THE EXHIBITION ‘TROPICAL MODERNISM: ARCHITECTURE AND INDEPENDENCE’ SHOWCASES THE HISTORICAL ROLES OF TROPICAL ARCHITECTURE WHICH WAS ONCE INTEGRATED WITH MODERNISM

TEXT: PARK LERTCHANYAKUL

PHOTO COURTESY OF VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

As natives born and bred in a tropical climate, when we speak of tropical architecture, the discussion is hardly an abstract or distant one—it is, quite literally, the setting of our everyday lives. Nevertheless, for most British people, the notion of a tropical climate is an utter departure from the familiar drizzle and chill of England. In an era where modernist architecture was at its zenith, Britain’s expansive colonial footprint across tropical territories catalyzed a unique architectural synthesis. This amalgamation of sleek modernist principles with the vernacular of tropical regions gave rise to what we now recognize as tropical modernism. The exhibition ‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence’ cleverly walks us through this narrative arc—from the early days of these architectural experiments, through the ideological evolution during the decline of colonialism, and into the contemporary adaptations of the present day.

The entrance to the exhibition from the central hall of the V&A

The exhibition unfolds across four distinct sections, each marked by partition walls punctuated with window-like apertures and framed by structures akin to air vents at both the upper and lower parts of the walls. These architectural gestures are quintessential to tropical modernism, cleverly echoing the airiness and openness that define the style. This thoughtful arrangement transports visitors, giving the immediate and immersive impression of entering a building that not only displays but also embodies the very essence of the era in which it originated.

The first room of the exhibition welcomes viewers with walls and tables painted a vivid orange, setting the stage for an exploration into the origins of tropical modernism in West Africa post-World War II. This architectural philosophy arose from Britain’s colonial efforts to refashion its overseas territories to reflect the modernization of the homeland. Following the war, Britain poured substantial funds from post-war resources into the vast, unoccupied spaces of West Africa. This investment, combined with hefty financial support, transformed the region into a kind of sprawling laboratory. Here, British architects were given free rein to experiment with modern architectural concepts, unbound by the urban constraints they would typically face back in Britain. This era also provided them a rare chance to engage in large-scale building projects, an opportunity not readily available to every architect.

