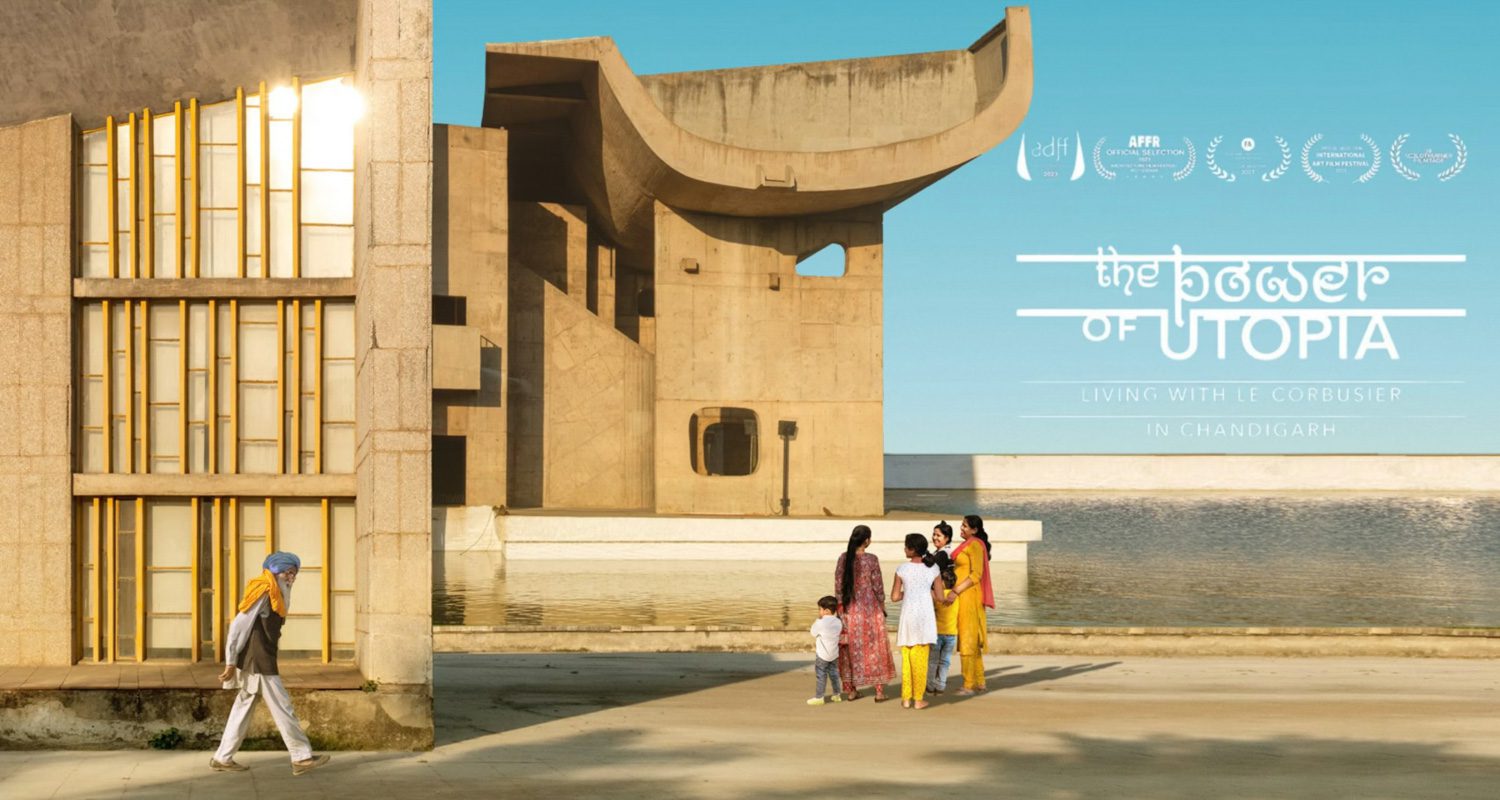

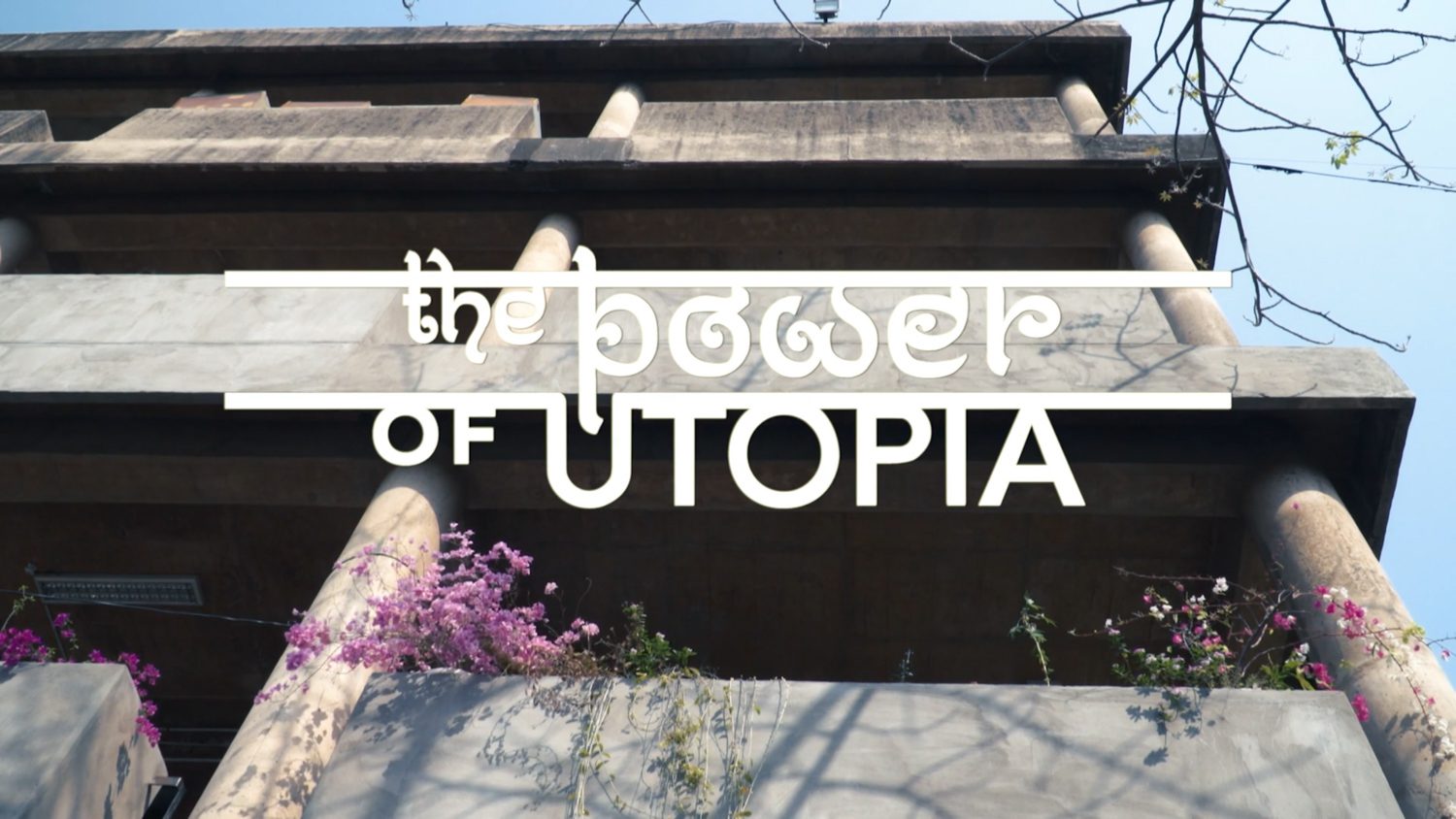

THE POWER OF UTOPIA, A DOCUMENTARY THAT LOOKS AT LE CORBUSIER’S WORK THROUGH THE EYES OF ITS INHABITANTS, OPENS UP A SPACE FOR DIALOGUE BETWEEN ARCHITECTURAL THEORY AND REAL-WORLD URBAN PRACTICE

TEXT: XAROJ PHRAWONG

IMAGE COURTESY OF KARRER MULTIVISION

(For Thai, press here)

Modern architecture has long been cast as the antagonist of the twentieth century by architectural scholars. Brent C. Brolin’s The Failure of Modern Architecture famously confronts the blind spots of the movement, critiquing the top-down approaches that shaped many of its most ambitious projects. Among his examples of modernism’s overreach is Chandigarh, India, a city often cited as a case where European modernist ideals were imposed wholesale onto an Asian context.

