DESIGNED BY COLLAGE DESIGN STUDIO, OFFICE NO.81 TRANSFORMS AN OLD BUILDING IN THE SUKHUMVIT AREA INTO A NEW RESIDENTIAL AND OFFICE SPACE

TEXT: XAROJ PHRAWONG

PHOTO: PANORAMIC STUDIO EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

If architecture is understood to possess a corporeal form like the human body, then the spirit that animates it is its program. The body, meaning the physical structure and architectural elements, is inevitably shaped and worn by time, requiring ongoing care and maintenance throughout its lifespan. The spirit, on the other hand, evolves with the times, shifting in response to changing behaviors, needs, and the social conditions that define each era. When the body can no longer serve the spirit it once housed, the process of transformation, commonly known as renovation, begins.

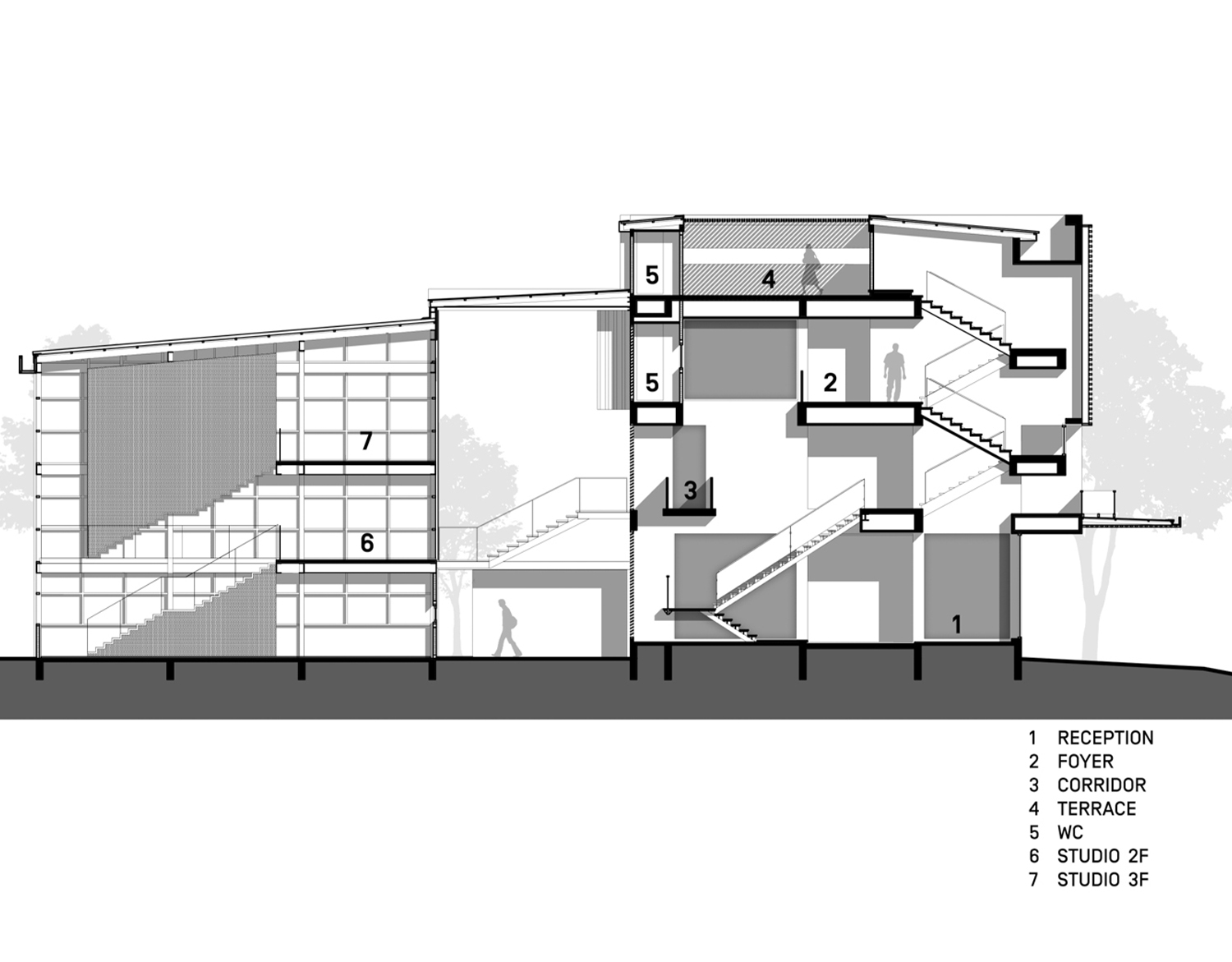

Office No.81 was originally a dual-unit residence functioning as a live-work space, with two adjoining buildings separated by a shared central wall and mirror-image staircases at the core of each unit. A storage warehouse stood at the rear. When the time came to renovate the site, the architects were tasked with reimagining it as a space that could accommodate both residential life and a flexible new mode of working. The brief called for shared work areas in the style of a co-working space, an upgraded warehouse repurposed for artistic production, and an area dedicated to exhibitions.

Adaptive reuse refers to the practice of assigning new value to existing structures. It involves reworking the body of architecture to embrace a new spirit, allowing both to coexist in a way that brings about the greatest benefit with the lightest possible touch. Despite its subtlety, this approach can lead to profound transformation. In economic terms, adaptive reuse reduces the need for new resources by maximizing the potential of what already exists, a result made possible through intentional design. We can see this principle at work in case studies around the world, where old buildings are preserved with only minimal alterations. Through thoughtful design, which in itself is a form of problem-solving, constraints become a framework that guides the creative process. The result is often surprisingly inventive. When a new conceptual layer is applied, historical architecture is reimagined with renewed beauty, allowing it to remain relevant in a rapidly changing world. This idea extends beyond the scale of a single building. When applied across the urban fabric, adaptive reuse has the potential to drive transformative change on a much larger scale.