The first section of the exhibition tells the story of West African countries

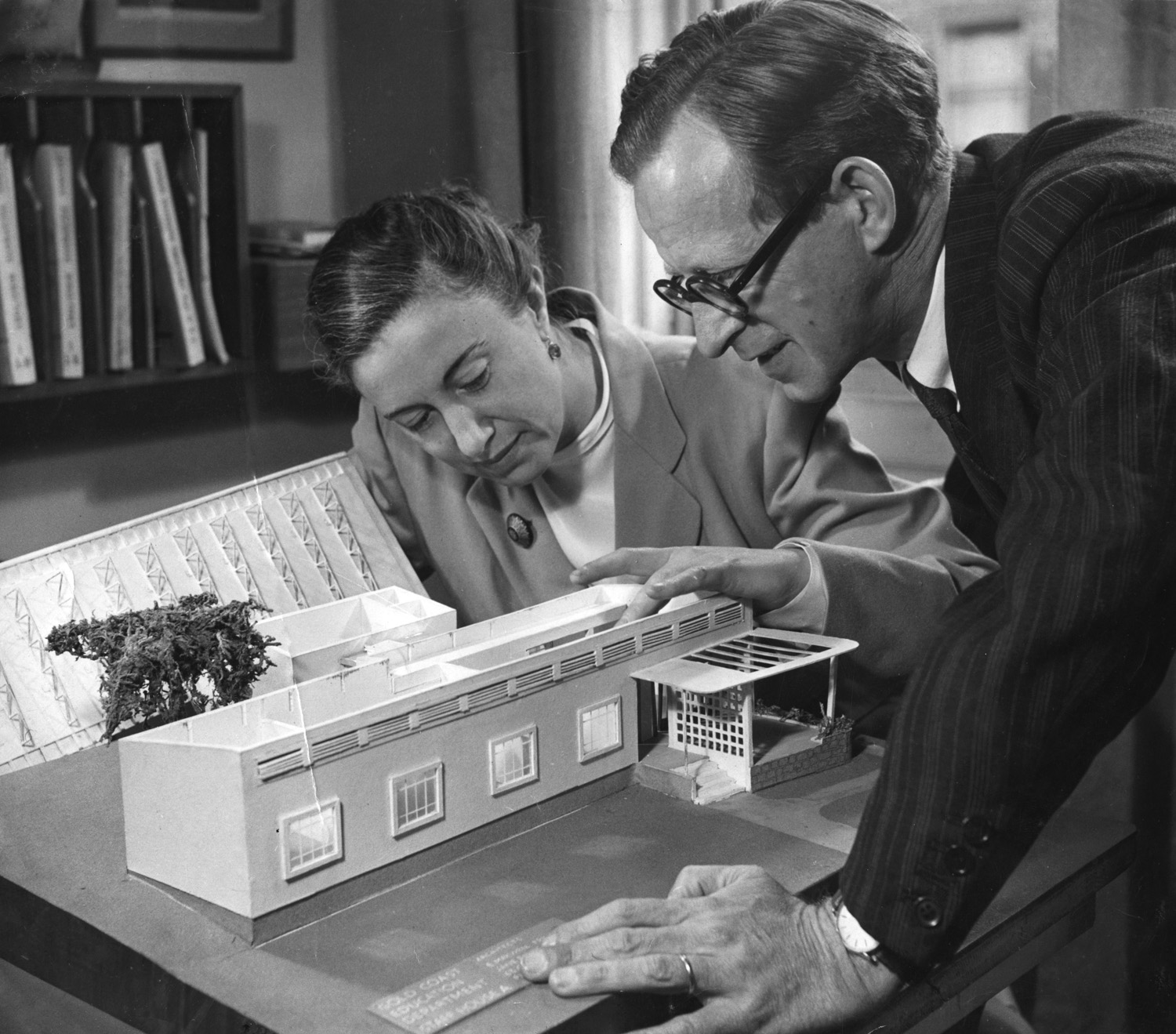

In 1944, Maxwell Fry, stationed on the Gold Coast—now Ghana—and Jane Drew, proposed a project to design and build a new city. They adapted European modernist architectural principles to the tropical climate, incorporating modern design technologies that took the local weather into consideration, such as cross-ventilation by designing elongated, slender buildings with deep verandas and expansive roofs.

