A BOOK BY HONG KONG ARCHITECT PHILIP FUNG, REVEALING THE DEFINITION OF ‘EMPTINESS’ AS A SPACE THAT ENDLESSLY ALLOWS CREATIVITY TO FILL IT

TEXT & PHOTO: PIBHU DEVAKUL NA AYUDHYA

(For Thai, press here)

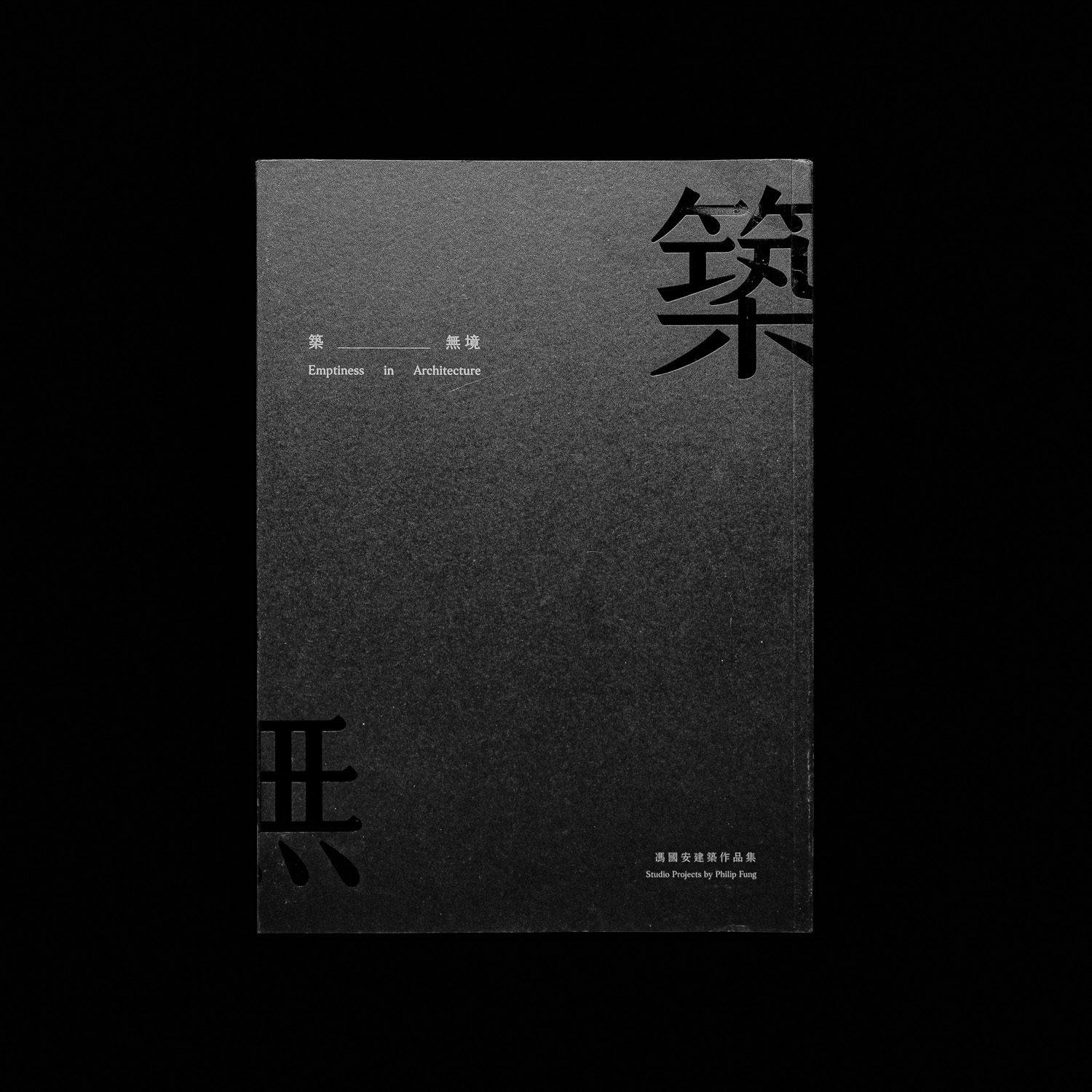

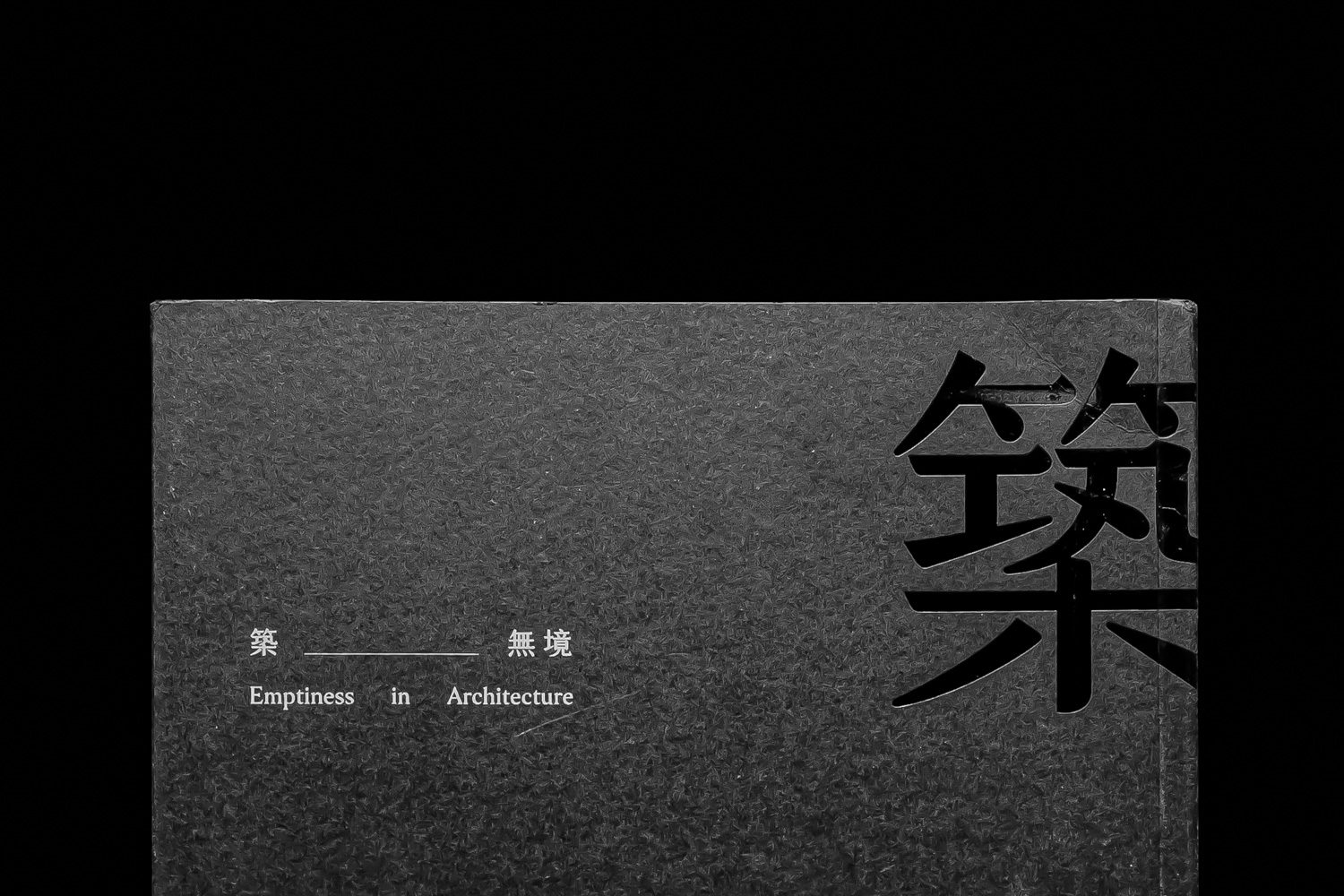

Emptiness in Architecture: Studio Projects by Philip Fung

馮國安 (Philip Fung)

田園城市文化事業有限公司, 2022 (初版) GARDEN CITY PUBLISHING LTD. ,2022 (first edition)

