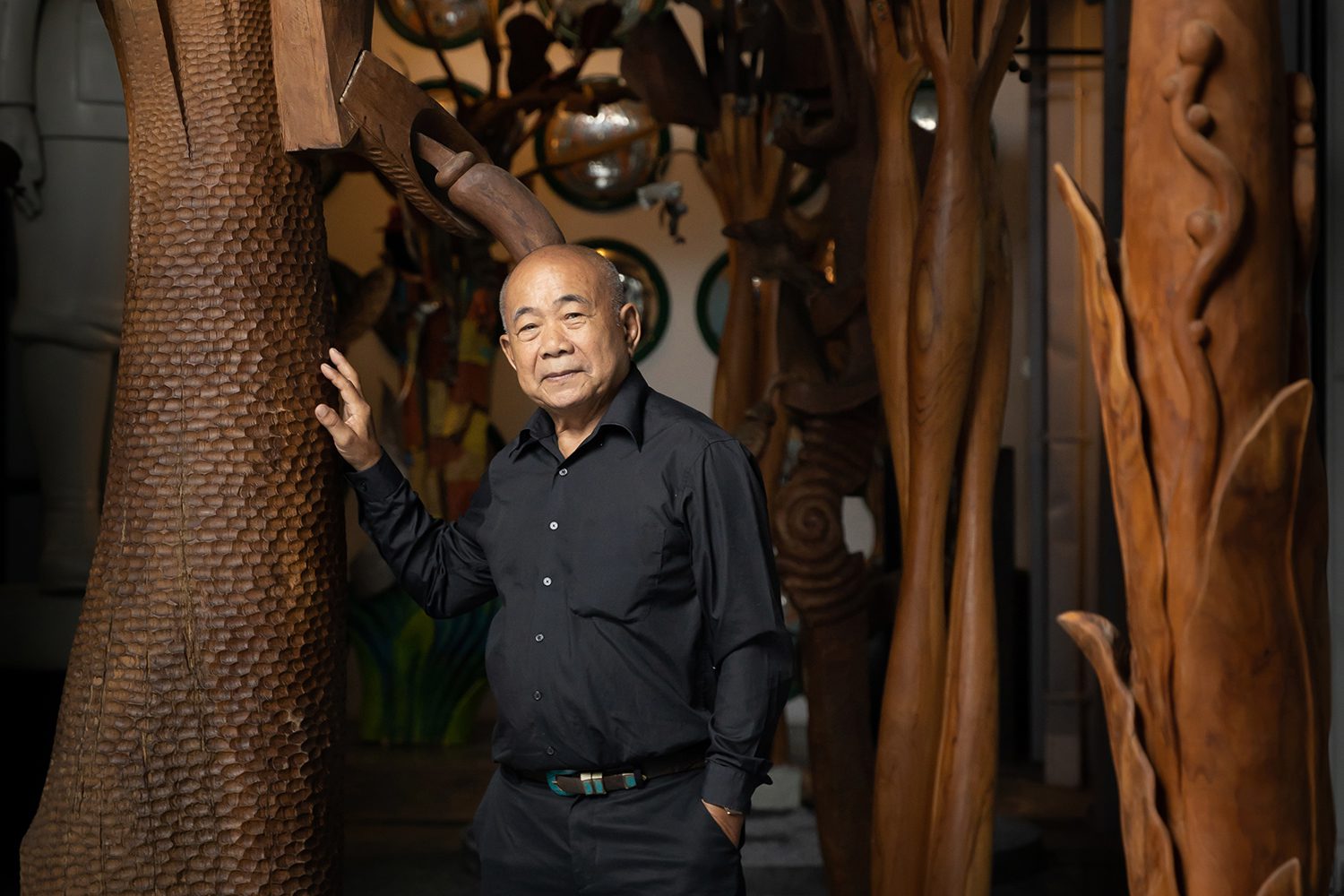

IN CONVERSATION WITH PEERAPONG DOUNGKAEW, CREATOR OF THE SCULPTURE ‘BIODIVERSITY,’ WHO CHANNELED THE FRAGILITY AND INTERCONNECTEDNESS OF LIFE WITHIN ECOSYSTEMS THROUGH HIS CARVED WOODEN SCULPTURES

TEXT: PRATARN TEERATADA

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

An accomplished art educator and senior sculptor, Peerapong Doungkaew seamlessly weaves elements of ‘rootedness’ from multiple dimensions into his contemporary artistic practice. His work, often realized through semi-abstract forms and reclaimed natural materials, speaks to his deep concern for the environment and the pervasive impact of human activity. Recently, his focus has shifted towards exploring the symbiotic relationships within ecosystems, alongside a hopeful vision for restoring the vital connection between humanity and nature. Through his art, he urges a thoughtful reckoning with humanity’s role in the ecosystem; an invitation to confront the urgent and profound questions surrounding our responsibility in a world where nature grows increasingly fragile, and the consequences of human impact become ever more undeniable.