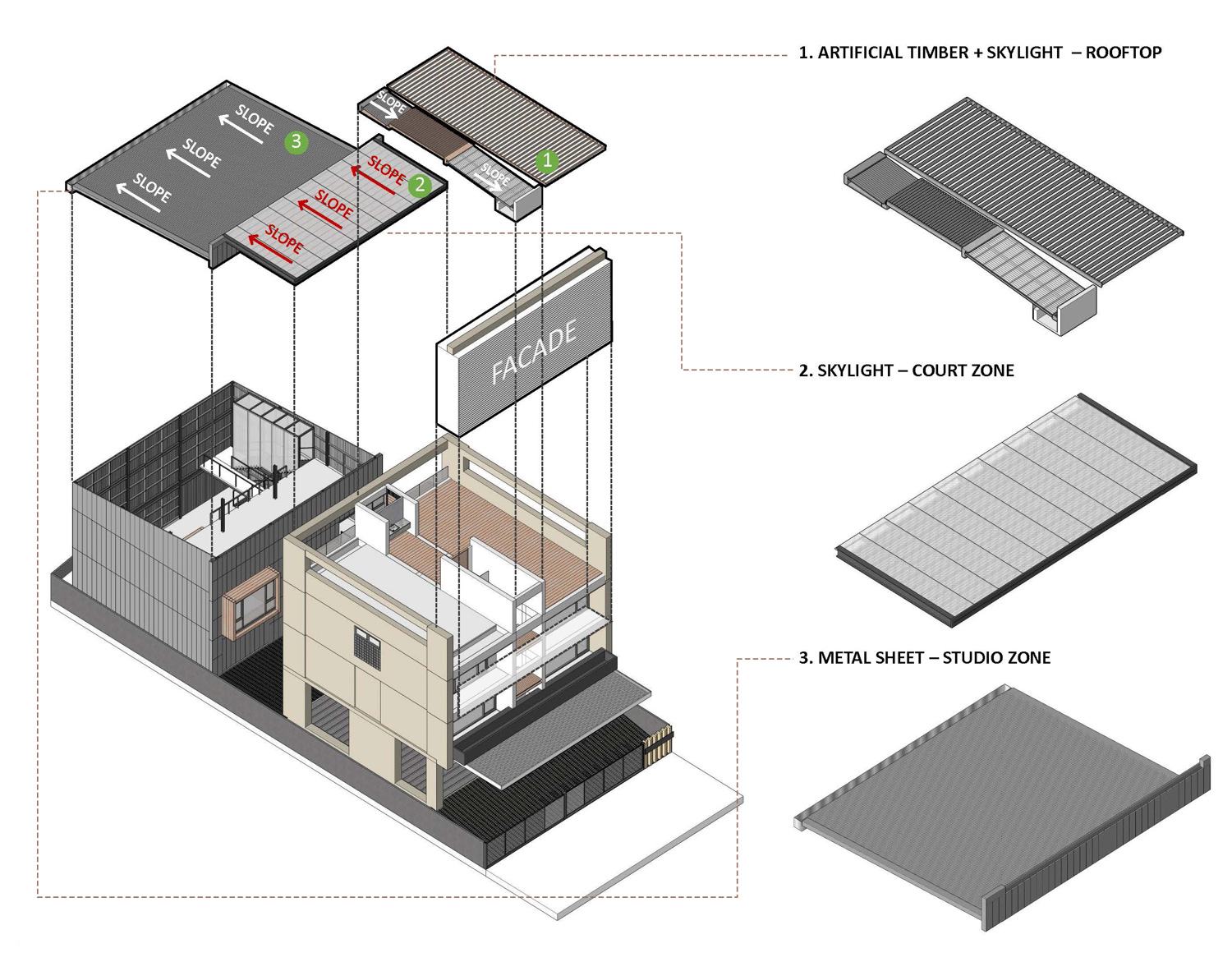

In response to the client’s brief, the architects at Collage Design Studio reorganized the spatial layout to enhance flexibility. The front building underwent a significant reconfiguration. The staircase on the first floor was relocated toward the rear, and part of the existing floor slab was removed to create a more open and fluid stairwell, allowing visual continuity all the way to the third floor. Where the interior had once felt enclosed, the use of light tones helped brighten the space and expand its perceived volume. The rear warehouse, previously used for storage, was transformed into an art studio, with provisions made for a gallery space. Originally a two-story structure, it was reimagined into a three-level space through the addition of a mezzanine. The resulting architecture embraces fluidity, avoiding a full build-out to preserve openness and lightness. A bridge on the second floor connects the office building with the newly adapted studio, creating a circulation path that unites the two structures. The void between them was converted into a multipurpose courtyard, which also functions as a shared ground-level space, linking the first floors of both buildings. This configuration reduces the sense of density and enclosure often found in the tight urban fabric of Bangkok’s Sukhumvit Soi 81.

