KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE AND JENCHIEH HUNG INVESTIGATES THE OCCURRENCE OF ‘FORM’ IN SCENIC ARCHITECTURE THROUGH SOME PART OF 12 PROJECT’S ANALYSIS IN THE BOOK ‘THE REBIRTH OF FORM-TYPE’, REVEALING THE EVOLUTION AND PIVOT OF CHINESE ARCHITECTURE SINCE THE 2000s

TEXT: KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE & JENCHIEH HUNG

PHOTO COURTESY OF SCENIC ARCHITECTURE OFFICE except as noted

(For Thai, press here)

The 2000s (the years between 2000 and 2009) were a time period when China saw a tremendous leap in its economy with major cities hosting different large-scale events in hopes of stimulating economic growth and urban developments, and bringing a spirit of urban civilization to the population. From the Beijing Olympics in 2008 to Shanghai World Expo and Asian Games in Guangzhou, which both took place in 2010, the massive waves that erupted in China at the time have birthed a vast number of buildings and public utility systems across these cities. The Chinese Government’s decision to open up the country to manifest China’s incredible potential to the world has brought in an army of world-renowned architects. The iconic buildings that are designed and built include the National Stadium (2008) in Beijing by Swiss architecture practice, Herzog & de Meuron, the Shanghai World Financial Center (2008) by the US’ Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (KPF), and the Guangzhou Opera House (2010) by Zaha Hadid’s London-based firm, to name a few.

The opening of the country in the 2000s has not only boosted the country’s economy and urban expansion, but also prompted Chinese architects, who were born in the 1970s, graduated and were working overseas, to return to their home country and establish their own practices. Such a movement gave birth to a group of young, progressive architects who would later have a significant role in the country’s contemporary architecture today. Architects such as Zhang Ke, Ma Yansong and Li Hu chose Beijing to be their operation ground. Meanwhile, over on the other side of the country in an economically advanced city such as Shanghai, a population of young generation architects with educational backgrounds and work experiences in the US and Europe began making names for themselves. Among the new waves is Zhu Xiaofeng, the founder of design practice, Scenic Architecture Office or 山水秀, which translates to landscape or terrain.

