THE COMMUNITY-BASED DESIGNER WHO BELIEVES THAT DESIGNER’S ROLE IS NOT LIMITED TO DESIGNING BEAUTIFUL ARTWORK

TEXT: PIYAPONG BHUMICHITRA / NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

PORTRAIT: KETSIREE WONGWAN

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

“I quit my day job working at a magazine with the feeling of wanting to spend a couple of months living in the woods.”

What was the reason behind the urge that drove Techit Jiropaskosol to leave his job in pursuit of something when we first heard his recollection, could it be from watching the film Into the Wild? We weren’t exactly sure. He then clarifies our curiosity, telling us that it was actually an anti-capitalism read that sprung the idea of living a jobless life for a change. Referring to himself as a ‘facilitator,’ Jiropaskosol is now working as a part of the SATARANA network and known to many as Trawell or MAYDAY.

The facilitator began his first paying job working as a graphic designer for a clothing company called Parawindsor. He wasn’t a properly trained in graphic design, but a graduate from the English Department of the Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University with a barely-made-it GPA score.

Photo courtesy of MAYDAY / Suwicha Pitakkanchanakul

“The first year was like my very own graphic design school. I learnt how to use programs, dealing with the market, the clients, the production and advertising aspect of the business. An AE from You are Here magazine came to our office one day. I read the magazine, absolutely loved it and decided to apply for a job there.” After two years working at the magazine, You are Here closed down and Jiropaskosol landed himself a job at Michael Paul Young’s YouWorkForThem. He recalls the experience being a very free working environment where his boss would recommend the books that would go with the style he was working on and encouraged him to experiment on things he wanted to do.

Our initial interest to sit down and talk with Jiropaskosol might have been from his Facebook name that got us confused at first thinking that he was some Japanese dude who can write Thai, the contents of the social media statuses which were criticizing the ways of the world, the photographs he posted. Whatever the reasons may be, we believed that there had to be something good coming out from our conversation. We might get to know him a little bit better, and understand more about what molded him into the person he is today. He is a graphic designer who hasn’t been academically trained in graphic design, working in a commercial sector before entering the realm of volunteer work. What is it exactly that still makes him continue to walk on this path? It would probably be something we would never entirely wrap our head around, but we are all here to listen to what he had to say. So, our talk continued.

“After a while, I wanted to leave YouWorkForThem because I had a plan to pursue my studies. But one thing led to another and I ended up working as a motion graphic designer for B-floor, and did a show in New York. I later had this realization that I wanted to do more for others, and that I wouldn’t live a life making a name for myself without contributing anything for others.”