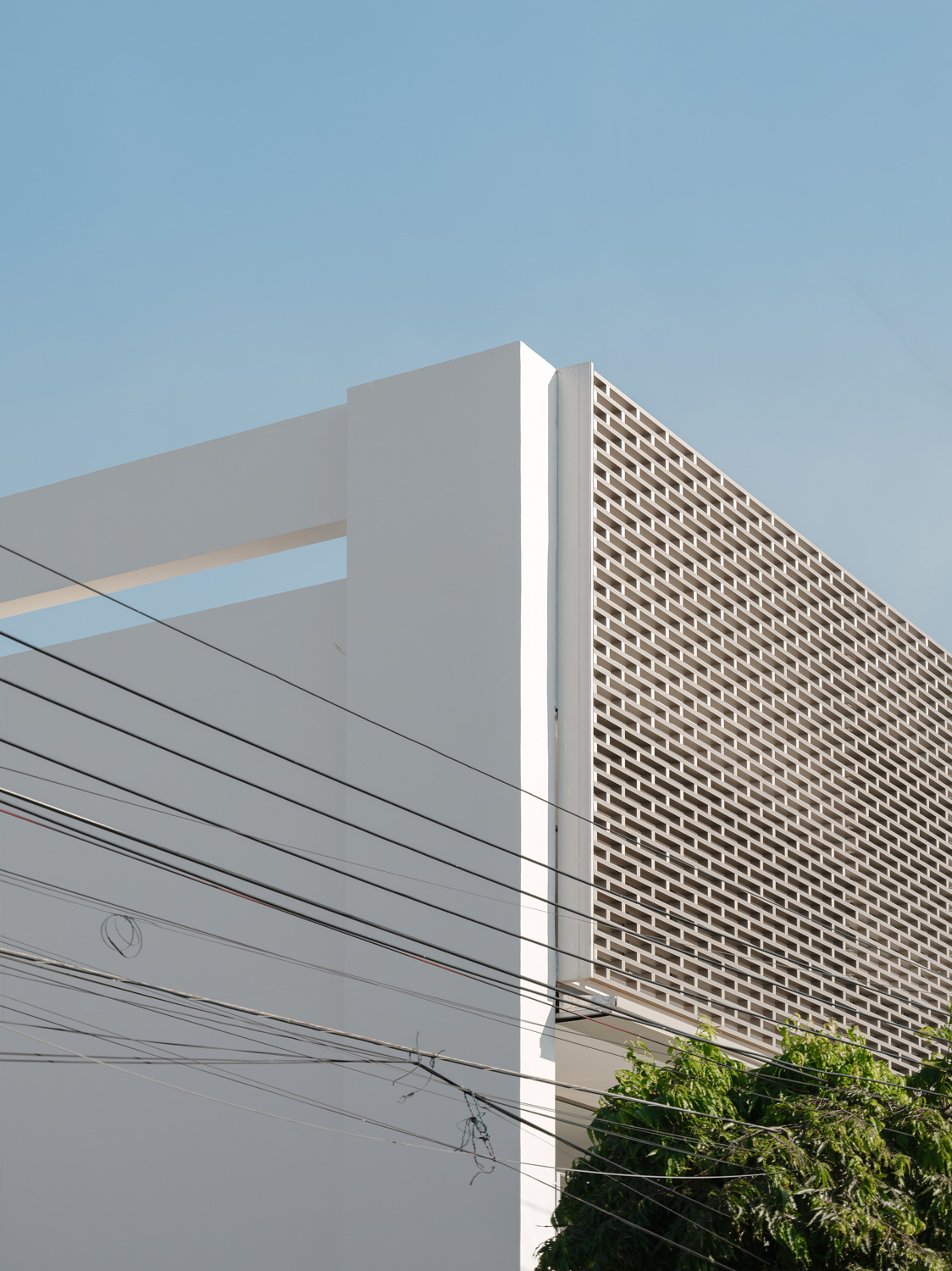

Another aspect of the project involved strategic consideration of materials. The architects selected aluminum box sections measuring 50×100 millimeters, valued for their durability, light weight, ease of maintenance, and straightforward installation. The material’s compatibility with the existing structure and its long-term adaptability also contributed to its selection. Beyond their conventional use as window and door framing, the architects reimagined these aluminum sections as integral architectural components. The front façade faces southwest, the direction that receives the most sunlight throughout the year. On the third floor, which houses the private living quarters, privacy and thermal comfort were key concerns. The design intervention began with a need to reduce solar heat gain while maintaining a sense of enclosure.

The architects repurposed the aluminum box sections as a horizontal sunshade system spanning the full width of the façade. To prevent structural deflection and sagging, which are common issues with long horizontal spans, the architects rotated the aluminum members vertically and arranged them in an overlapping pattern reminiscent of brickwork. This configuration provided structural stability while generating a distinctive visual rhythm.

From the exterior, the screen subtly obscures interior activity and enhances privacy. Inside, the shifting interplay of light and shadow casts brick-like patterns on the walls and floors, creating a dynamic spatial quality that evolves throughout the year. Because the screen is made of aluminum, a material that resists heat retention and is lightweight, it fulfills multiple performance goals. The solution achieves a balance between material efficiency, architectural expression, and functional performance by providing solar shading, diffusing natural light, reducing reliance on artificial illumination, and supporting passive ventilation.

The act of adapting one element for use in a different context requires a process rooted in design thinking. It involves searching for answers beyond the familiar and often leads to entirely new solutions, ones that may simply reside in places we tend to overlook.