LET’S EXPLORE THE IDENTITY AND UNCERTAIN FUTURE OF ASIAN WITH THE 8TH ASIAN ART BIENNIAL AT NATIONAL TAIWAN MUSEUM OF FINE ART, TAICHUNG, TAIWAN (ROC)

TEXT & PHOTO: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

(For Thai, press here)

As life in Taiwan returns to normalcy, people are starting to spend time in public spaces again and festivals are rolling out dates. October 30th, 2021 marks the first day of 2021 Asian Art Biennial, held for the eighth time now. The image of Taichung residents, young, old, family members and children gathering in The National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art has never been more delightful.

Phantasmapolis, the theme of this year’s biennial, combines the words Phantasmagoria, the title of a science fiction novel penned by Taiwanese modernist architect Wang Da-hong (1917-2018) and the Greek word Polis, which roughly translates to ‘let’s explore the future of Asia together!.’ The scale of Phantasmapolis 2021 Asian Art Biennial isn’t exactly large compared to other biennials where art pieces are found in different venues around the host city. Phantasmapolis, however, can be completed in one day (although it was quite tiring). A team of 5 curators, Takamori Nobuo (Taiwan), Ho Yu Kuan (Taiwan), Anushka Rajendran (India), Tessa Maria Guazon (The Philippines) and Thanavi Chotepradit (Thailand), have selected 60 works by 38 artists.

