ART4D TALKS TO KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE ABOUT THE PATH SHE HAS CHOSEN FOR HERSELF, AND ALL THE INTERESTING STORIES THAT HAVE HAPPENED ALONG THE WAY. FROM THE ONLY ARCHITECT WHO HAS BEEN CHOSEN IN THE RENZO PIANO BUILDING WORKSHOP TO THE NEW CHAPTER OF HER VERY OWN OFFICE CALLED HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH

TEXT: PRATCHAYAPOL LERTWICHA

PHOTO COURTESY OF HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

From Paris where she was the only architect chosen from thousands of applications and offered an internship position at the Renzo Piano Building Workshop, to Hong Kong and China where she worked as a senior architect, a university professor, an exhibition curator, and writer, Kulthida Songkittipakdee’s track record is an intense and extensive one due to the many roles she has taken. She is now entering a new challenging chapter with the opening of her very own office called HAS design and research with her partner Jenchieh Hung. Together, they are building a continually growing portfolio that includes projects in both Thailand and China. art4d talks to Kulthida about the path she has chosen for herself, and all the interesting stories that have happened along the way.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

art4d: In the book ‘Arch Life Rhythm’ you talked about how your family was initially against the idea of you studying architecture, so how did you end up taking this career path?

Kulthida Songkittipakdee: I think most parents from my parents’ generation tend to have this attitude that architects have to work hard without making that much money. But I knew I wanted to be an architect since I was ten years old. I was visiting a relative’s house and one of my cousins was an architecture student. Seeing my cousin working on a project, I felt like ‘this is what I want to do.’ I like art, I like drawing and inventing things. I like sci-fi novels and I like creativity that is based on reality. I told them since then that I wanted to be an architect. I was adamant to do what I liked and wanted to do.

And I’ve been walking on this path ever since. I got into Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Architecture. I think deep down they were glad that I got accepted into such a prestigious university but they were quite worried about the exhausting load of studying I was going to have to go through. I remember when the entrance exam result was announced and my father said something like ‘you choose this path, so you have to endure it no matter how hard it will be.’ So, I was driven to give all I have and I wasn’t ever going to give up. Not having their full support was like this drive that pushed me forward to achieve my dream.

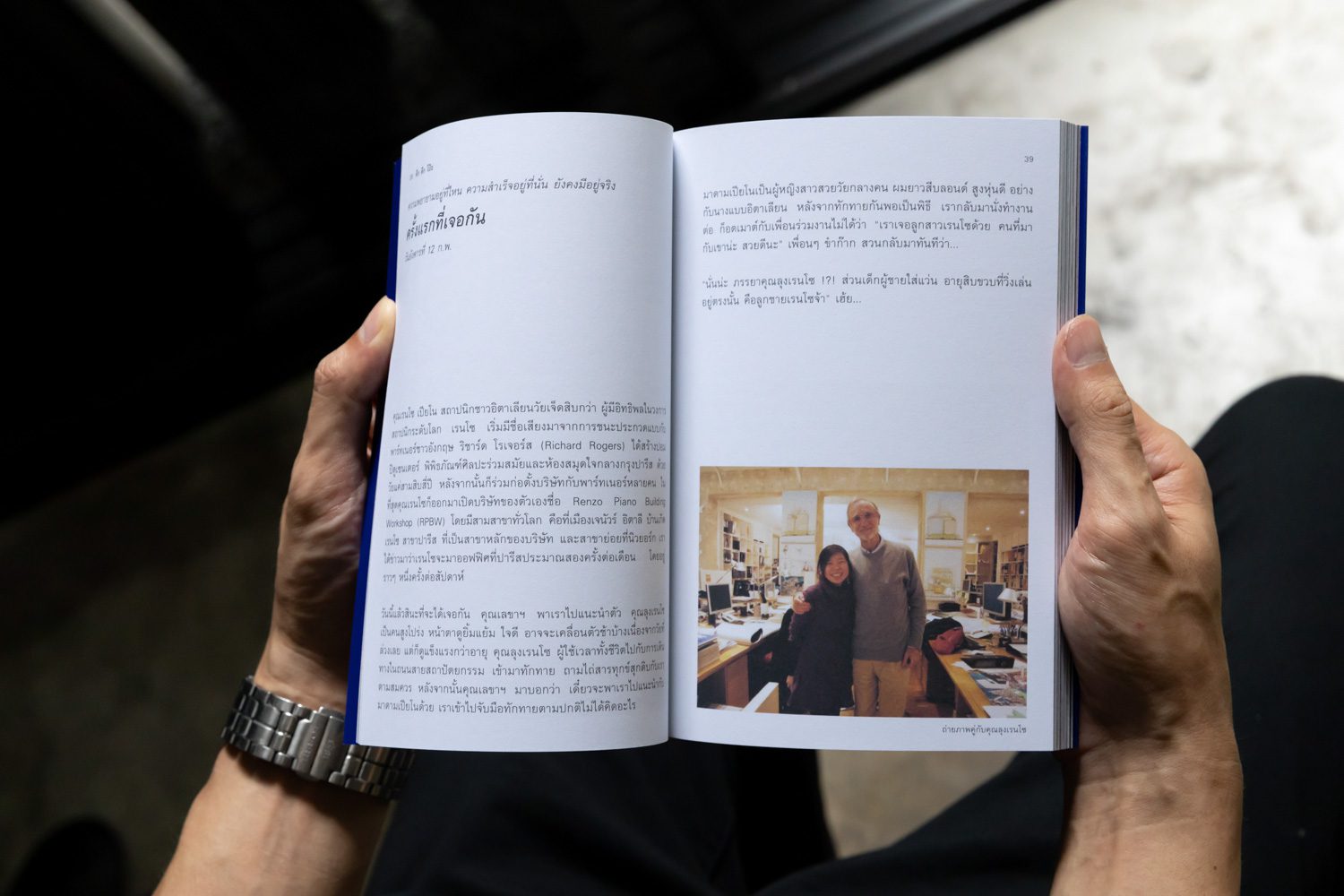

Eventually, I graduated, with honors, and got a job. My parents stopped worrying because I proved to them that I had succeeded in the goal that I set for myself. I think they saw how motivated I was to work in this profession. When I was offered the internship at the Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW) in Paris, I think that was a major turning point of my life and a result of my hard work and dedication. When my family heard the news, they were very proud and told me ‘you’ve chosen the right path,’ from the beginning where they couldn’t see how I could be working in this line of work, to them finally accepting that I made the right choice, having chosen this profession for myself.