In this conversation, art4d delves into Peerapong’s early journey as a sculptor, the philosophy behind his works inspired by local cultural roots, his approach to creating art through scientific research, and his enduring role as an educator, imparting his knowledge to generations of artists over several decades.

art4d: Could you take us back to the moment when you first decided to become an artist? What skills did you begin to cultivate, and why did you choose sculpture as your path in the early days?

Peerapong Doungkaew: I grew up as the child of civil servants. My father was a teacher who graduated from Poh-Chang Academy of Arts, and after finishing his studies, he continued to work there, handling accounts, managing budgets, and teaching woodworking. Back then, they referred to the subject as ‘carpenter hardware.’ My mother was a primary school teacher, and because my father later took a position in Ubon Ratchathani province, I naturally became an Ubon native.

As a child, I was always intrigued by the tools my father had. He would have chests filled with chisels, saws, axes, and more. And I would play with these tools without truly understanding their purpose, carving this and shaping that. I would transform pieces of wood into slingshot forks, then use them to shoot, or carve boats, buffaloes, worms, beetles and other simple shapes. I was just making toys. In those days, store-bought toys were a rarity, so we had to create our own using these tools. On occasion, my father would catch me using the sharp tools, and he would scold me, warning that these were professional tools meant for craftsmen and I should handle them carefully to avoid dulling them. But this is where my fascination with these tools began, even though I didn’t realize it at the time.

Throughout elementary and high school, I developed a growing interest in art, perhaps a passion I inherited from my father. I loved drawing and sketching. After finishing junior high, I secretly decided to pursue this interest further, despite my father’s wishes for me to become a teacher. I ended up passing the entrance exam for Poh-Chang Academy of Arts. There, I was introduced to the basics of drawing, which provided me with a strong foundation, including anatomy. From there, I went on to study at Silpakorn University, where I chose to major in sculpture. Part of the reason was the familiarity I had with sculpture from my childhood, but another factor was the fact that the sculpture program had fewer students. Painting was more popular, likely because it was lighter and easier, while sculpture required a great deal of physical effort and energy to bring an idea into three-dimensional form.