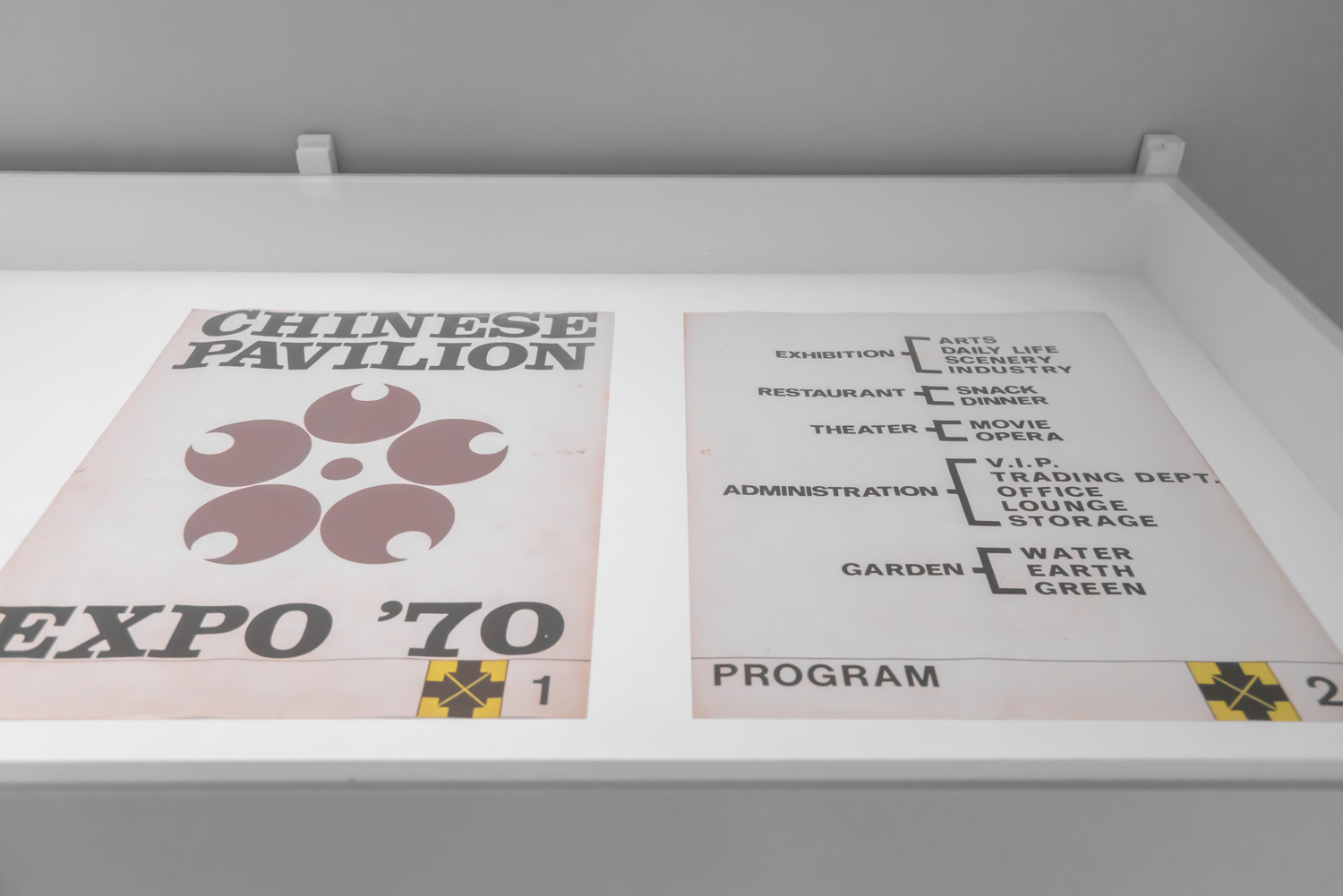

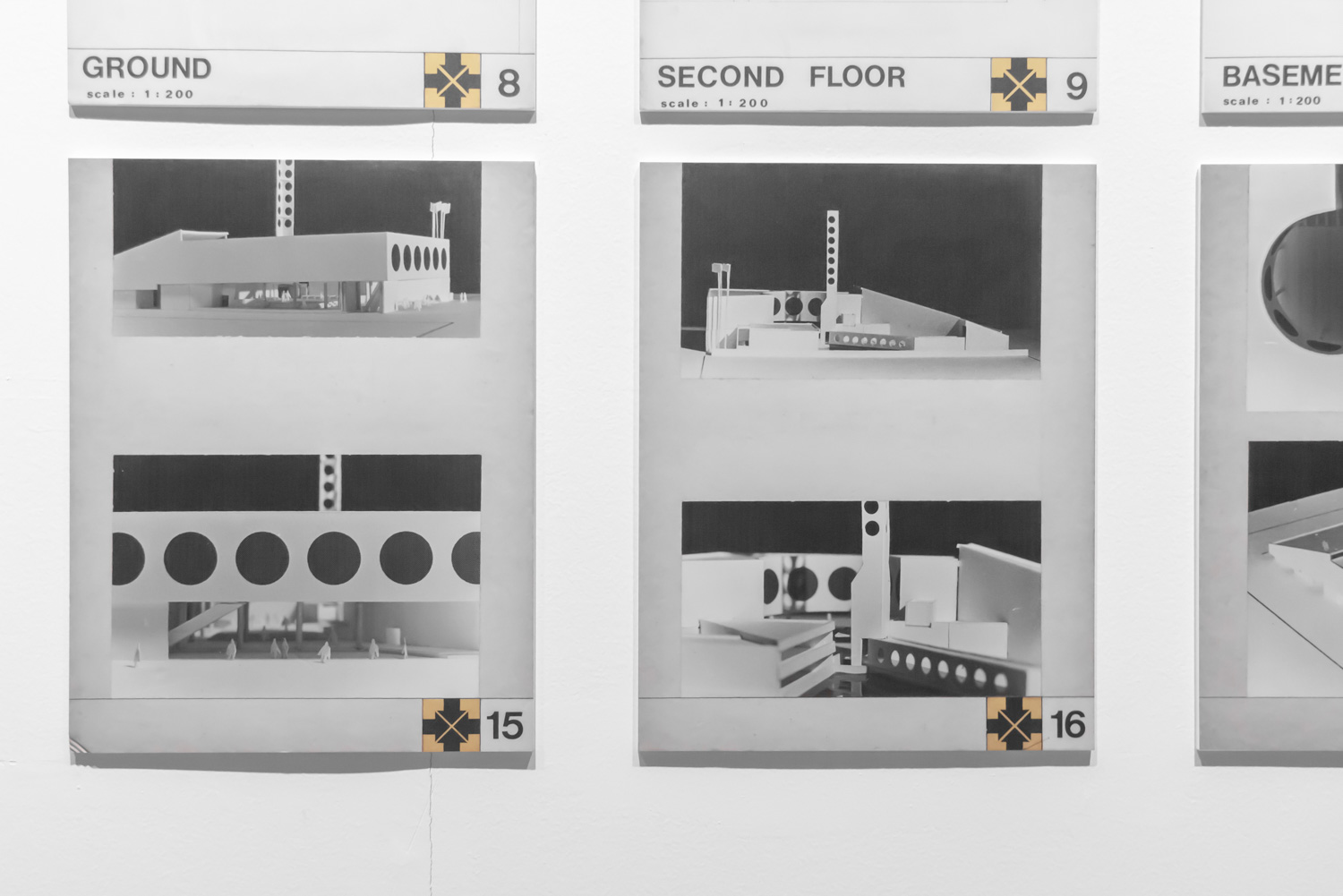

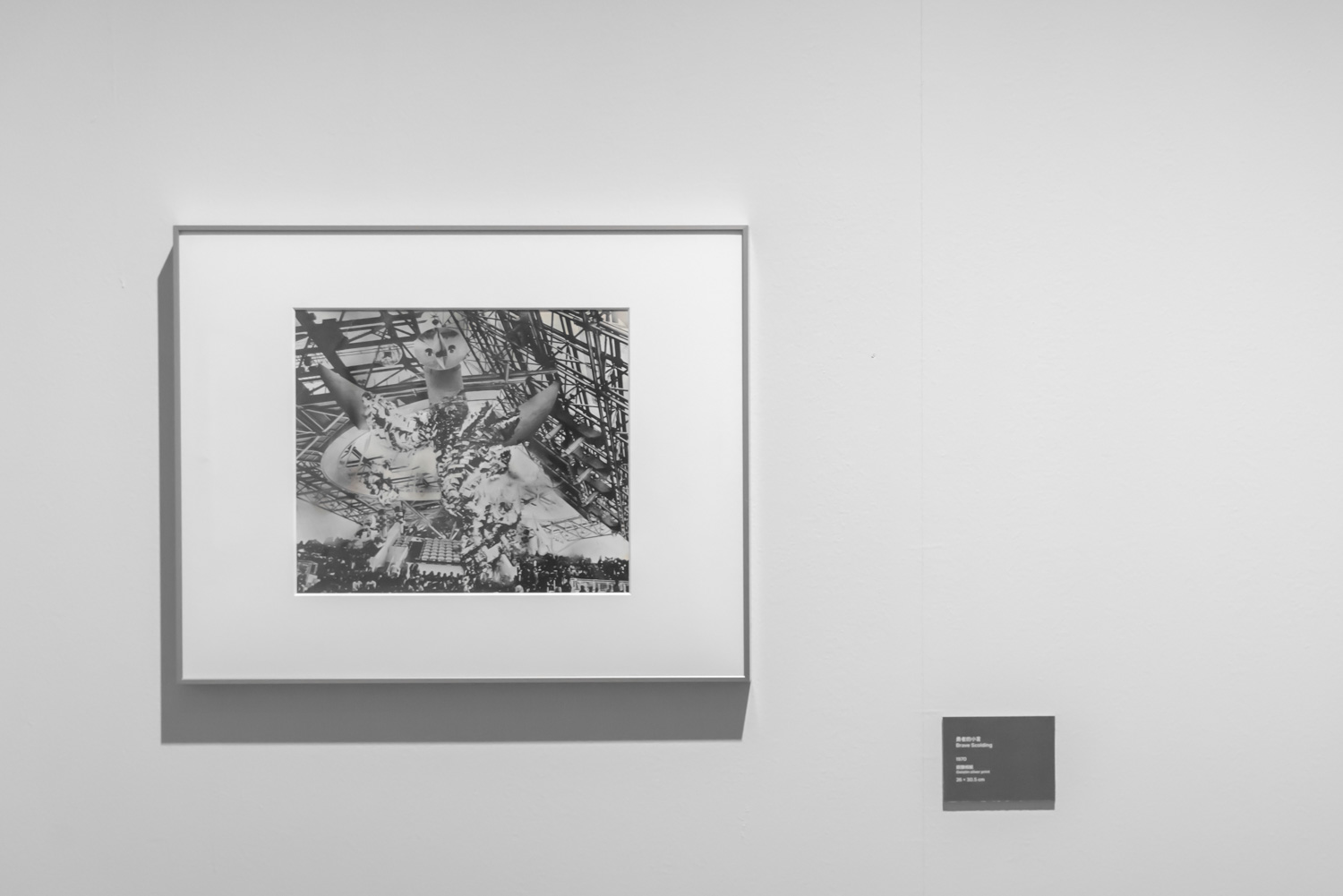

Phantasmapolis begins with an exploration into the future of Asia by taking a look into the past, precisely between the 1960s and the early 1970s when Japan was hosting the Tokyo Olympics (1964) and Expo’ 70 in Osaka, with a monumental archive that comprises drawings and photographs of Taiwan Pavilion at Expo’ 70, which is followed by the resistance (to the future or western nations) occurring in Japan found in the next room (works by Hirata Minoru and Kimura Tsunehisa). The works recount the anti-expos movement initiated by Japanese university students. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics wasn’t just the world’s biggest sports event but it was the moment when the West’s eyes were focused on the East, and Shinkansen Trains and the 500 kilometer per hour speed were what they saw.

One of the curators, Takamori Nobuo, mentioned during the talk that, Songs from the Moon Rabbit, the photograph brought a great number of changes. First of all, it reversed the world’s perception of Asia as a remote zone at the receiving end of the technology to the region that was becoming both the creator and exporter of technologies. Secondly, it introduced technology into Asian science fiction, and thirdly and most importantly, it changed the way westerners saw Asia forever.

