ARCHITECTS JENCHIEH HUNG AND KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE OF HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH EXPLORE SHANGHAI’S LONGTANG, TRADITIONAL SHARED OPEN AND DEAD-END ALLEYS

TEXT: JENCHIEH HUNG & KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE

PHOTO: HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH

(For Thai, press here)

Born out of intricate urbanism, dead-end alleys, dubbed as cul-de-sacs, were spaces where the boundaries between public and private life are blurred. These alleys serve as vibrant, flexible spaces where daily activities foster community interaction. These alleys use everyday objects not only as utilitarian items but also as tools to define private boundaries while maintaining a strong sense of communal living, as featured in their latest book, Chameleon Architecture: Shifting / Adapting / Evolving

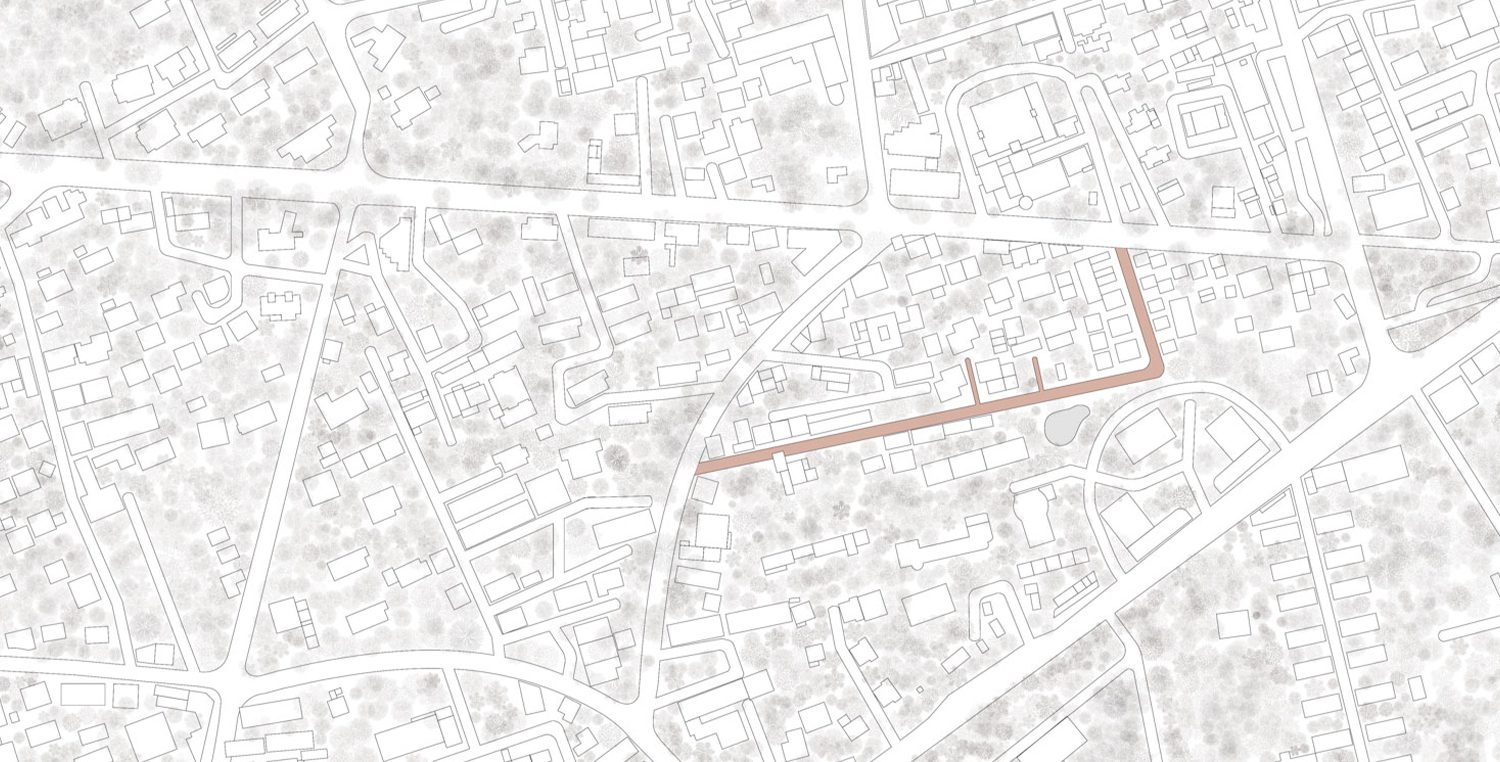

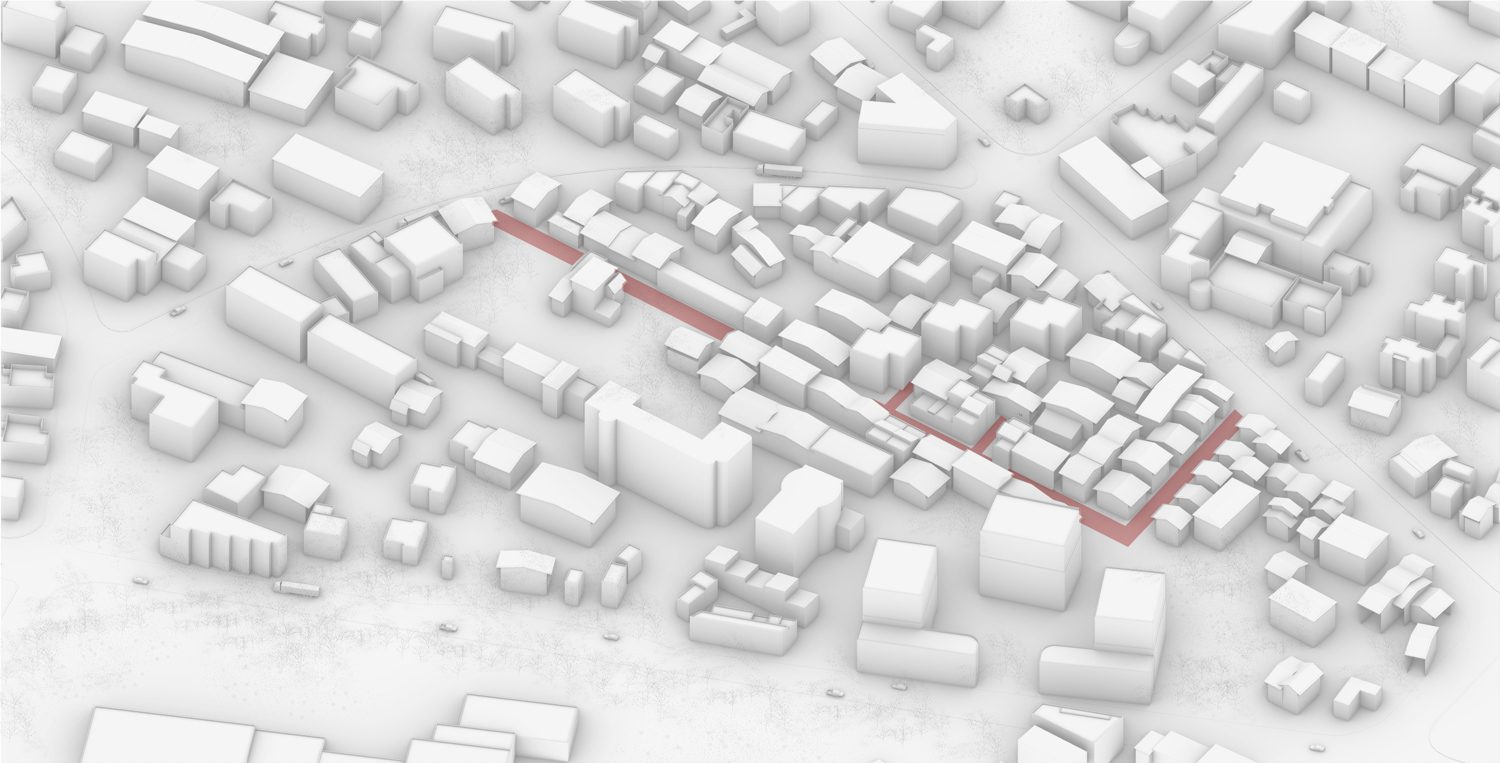

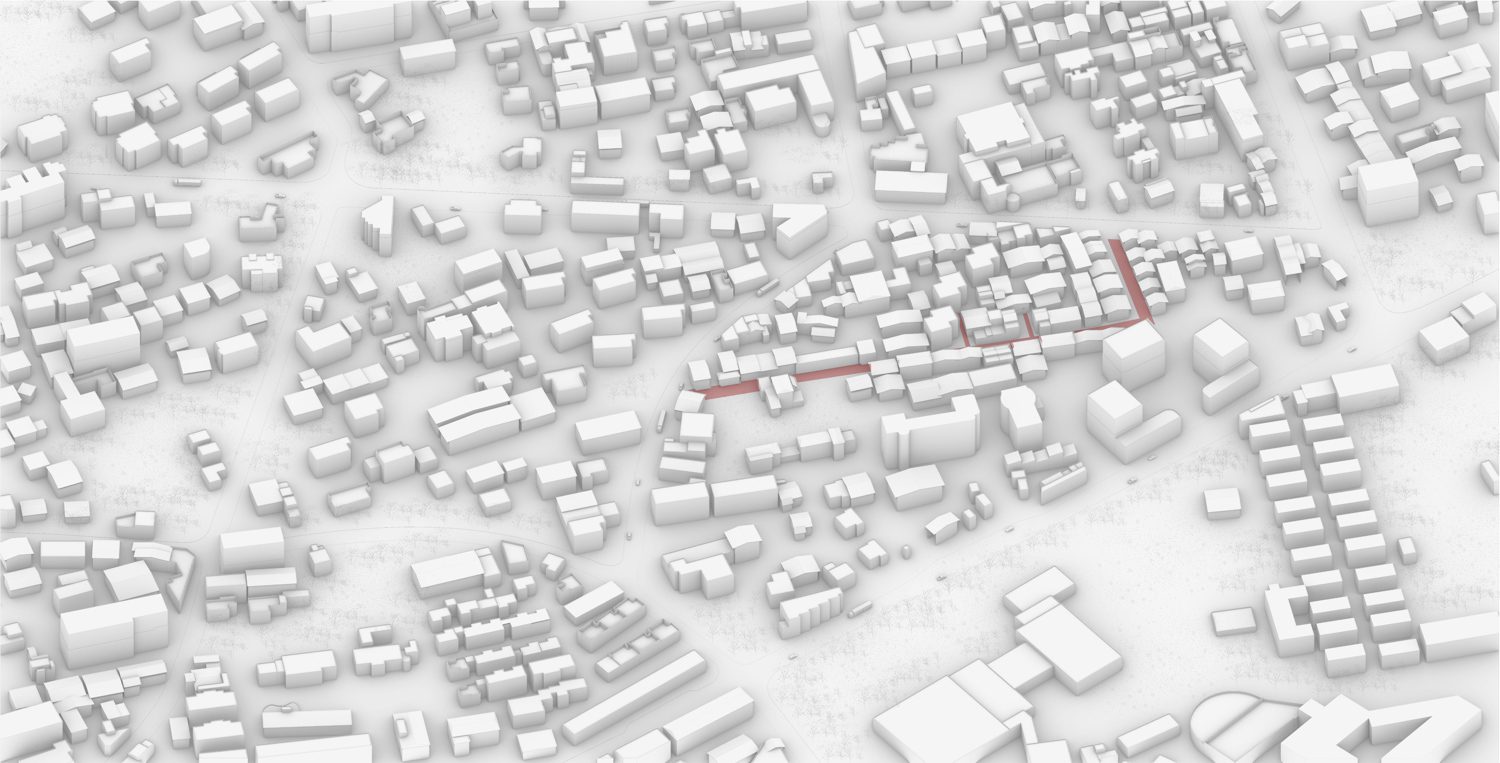

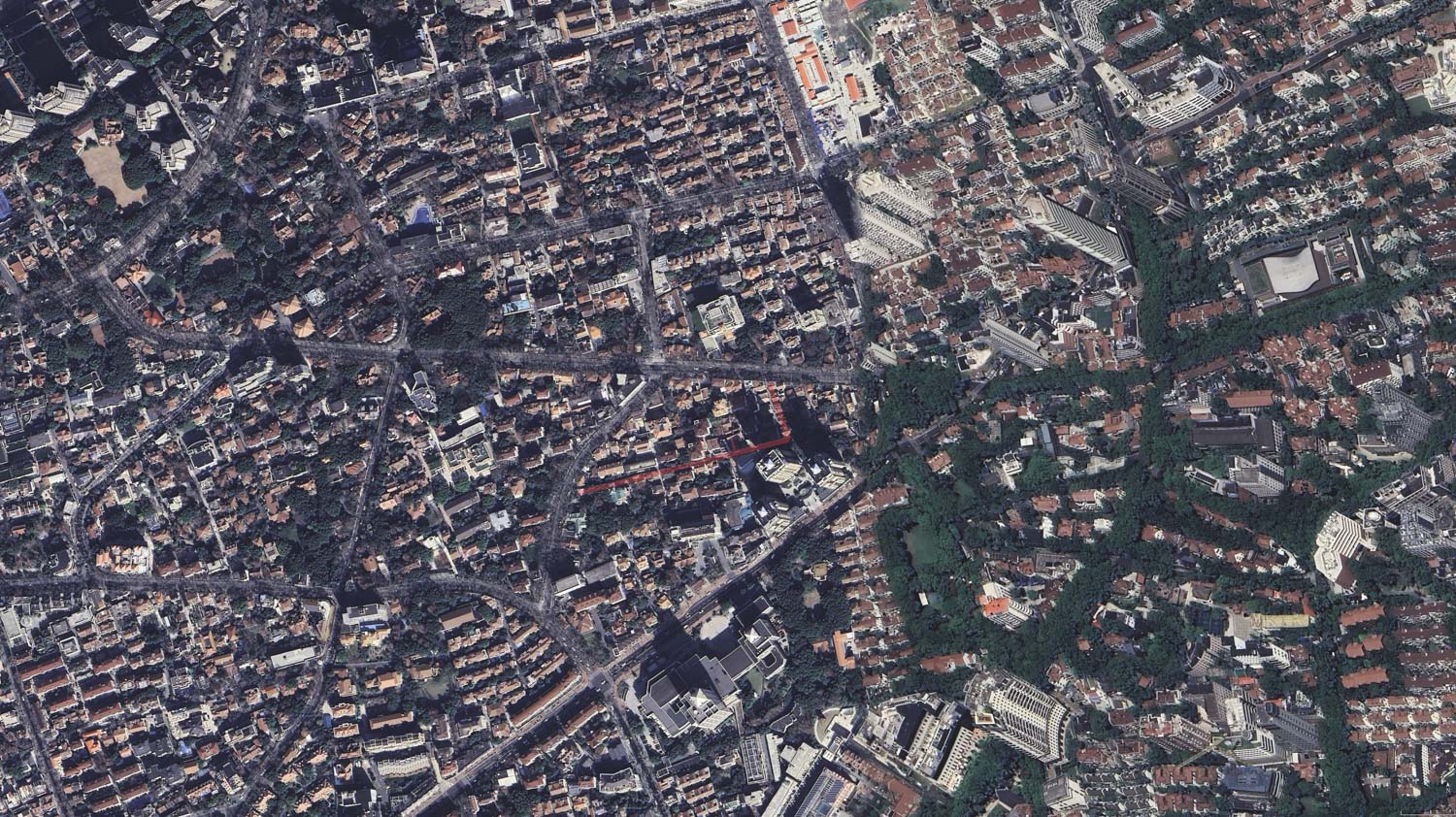

Shanghai is a vibrant metropolis where modernity and tradition coexist, often in unexpected ways. Amidst towering skyscrapers and rapid urban development, the city’s traditional alleys, known as Longtang, remain integral to its identity and cultural heritage. These alleys, though small and winding, are more than physical passages; they are living spaces that carry memories of the past while continuing to foster social interaction and communal life in the present. Architects Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee of HAS design and research explore the cultural significance of Shanghai’s shared open/dead end alleys, examining how they blur the boundaries between private and public spaces, contributing to the city’s dynamic urban fabric.