10.24 inch × 10.24 inch

128 Pages

ISBN 978‐626‐95273‐5‐9

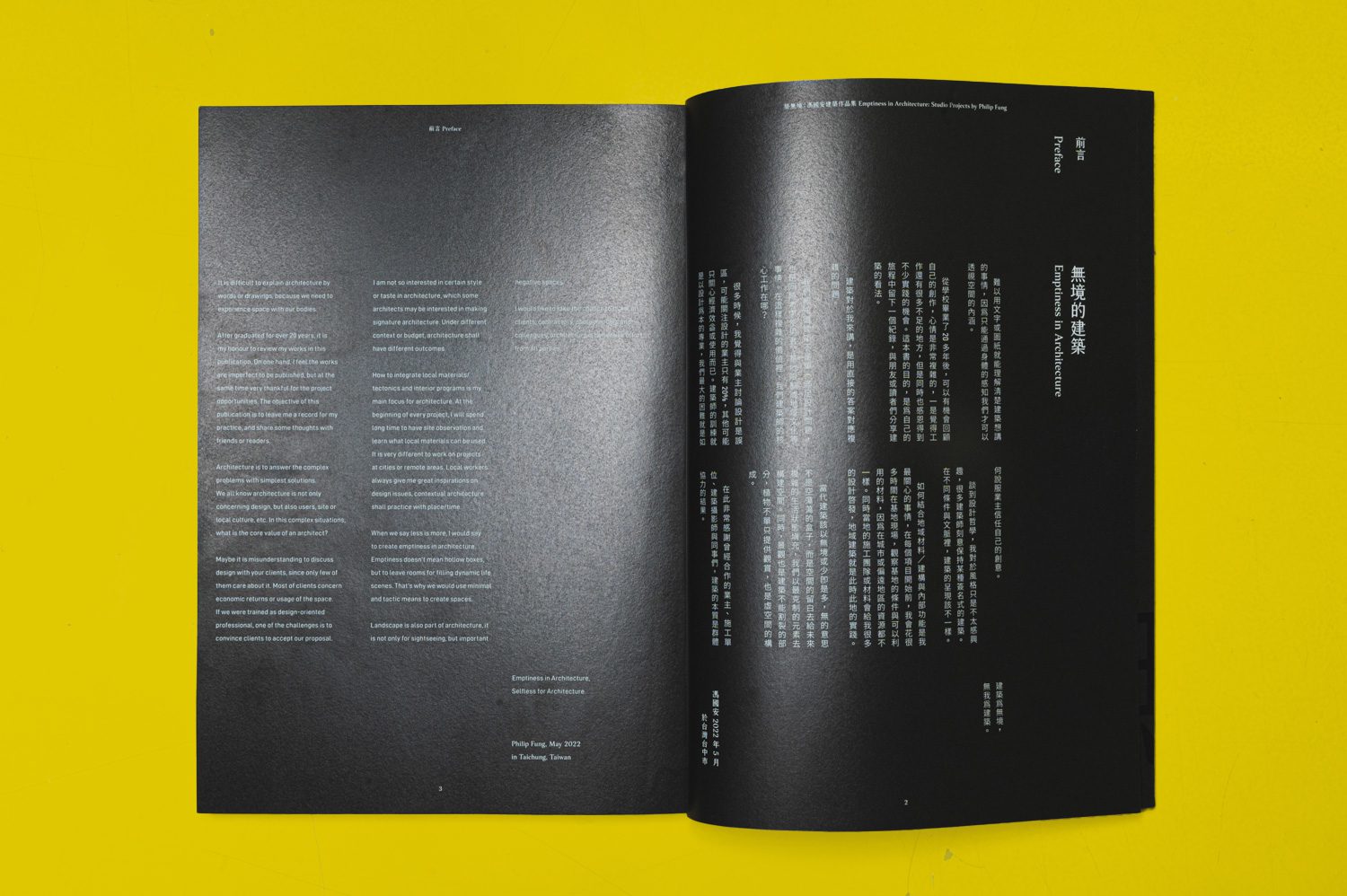

“When we say less is more, I would say it is to create emptiness in architecture. Emptiness doesn’t mean hollow boxes, but rather to leave room for dynamic life scenes to unfold. That’s why we would use minimal and tactical means to create spaces.”