Certainly, the West didn’t see Asia as an equal. Takamori Nobuo exemplifies Hollywood’s sci-fi movie, Blade Runner (1982) and the documentary Tokyo-Ga (1985) by Wim Wenders and how the films portray the west’s attitude toward the future of Asia that associates technological advancement to a dystopia. In other words, it’s the future of a ‘high-technology world with low quality-life’. To be precise, it’s how the word technology is added to westerners’ fundamental perception that equates Asia to disorganisation and uncleanliness. These thoughts were encouraged by a climate of fear towards the Japanese in the United States when Japan was gaining economic power, especially when a group of Japanese people were starting to buy land in America.

Takamori Nobuo also points out that the West’s attitude towards the East’s science fiction has its own origin, which is rooted in the stark differences between eastern and western cultures. Western science fiction imagines the future world based on the progressive modernization of a technologically driven modern world whereas Asia’s imagination for the future is heavily influenced by myths, be it India, China (Thailand included) to countries in the far east such as Japan. One of the obvious examples is ancient people’s imagination through the illustration of Trailokya or “three worlds,” Asian people’s perception toward the world and the universe, or even the Mid-Autumn festival or Moon Festival in Chinese culture.

The 1960s, which was the period when the United States and the Soviet Union were fiercely competing over space exploration, ended with the Americans’ victory after Neil Armstrong landed and stepped one foot on the moon. It marks a significant turn in both cultural and political aspects, and it’s probably why the ‘moon’ has become one of the most important keywords of the biennial.