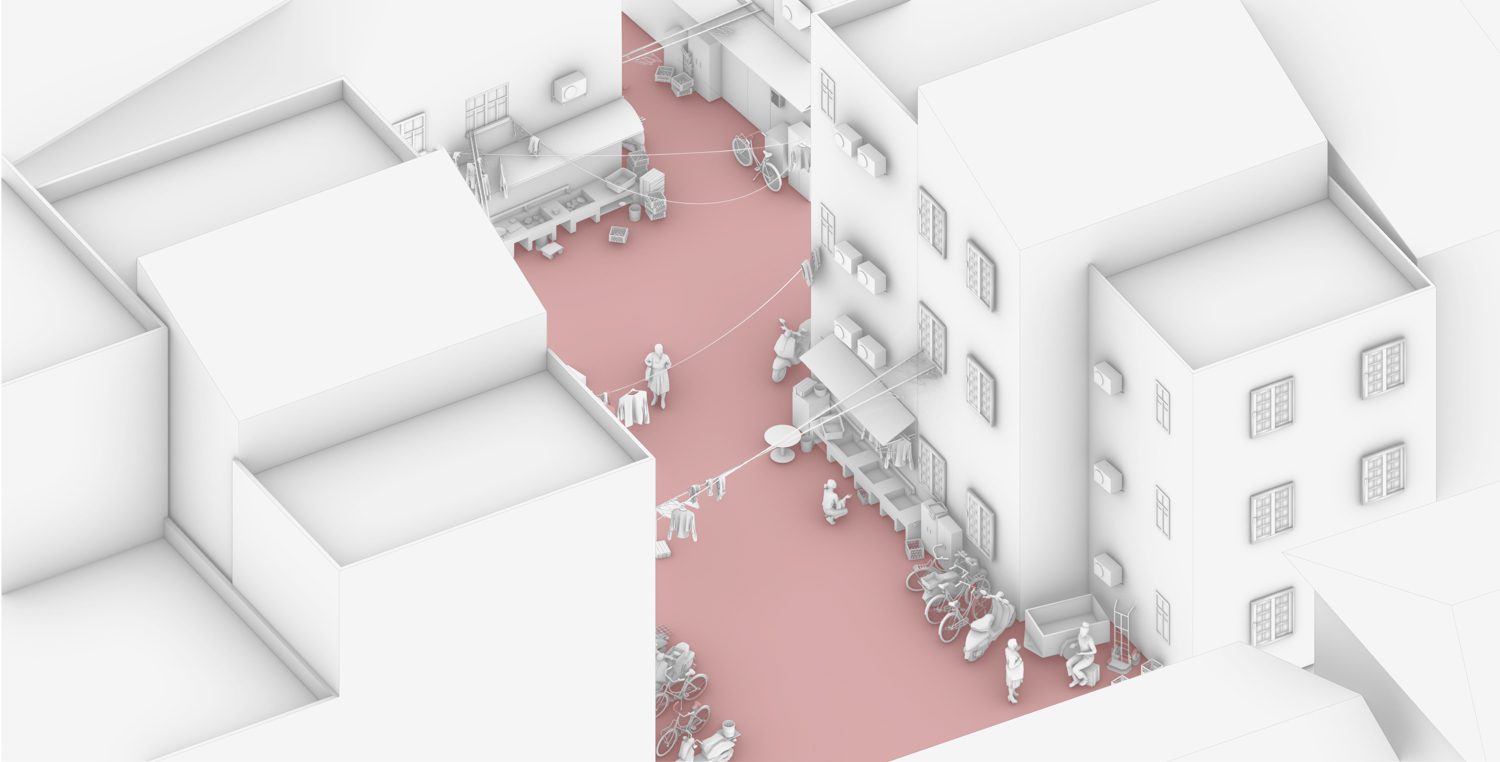