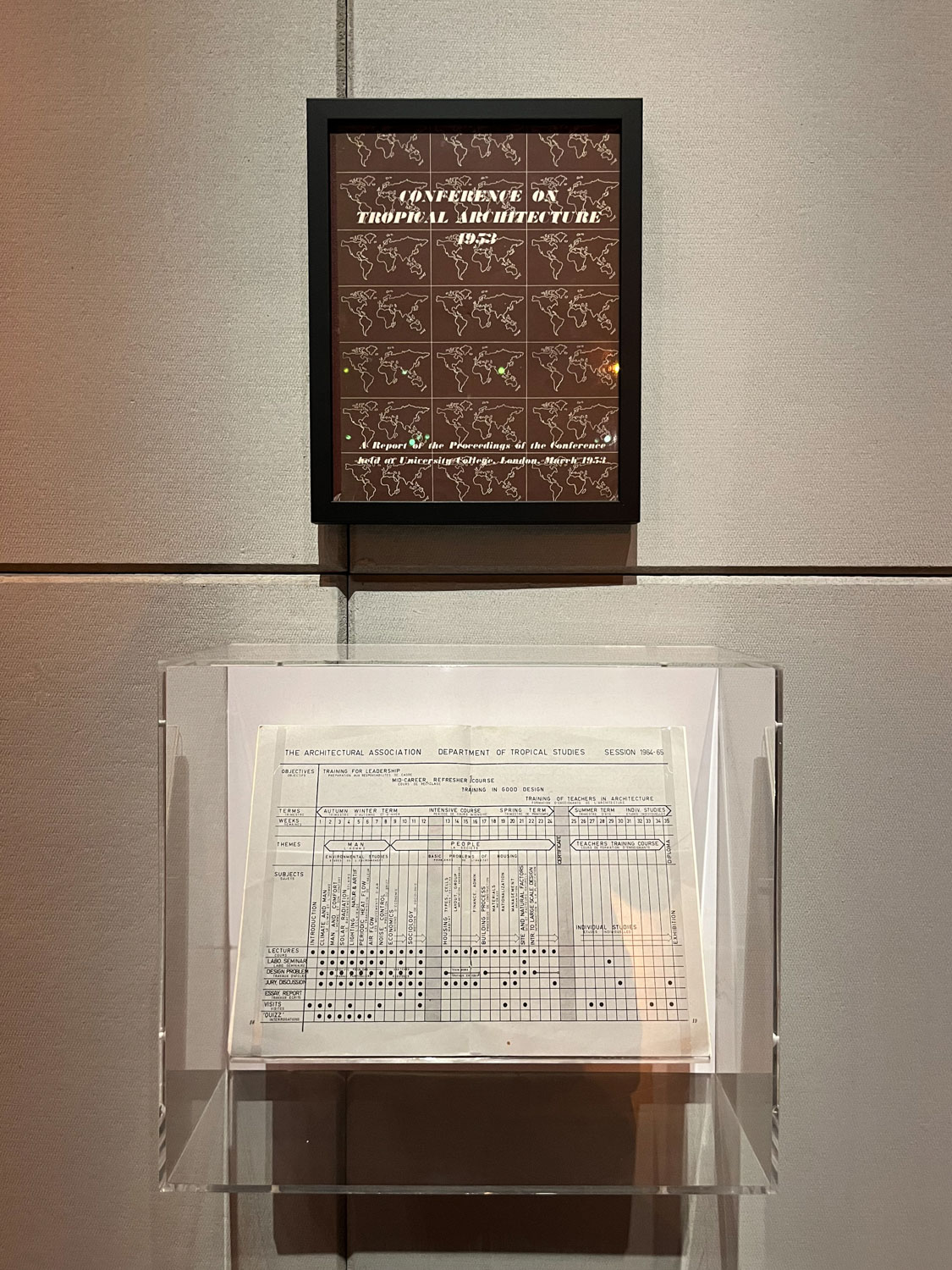

The publication of the Conference of tropical architecture and the course syllabus for the tropical studies department at the Architectural Association, School of Architecture | Photo: Park Lertchanyakul

Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew exemplified a distinctly colonial outlook towards indigenous architecture, demonstrating a notable disregard for the local architectural vernacular. They even asserted that indigenous architecture was nonexistent on the Gold Coast, compelling them to conceive an architectural style suitable for West Africa on their own. The exhibition showcases a plethora of articles and books penned by them that explore the architecture of West Africa and tropical regions. There is a compiled volume on tropical architecture that exclusively features designs by British and European architects, conspicuously omitting any contributions from African architects. Despite the presence of numerous Ghanaian architects collaborating with the British during this period, their work and names were never mentioned in these publications and have only begun to receive recognition in recent years.

Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry with a model of one of their many buildings for the Gold Coast, 1945 | Photo courtesy of RIBA

Fry and Drew incorporated the form of the traditional Ashanti stool, considered a sacred household object among the people of the Gold Coast, into the design of the brise soleil in the background.