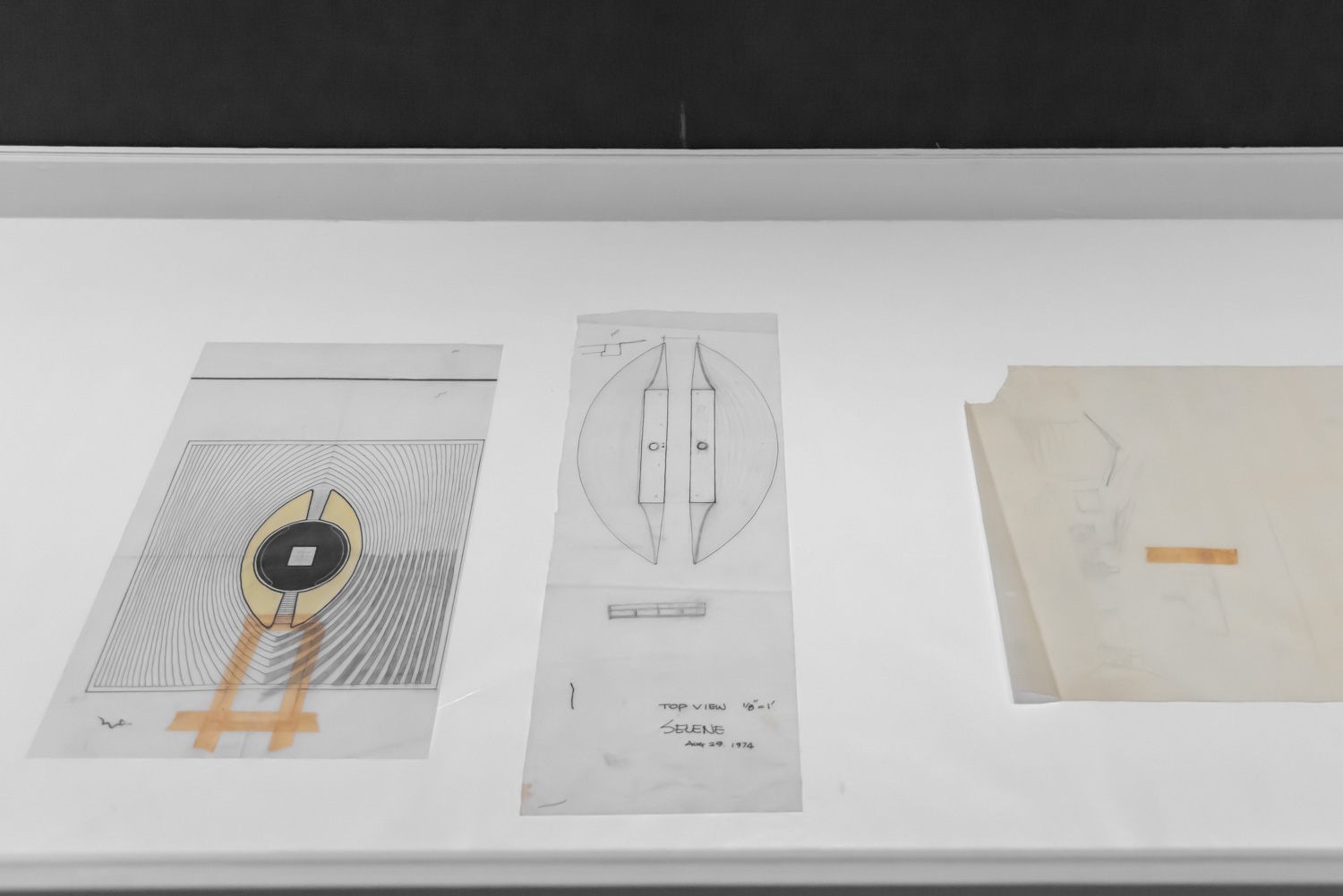

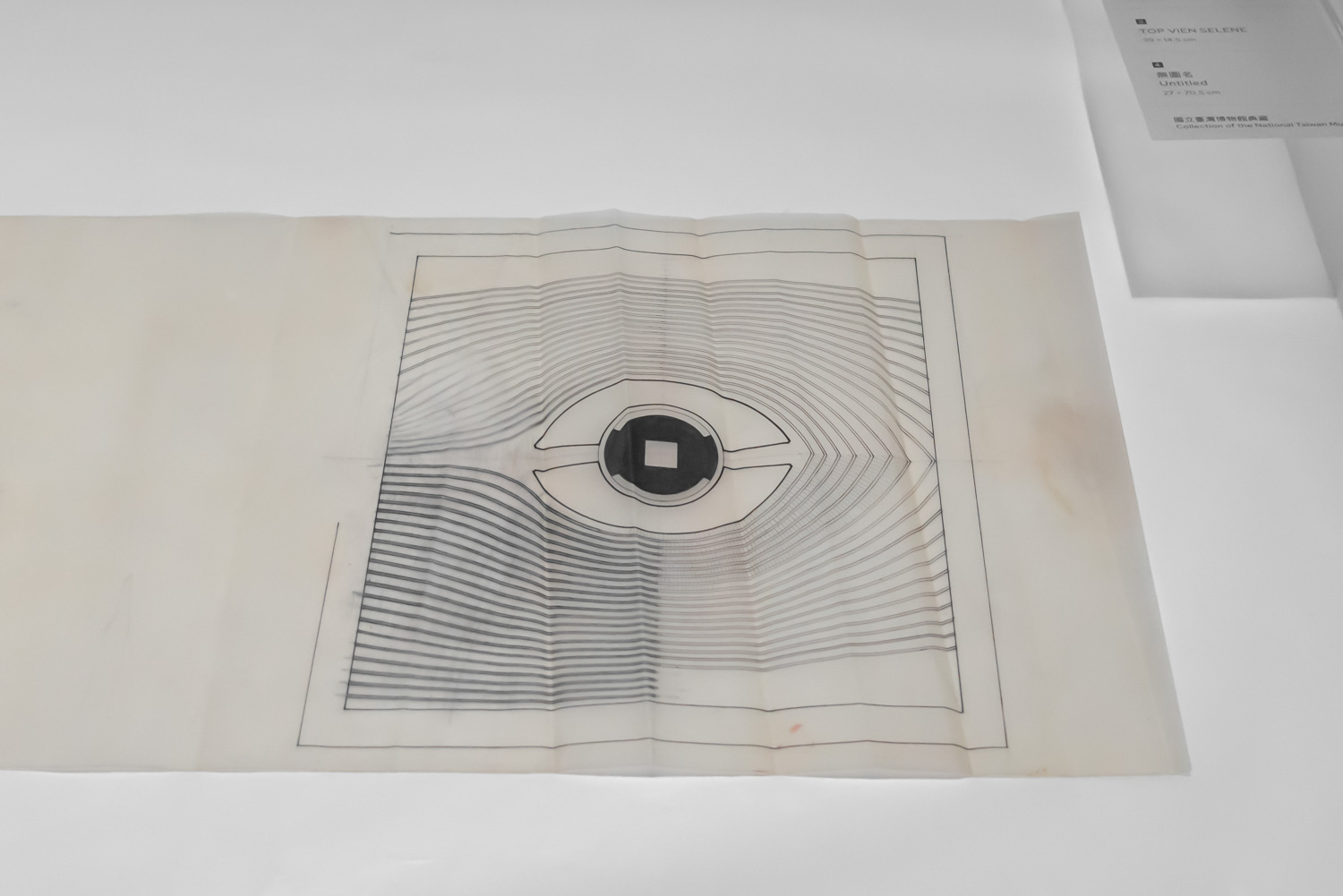

The moon is ubiquitous at Phantasmapolis 2021 Asian Art Biennial. The first one is found in the archive of the project called SELENE—Monument to Man’s Conquest of the Moon. Architect Wang Da-hong completed the design of the 252.71 ft. high monument (the number represents the distance between earth and the moon) before Apollo 11 reached the moon. After the successful mission, the project received support from different sectors before the construction took place in Boston, which if completed, would have been a symbol of the strong relationship between Taiwan and the United States. By the end, the project didn’t take place as Mainland China was starting its intervention.