Photo: Kulthida Songkittipakdee

art4d: Your experiences are incredibly diverse and extensive, from working in Thailand after graduating, to doing an internship at RPBW in France, then to Hong Kong and China, what have you learned and what are the differences that you have witnessed along the way?

KS: The differences are quite jarring (laugh). After graduation, I started my job at A49 and luckily when I got in, the projects that were handed to me allowed me to work on different stages of the work process, from concept stage, creating working drawings, participating in design development, talking with engineers, going for site inspection, to finally seeing the buildings I designed completing construction. They were mostly small-scale projects but they helped me see the big picture of how a piece of architecture was created in Thailand.

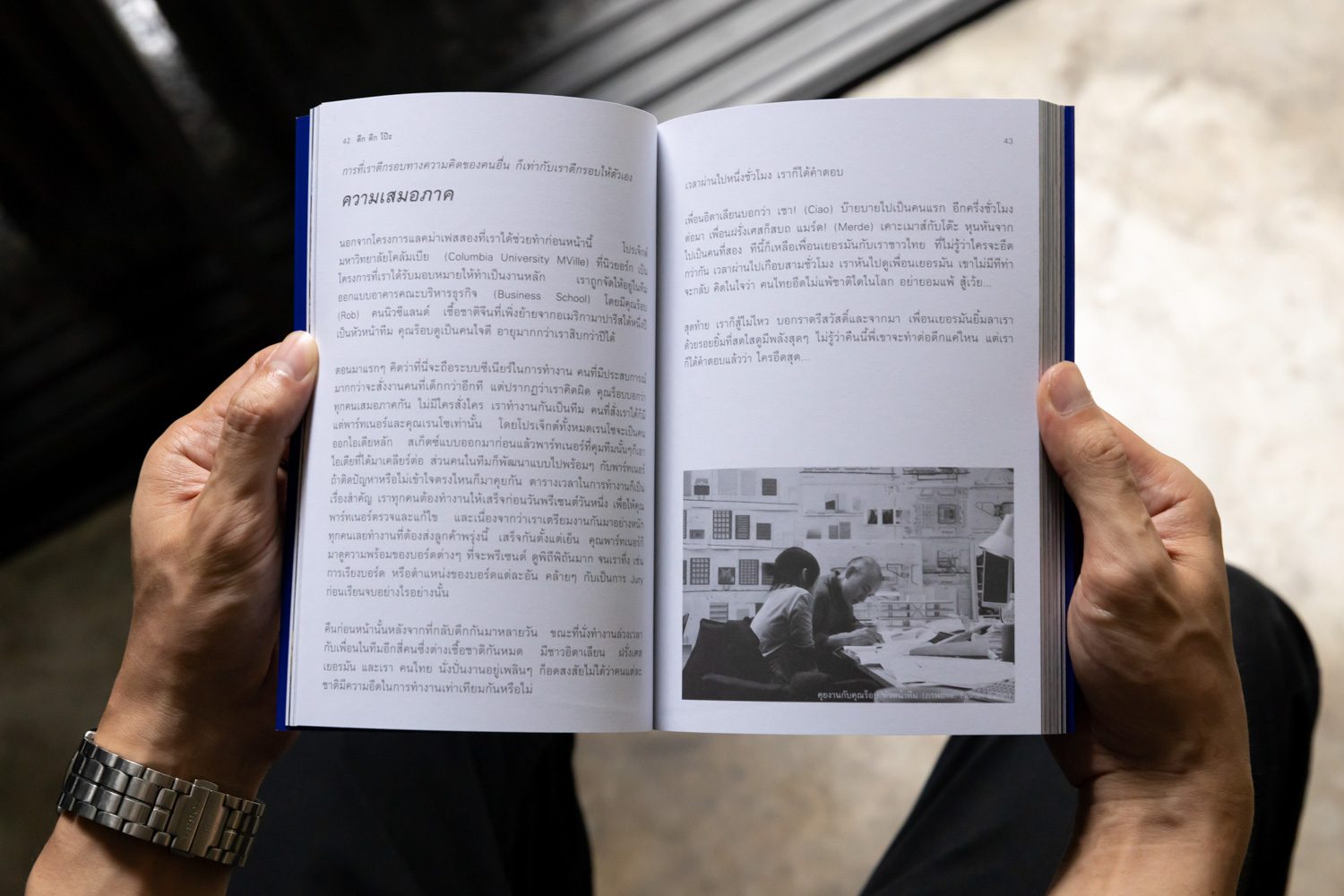

Then I applied for an internship with Renzo Piano in France and I was the only architect chosen from all the applications submitted from around the world. At RPBW, I got to work on projects that were larger in scale, working with a bigger team and my responsibilities would encompass the early stage of the design, to designing the details. Everyone on the team would have their own board, and what was shown on that board were updates of what we were working on in a span of one week, so that we could discuss them with the rest of the team members. When a week passed, the team would review your work with the partners. And each month, Mr. Renzo would come to Paris and give us his reviews on all the projects. It gave me the opportunity to see each project in a big picture, and observe how each person had a different style in the way they studied a project because the firm hired people from so many countries with different nationalities.

The duration of each project was longer compared to the work I did in Thailand. With each stage, architects were given a period of time to study a project in greater, intensive detail. Each presentation took almost an entire day because everyone was very well prepared and packed with back up information.

When I moved to Hong Kong, I was working with this company called Rocco Design Architects Associates. Rocco Yim is one of Hong Kong’s architectural masters and while working there I was required to have a clear knowledge and understanding about each project’s concept. I had to be able to tell what Stage 1 was before moving on to state 2 and why it could progress to stage 3. I got to learn about the thought process and how ideas and data were processed in quite a straightforward way. Then I was promoted to oversee project management, working on detailed drawings, and coordinating with consulting firms to facilitate the construction and completion of projects.

Then there was a certain incident that led me to relocate to Shanghai. There I got a job working for the Shanghai branch of an American practice, NBBJ. It was the last firm I worked for before opening my own office. The experiences I had garnered and my commitment and dedication were well recognized by my boss, and my career took off within a short time period. I was working as a senior architect, then the head of the design team, and I eventually became the firm’s youngest associate. The projects I was working on were on a massive scale, like a hundred thousand square meters, and I supervised them from the pitching stage to when the entire construction was completed.

Photo: Kulthida Songkittipakdee

After over a decade of working abroad, the most important thing I got from it is the chance to see the entire process of how architecture is created. The experiences have taught me about all the processes, and difficulties we have to go through for a building to be created in each country. If my involvement was superficial, and all I learned were their thought processes, I don’t think I would consider my experiences to be those of an architect working on architectural design overseas.

art4d: Why did you decide to open your own office?

