A CONVERSATION WITH INW COLLECTIVE ON HOW THEIR CURIOSITY ABOUT INFORMAL URBAN LIFE LED TO AN ALTERNATIVE WAY OF INTERPRETING THE CITY

TEXT: PHARIN OPASSEREPADUNG

PHOTO: KITA THAPANAPHANNITIKUL

(For Thai, press here)

Have you ever wondered about the small, seemingly insignificant objects scattered across the city? Where did they come from? Why are they here, in this exact spot? In the rush of everyday life, such questions often go unasked, brushed aside by the momentum of routine. For inw collective, a group of five individuals from different professions and backgrounds, including architects, graphic designers, and character designers, curiosity is precisely what brought them together. That shared sense of wonder became the driving force behind a series of urban explorations, workshops, and most recently, their debut exhibition, Zine Exhibition: IT’S NICE TO WONDER, which concluded on July 13, 2025.

Held at Neighbourmart on the ground floor of TCDC, the exhibition invited viewers into five distinct worlds of urban curiosity, each presented in a handmade zine. The stories span everything from bright blue pipes that somehow solve every municipal problem, to a data-driven study of Thai barbecue joints, an exploration of wrought iron as an urban emblem, a catalog of 101 objects designed to improve city life, and even a secret hero dossier rooted in Bangkok lore. Together, these zines transform the overlooked details of the city into subjects of inquiry and delight.

What makes these zines particularly compelling is how each one reflects the playful curiosity and creative energy of its author. While the exhibition has ended, the spirit of inquiry it sparked feels far from over. It leaves us wanting to know more: about the process behind the work, the unexpected discoveries made during their city walks, and how these individual fascinations eventually evolved into zines and culminated in this exhibition.

To find out, art4d sat down with the five members of inw collective: Chatchavan Suwansawat, Chakorn Kajornchaikul, Romrawin Pipantnudda, Supanut Lertrakkul, and Suwicha Pitakkanchanakul. The conversation delved into the origins of their collaboration, the questions that drew them together, the creative impulses behind each zine, and their distinct ways of seeing and interpreting the city.

(from left to right): Chatchavan Suwansawat, Supanut Lertrakkul, Chakorn Kajornch, and Romrawin Pipantnudda

art4d: Tell us how inw collective came together. What’s the backstory?

Chatchavan Suwansawat: It started with my interest in organizing city walks. I’ve always been fascinated by the informal aspects of urban life, what you might call informal living. Things like street food vendors and those spontaneous, organic phenomena that emerge naturally in the city. After hosting several walks, I began meeting younger participants who shared similar interests. It felt natural to think: what if we worked on a project together? We could expand this space of understanding and bring something fresh to the city. It began as a kind of pilot project to see what we could do collaboratively.

Supanut Lertrakkul: Once we decided to form a group, we started talking about our interests and what kind of work we wanted to create. The name came about in a very lighthearted way. At first, someone suggested ‘Squirrel of the City,’ completely at random. Then came ‘Win,’ inspired by Bangkok’s motorbike taxis, which are referred to by locals as ‘win motorbikes.’ That’s when Neoy (Suwicha) said, “What if we flip WIN around? It becomes INW, and when you read it in Thai, it looks like the word เทพ (thep), which means ‘epic’ or ‘cool’.” Everyone loved it immediately, so it stuck.

art4d: So the name doesn’t actually tie back to Bangkok, even though เทพ (thep) might sound like it does, given that Bangkok’s Thai name is Krung Thep.

Romrawin Pipantnudda: Right. It started with walking around Bangkok, but we’ve tried to strip away the ‘Bangkok’ part. We used the city as our ground for exploration, but really, this sense of wonder could take place anywhere.

art4d: Once you had the name inw, how did that lead into the exhibition IT’S NICE TO WONDER?

Chatchavan: After we formed the group, we started working seriously on the exhibition. We thought, what if inw could also be a phrase that sums up what we do? That’s how IT’S NICE TO WONDER came about. Whenever we explore the city, we’re always struck by these tiny, overlooked details. We’d ask questions, dig deeper, and find ourselves spiraling into research. That’s where the name came from. Then we each looked at what fascinated us individually and what we wanted to do. Each of us already had very clear areas of interest, so it came together quite naturally.

art4d: What were each of your interests that eventually shaped the zines featured in this exhibition?

Chatchavan: I created two zines. One of them came from something I’d been fascinated by for a long time: those blue PVC water pipes you see everywhere and how they seem to be used for everything. As an architect, I’m naturally drawn to materials, and this one stood out to me because it’s so versatile and so ubiquitous. For the exhibition, I turned this small but telling observation into a zine called ‘Blue Pipes – Raw Material for Thai Everyday.’ Over the years, I’ve been photographing them, and I’ve realized they reflect more than just their function. They speak to social realities in subtle ways. You see them in protest signs, where the pipes are used as makeshift poles, or in the improvised bathrooms on construction sites. They’re always present, often in situations that demand quick fixes or immediate solutions, and in that sense, they reflect a certain kind of survival instinct embedded in our society.