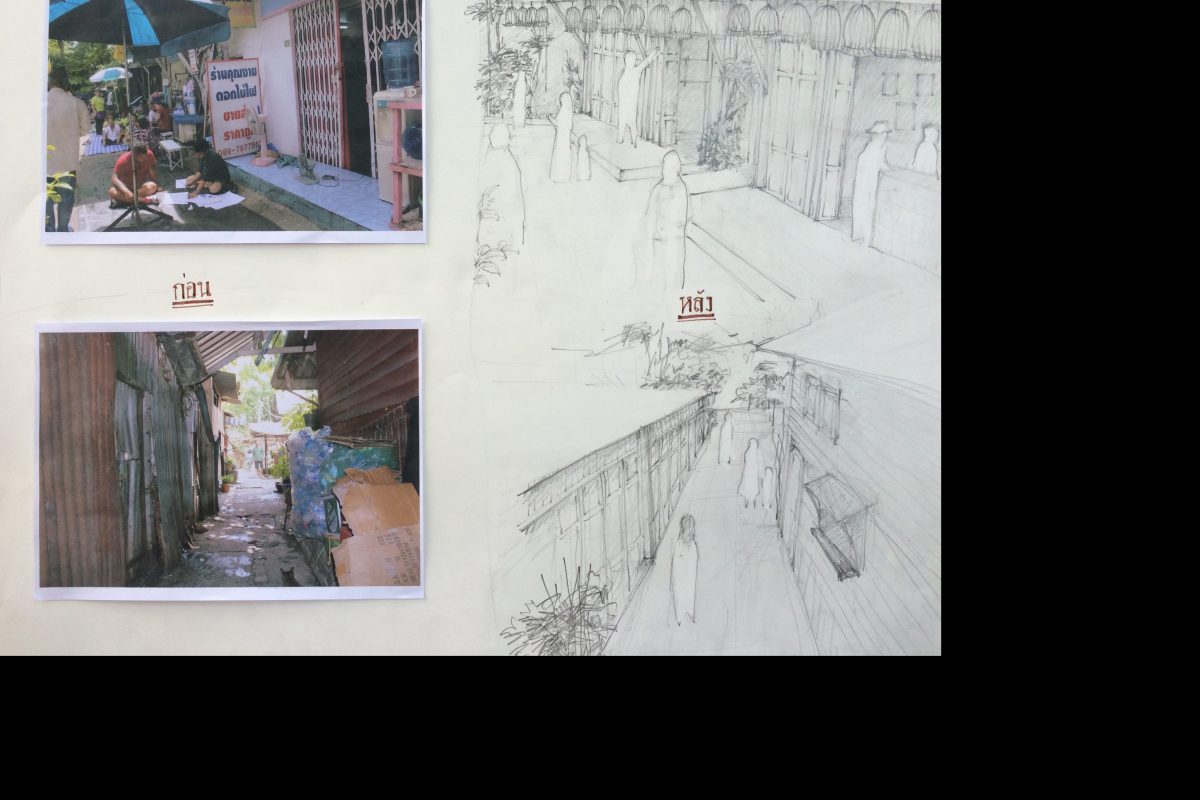

Photo courtesy of MOR and FARMER

Jiropaskosol discovered that, in addition to graphic design, he actually possesses another skill—reading people’s minds through their body language. He said that he acquired the skill from his days working at B-floor, especially from his role as a ‘facilitator’ working in a community workshop back in 2015. “I personally like works in the realm of drama and theatre because it’s something that really touches people. I started questioning what communication design really was. The last year of my office, Noncitizen, I took 6-7 of my interns to work on a communication design project with a group of homeless people in Sao Ching Cha area of Bangkok because I was asking myself really hard questions about whether communication design should actually be created for the people who really want to communicate something but didn’t have the chance or the tools to do so.” The community project didn’t get to be developed into an actual work project for they were unable to turn the homeless individuals into an actual subject (otherwise it would end up with the designers get all the name and appreciation while the homeless people remained unnoticed and neglected like they have always been). Not long after, he participated in the co-creation workshop in Chum Saeng district, Nakhon Sawan province, a big platform that gathered community architects from 20 countries to work with a local community in the area.

From the initial intention of being there just as an observer, Jiropaskosol was asked to be a part of the policy unit, working as an English translator and mediator between the policy experts and a team from Community Organizations Development Institute and other units participating in the project. “I first thought that I would be with the transportation unit because I was thinking that perhaps they would ask me to design some signage considering my graphic background, I would be able to do it. But they put me in policy, which was an entirely different territory for me in terms of the experience working in the realm of design. It was like preparing to go to war. It used to be getting a brief and working on a design. But here, everyone threw in their requirements and designers would start working right then and there. I wasn’t confident at first. I didn’t bring my computer with me. Not even a power outlet. So, what I did was I took out a pen and a paper and started writing, explaining. Gradually, I began to understand that this is probably one of the skills of being a communication designer.”