KS: I’m very driven by the work that I do. The more I work, the more I learn. I came across projects that were tough, and there were times when my spirit was low but I followed through with what I committed to do. Living alone in a foreign country, work took up 90% of my time. When I reached the point of stability, I had this feeling of wanting to tackle new challenges. I began with a teaching job, teaching studio design at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool (XJTLU). It was a joint program between Liverpool University and the Chinese university. It was then that I first discovered my love for teaching. I like passing on my knowledge and experiences to my students. It just happened that Jenchieh, my Taiwanese partner, who was working with Kengo Kuma for many years and completed several buildings in China, and has always been interested in contemporary architecture in Southeast Asia, its history and evolution, asked me to join him on this research team. Things sort of grew from there, from writing essays, to curating exhibitions, and finally we felt like it was time for us to do something different from what we were doing at our previous offices. That became the beginning of HAS design and research.

Photo: Kulthida Songkittipakdee

In a nutshell, HAS is us looking back at the architecture of our own home countries, studying and finding out more stories about contemporary architecture in Thailand, and Southeast Asia. We’re expanding our interest in other directions as well.

art4d: What made you become interested in the architecture of Southeast Asia?

KS: When Jenchieh began his study, he asked me a lot of questions. For some of the questions, I didn’t have an answer to even though I’m Thai. He even has a fuller grasp on Thailand’s architecture compared to me. I think it’s because with my educational background, I never really learned much about the architecture of Southeast Asia. Most of the stuff I learned was from the Western body of knowledge. When I worked in those overseas offices, no one really talked about how we could incorporate Thai locality to a project, because most people were more interested in trends from Singapore and Japan.

So I started to look up the history of architecture in Thailand, beginning with the modern architecture period, and sort of put that together with the history of the country at that specific time period. I began to understand how buildings of a certain appearance originated, how the Western influences affected the architecture of this country, to this day. And I’m not just looking at Thailand, but other neighboring countries in this region, studying how things have evolved and developed.

Guangzhou Sanyuanli City Village I Photo courtesy of HAS design and research

Through our thoughts and analyses of these causes, influences and history, the foundation and framework of HAS design and research has gradually been formed. When you’re an architect, practicing in this industry as your full time job, you don’t really sit down and really think about what you’re doing every day or how the things you see around you originated. The inception of our projects often starts with us questioning the issues existing in the surrounding environment and using them in the design.

art4d: Would you mind sharing how you incorporate such an approach to your design?