Chakorn Kajornchaikul: My zine is about Bangkok’s own superheroes. It’s called ‘Secret File – BKK.’ I’ve always loved superheroes, so I started imagining what it would be like if Bangkok had its own. When you look closely, the city is already full of objects with their own stories and character, but no one really treats them that way. During our city walks, I kept noticing things like utility poles, blue pipes, or those barriers used to block parking spaces. This led to a challenge I created called #KrungFeb in February, where I drew 28 Bangkok-inspired characters, one for each day of the month. For this zine, I framed it as if there were a secret organization cataloging these ‘powers’ around the city, turning those 28 characters into a classified dossier. It really opened my eyes to how many overlooked elements of Bangkok could be reimagined in fun, creative ways.

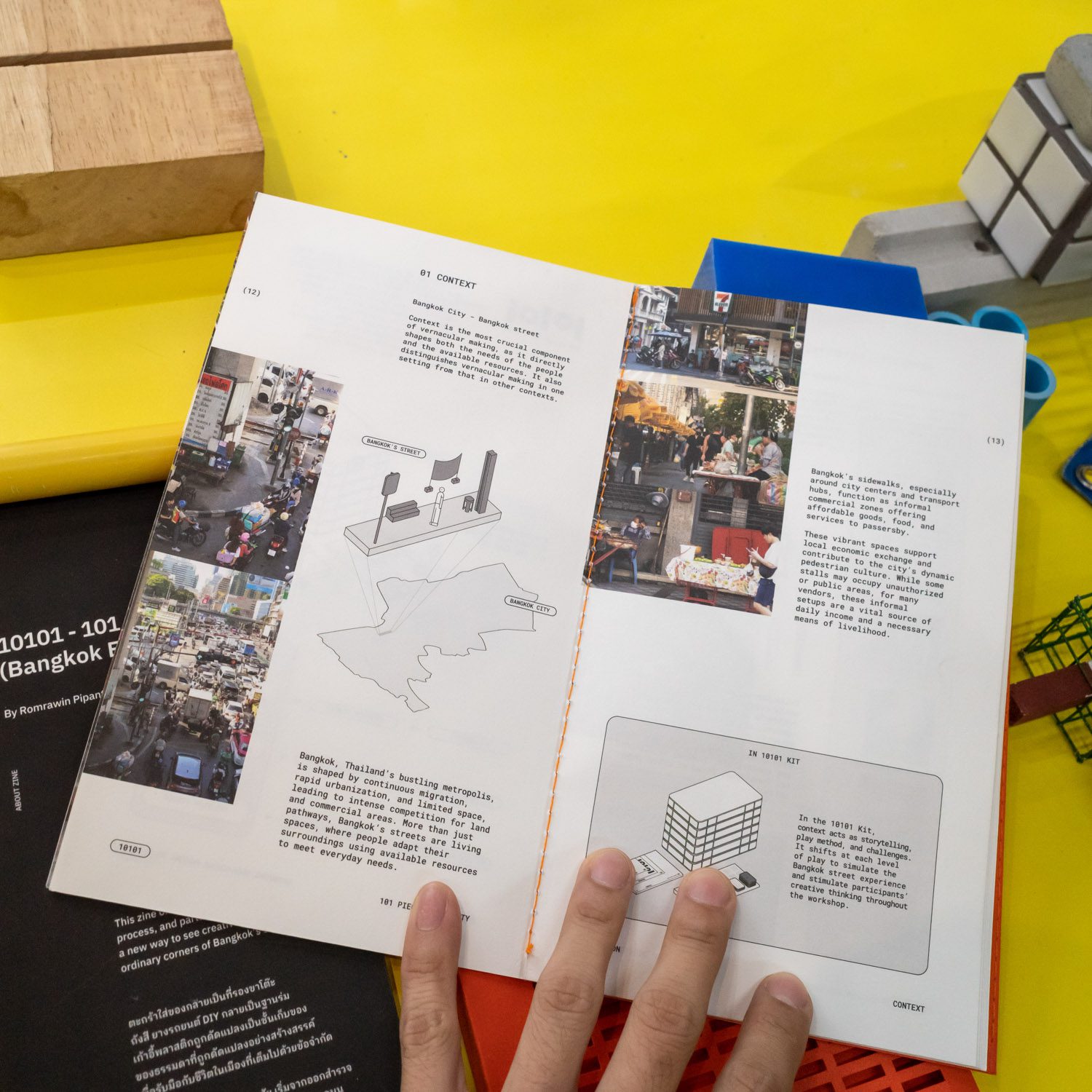

Romrawin: I’ve always been interested in ‘objects,’ especially those improvised, homespun solutions people come up with. When I got serious about exploring the city, especially during my thesis, I started actively seeking out these kinds of things. That eventually became my project ‘10101 – 101 Pieces for 1 City (Bangkok Edition).’ It’s essentially a set of tools designed to spark creativity, like LEGO, but built entirely out of 101 components from the city itself. The idea is for people to use these pieces to come up with their own ways of solving problems. Along the way, they also learn more about the city through these objects; things they may never have paid attention to before. For example, steel pipes from electric poles or parts of pedestrian bridges. These aren’t things most people consider beautiful, and they’re often dismissed as ugly or mundane. But they’re all products of design. Someone faced a specific problem and came up with a solution using what they had around them.