Photo courtesy of Trawell Thailand / Suwicha Pitakkanchanakul

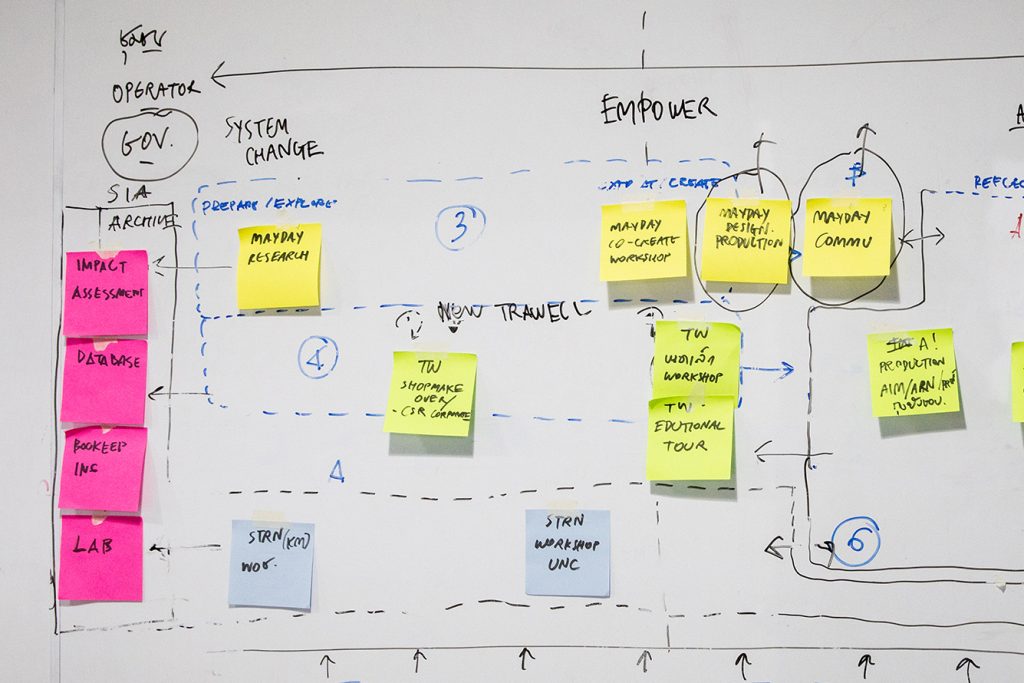

Many are perhaps confused by the term ‘facilitator.’ No sweat, because we are too. A facilitator, to our understanding, refers to the person who facilitates and procures whatever that is needed in order for a mission, a task or a project that is ongoing, to complete its objective. “Being in the policy unit, I had to work with other groups that were involved in the workshop, and sort of map everything together. It was as a result of this experience that I was able to learn about my new potentials. I got to work as a facilitator again with the Mahakan Fort project.” His role is to lead the process, observe the rhythm and the flow of the way things are carried out. He incorporates the skills when he was collaborating with theater companies, which is basically scanning the emotions of participants, from the topics they talked about, to the ways they acted, including their facial expressions.

After the Mahakan Fort workshop, Jiropaskosol initiates a network called ‘SATARANA,’ a voluntary-based project that introduces him to other individuals who share the similar idea of public-consciousness. Jiropaskosol mentions how the issues that SATARANA is working on and wants to work with are controversial and involve conflicts, most of the time. “Local economy is something that should really be further developed. Mahakan Fort Community was one of the cases. We got paid sometimes, but there were times that we didn’t. For some of the projects, we received funds from the government, while there are also projects where we just sort of become involved in organically. There have been the cases where the briefs are given to us, and if we look at them and the projects are really initiated as a genuine participatory project between the organizer and the community, and if it isn’t against our 5 principles, we will do it.”

The 5 principles he mentioned refer to: (1) prioritizing the people (2) everyone is considered a stakeholder (3) a change must take place creatively (not for clout) (4) every small action can become something bigger and greater and (5) “We believe that everything has to be carried out with consistency, whether it’s working with people, spaces, cities, you always need to follow up.”