This passage appears in the foreword to Emptiness in Architecture, a bilingual volume (Chinese and English) published by Garden City Publishers (田園城市生活風格書店) in Taiwan. The book brings together over two decades of work by Philip Fung (馮國安), the Hong Kong-born architect who founded Elsedesign in Taiwan. Fung’s formative years included time at Herzog & de Meuron, and he now serves as an assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at Tunghai University. Across six chapters: Duality, Formless, Complexity, Livelihood, Ideology, and a concluding Reflection, the book traces Fung’s approach to architecture and furniture design.

In the opening chapter, Duality, Fung examines the notion of coexistence through two selected projects. Both are exhibition designs that fold together opposing ideas. In In Out Table (2013), the carefully thought-out placement of the exhibited pieces simultaneously serves as the bridge between inside and outside, forging connections between people and art. Meanwhile, the Haozai Exhibition at Beijing Design Week (2015) brings Eastern and Western furniture into dialogue, using a single wall to divide, and at the same time, unite two distinct spatial realms.

Beyond the relationship between space and art, Fung’s work also explores the dialogue between the surrounding environment and the identity of each piece. The second chapter, Formless, brings together both architectural and furniture projects, and stands as the book’s most expansive section. The term ‘Formless,’ taken literally, means ‘without form,’ pointing to an approach that resists predetermined shapes in favor of designs shaped by context and environment. Each project responds to its specific setting rather than imposing a fixed idea of form. In this chapter, Fung presents seven works that embody this ethos. Among them is So-fa-so-good (2016), a piece inspired by the topography of China. Here, an ordinary rectangular sofa transforms into a continuous whole, with its backrest flowing seamlessly into the seat. The design allows multiple units to be arranged in endless configurations, adapting to the user’s needs and the space they inhabit.