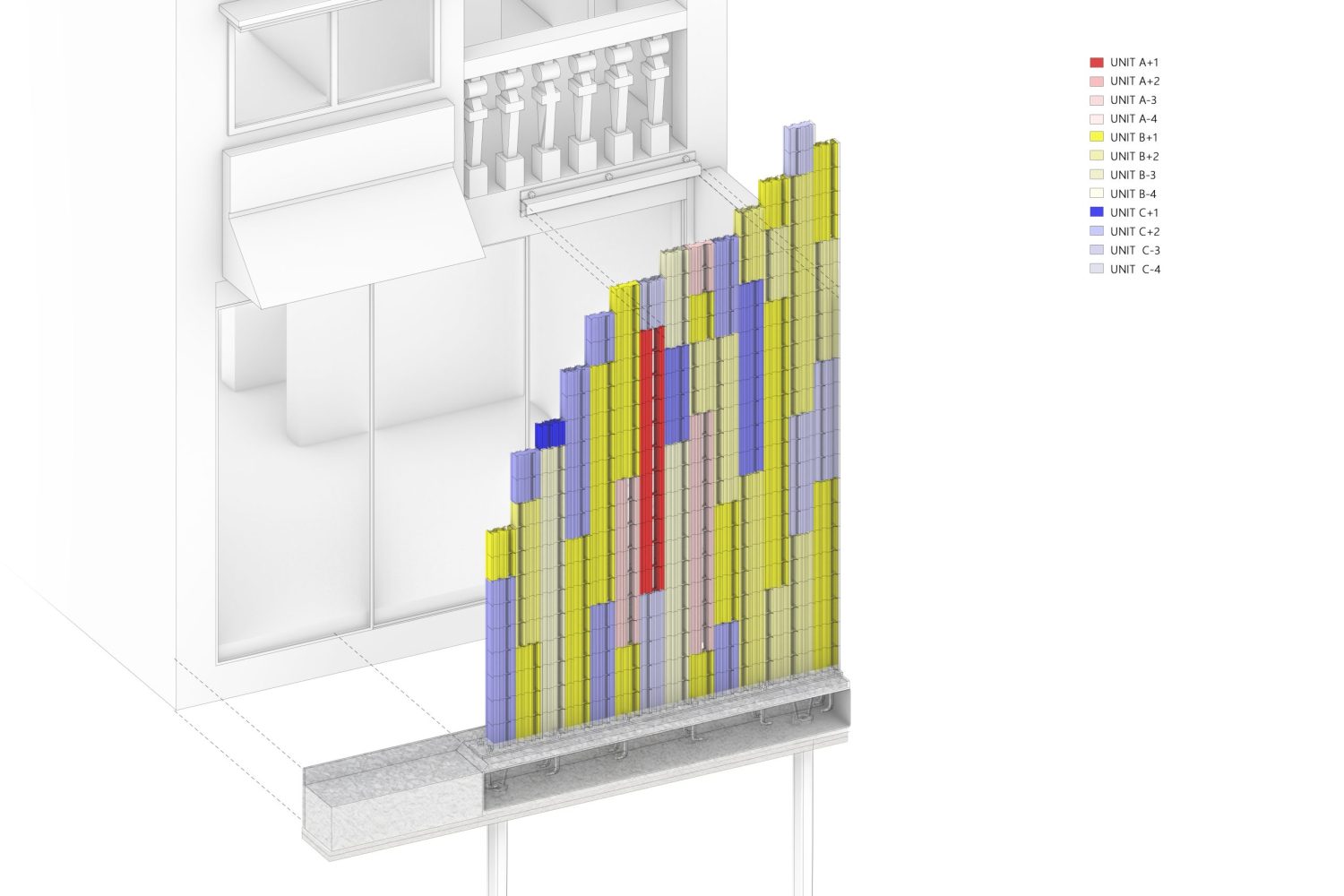

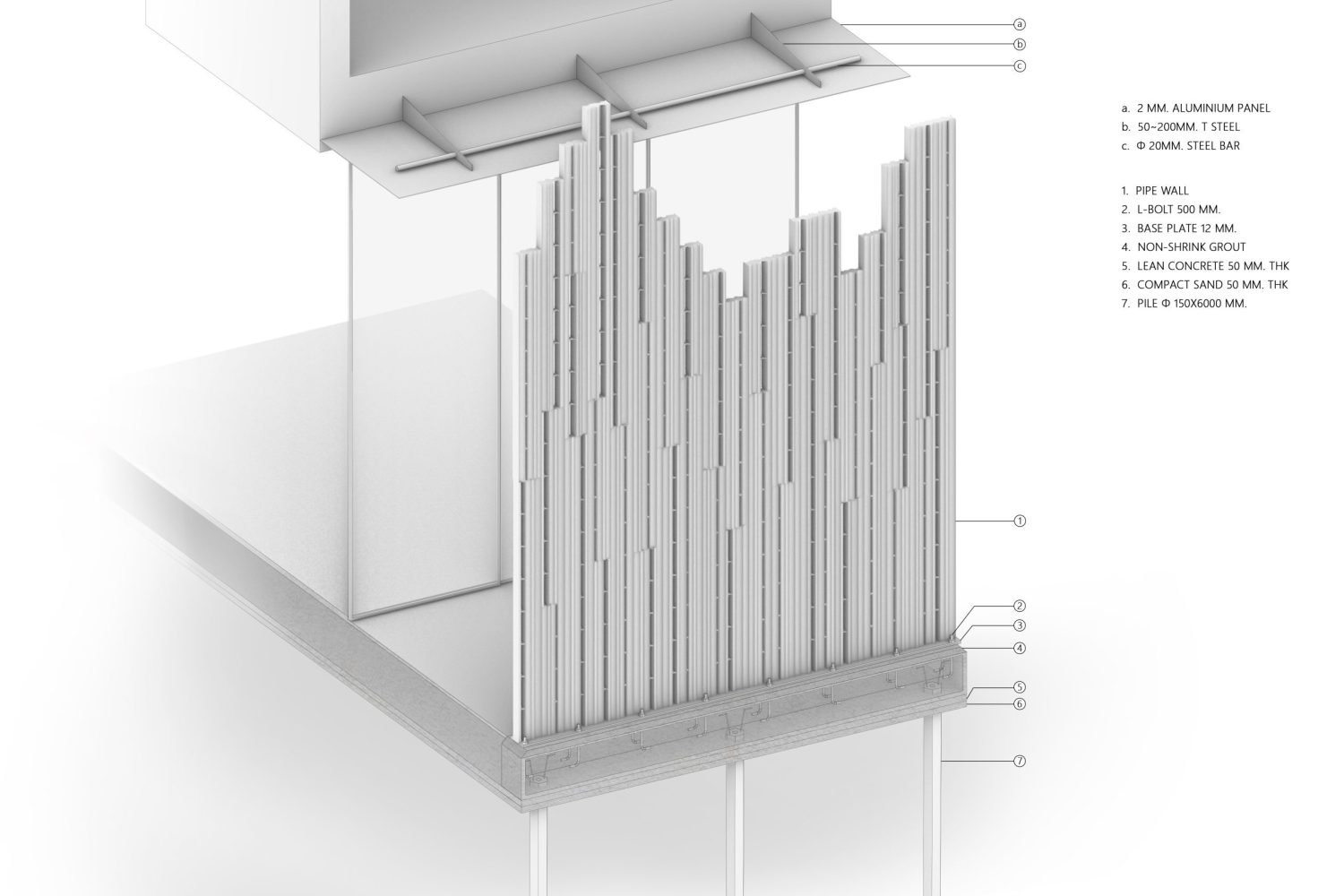

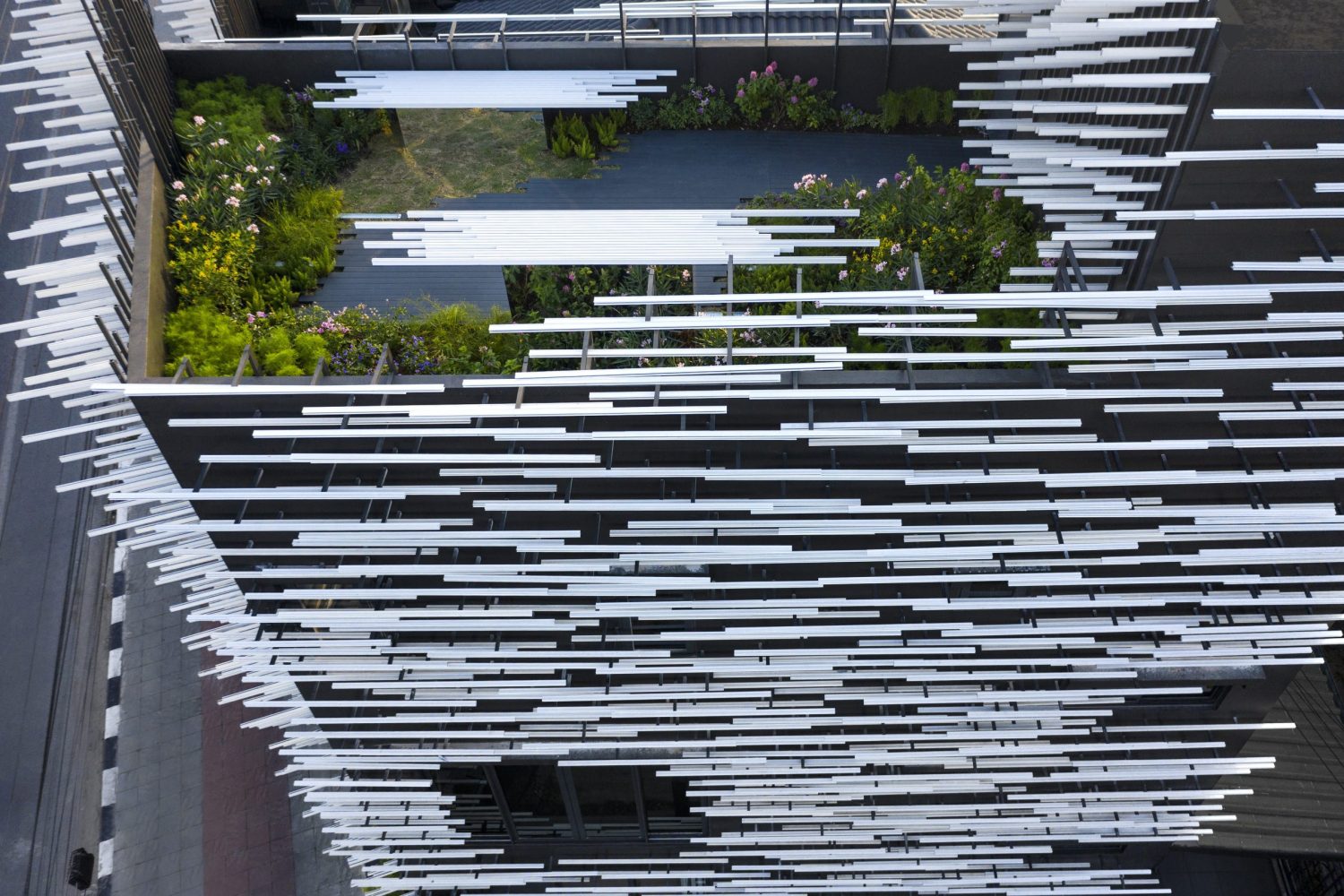

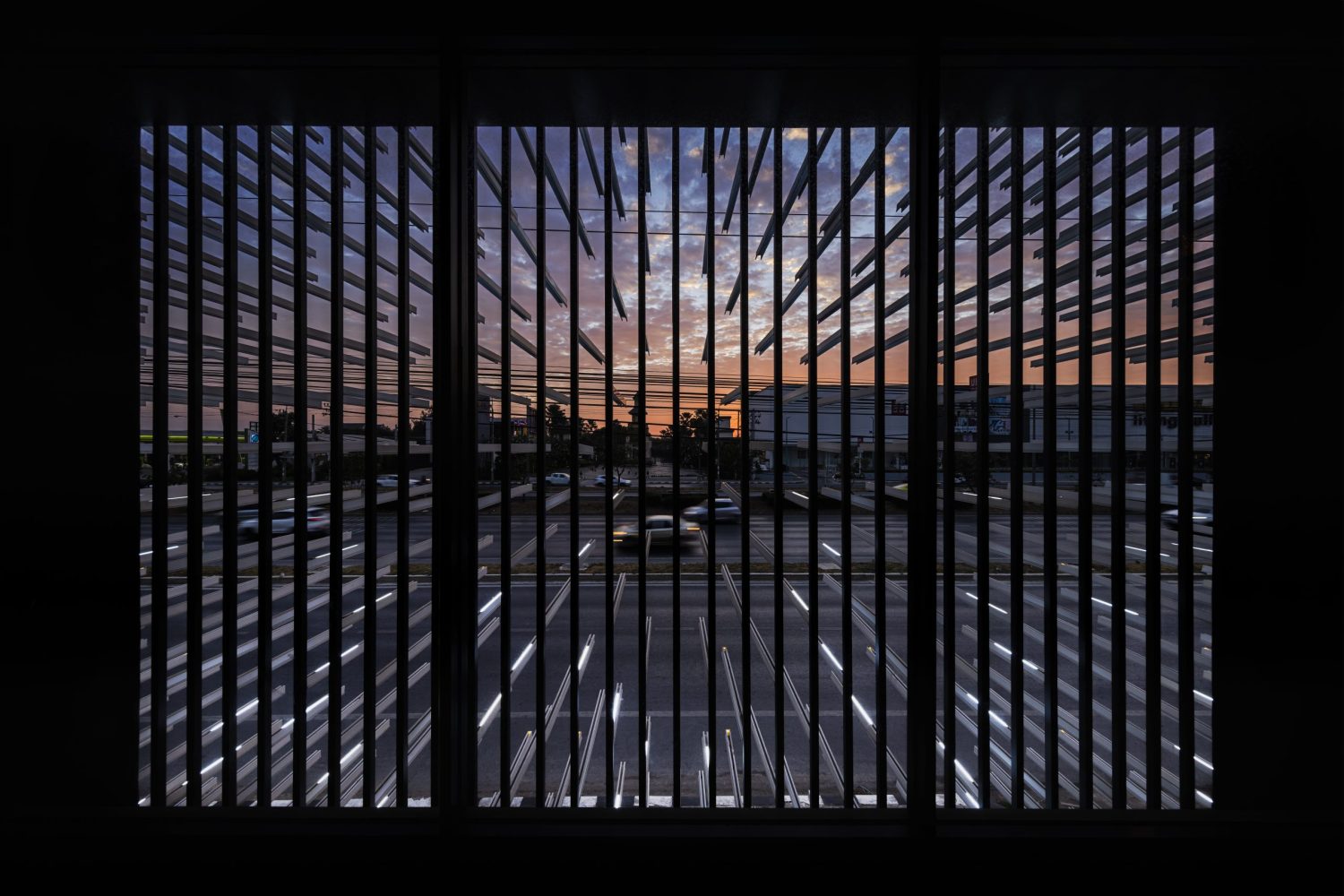

KS: The Phetkasem Artist Studio project was conceived from our interest in the context of townhouses or shophouses and the use of pipes or metal bars as the fence or façade. But these materials have never been used in other aspects. So we experimented on creating a metal fence but in a different application, by incorporating the fence as a part of the space instead of using it to create boundaries like how it would normally be used. The Museum of Modern Aluminum Thailand was developed from our interest in metal. We saw billboard signs on Ratchapruek Road in front of the building, and how on Ratchapruek Road, vehicles commute at such a high speed, and there are these billboards made of metal components everywhere but we didn’t see how this material would help make the those signs stand out. So we tried using metal as the main component, giving it the leading role of making the building distinctive and different. It’s bringing attention to things people neglect.

Phetkasem Artist Studio I Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

The detour stone road is like a traditional Thai alley I Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

One of our projects in China, The Glade Bookstore, isn’t just a normal bookstore, but a space where cultures are exchanged. We started off with how we could bring cultures into this space, and we did so by conveying the architectural characteristics of the vernacular architecture of Chongqing, which is the city where the project is located. The architectural elements of local ancient stilt houses are added to the interior decoration. But we didn’t use local materials in too much of a straightforward manner just to emulate an image of the past, but rather chose to use materials that would convey a connection to nature through the way the space is used. It’s more about a communication of the vernacular characteristics in the style that is more modern.

The Glade Bookstore I Photo: Yu Bai

Bookshelves used as space dividers, book display shelves and reading seats I Photo: Yu Bai

art4d: We’ve noticed the reinterpretation of locality in your work, how important do you think creating something new really is when there are people who choose to preserve locality in its original form because they fear that it will disappear?