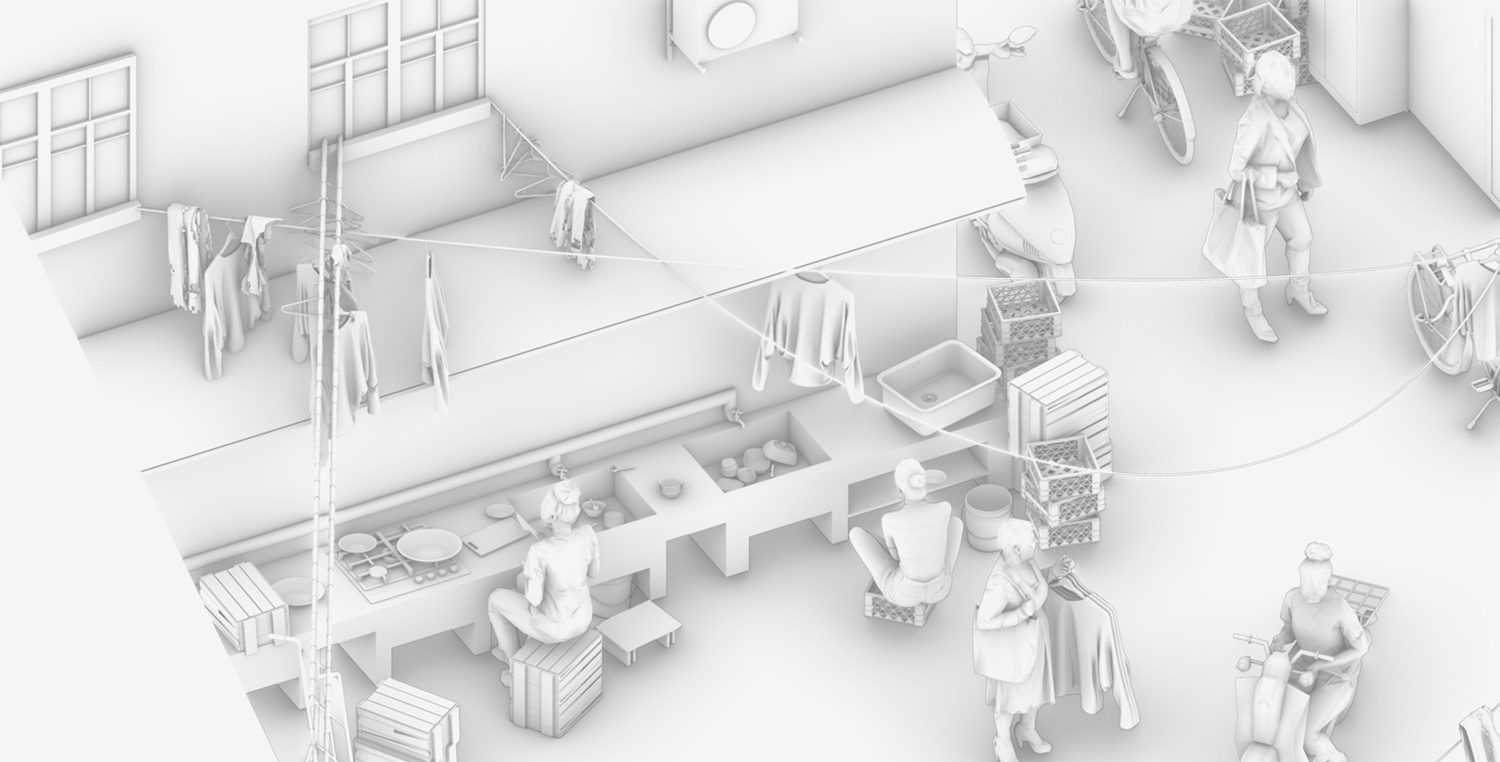

