A ROCKING ROAD TO THE MOON, THE LATEST EXHIBITION BY TADA HENGSAPKUL THAT TAKES US ON AN EXPLORATION OF DREAMS, INEQUALITY, AND THE ROAD TO THE FUTURE THAT HAS YET TO ARRIVE

TEXT: PRAPAN JANGKITCHAI

PHOTO: PREECHA PATTARAUMPORNCHAI

(For Thai, press here)

“Standing on the road, one fights alone for a dream, Tossed like a wisp of straw carried far by the wind.” – Road to Dreams

These lines from Road to Dreams lend their spirit to the title of ‘A ROCKING ROAD TO THE MOON – Standing on the Road, One Fights Alone for a Dream…,’ a new photographic installation by Tada Hengsapkul, curated by Surawit Boonjoo. The exhibition, on view from 17 May to 13 July 2025 at HOP PHOTO GALLERY, is inspired by a song by Takkatan Chollada. The lyrics give voice to the hardships faced by migrant workers from the Isan region; those who stake their futures on an uncertain path, leaving the warmth of home behind to toil in Bangkok and send back what they can to support their families.

Year after year, waves of laborers from Isan have flowed into the “city that never sleeps…” along Mittraphap Road, a road born of American aid, funded and built under technical guidance from the United States government. It was Thailand’s first highway constructed to modern standards and the nation’s first paved with asphaltic concrete. Inaugurated in 1957, Mittraphap Road carried with it both promise and expectation: that it would help lift Isan from scarcity into the folds of the modern world1, while also serving the military strategy of connecting Bangkok to American bases and the country’s borderlands2. This very road is the starting point for Tada’s latest work.