KS: I look at it as a form of development. If we use old things like the way they were or have been used, there wouldn’t be new developments in architecture. Developing new typologies helps broaden people’s views of the world and imagination. And I like working on something that can generate new dialogues and make people’s view on different types of architecture change. The Botanic Meditation Centre is designed to be a meditation space inside a house’s private garden, but the owner wishes to share this space with other members within the community. It’s a conversion of a private space into a garden where outsiders are welcomed, creating a sense of participation within the community. Another project is Casa de Zanotta in Hefei, China, in which we transformed the numerous columns, which were considered the site’s limitation, into a design story. The design ended up turning the columns into a series of stone masses cut into seemingly randomized facets, referencing the natural surroundings of the mountainous region in which the site is located.

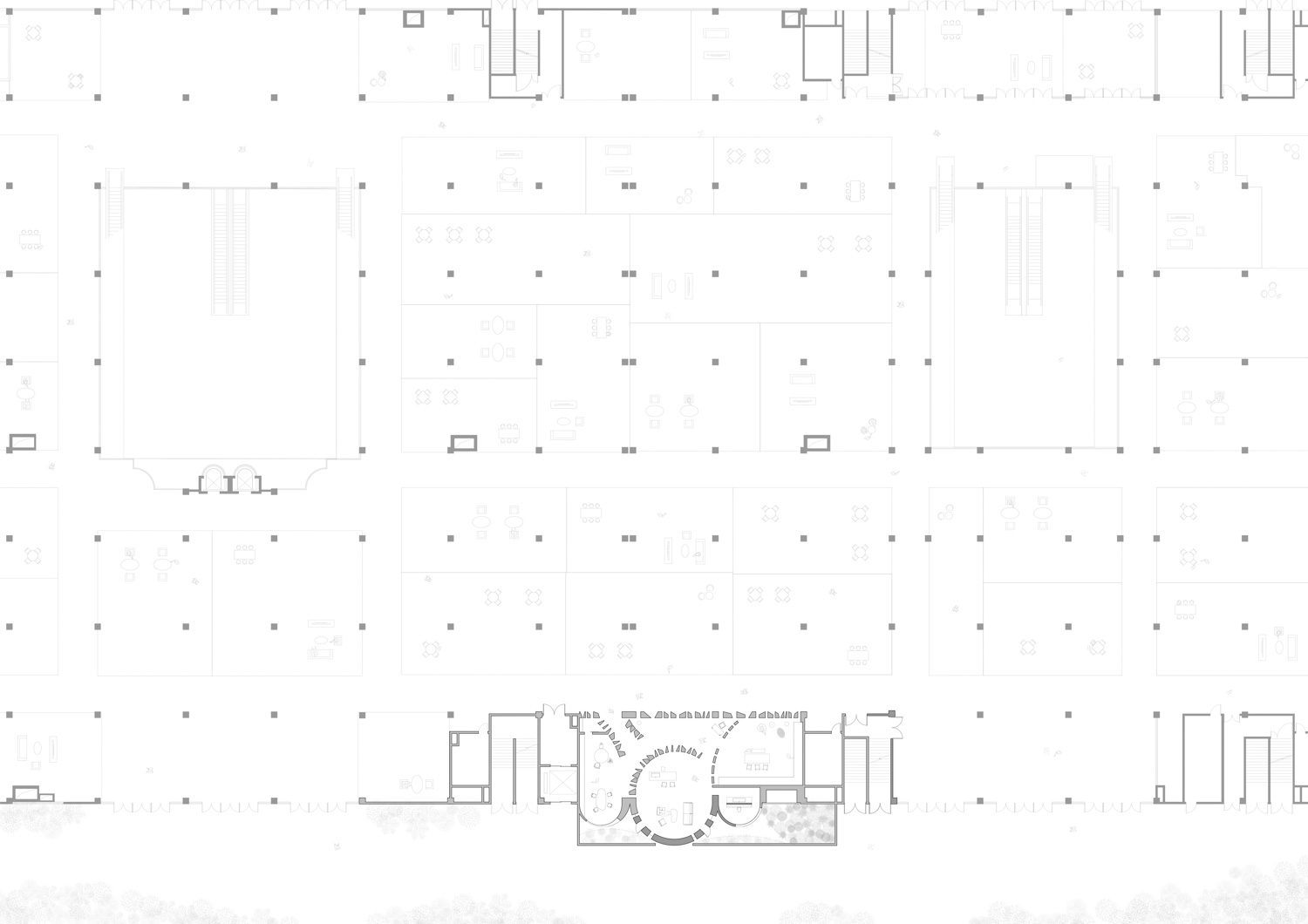

Casa de Zanotta Plan

Casa de Zanotta I Photo courtesy of HAS design and research

Casa de Zanotta I Photo courtesy of HAS design and research

art4d: Do you limit the scale of the projects you work on?