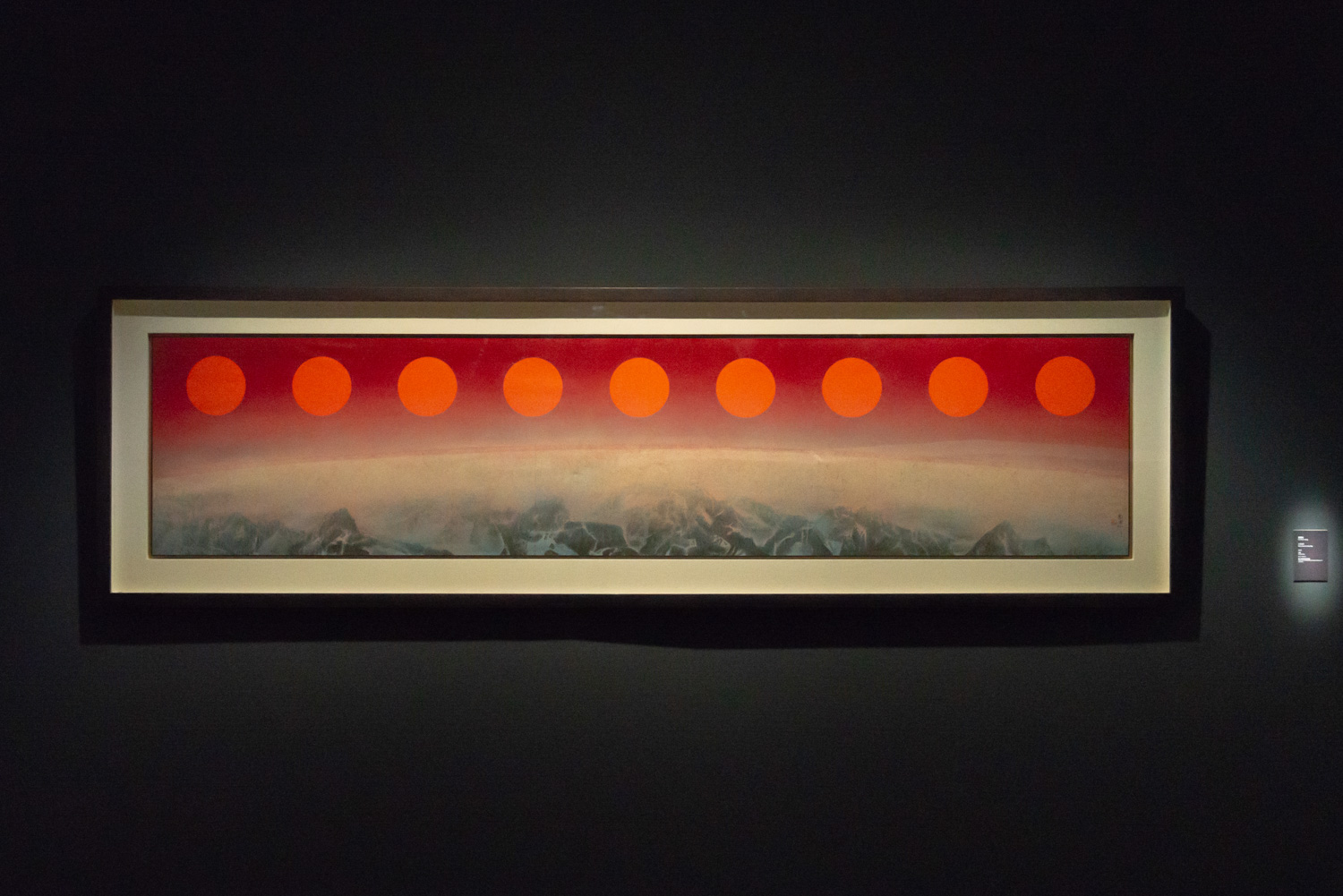

Nine Sun in the Sky (2019)

Taiwan’s accepting and eager attitude toward America’s space exploration during the 1960s was recounted in the documentary about the official visitation of the heroic Apollo 11 crew members and Liu Kuo-sung’s painting, Nine Sun in the Sky (2019). The artist was inspired by the images of the moon photographed by Apollo 8 spacecraft that were published worldwide. Liu Kuo-sung combines his Chinese brush painting technique to Hard-Edge Painting from the Abstract Expressionism movement for the creation of his Space Series back in 1969.

What SELENE—Monument to Man’s Conquest of the Moon and Space Series have in common is the way they both combine the Eastern aesthetics/artistic techniques to Western ideology (the liberal world) in the midst of the Cold War. Recollecting the movement in the time when the rising tensions between China and Taiwan were at their highest levels in decades surely isn’t just a coincidence.