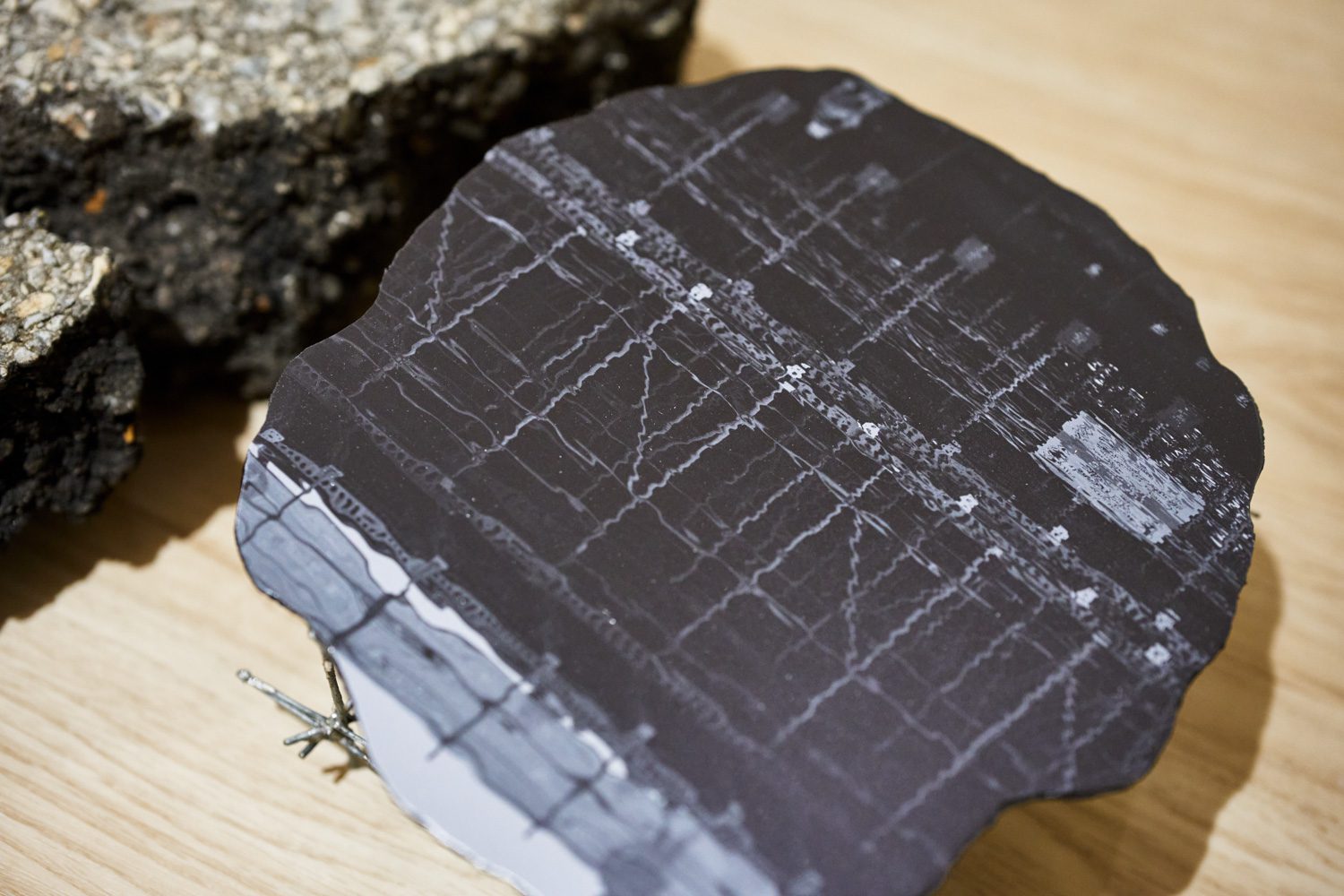

In contrast to YOU LEAD ME DOWN, TO THE OCEAN, where artist and curator transformed the gallery into the depths of an ocean floor, immersing viewers in a submerged world of drifting, abandoned objects waiting to be felt and understood, Tada and Surawit, in this exhibition, have reimagined the space as a vast, open expanse bisected by a short stretch of road. Here, a fragment of Mittraphap Road has been laid down, but Tada’s Mittraphap is no flawless highway. There’s no smooth, enduring promise of prosperity, stability, and progress for Isan, nor the polished gift of friendship once exchanged between Thailand and the United States in the Cold War years. Instead, the road that visitors stand upon and cross back and forth is fractured, rough, and cobbled together from remnants of old asphalt. These sculptural fragments were cast from potholes near the artist’s hometown in Nakhon Ratchasima. Some hollows hold pools of still water that mirror the façades of government buildings, such as the Parliament House, while beneath, lattices of interwoven aluminum rods adjust the height and keep the water’s surface level with the road’s varying thickness. Together, these elements scatter across the floor to form an oblique slice of roadway; an uneven marker inviting viewers to step across, marking the first passage into the space within.

A road is one of the most vital forms of infrastructure. It connects and binds distant places, stitching them into a single line of passage. In one sense, it becomes a symbol of conquest, claiming the land it crosses and carrying with it both the intangible; power, culture, hope, dreams, and the tangible, such as goods, resources, and people moving from one place to another. Road building is inseparable from ideas of development and advancement. A road is also deeply connected to time. It does more than compress space and shorten distances; it accelerates time itself, bridging the past, the present, and the future. The infrastructure built long ago shapes the present and the years that follow, just as the roads planned for the future can change the conditions of today3. A perfect road in the present lays the groundwork for what is yet to come. It helps move time forward, carrying people toward a better tomorrow. It stands as both a sign and a promise of dreams and the hope for a better life ahead.

A road left cracked and crumbling is a future held back, a stretch of time that cannot move forward. In his process, Tada works like an archaeologist, digging into the layers beneath the surface to find how the road’s construction and repairs failed to meet proper standards. He uncovers the use of poor materials and careless oversight that allow overloaded trucks to pass again and again, wearing the surface down before its time. What remains is a cycle of constant repairs that consume budgets which could have paved the way toward real progress. From this nearly seventy-year span of wasted time, Tada shapes broken asphalt and rainwater pools into forms that ask viewers to reflect on development that appears to shift and move yet stays rooted in place. Each layer of road becomes a slice of frozen time, stacked one atop another like sediment, accumulating upward instead of stretching forward into a clear path for the future.