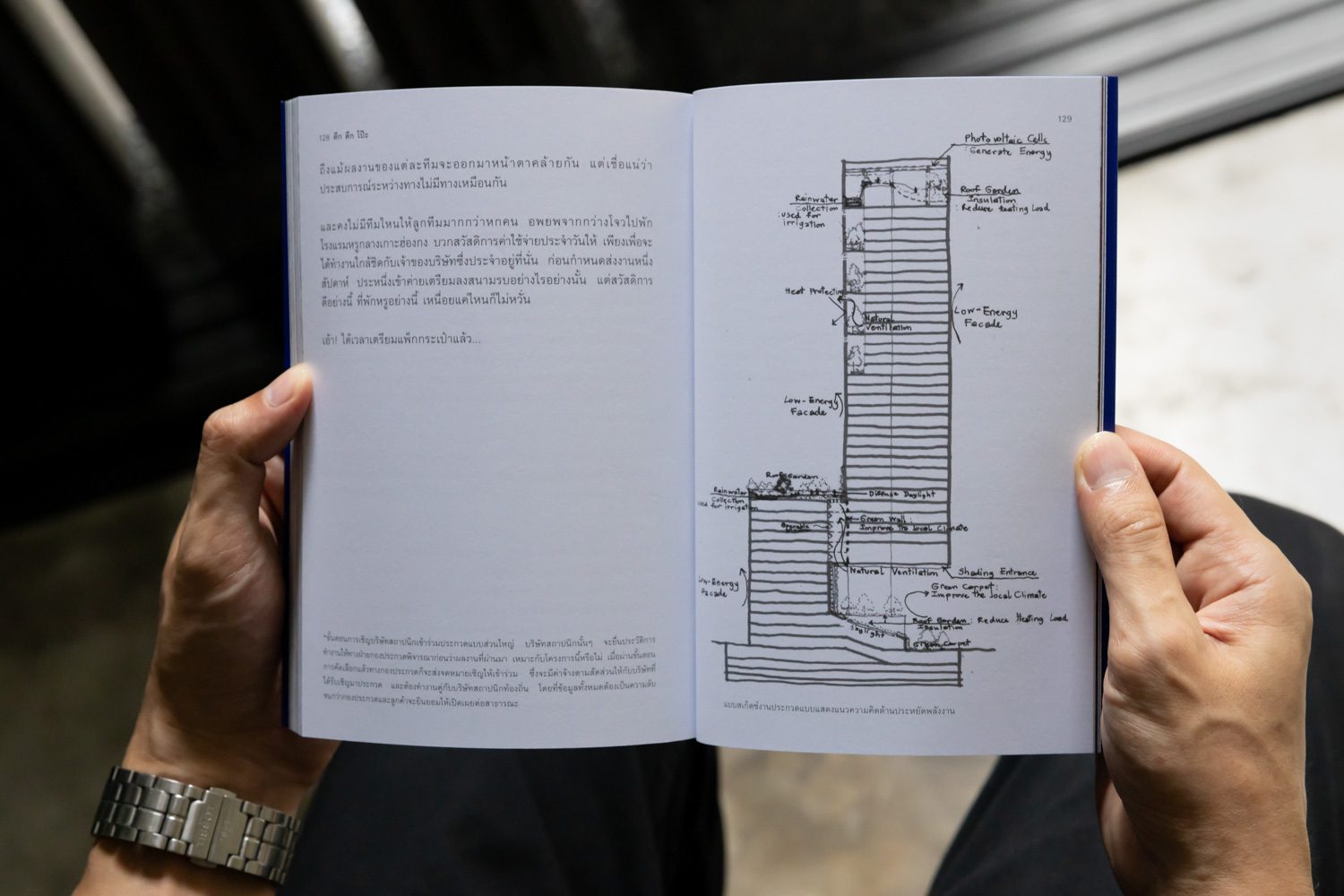

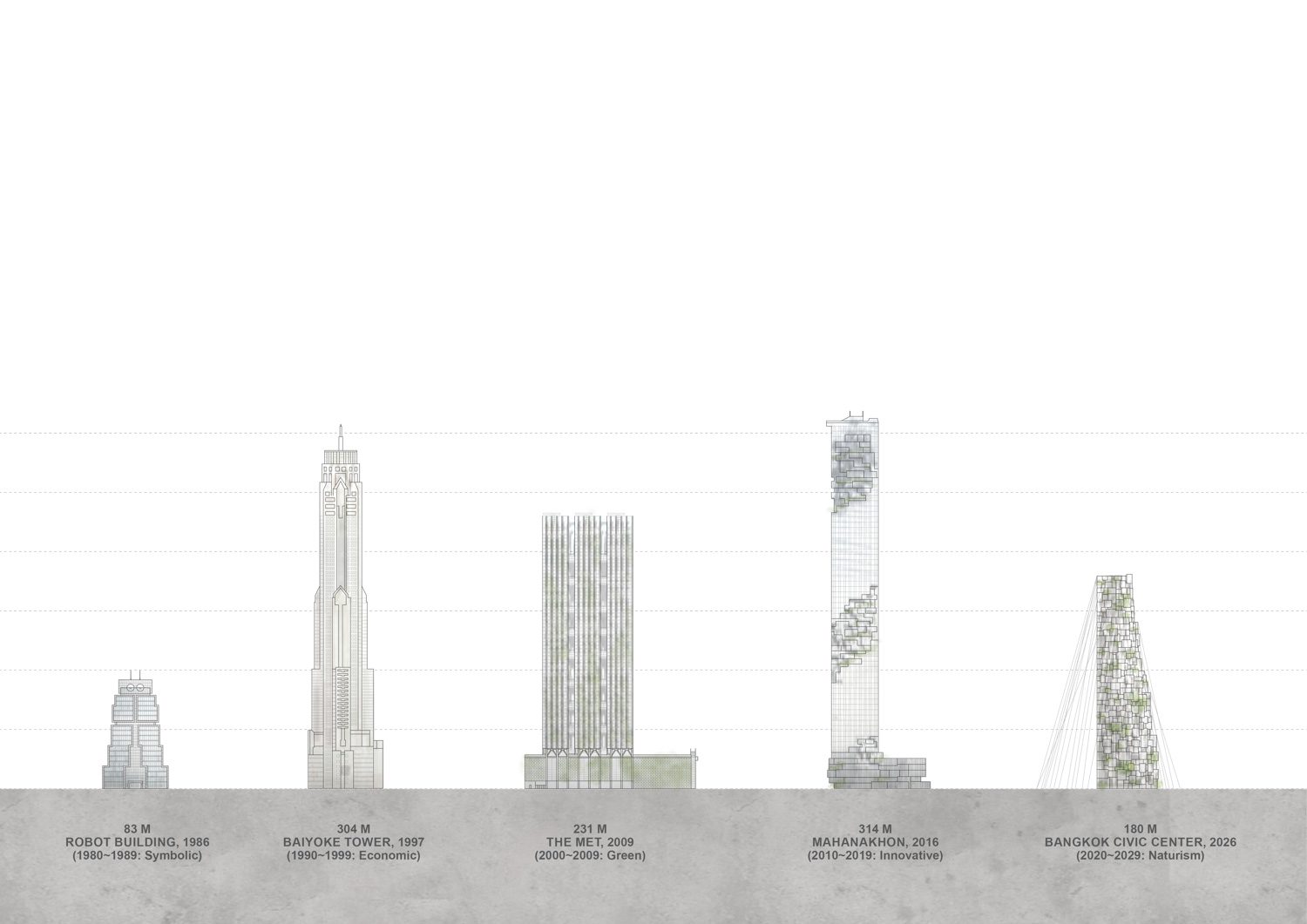

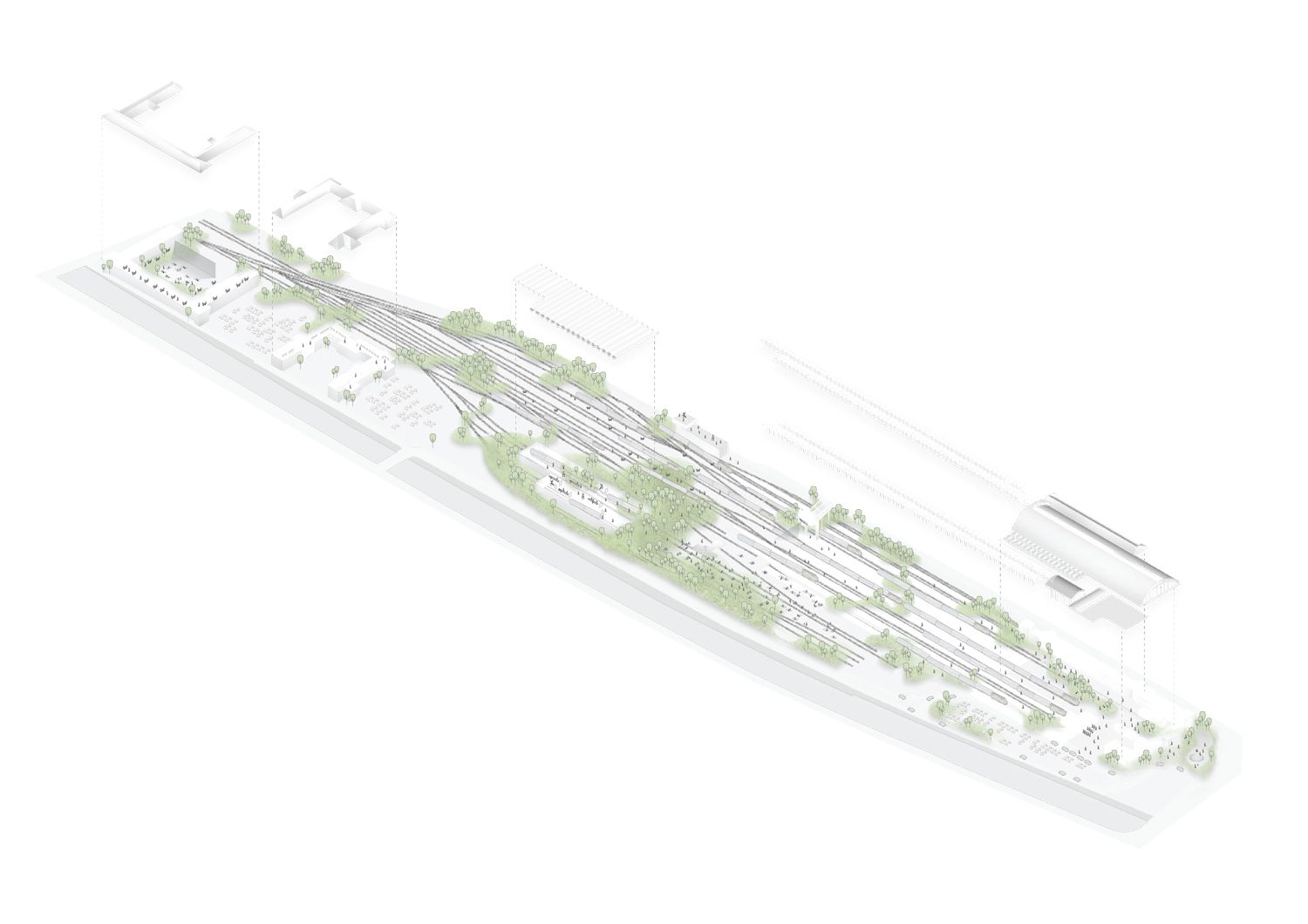

KS: Not at all. If a client were to come to us and ask us to design a high-rise building, we would do it. It’s just that the scale that we feel comfortable managing and doing right now is small to medium. But we have works that reflect our inspirations from the evolution of cities and we express them through HAS’s point of view, through our design that hopes to kick start new conversations for cities. For instance, Bangkok Civic Center is the project where we studied the evolution of high-rise buildings in Thailand. The building itself is designed to be a hub of public spaces, natural landscape, urban activities and transportation, which convey its status as a true urban civic center. Hua Lamphong Field is the project we helped imagine a dream vision of the 121 rai-land of Hua Lamphong Grand station and how the land can be used to create and accommodate new activities for the city, including how all the conserved old buildings in the property can developed to generate the best and most sustainable benefits for people in the city.

The transformation of urban issues into Bangkok landmarks in the past 40 years

Axonometric diagram shows activities and greenery in site

Train Restaurant I Photo courtesy of HAS design and research

Train Station Lobby as a Botanical Garden I Photo courtesy of HAS design and research

art4d: What makes you interested in taking so many roles, from being a writer to a curator?

KS: I like to look for new opportunities and whenever I’m given an opportunity, I will do it to the best of my ability. In terms of writing, I’ve always liked to write since I was a kid. I started taking writing seriously when I was living abroad. There wasn’t any social network platform for me to post anything and overseas calls were too expensive, so I would write. I would keep a journal of what I had learned, that I wanted to share with others. I started writing articles for art4d and then wrote a book where I tell my stories and experiences of being an architect working abroad.

Photo: Ketsiree Wongwan