Photo: Hanzhi Gao

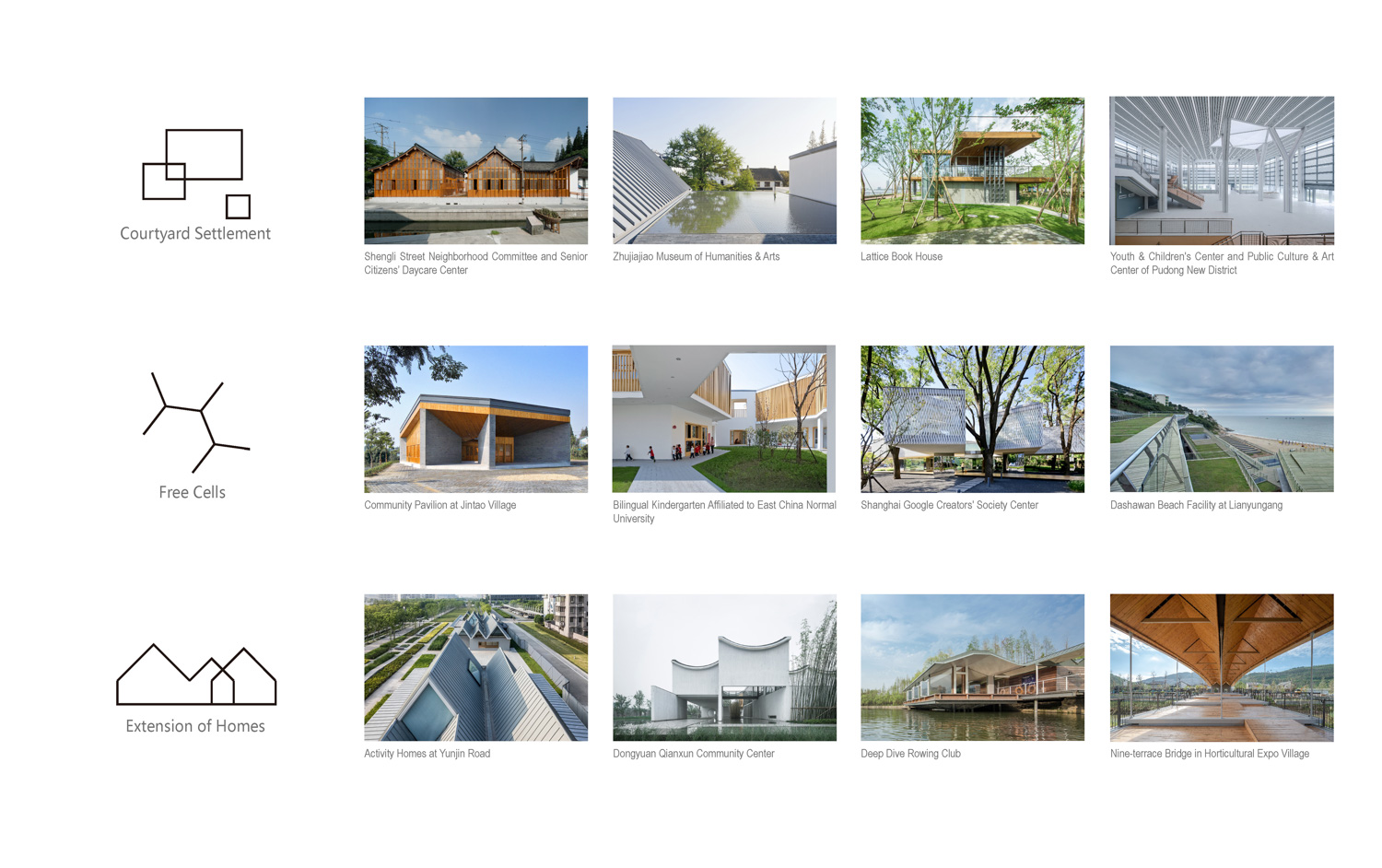

Zhu Xiaofeng spent seven years in the US where he studied and earned his master’s degree from Harvard University before he started working at the New York branch of KPF. He returned to China and founded his own design studio in Shanghai in 2004 with an intention to explore architecture as well as the traditional and contemporary cultural landscape of the Yangtze River Delta region, encompassing Shanghai and Jiangsu province where he grew up. His goal is to incorporate and apply the western way of thinking and work methods to the creation of his own works of architecture, which are the combined result of body and mind, ontology and interactions. Xiaofeng analyses the core of the three-part relationship in the book, ‘The Rebirth of Form-Type,’ where he selects 12 projects by Scenic Architecture Office throughout the 18-year history of the office. The 12 works are grouped into three categories; Courtyard Settlement, Free Cells and Extension of Homes. The three typologies are used to define architectural boundaries and layout, following Xiaofeng’s belief that these forms can be transformed into a mediator of cultural memories, energy and constantly evolving connections between humans, nature and society. Following is an elaborate take on the three terms and ideas Xiaofeng proposes in his book.