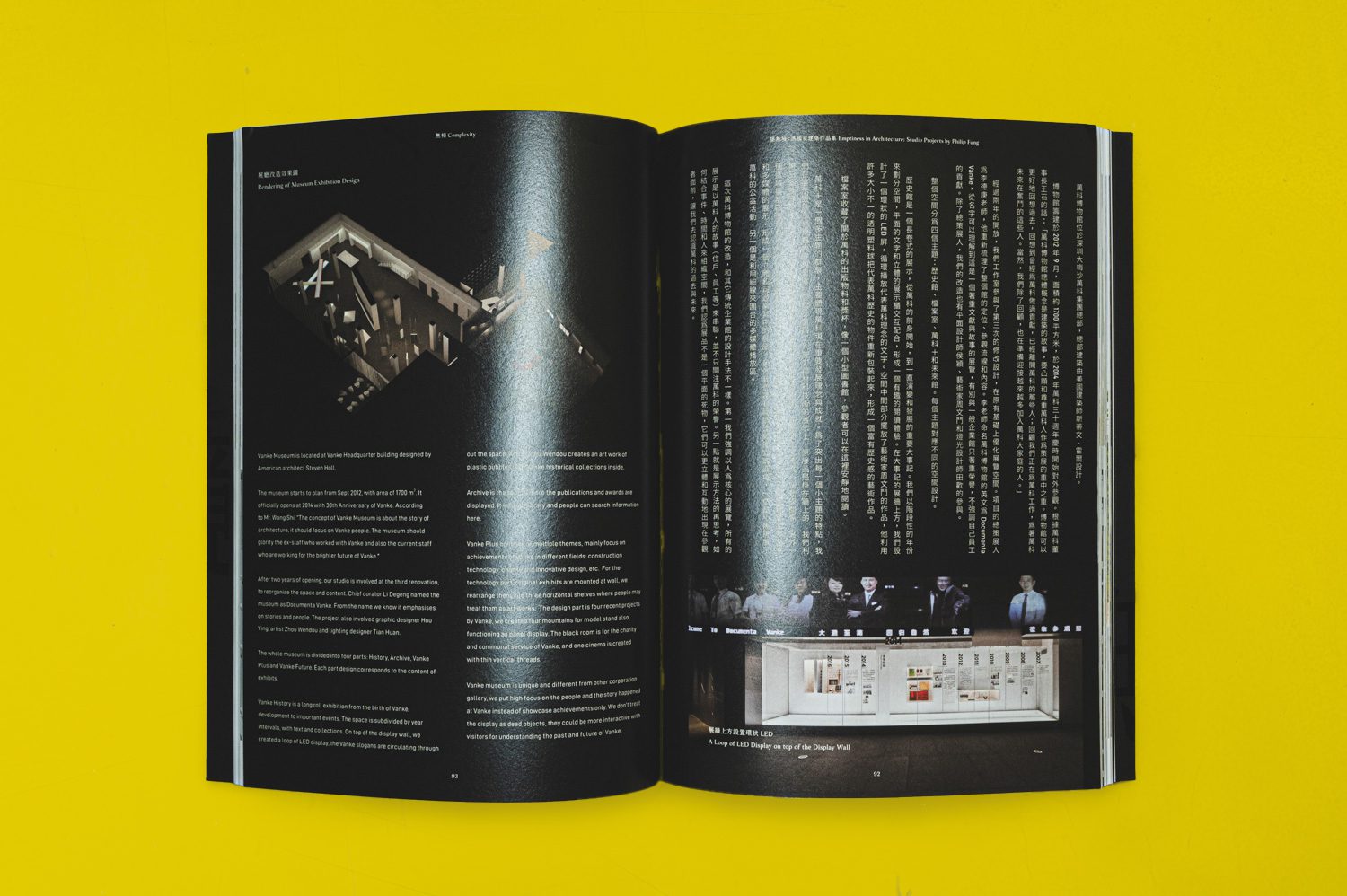

The third chapter, Complexity, shifts focus to buildings conceived around the intricate dynamics of coexistence among people, cities, and architecture. Rather than simply arranging functions or forms, these projects navigate the layered overlap of physical space, perception, and lived experience. One such example is Forest, a workshop held in Taipei, a city that stands as a vibrant cultural crossroads. Taipei’s urban fabric embraces stark contrasts, from local markets to sleek metropolitan enclaves. The question Fung poses through Forest is how design can generate meaningful experiences from these extremes.

Forest was installed in the waiting hall of Yuan Ze University in Taiwan, a space that sees a constant flow of people passing through. To give physical form to the city’s contrasts, Philip Fung and his students suspended one thousand wooden rods from the ceiling, each extending almost to the floor. For those standing within the space, the rods reach down nearly to knee height, creating the impression of a floating forest. As people and breezes move through, the rods sway gently, bringing the installation to life. In doing so, this once-transitional lobby; a place to wait for the lift or pass from one area to another, is transformed into a site of quiet interaction between people and place.