Architect is still my main profession. If I have free time, I will write things that I find interesting for magazines. There was also the time when I started the research on contemporary architecture in Southeast Asia when I began to write something that was more academic. I was invited to be a special editor for a Taiwanese publication called Taiwan Architecture (TA). It’s an issue that features contemporary architecture in Thailand. I was given a chance to curate an exhibition about Thailand’s contemporary architecture in Shanghai. It was a small exhibition that took place at a venue in the city center and it was later expanded into a larger-scale exhibition, which was organized in Guangzhou. Since then, I have been invited to be a special editor for several other Chinese architectural publications.

Photo: Kulthida Songkittipakdee

art4d: Have these roles supported your role as an architect?

KS: Significantly. I think they help me contemplate, think and analyze the origins of the architecture I have created. Otherwise, I think I would feel like I do things without having a really clear direction or goal. These roles help me develop and maintain my critical thinking.

art4d: From all your experiences so far, do you think you can give some sort of conclusion or definition of good architecture?

KS: These days, I’ve seen this trend where architects submit their works for competitions. Winning a competition gives a work a credential. But I do question whether awards are ultimately a true indication of a good work of architecture. I think it depends on each person’s attitude and point of view. One may view a certain thing as good while another person may think otherwise. The definition of good architecture should be about an architect’s intention and what kind of conversation they want their work to bring to a city, and whether their work can generate new ideas, bring greater benefits to users and inspire new imaginations for those who see or experience it. If architects don’t have that type of thinking, I feel that architecture will end up being merely a physical object created to meet a client’s needs, and nothing more.