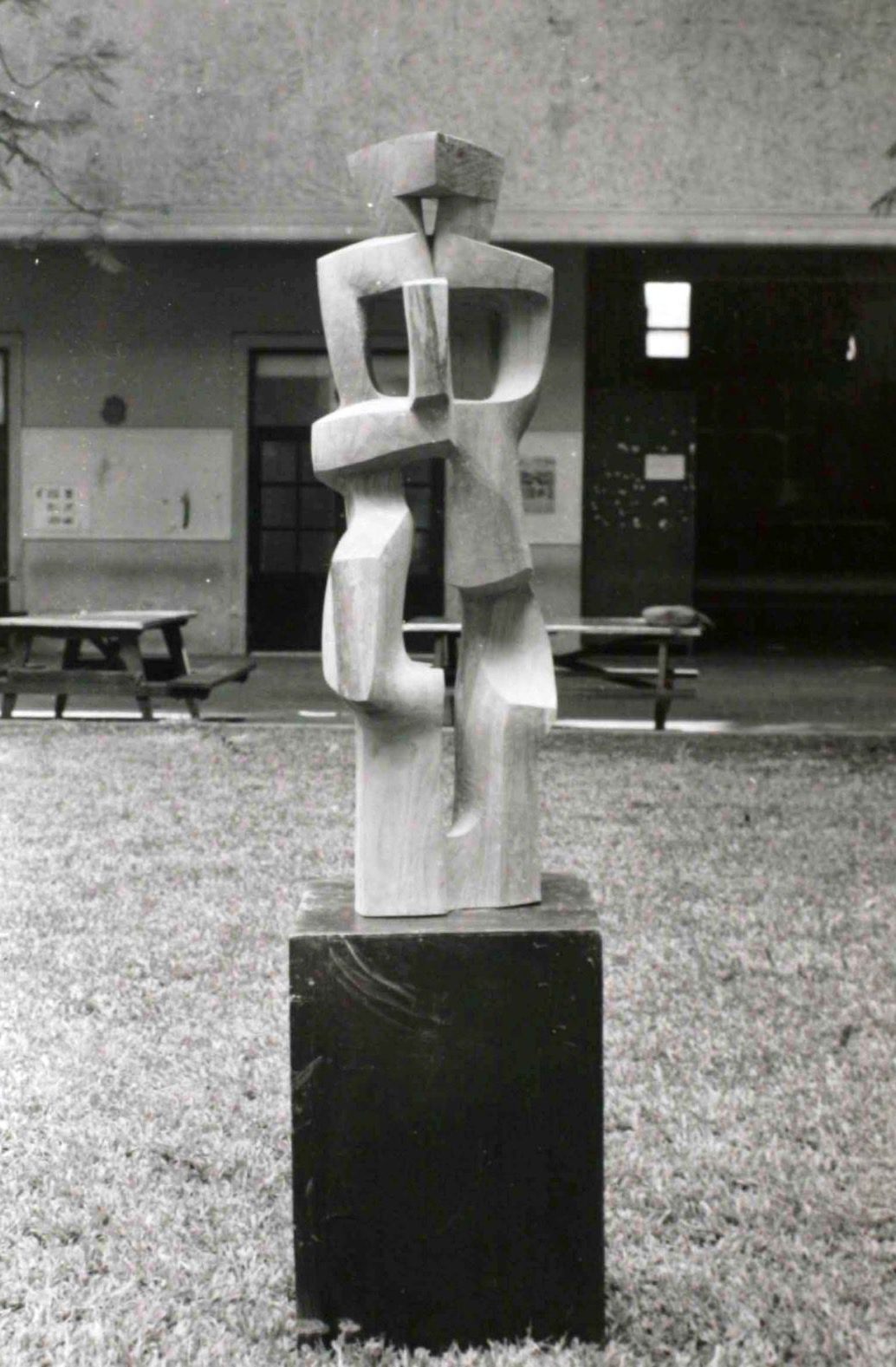

Photo courtesy of Peerapong Doungkaew

art4d: As I understand, after you entered Silpakorn University, your interests expanded across various fields such as anthropology, archaeology, history, sociology, and even folk art in recent years. You also had the opportunity to study abroad in Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Could you share what you were searching for at the time and what you discovered that made you feel, ‘Yes, this is who I am’?

PD: When I first began my studies, I had quite a narrow perspective. At Silpakorn, I followed a curriculum shaped by Professor Silpa Bhirasri’s approach, which blended contemporary art and Western methods of learning. But, at the same time, I was surrounded by Buddhist sculptures and other cultural symbols. This curriculum truly ignited my passion for the art histories of both the West and the East, including art criticism. It exposed me to a broad range of aesthetic knowledge, including painting, sculpture, printmaking, and even music. Professor Silpa even incorporated music into his teachings, allowing me to absorb both Thai and Western music, which in turn broadened my appreciation of aesthetic diversity.

After graduation, I felt the need to experience art in its true context, so I traveled to Italy and Europe. Later, I exhibited my work in the United States, staying with Professor Kamol and traveling across the country for a month. This experience exposed me to the contemporary art movements in both America and Europe, further enriching my understanding of the global art scene. It was during this time that I began to see the connections between Eastern and Western art. In my early years, I was heavily influenced by Western styles, such as Modernism and Cubism, and I eagerly followed those trends. My early works reflected this excitement and desire to be part of the modern art movement. However, over time, I realized that I needed to explore Southeast Asia. This led me to teach at Payap Technical College, where I taught anatomy and art history. These subjects required me to study both Western and Eastern art histories, as well as the art of Southeast Asia.

Later, when I moved to Chiang Mai, I continued teaching and began researching the local art and culture of Northern Thailand, its way of life, traditions, cuisine, and the religious art in its temples. Even though I am from Isan, I found great inspiration in Northern Thailand. I began to see how Isan art and Northern Thai art shared a similar folk aesthetic. This discovery helped me reconnect with my roots and incorporate those influences into my work.

art4d: In your early works, we noticed that each piece had very long titles, such as ‘The Hidden Power That Maintains the Balance of Forms and the Relationship with the Void of Air 2’ or ‘The Continuity of Mass Volume in Relation to the Space of Air,’ and even ‘True Standing Form.’ I’m curious, what were you searching for at that time? These works seem completely different from the direction your art takes today.