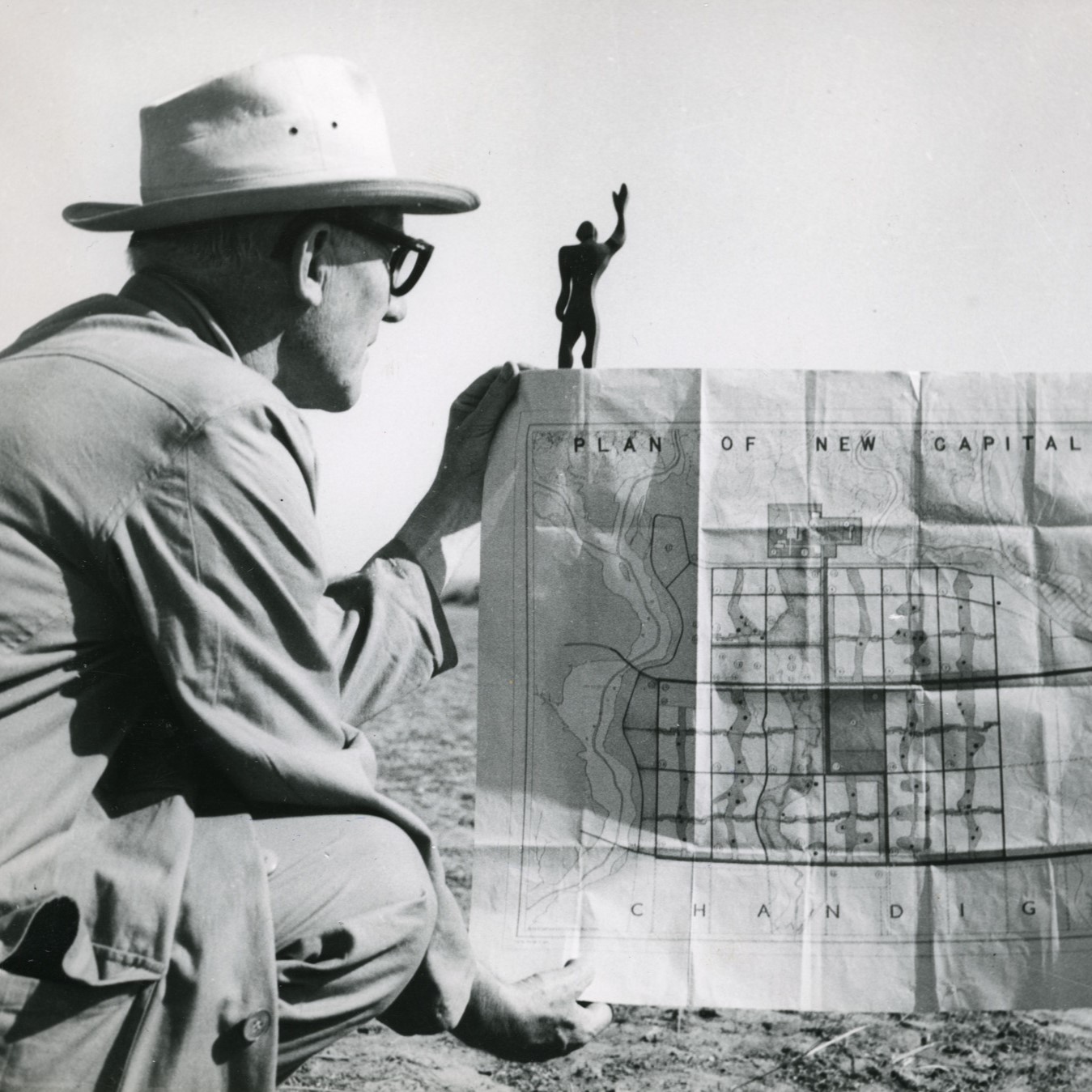

The second segment of the exhibition, distinguished by its yellow walls, transports viewers to India in 1947. Emerging from the shadows of colonial rule, India was on the brink of establishing a new capital in Punjab to serve as both an administrative hub and a refuge for those displaced by the partition with Pakistan. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru spearheaded the creation of Chandigarh, a city envisioned as a beacon of modernity intended to unify and propel India into a forward-looking era. Nehru championed modern architecture as a universal language, unshackled from the constraints of power or colonial legacies, aligning with his aspiration for India as a secular state and reflecting the nation’s progressive thinking.