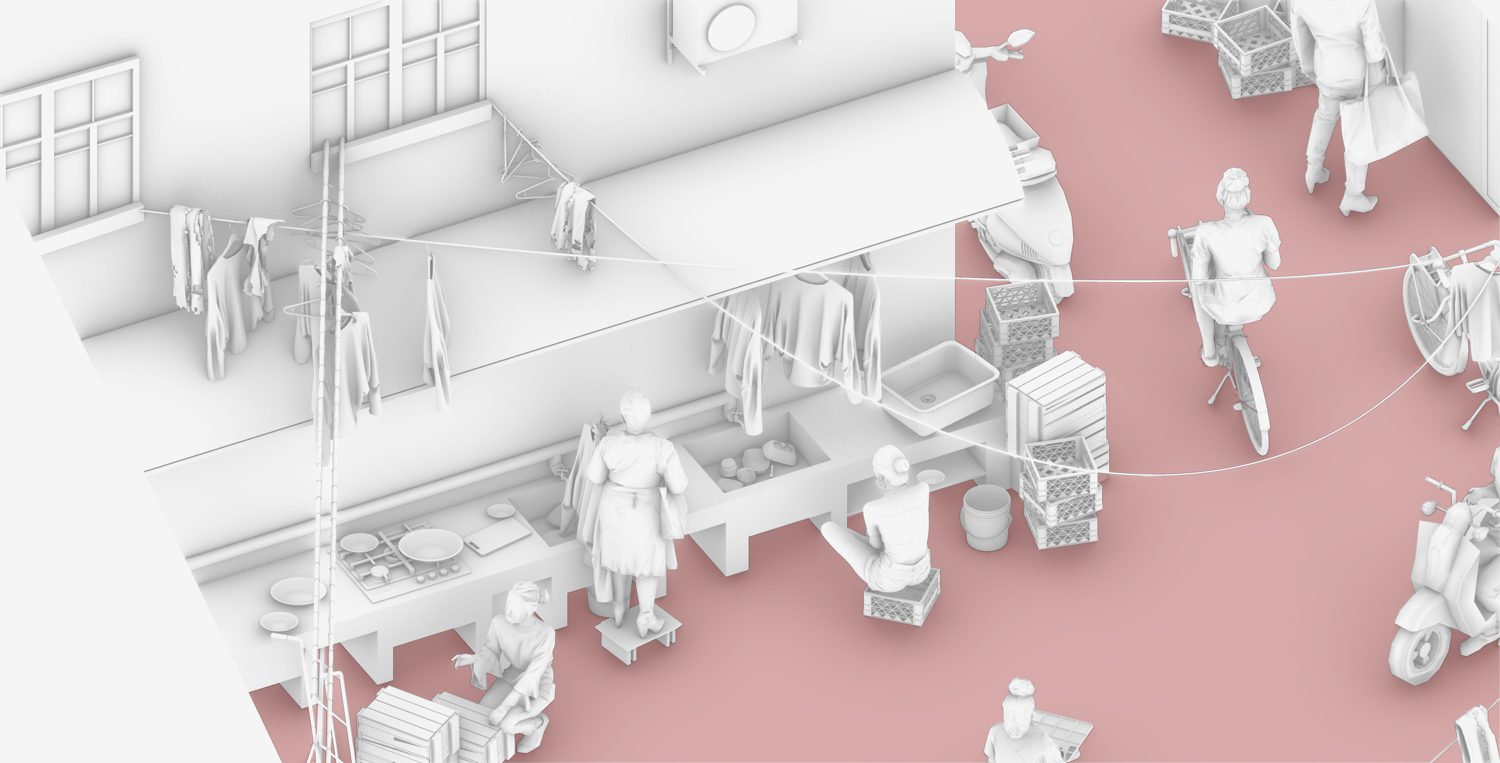