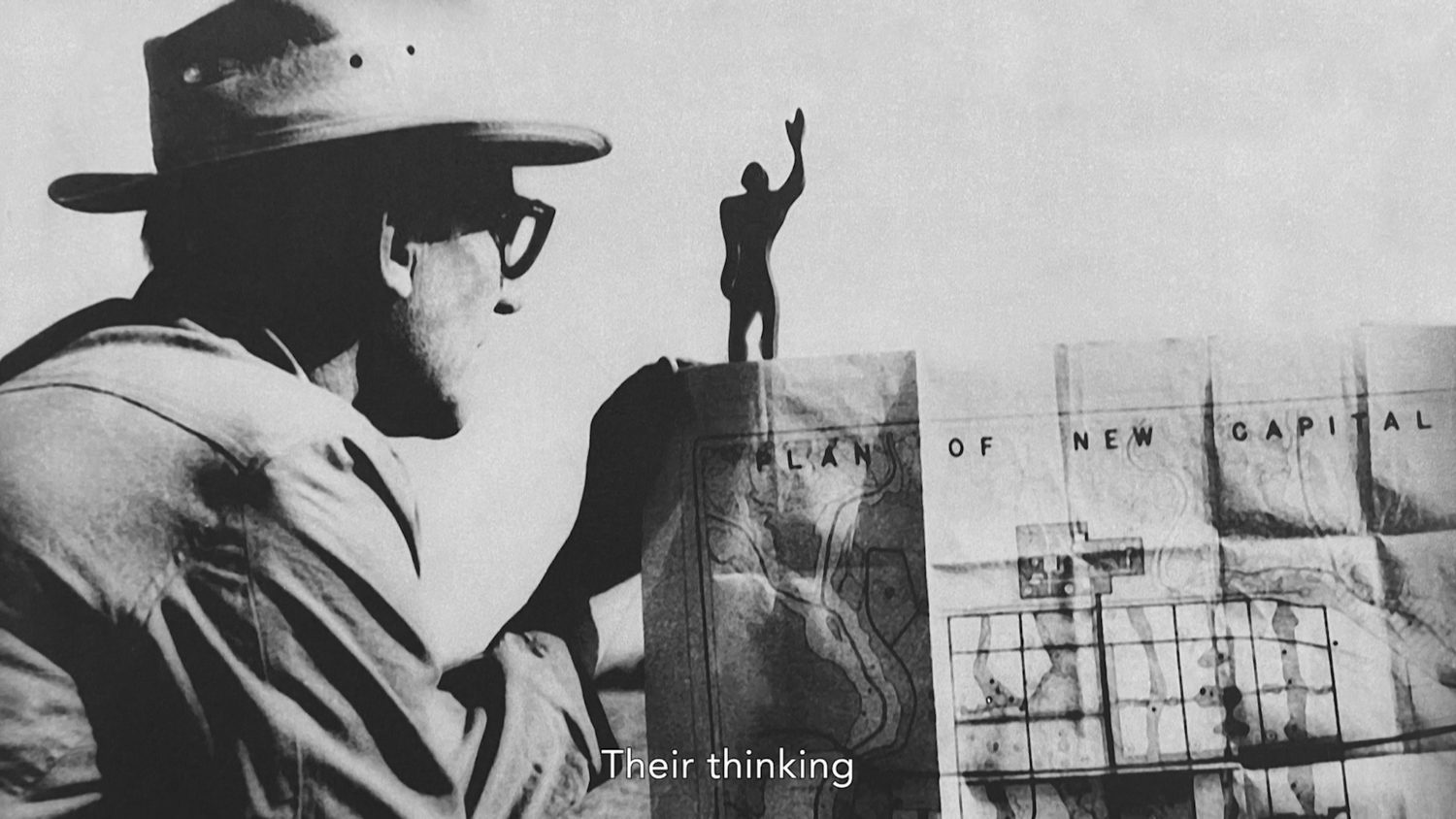

The story of Chandigarh begins in the tumultuous years following the partition of Pakistan from India after independence from the United Kingdom. One of the challenges that emerged in the wake of this event concerned the state of Punjab and the need to establish its new capital. In 1947, India’s Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, turned to one of the most influential architects of the century, Le Corbusier, entrusting him with the vision for a new capital city. For Corbusier, it was the opportunity he had tirelessly pursued, after years spent traveling across Europe to present his radical urban schemes, and even undertaking seven wartime trips to Algiers in an effort to advance his ideas. Although those proposals were repeatedly set aside, the modernist dream he championed finally took shape in Chandigarh.

From the story of Chandigarh, Le Corbusier’s idealized capital city is reexamined through the lens of two Swiss filmmakers, Karin Bucher and Thomas Karrer, in their documentary The Power of Utopia.