Feature works of Scenic Architecture office

Courtyard Settlement

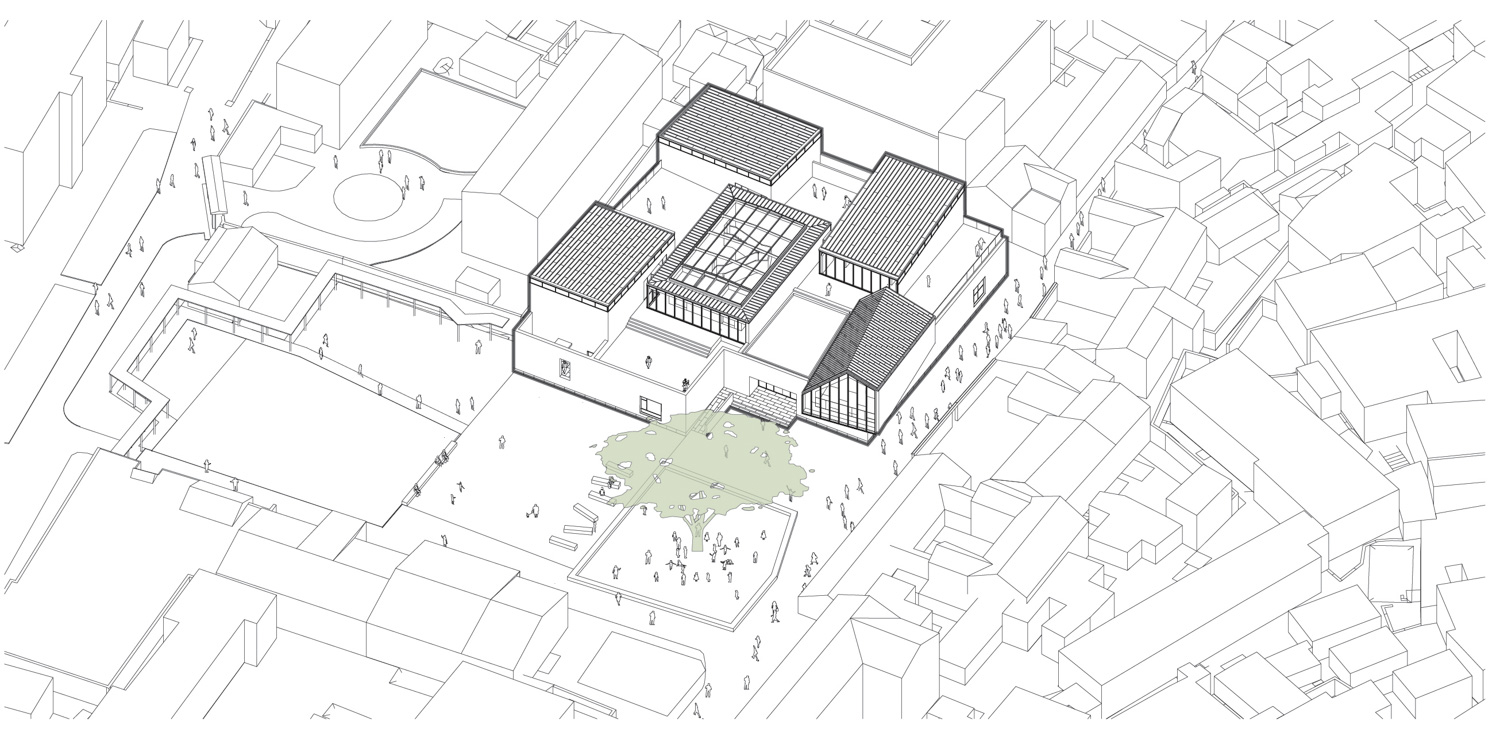

Courtyard Settlement is an approach to building orientation, which emphasises on the use of enclosures to create a new space that enhances a sense of serenity. It’s an approach to access the core of space and enable interactions between humans and nature, similar to traditional Chinese architecture where a courtyard is designed to indicate a building’s accessibility and division. Zhujiajiao Museum of Humanities & Arts, one of the most prominent attractions in Zhujiajiao, the ancient town located on the outskirts of Shanghai, showcases Xiaofeng’s intention to materialize a settlement of a courtyard and enclosure of spaces. The attempt is evident from the layout of the main hall, which is positioned at the heart of the building, and surrounded by a series of white walls and a sculpture-like staircase wrapped in wood, placed at the centre underneath the skylight. In addition to the courtyard on the ground floor, another cluster of courtyards are found on the second floor, placed in an alternating arrangement between the architectural masses and spaces. The spatial manipulation curates a connection of different architectural masses with the presence of spaces, purposefully reflecting the image of nature and the surrounding community into the building.

Diagram of Zhujiajiao Museum of Humanities & Arts

Zhujiajiao Museum of Humanities & Arts l Photo: Iwan Baan

Zhujiajiao Museum of Humanities & Arts l Photo: Iwan Baan

Free Cells

When a form that frames and covers a building diverges, emotional connection is what remains while nature exists to support and grant freedom to those free cells. Shanghai Google Creators’ Society Center (Huaxin Business Center) is a branch of an architectural existence in a way that perfectly intertwines the built structure to the surrounding context. The project is situated on one of the main roads in the southwest of Shanghai where six ancient camphor trees are growing. The openness of the space and its coexistence with the trees is the main concept that Xiaofeng uses with the design. The elevation of the building’s ground floor and the wrapping of the architectural structure with reflective stainless steel skin make the four buildings appear as if they were floating in the middle of its natural surroundings. The built structures find their ways in between the trees, offering the architecture freedom from all the confinements that the architect created.