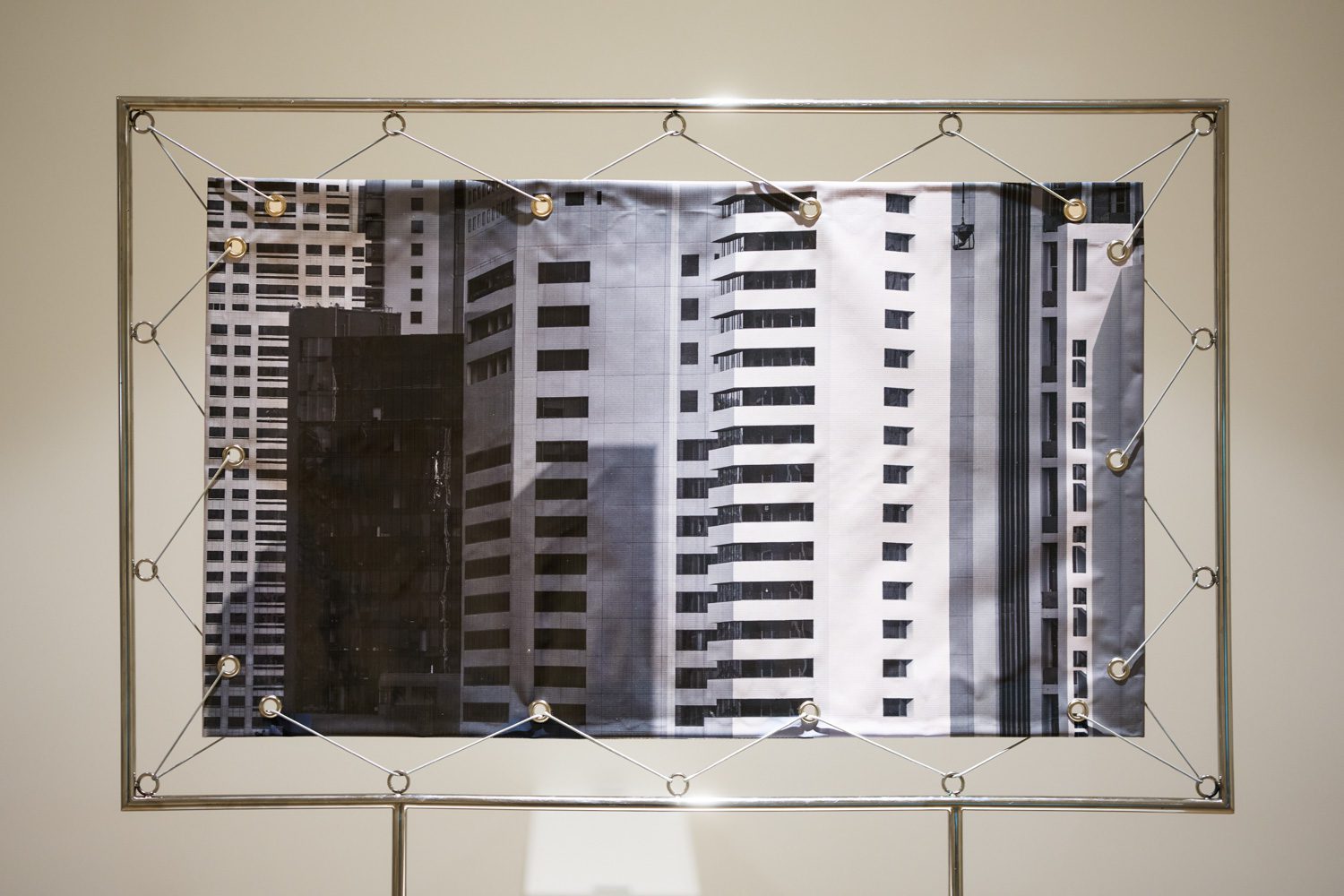

Beside the road stands a set of three barriers, swaying gently back and forth. Each barrier has a photograph mounted on top. They are images of high-rise condominiums and office towers packed tightly together, shot from the rooftop garden of Samyan Mitrtown Building in the heart of the city of Bangkok. These towering buildings, symbols of progress and a promised future, appear here as weightless illusions, untouchable and adrift, their foundations unsteady and shifting. The barriers, which should stand firm and solid, instead feel insubstantial, just like the broken fragments of road they echo. Their constant, wavering motion hints at movement yet, leads nowhere.

Beyond the road, a black-and-white video plays, showing roadside landscapes drifting by with the motion of cars along Mittraphap Road. Using a slit-scan technique, the artist distorts the footage so that vehicles and scenery bend out of shape, some stretches pulled and exaggerated to the point of unreality. This warped monochrome landscape becomes a spectral echo of government promises; an ever-repeating illusion that life will be elevated and improved. At times, the video shows cars creeping forward, their wheels rolling over scattered fragments and potholes just like those in the gallery, as if these vehicles are driving along this same broken road. They inch along, only to circle back and begin again at the same point, endlessly looping. They shift, they move, but they never truly arrive.

Tada has not returned simply to scratch at the surface or lightly prod the ruling class. Instead, he strikes with full force. It’s a slap to the face, a punch to the gut, laying bare their failures and deceptions through the very fragments of broken road that stand as evidence of their institutional decay. At the same time, he compels viewers to confront the stark reality of the present political condition: our time has been frozen, held back, made to shift and stir under the guise of investment and progress, yet never truly allowed to move forward. The chunks of asphalt and pools of water that visitors step over and across are seventy years of our collective time, held captive. This condition is underscored by the exhibition’s title, drawn from the hook of the song “Standing on the Road, One Fights Alone for a Dream….” Released in 2007, more than eighteen years have passed since then, yet the quality of life for ordinary Thais remains much the same. Security of life and property is still far from guaranteed, because the very foundations of our infrastructure, along with our freedoms and rights, remain pinned down and fastened in place by the elite. And so our lives remain ‘tossed like a wisp of straw,’ fragile, adrift, unanchored.

From Takkatan Chollada’s song then, to Tada’s exhibition now, our shared future continues to be held hostage in the name of hollow development. Until power truly belongs to the people; until the sky turns gold and clear, are we to live like this still?

_

1 Editorial Team, Sinlapa Watthanatham (Art & Culture), “‘Sut Banthat–Jen Chob Thit’ to ‘Mittraphap Road’: Cutting Bangkok–Korat Travel Time from 10 to 3 Hours,” accessed 13 June 2025, available at: https://www.silpa-mag.com/history/article_25179

2 Pracha Suveeranont, Monotype: Fevered Bodies and the Cold War (Part 1), accessed 13 June 2025, available at: https://www.matichon.co.th/weekly/column/article_43064`

3 Jiraporn Laojaroenwong, “Infrastructure,” in 100 Contemporary Anthropological Concepts, edited by Naruepon Duangwiset and Wisut Wetchawaraporn (Bangkok: Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre (Public Organization), p. 206).