating the animals’ original habitats within a zoo. Instead, it reflects a perspective in which human-made architecture, once transformed and adapted, gives rise to a new environment that animals can inhabit by tracing and continuing the spatial traces left behind by humans.

The outdoor activity plaza, for instance, serves not only as a venue for festivals and gatherings but also as a grassy field for animal keeping and pony-riding activities for children. The staircase of the former building has been repurposed into a climbing terrain for hoofed animals such as goats and alpacas. The steps and concrete beams were deliberately roughened, their surfaces chipped away to create a coarse texture that allows the animals’ hooves to grip and move safely across.

Although Kasumigaura Lake Community Place has only recently opened, and time will tell how well its spaces truly serve both people and animals, the project already stands as an example of effective collaboration between the public and private sectors. It demonstrates how disused architecture can be meaningfully revived through a transparent and well-coordinated process. The local government took the initiative to develop a rehabilitation plan and conduct an open bidding process to select private partners, while a consortium of companies assumed responsibility for different aspects of the project’s operation and management. Together, these efforts present an inspiring model for how architecture can gain new life and purpose without resorting to demolition.