Huaxin Business Center Plan

Huaxin Business Center and surrounding l Photo: Su Shengliang

Extension of Homes

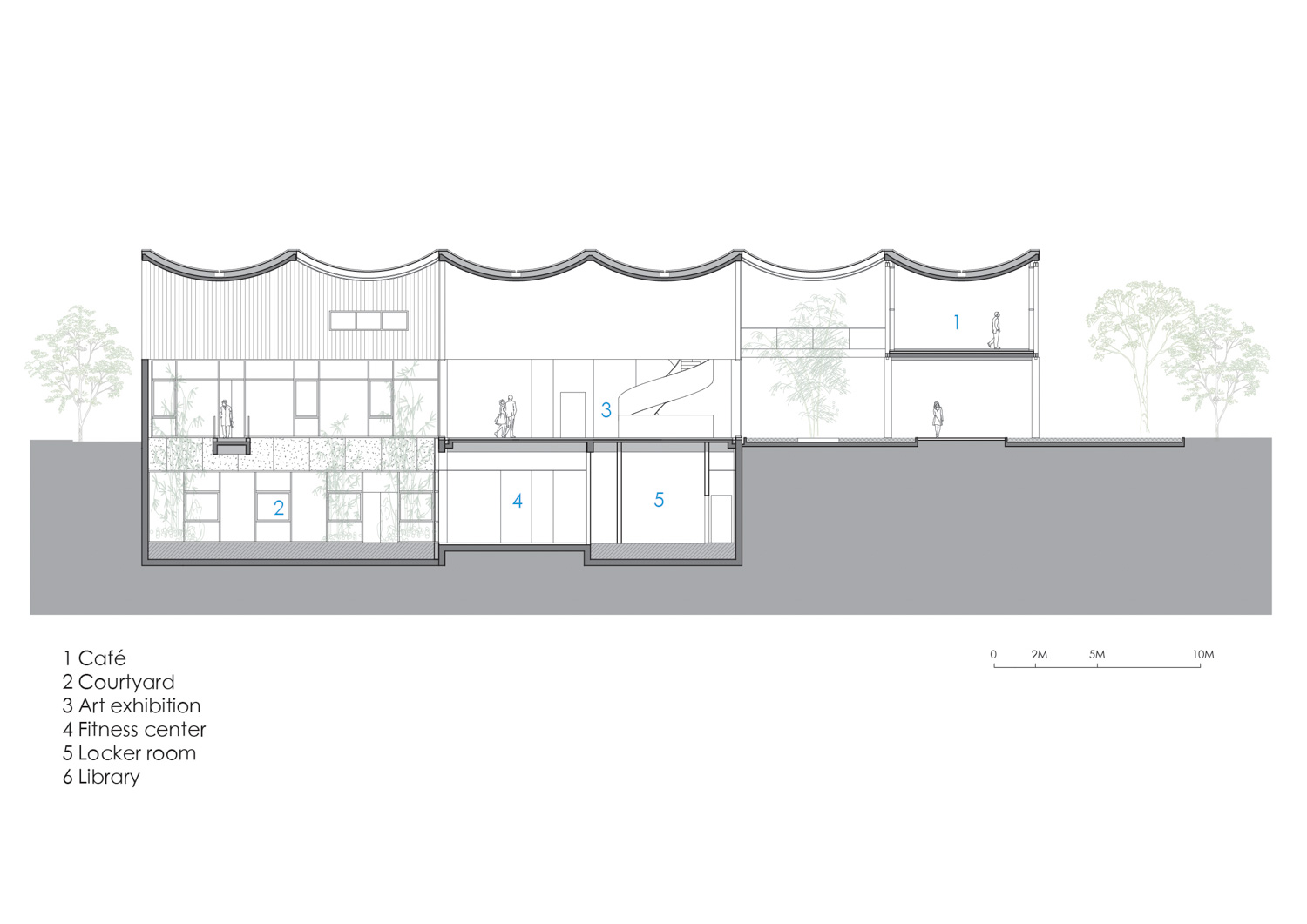

The image of a house with an extension that turns a roof into a functional, usable space or how the space underneath the same roof can facilitate an interesting connection and reminiscence between contemporary and vernacular architecture. Dongyuan Qianxun Community Center is a public building in Suzhou, a city to the west of Shanghai. Xiaofeng experimented with load-bearing walls with the use of stacked walls as deep

beams to define the functional and negative spaces inside of the building. While the reverse exposed concrete roof renders the feeling of being underwater, a meaningful connection with the traditional architectural typology of the southeastern Yangtze River Delta region known as Jiangnan Houses is created. The superimposition of walls and physical characteristics of the roof structure give birth to a work of modern architecture that is still filled with traces of culture and interactions with natural light and shadow.

Bearing wall in Dongyuan Qianxun Community Center l Photo: Dongyuan Design

Dongyuan Qianxun Community Center Section

There is an undeniable influence in the backgrounds and interests of Chinese architects born in the 1970s. Their search for the deviated and unclear origin of their country’s culture caused by the Culture Revolution, which is a part of their childhood experiences, combined with the extreme development of China during early days of their architectural practice, have collectively resulted in two apparent directions of the works of these Chinese architects. The first one is the design of modern buildings and certain culturally rooted traits they possess, which is one of the distinct qualities of the Scenic Architecture Office’s body of work. Another direction is the design that embraces and reflects modernity and advanced manufacturing technologies that do not only equate but surpass those of developed, civilised countries. Both directions and approaches still embody Scenic Architecture Office’s attempt to seek for new possibilities from locally sorted materials, remaining roots and traces, and future capabilities. It would be quite interesting if one day we have a chance to see future works by Scenic Architecture Office that actually integrate the two approaches together; the kind of integration that will result in Xiaofeng’s architecture to bring endless and dynamic connections between humans, nature and society, as well as the unforeseeable future.

Photo: Hanzhi Gao

scenicarchitecture.com