Chandigarh is celebrated as the world’s inaugural modernist city. Attracted by their innovative work in Africa, Nehru enlisted Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry for this pioneering project, and they brought on board Le Corbusier, a luminary of modern architecture. Nehru envisioned Chandigarh as a ‘living school,’ where these European titans of architecture would mentor a cadre of budding Indian architects. This initiative was designed not just to educate but to permeate India with modern architectural tenets, thereby fostering nationwide development.

A 3D model of Chandigarh’s master plan | Photo: Park Lertchanyakul

Accompanying this are various architectural plans and models, including period-specific furniture. These elements are presented against a backdrop of sculptures depicting local Indian figures. Adjacent to these artistic representations are photographs and videos detailing the construction of Chandigarh. One striking video juxtaposes scenes from a drafting classroom filled with Indian students against the bustling construction site outside. Notably, the video emphasizes the reliance on manual labor over machinery due to the era’s low labor costs. A diverse workforce of Indians—men and women, young and old—was integral to the city’s construction. Visuals capture the traditional techniques used: bamboo scaffolds and handmade concrete molds illustrate the grassroots approach. The laborious process of concrete preparation involved manually mixing in pits, followed by the transfer in baskets, which female workers would carry on their heads to the scaffolding where more workers awaited at every level to pass the baskets hand-to-hand, transporting the concrete up to the heights of the buildings to be poured into large casting molds.

The second section of the exhibition

The exhibition’s concluding gallery displays the developments in architecture across both Ghana and India over time, with all featured works designed by architects from these nations.

The first section showcases a model of the Hall of Nations, designed by Indian architect Raj Rewal. Erected in 1972, this structure symbolized the celebration of India’s 25th year of independence. But as Hindu nationalism gained traction, the modern architectural ethos championed by Nehru was viewed as antithetical to religious beliefs and was demolished overnight in 2017.

The third section Front: Models and photographs of the Hall of Nations by Raj Rewal. Back: The exhibition dissecting the complex entanglement of politics and architecture in Ghana following its independence.

Across the Indian Ocean in Africa, Kwame Nkrumah, instrumental in leading Ghana to its independence in 1957, also advocated for modern architecture as a cornerstone of national progress. However, his governance veered towards authoritarianism, transforming Ghana into a single-party state and stifling political opposition. The consequences were swift—Nkrumah was overthrown, a statue erected in his honor was dismantled by his own people, and the modern architecture he had supported was left to decay.

The exhibition’s final part unfolds in a room dedicated to the documentary ‘Architecture and Power in West Africa.’ This poignant film elucidates the complicated interplay between political authority and architectural innovation in post-colonial Ghana. Newly designed school buildings featured the city’s central church spire dominating the skyline, visible from the school’s central court and entrance pathways. The documentary intersperses interviews and images of various buildings, concluding with an upbeat local song that invites one to dance.

The final section of the exhibition features a video documentary and interviews about tropical modernism in Ghana. The room includes a replica statue of Kwame Nkrumah, a nod to his original statue, which was destroyed by the public following his overthrow in a coup.

The term ‘tropical modernism’ feels too narrow to capture the full spectrum of architecture on display in this exhibition. These designs do not merely respond to climatic conditions; they are deeply informed by factors such as culture, social dynamics, and politics. This multifaceted nature brings to mind the closure of the tropical architecture department at the Architectural Association, School of Architecture in 1971. Helmed by Maxwell Fry, the department had thrived for 17 years, only to be rendered redundant with the rise of air conditioning, which eliminated the need for architecture in the tropics to be designed specifically with ventilation and airflow.

The exhibition ‘Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence’ is currently available for viewing at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England, from March 2 to September 22, 2024.