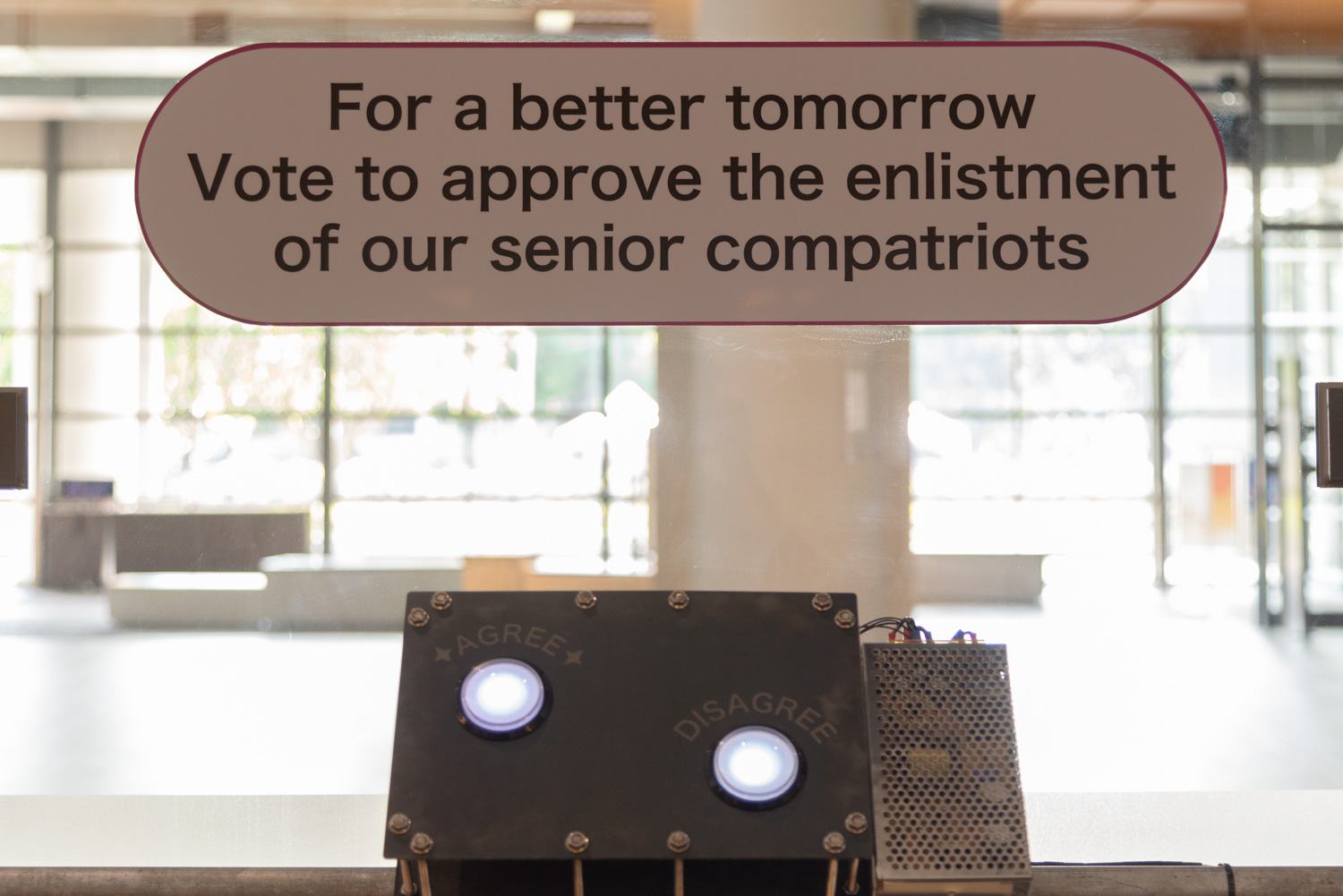

While the content of the exhibition may seem a bit heavy for couples who are on a museum date or families with children enjoying their out-of-home activity, Phantasmapolis can be read in many different ways and levels. The exhibition is fun for it is still an exploration of the imagined future by people in the past whose idea about the year 2000 was a time that was so far away. A Day after a Hundred Years (1933) by Ogino Shigeji (1899 – 1991) talks about the year 2033 using the early stop motion technique. The work imagines humans’ journey into the distant future with a hyper loop, etc. Comparing the work to the more contemporary artists (works created between 2019 and 2021), it’s quite apparent that the descendants of the prior generation didn’t have much expectations of the future. Chen Chun Yu’s view on the Aged Society goes something like this. ‘If in the future, there will be a lot of old people, why don’t we enlist them into the military?’ with the video art, Back to Glory: Make_ _Great Again (2021) accompanied by buttons for spectators to vote if they agree with the idea or not at the exit.

Wrapped Future by Lim Sokchanlina

Wrapped Future by Lim Sokchanlina

Lim Sokchanlina, a notable Cambodian artist, talks about the future that has not yet arrived with her photography series, Wrapped Future, and the captured images of corrugated galvanized sheets that display the ‘under construction’ stage they imply. Alvin Zafra and The Sound of One Hand Clapping (2021) portrays the artist’s journey into the city before lockdown with the captured images that have been re-processed using a special technique. Vietnamese artist, LE Giang, wandered through the rural areas in her country before simulating a disappearing form of vernacular architecture into sculptural pieces that mimic architectural remains and ruins with Vestige of Land (2021).

Vestige of Land (2021)