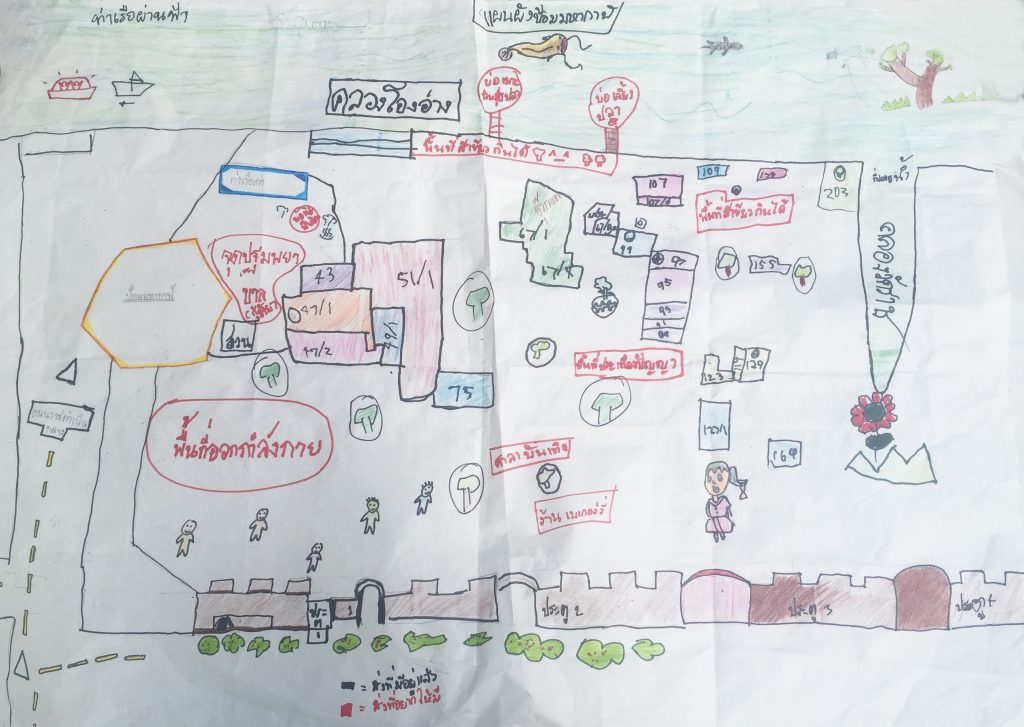

Photo courtesy of SATARANAThe principles paint a better picture of their approach and what they look for before they agree to work on a project. Jiropaskosol further explains that the very heart of his operation is initiating a platform with the word ‘participation’ as the keyword. Everything has to be carried out as a participatory process; from surveying, data analysis, organization of co-create workshops, to the development of the results from a workshop into a prototype, which will eventually be made available to the public. “Our job is to find the true shareholders/stakeholders, not to make them up.”

To Jiropaskosol, a beautiful work isn’t counted as a successful project. “A successful project is the ones that is able to bring a lot of people to participate. Something that inspires and gives birth to movers who will be developing the primary results into something that works in the long run.” To sum up what he has been trying to explain, SATARANA works in designing a ‘process’ for every involved stakeholder from children, community members, artists, designers to prominent figures in governmental agencies to work together on the same platform.

While their strong determination to ‘make the city better’ is not included in the 5 principles, it is the summation of the intention behind all of their projects. When such simple and straightforward objective is addressed, the next question is: wouldn’t it be a less elaborated process if SATARANA were to find a way to be a part of the policymaking process that can ultimately lead to the formation and implementation of local polices, which will help improve the city, by turning all the open-ended conclusions and data they have garnered through all the workshops into the form of political party policies, especially with the constant update the upcoming local election? Jiropaskosol’s answer is that they don’t want to be labeled or sided with any political parties or partisanship.

To Jiropaskosol, developing policies to create ‘a better living standard’ or the whole ‘no matter if it is a white cat or a black cat; as long as it can catch mice, it is a good cat’ sentiment is not exactly something he entirely agrees with. But for the people who have tolerated the life in this city, enduring the unfairness of their poor quality of life, by comforting themselves that they were born less fortunate and that is something they have to live with – we are dreaming of a process where those with the same public consciousness will, one day, turn the idea of a better city for everyone a reality, not just a prototype.