PD: Back then, it was all about Western modern art. Everyone was following that trend. The influence of Western art was very strong, and it was definitely modern. At the time, I was influenced, but I was just a kid who didn’t fully understand it fully. My professors would warn me not to blindly follow the West, but during my studies, I wanted to be Western, I wanted to be modern. So, I made work in that style, creating pieces inspired by Henry Moore, adopting a Constructivist approach, exploring the relationship between space and form. It was abstract, or semi-abstract. I would go to libraries or travel abroad, visiting museums like the Museum of Modern Art in America.

art4d: During that period, they would pour buckets of paint on the street.

PD: Yes, exactly. Jackson Pollock and others. But eventually, I moved away from that. I began searching for my roots. I read books on archaeology, studying ancient artifacts. I saw the remnants of our past, tracing it back to our origins. I traveled to Ban Chiang, sailed down the Mekong River from Chiang Saen to Luang Prabang.

art4d: With the strength of Western education in those areas, it must have been difficult to break free from it. Given that you excelled in that direction, it must have been hard to move away, especially with some of your works showing strong symmetry, which Westerners appreciate.

PD: I knew Westerners liked it because that’s what they appreciated, and I understood that. They didn’t care much for the intricate patterns. When I saw that they liked it, I got excited.

Photo courtesy of Peerapong Doungkaew

art4d: Sometimes, that resulted in a more ornamental style.

PD: Besides the ornamentation, it was also about the spiritual essence of the East. I went to Tibet, Nepal, India, and saw places like Khajuraho, Gupta, and Ajanta. I encountered the essence of the East. If I followed the Greeks, it would lead to Cubism.

art4d: If your works were to be displayed at MOMA or any museum, their value would be extremely high. Yet, you chose a simpler life.

PD: Because that wasn’t the path my life took. If I had stuck around and settled in New York, I might have gone down that route, but I didn’t.

art4d: It seems like it could have been a ‘rich and famous’ path, given your skills and understanding of the market. The path of art collectors back then was often along these lines.

PD: Yes, like the late Chawalit, who lived in the Netherlands. He became known for his abstract work, but that was because he chose to live there. I, on the other hand, chose to stay here and live my life the way I am. I have no shame in that. And over time, my confidence has grown. When I’m out of the country, it’s like I bring myself with me.

Photo courtesy of Peerapong Doungkaew

art4d: We’re interested in your early work, particularly when you were focused on woodcut. We noticed that you gave great importance to form, alongside the internal feelings you infused into the work. Could you elaborate on the relationship between these aspects, in terms of expressing emotion and life experiences? Were there any particular messages or elements you wanted to convey through your work?

PD: Of course, art is all about creation. It involves abstraction, semi-abstraction, and even semi-realism. During the modernist period, we were trying to move away from recognizable symbols, and searching for simplified forms. We explored the relationship between space and form, proportion, rhythm, and texture. We were seeking the beauty of artistic elements to create three-dimensional sculptures, which is rooted in the theory of aesthetics. I took what we observed as harmonious and removed the literal, leaving the abstract beauty and allowing it to connect.

But later on, I started incorporating more tangible elements; stories from the Jataka, the way of life, traditions, and the essence of the Lanna culture. These became integral parts of my work. It became more subjective, blending personal experience into the art. The storytelling aspect is something that Thai people, or people in general, can easily relate to. When I teach, I have to communicate these ideas with my students. But when I’m feeling tired or uninspired, I’ll return to abstraction. It’s a natural back-and-forth. The balance between these styles is a normal part of the artistic process, and I still don’t know how much of each I’ll carry forward, or how much I’ll return to.

art4d: In terms of art history, which artists do you think stand out most when it comes to blending feeling and form?

PD: Vichai Sithiratana, Nonthivathn Chandhanaphalin, and Khemrat Kongsook all stand out in their ability to combine feeling with form, especially in abstract work. But Vichai, he also still carves Buddhist statues beautifully.

art4d: Let’s talk about ‘Tree of Life,’ which is a sculpture of a tree, and I feel it has a very rural essence. It carries elements of local culture, a sense of aridity, and a very clear atmosphere of folk traditions. What were you aiming to communicate through all of this?

PD: This piece reflects a story I’ve blended from the cultures of Isan and Southeast Asia more broadly. It started when I observed the way of life. There’s endurance and hardship, but also the Mekong River, which is the cradle of traditions, the livelihood of the people, and even the cruelty they’ve faced.

I wanted to reflect all of this through the intensity of the forms, the traditions, and culture. I used birds as symbols, as we often see birds perched in temples or shrines, representing heaven, the divine, or the transcendent. I wanted to connect this symbol of birds to faith and belief, and also to the idea of the propagation of plant seeds as well.