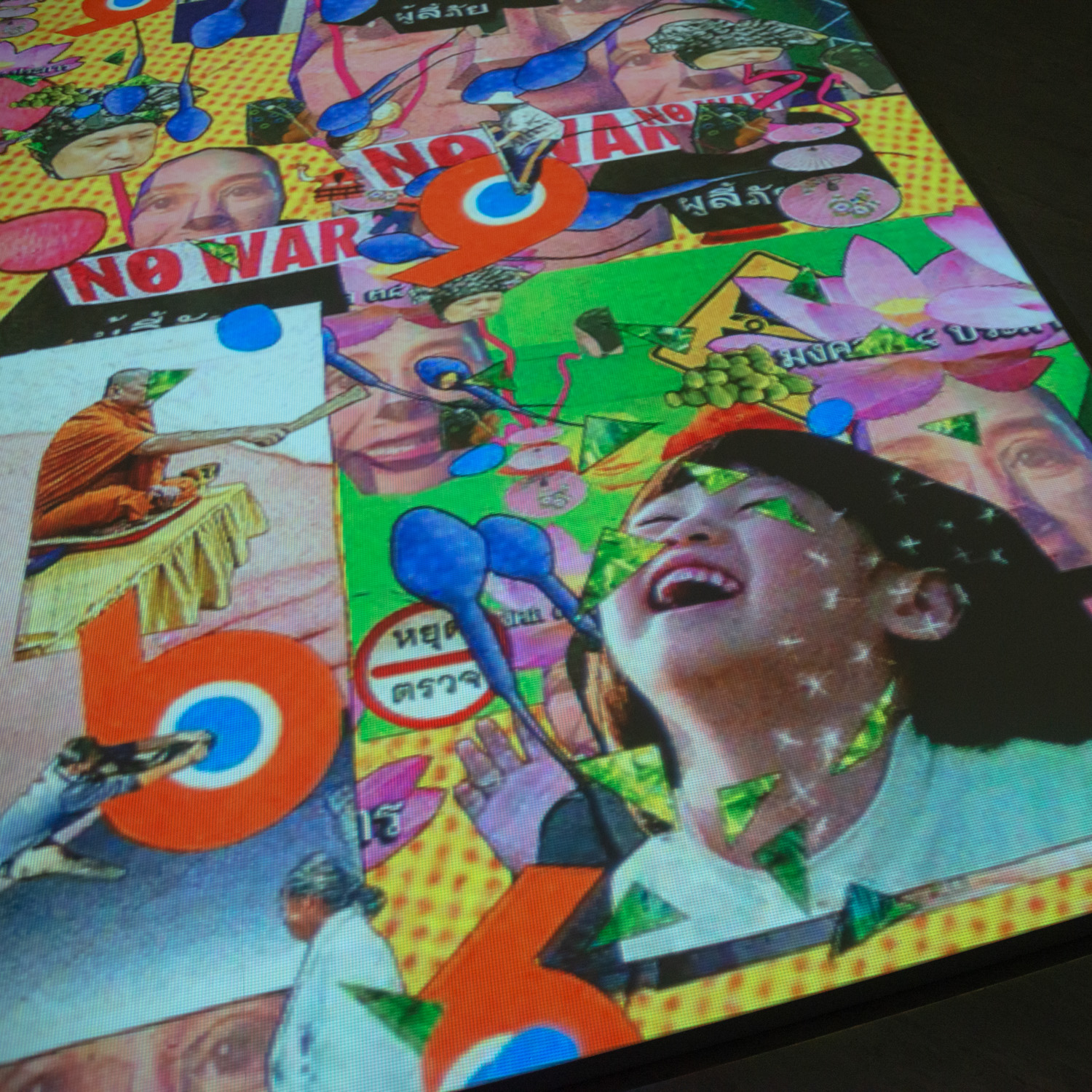

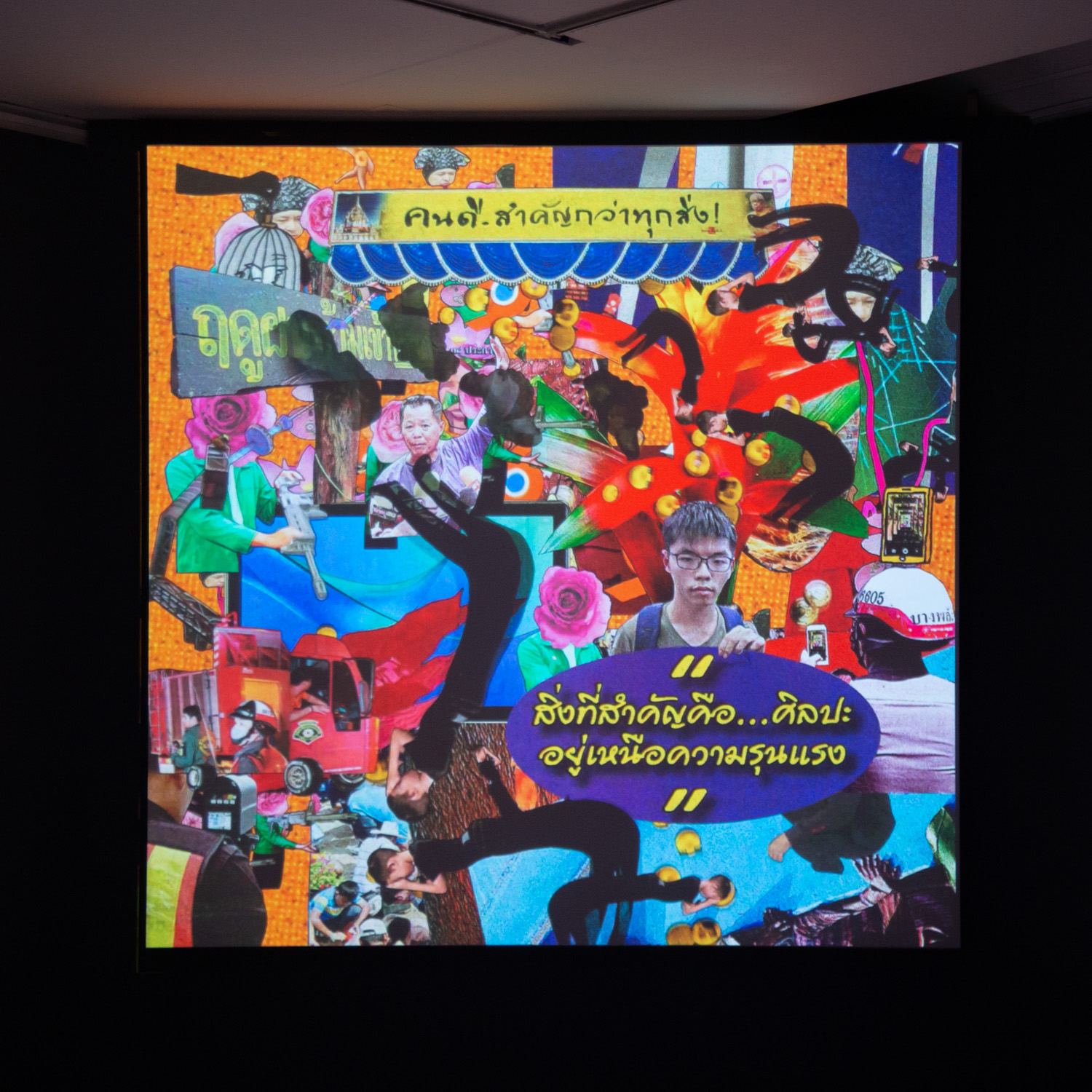

From Thailand, Chulayarnnon Siriphol’s Gives Us A Little More Time (2020) features a video art piece that challenges Taiwanese (and Thai) viewers’ interpretation, and a series of collages that the artist has created since Prayuth Chan-ocha’s overthrow of Thailand’s democracy in 2014. The work that I personally think is a representation of many emotions lingering in the air of this biennial is Escape Route (2021) by Liu Yu + Wu Sih Chin that imagines different unrealistic apocalyptic scenarios and the arrival of the saviour (who still hasn’t yet arrived). “We are all in the waiting room” is the phrase that appears on the screen after the video that sensationalises viewers with footage of the year 2000’s countdown from around the world, which ends with countdown numbers that lead to the beginning of the replayed video. Phantasmapolis is this massive waiting room for the future that has not yet arrived (or perhaps it has arrived but we haven’t accepted the reality we’re living in as the future). As a matter of fact, through the imagined future by the works created in the 1960s, the deceased artists would be disappointed because the future they had envisioned ended up being the world with COVID-19 pandemic and the recurring conflicts that feel like a rerun of the same movie.