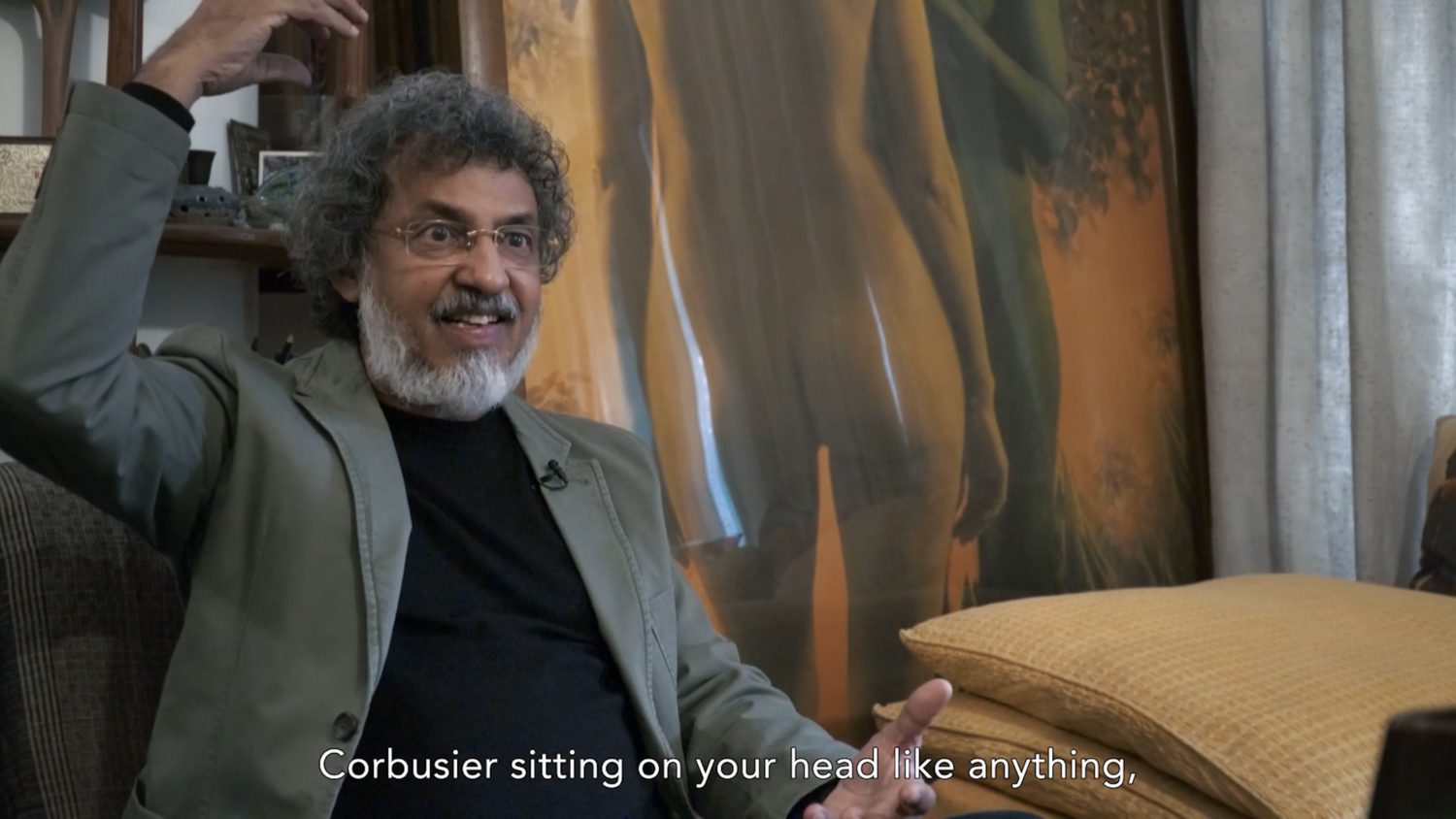

The film opens quietly, with a series of interviews featuring the city’s residents: people from varied professions and backgrounds, each reflecting on the advantages of this modern city that has served the people of Punjab for more than seventy years. Their voices are interwoven with insights from architect and scholar Deepika Gandhi, an alumna of the Chandigarh College of Architecture, a renowned institution founded in an environment profoundly shaped by Corbusier’s ideas. Gandhi’s account sheds light on how the city was conceived as a model for improving everyday life, a claim she evaluates through her own lived experience, first as an architecture student navigating the city, and later as a professional who continued to inhabit it. Her perspective stands in contrast to those of many scholars outside India, whose critiques of Chandigarh often diverge sharply from the experiences of the people who call the city home.

The documentary then shifts to conversations with street comedians whose performances takes place freely in Chandigarh’s public spaces. These open plazas allow them to practice their craft without restriction, drawing crowds who gather around them and naturally interact within the urban commons. Through their performances, these comedians are able to communicate their messages, something far more difficult in many other Indian cities where well-designed public space is scarce.

Chandigarh, in this sense, represents Corbusier’s utopian city in its purest form. The radical ideas he once presented across the world, and which were repeatedly rejected, finally took tangible shape here. It is hardly an exaggeration when one interviewee remarks that living in Chandigarh means one cannot escape Corbusier: sitting, sleeping, standing, eating. Daily life unfolds as if lived inside the architect’s mind. One performer describes the city as a place for ‘new, modern minds.’ In other parts of India, he explains, it is socially unacceptable for couples to walk hand in hand in public. In Chandigarh, however, such everyday acts are entirely unremarkable.