I spent two years creating this series, focusing on themes of biodiversity, reproduction, and abundance. Today, our land is drying up, it’s no longer fertile, and the excessive use of pesticides is taking its toll. We also face natural disasters; floods, earthquakes, and other shifts in our geographical landscape.

art4d: When all of these works are displayed together, do they tell the story of the local environment you studied and researched?

PD: The theme of propagation, of spreading plant seeds, is something I observed closely. There are various symbols within it, like leaves that aren’t just leaves but units of cells dividing, forming a family-like structure, interconnected like a network. When you look closely, it seems as though it’s undergoing photosynthesis, as if the leaf is turning to catch the light to help the cells divide and expand. When you ask why I include biology or other elements in my work, it’s because creating art requires research, not just personal emotions.

art4d: This approach is different from the period when art was purely about inner emotion, translated into form to express feelings. Now, it’s become more research-based, with a scientific dimension, compared to the pure art you grew up with.

PD: Exactly, it’s academic. In fact, art and academia should connect in a balanced way. If you look back, it’s similar to Jackson Pollock’s work, where he splashed paint. That’s pure emotion, entirely driven by feeling.

art4d: For someone unfamiliar; a few spots of color, like something by Cy Twombly, might be shocked by its incredible price.

PD: Yes, it can go for hundreds of thousands or even millions. There were even people who joked that they could bring elephants to paint, using brushes at the elephant camp, and call it abstract art, then auction it off. If someone wants to call that art, fine, I don’t mind. But if you study it closely, there’s always a deeper context behind it.

art4d: How is your daily life these days? We notice that you live a very simple life, mostly working and resting.

PD: That’s right. My life and work have become one and the same. The reason I moved from Wualai Soi 4 area is that it was a community known for silver-making, and I had been immersed in that kind of culture for some time. But I couldn’t work on my art there because I needed a quieter space. Now, I have freedom, and I can focus entirely on my work. My sole focus is to create art without distractions. I don’t do it to become rich or famous. I do it because I love art, and I want to see my thoughts come to life. I want to see how the ideas I have will manifest as tangible works of art, and how they can be experienced. That’s all.

When I have artist friends who invite me to do art projects in places like India, Malaysia, or Japan, I bring my tools along. I find joy in that process. After returning, I live in a small hut with nothing much around. I sleep on the floor because I have nothing to worry about. If I did, I’d worry whether others might have to struggle the way I do, so it’s better not to let them come too close. Living like this has allowed me to focus more deeply on my work. I have freedom and the desire to create more. And I can take care of myself without any problems.

art4d: As a sculptor with extensive experience, do you have any thoughts on the current art scene?

PD: Contemporary art is incredibly diverse, and I truly admire it. Art now holds significant importance in communities, and people increasingly recognize it as a part of their lives. In the past, it wasn’t always like this, but the world has developed, and now art and artists come in all ages. The art of younger generations reflects their ideas, shaped by the environment they live in. As for older artists, they continue to work, and I think it’s great that we still have both veteran artists and those near the end of their careers still creating. Meanwhile, younger artists are producing more varied work, and audiences now have access to a wider range of artistic expressions.

At its core, this reflects abundance; the flourishing of beauty. Art is something everyone contributes to, something that fosters growth and doesn’t harm anyone. When it’s created, it enriches society. Art and culture are what elevate us above animals. We see the value of truth, goodness, beauty, subtlety, and emotion. When we encounter something bad, it moves us, and if we’re not focused on money, it could mean we’re driven by some greater ideal. Imagination, in turn, generates beauty that we can experience, and it helps us evolve as human beings.

The cultures of Greece, Rome, Sukhothai, and Ayutthaya all emerged from the intertwined forces of art, economics, and society. Everything is connected. Even today, many institutions recognize that art is essential. In times of economic strength, we see museums and children’s museums thrive, along with programs that encourage learning through play. Such experiences not only relieve stress but also nurture the growth of a child’s mind. When children engage with art and come to understand it as a vital part of life, it cultivates an inner richness, fostering imagination and shaping them into well-rounded individuals. As they grow, this foundation allows them to expand into any field, from technology to the sciences. Professionals in fields like medicine and engineering also benefit from making art, as it sharpens their creative thinking. In the end, everything is connected. We all contribute in our own way, and that’s a good thing.

‘Tree of Life,’ a solo exhibition by Peerapong Doungkaew will be held from today to 31 August 2025 at MATDOT Art Center.