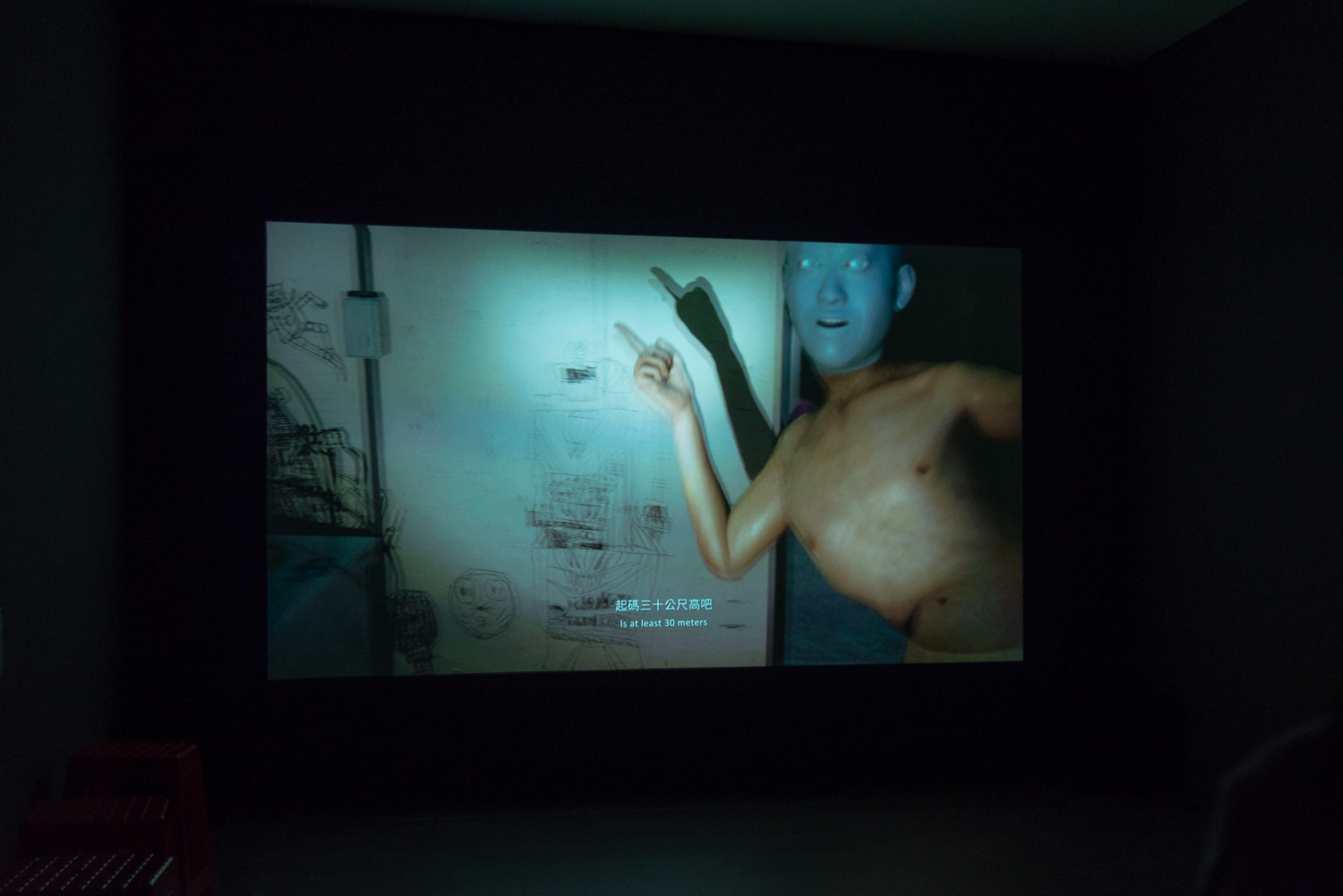

Let’s just say that the future of Asia isn’t all that bright, at least through the eyes of these artists. But another interesting subject worth mentioning is the haunting sci-fi elements of many of the works at the biennial. The most extreme one has to be the video art by Taiwanese artist, Li Yi Fan, titled How Do You Turn This On (2021). Featuring an eerie-looking creature created from computer graphic technology and an erratic conversation. The artist talks about technological advancement and asks the question that ‘even you call yourself a creator, are you sure you can control what you’ve created?’

How Do You Turn This On (2021)

The word ‘Phantasmapolis’ as the theme of the biennial is a hint in itself that the future may not be beautiful since the meaning of ‘phantasms’ is associated one way or the other with a phantom-haunted house. It’s another reason why the imagined future or the sci-fi conveyed in the exhibition aren’t exactly pleasant for the viewers, but they certainly do their deeds in encouraging everyone to question their Asian identity and the future of the region.

Looking Back to the Future curated by Anushka Rajendran

Apart from the previously mentioned works, there’s also a Video Art Project, Looking Back to the Future, curated by Anushka Rajendran (available online at the festival’s official website) and Beyond Time and Sex: A Opsis of Queer Sci-Fi in Asia, a research project by Tessa Maria Guazon and Taiwanese academic, I Chun (Nicole) Wang, which looks into the Sci-Fi Queer moment in Southeast Asian countries and the Philippines. The event also includes the non-exhibition activity such as Songs from the Moon Rabbit, the talk that took place on October 30th and 31st, as well as a number of film screening sessions.

Phantasmapolis 2021 Asian Art Biennial takes place between October 30th, 2021 and March 3rd, 2022 at National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art in Taichung, and Mongolian and Tibetan Cultural Gallery and Digital Art Center in Taipei in February of 2022. Hopefully, Taiwan will open the country for Thai people to see the Biennial before it’s over.