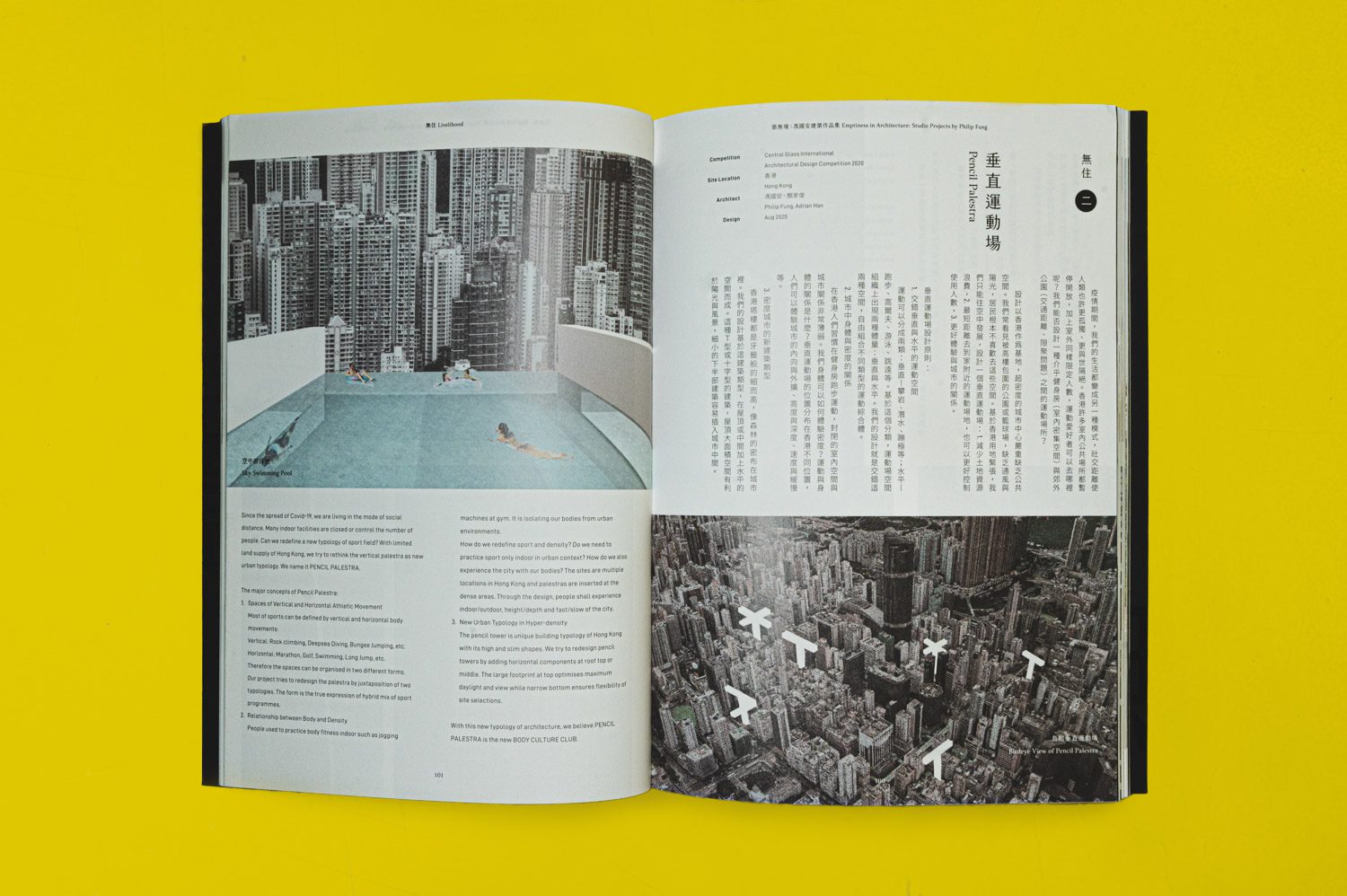

The following chapter, Livelihood, delves into the fraught relationship between ‘housing’ and ‘urban density,’ taking its cue from Hong Kong’s famously compact context. Here, people endure crushing housing costs and, for the most part, can afford only cramped apartments. Although Hong Kong is surrounded by mountains and abundant green space, it remains difficult for many to truly enjoy these natural assets. Every bit of land feels squeezed to serve as living space, yet livability stays just out of reach. This tension has inspired Fung to explore design interventions that address these urban challenges. The chapter presents a range of thought-provoking projects, from vertical habitats for animals to new models of vertical exercise spaces, and even proposals that merge affordable housing units with protruding billboard structures.