Supanut: My zine is called ‘Bangkok Moo Ka Ta’ (Bangkok Barbecue Joints). It’s actually more of a side quest for me. My main focus has been running a photo account called ‘Typography Photo,’ where I document old signage. It started simply because I love fonts and typography. On days when I have nothing to do, I find myself searching for fonts on Facebook or Instagram without even thinking about it. It just makes me happy. Over time, I built up this huge personal archive of photos. But when it came to making a zine, it wasn’t practical to include everything I’d ever shot, so I narrowed it down by randomly picking 100 moo ka ta (Thai barbecue) restaurant signs and analyzing them. That’s when I noticed interesting data patterns. For instance, out of 88 sticker signs I looked at, every single one spelled ‘กระทะ’ (pan) incorrectly. They all left out the letter ‘ร’ and used the incorrect spelling, ‘กะทะ.’ Or how certain phrases repeat across signs: like ‘Free Pepsi.’ No one ever writes ‘free delicious soft drink.’ It’s always ‘Free Pepsi,’ and it’s always paired with the Pepsi logo.

art4d: Unfortunately, Neoy (Suwicha) couldn’t join us today due to other commitments, so Chat, could you tell us about her work?

Chatchavan: Neoy is fascinated by wrought iron window and door grilles. We tend to think of them purely as anti-theft devices, something functional to protect a home. But as she explored the city, she began to see them differently. They carry cultural meaning, stories, and symbolism. For example, if you walk past the home of a prominent family named Suea (which means ‘tiger’), their wrought iron grille might be shaped like a tiger. Her zine, ‘Goood Grills in Bangkok,’ came from this kind of observation. She had always heard the term ‘khaek fai yam’ (literally ‘the Indian guard’) but never really understood it, until she came across a wrought iron grille shaped like an Indian man standing guard. That discovery became the spark for her to document these grilles extensively across the country, though this zine focuses on 50 examples from Bangkok, each with its location so people can track them down. What’s interesting is that some of these grilles eventually disappear, so even if you go looking for them later, they may already be gone.

art4d: So all of these zines essentially came out of walking through the city. What else do you gain from walking? Why do you guys enjoy it so much?

Supanut: Walking is a form of exploration. It offers a kind of value you simply can’t get online. Even the difference between someone who takes the train and someone who walks is huge. They notice completely different things. One of the best parts of walking is that it slows you down. When you’re in a car or on a train, you speed past things without a chance to notice them. But walking lets you see more. You can slip into alleys cars can’t reach or wander into places no one would ever think to take you, simply because you’re curious enough to go.

Romrawin: For me, it really changed the way I live. Before I started working on my thesis, I was always in a rush. Living far out, I just wanted to get into the city quickly. But once I began this project, I started walking more, and it helped me connect with the places I was in. I discovered little alleys, local restaurants. Things I’d never noticed before. It was only when I began spending more time moving through these areas on foot that I truly started to feel like I was part of the neighborhood, or even the city. Now, whenever I have time, I prefer to walk.

Chatchavan: Walking is one of the most basic things humans do. Simply stepping out of your house and walking means you’ve already begun. And you might end up gaining more than you expect. Whenever life feels monotonous or stuck in routine, walking helps me see something new. I get that walking in our cities isn’t always easy, but it’s still possible to a certain degree. Personally, I think it’s worth it just to start exploring the areas close to where you live.

art4d: From all your time spent walking, what’s one thing in the city you’d want to see remain? Something you’d still like to find five or ten years from now.

Supanut: Street-side restaurants, definitely. When you walk through smaller neighborhoods, these places often become informal hubs. You can ask for directions or chat with the owner about the area. ‘How do things work around here? What time does the shop open?’ They’re points of connection, both between us and the community, and within the community itself.

Chakorn: I agree. These places help feed the people who live and work nearby. Some might see them as unsightly or unhygienic, but they’re vital for the lower-income workers who keep the city running. They’re part of what makes the city liveable.

art4d: And what about the two of you, how do you see it?

Chatchavan: I don’t think it’s possible for things not to disappear. They inevitably do, over time. We can’t stop or force them to remain in place forever. What matters is how we remember them, and how we learn to capture and share what we’ve encountered during that moment in time as best as we can.

Romrawin: Eventually, yes, they will fade with time. As someone who explores the city, it’s bittersweet to see things go. The existence of these objects, in a way, reflects the problems people in the city have tried to solve for themselves. So when something disappears, maybe it also means that the problem it represented has been resolved. Perhaps its absence is a sign of progress too.

art4d: Now that Zine Exhibition: IT’S NICE TO WONDER has wrapped up, what’s next for inw collective?

Romrawin: At its core, the word collective simply means a group of people coming together. It doesn’t prescribe who those people should be or how it has to work. What’s important is amplifying the voices of those speaking about the same things. For us, it all started with curiosity and the joy of wanting to think and try things out. So whatever comes next will likely begin in the same way: if it’s fun, thought-provoking, and worth doing, then we’ll keep going and make it happen.