The documentary also turns its gaze toward the early housing blocks built during the city’s founding. These government-designed dwellings are still in use, and residents express genuine satisfaction with the homes they inhabit. Both through the film’s lens and through the author’s own experience, the city appears noticeably cleaner and more orderly than any other Indian city previously visited.

In its closing moments, the documentary captures scenes of schoolchildren moving freely between the blocks of each sector, crossing from one to another without fear of cars intruding into their paths. This imagery recalls Le Corbusier’s concept of the 7Vs, a hierarchical system of circulation that organizes Chandigarh’s mobility infrastructure across seven distinct levels:

V1 – arterial roads, the primary arteries that connect Chandigarh to neighboring cities

V2 – major boulevards, secondary main roads

V3 – sector definers, streets that delineate the city’s sectors

V4 – shopping streets, commercial routes

V5 – neighborhood streets, residential streets

V6 – access lanes, routes leading into specific destinations such as individual homes

V7 – pedestrian paths, walkways dedicated solely to people on foot

In later years, Corbusier added an eighth category, V8: cycle tracks, expanding the system to include dedicated routes for bicycles.

Throughout the documentary, the filmmakers emphasize the quality of Chandigarh’s public spaces, noticing how they far surpass those found in most Indian cities. These settings accommodate a spectrum of activities, from street performances and casual cultural gatherings to relaxed outdoor exercise. The film’s depiction of such everyday scenes reinforces its interpretation of ‘utopia,’ a term that here opens itself to multiple meanings: a paradise, an ideal society, or even a vision of a future world.

Ultimately, the documentary serves as a work that speaks in defense of modern architecture in India, countering earlier publications that have long cast it in a negative light.