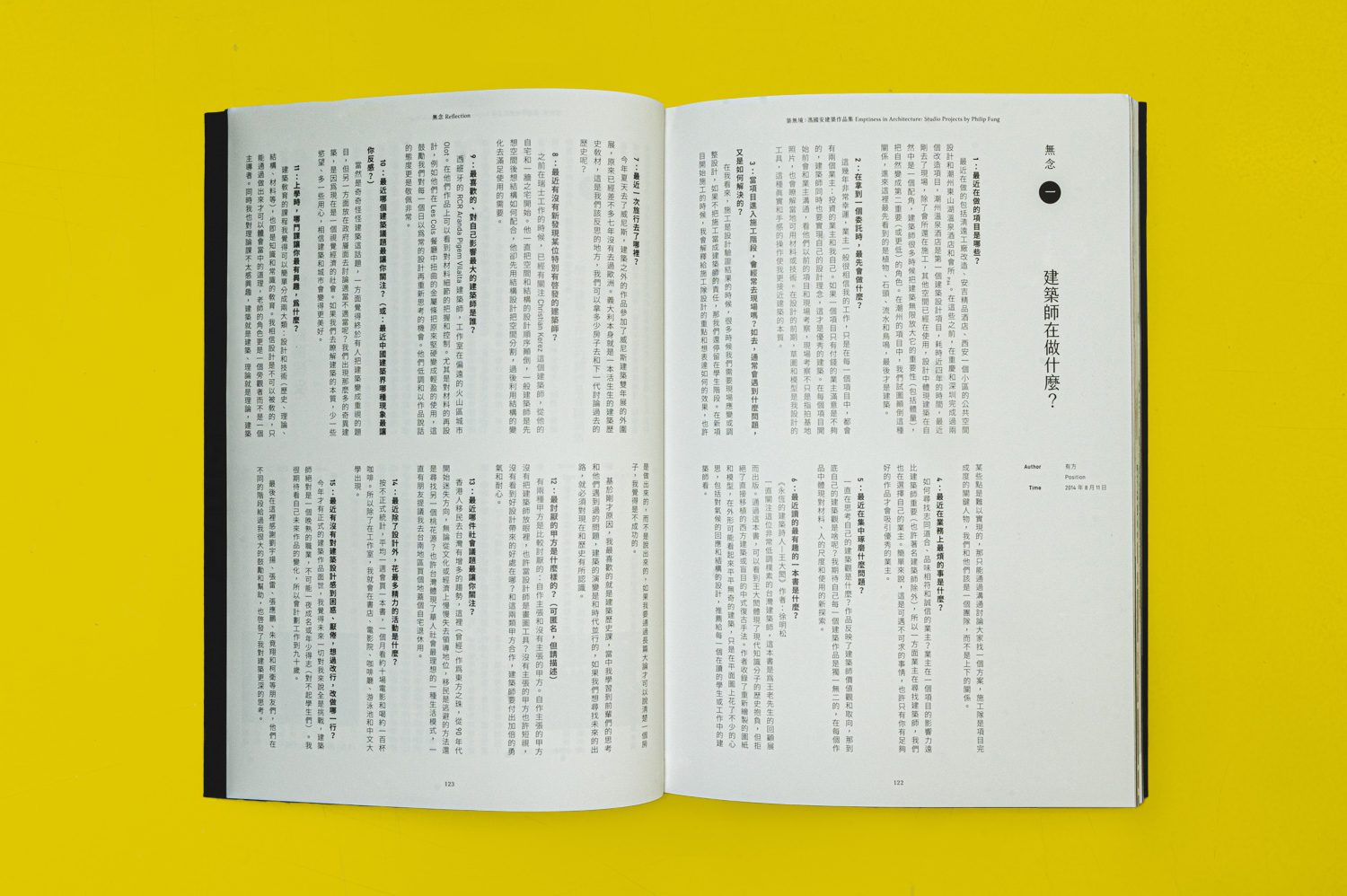

In the fifth and penultimate chapter, Ideology, Philip Fung reflects on his experiences as both architect and educator, sharing the experimental projects and fresh ideas that have emerged from his students’ hands. These glimpses reveal an imagination and creative spirit unbound by conventional constraints.

One particularly interesting detail is that, while the entire book is presented bilingually throughout its chapters, the final section, Reflection, appears solely in Chinese, without a single word of English. Here, Fung shifts to a more personal register, weaving together thoughts on culture, daily life, interviews, and design in an informal tone. One might infer that telling this closing chapter in his native language is his way of offering Chinese-speaking readers the most intimate view of his thinking; a space where nothing risks being ‘lost in translation.’

The six sections that make up this book are each framed by brief definitions that Philip Fung includes at the opening of every chapter, somewhat succinct descriptions that help outline the thinking behind each thematic focus. Though Emptiness in Architecture comes with the unique challenge of blending two reading systems: vertical Chinese text and horizontal English, along with a right-to-left reading order, its clean, orderly layout of images and text makes the experience remarkably approachable.

The book illuminates Fung’s perspectives on design, whether architecture or other forms of spatial practice, by presenting ideas that might otherwise feel abstract and complex in a way that is clear and accessible. Each section is thoughtfully structured so that proportion, pacing, and content guide the reader through straightforward examples that ground his philosophy in real projects. Ultimately, the book does not seek to offer a complete or final conclusion about design. As Fung writes in the foreword, Emptiness in Architecture was never intended to present the ‘perfection’ of design, but rather to capture a moment in his practice and share fragments of his thinking with friends and readers alike.

From its title, Emptiness in Architecture, the answer to the question of what ‘emptiness’ means in the work of Philip Fung and his studio Elsedesign may well be that ‘emptiness’ is not as a literal void, but a way of shaping space, both positive and negative, and leaving room in the mind for other things to flow in and fill that space, endlessly and without finality.