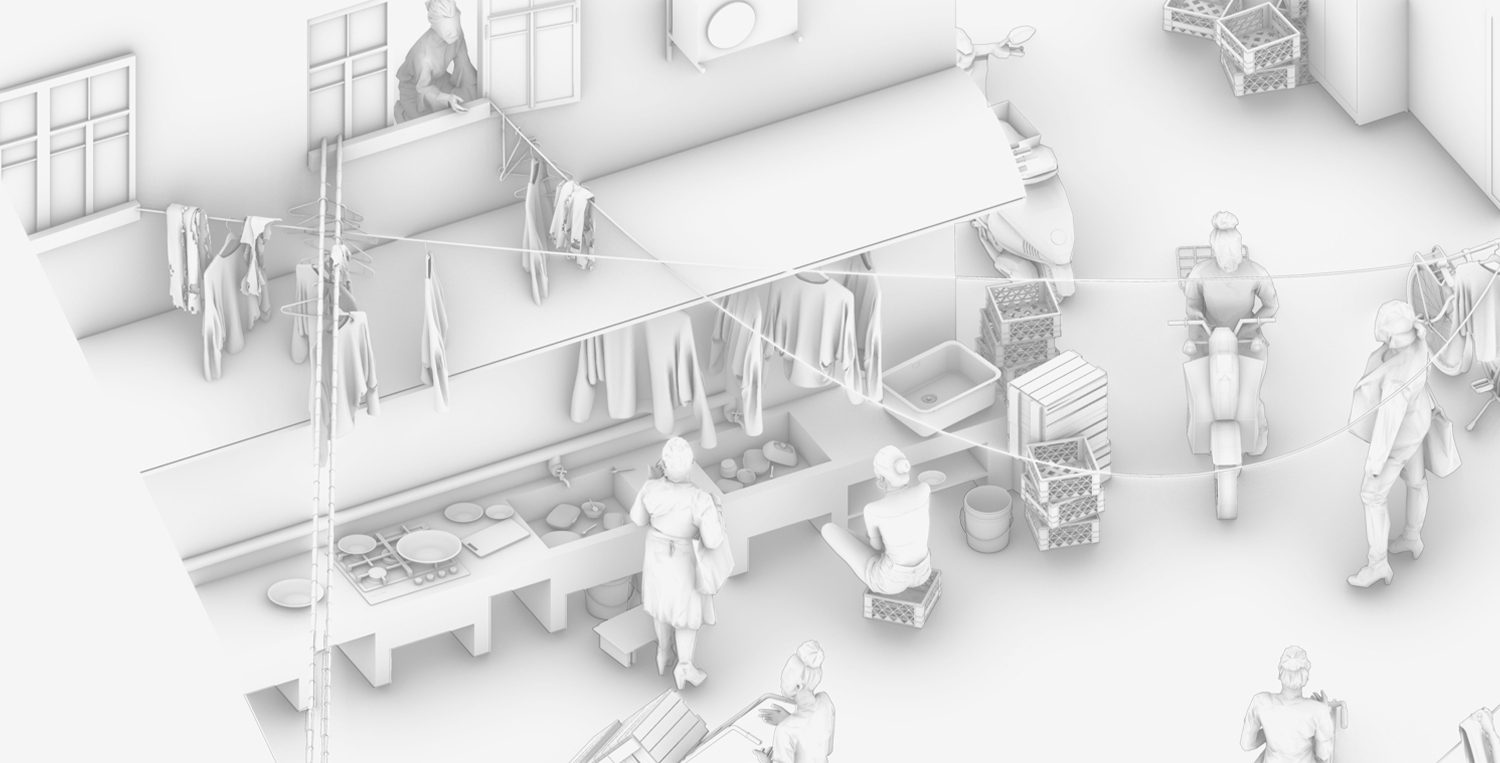

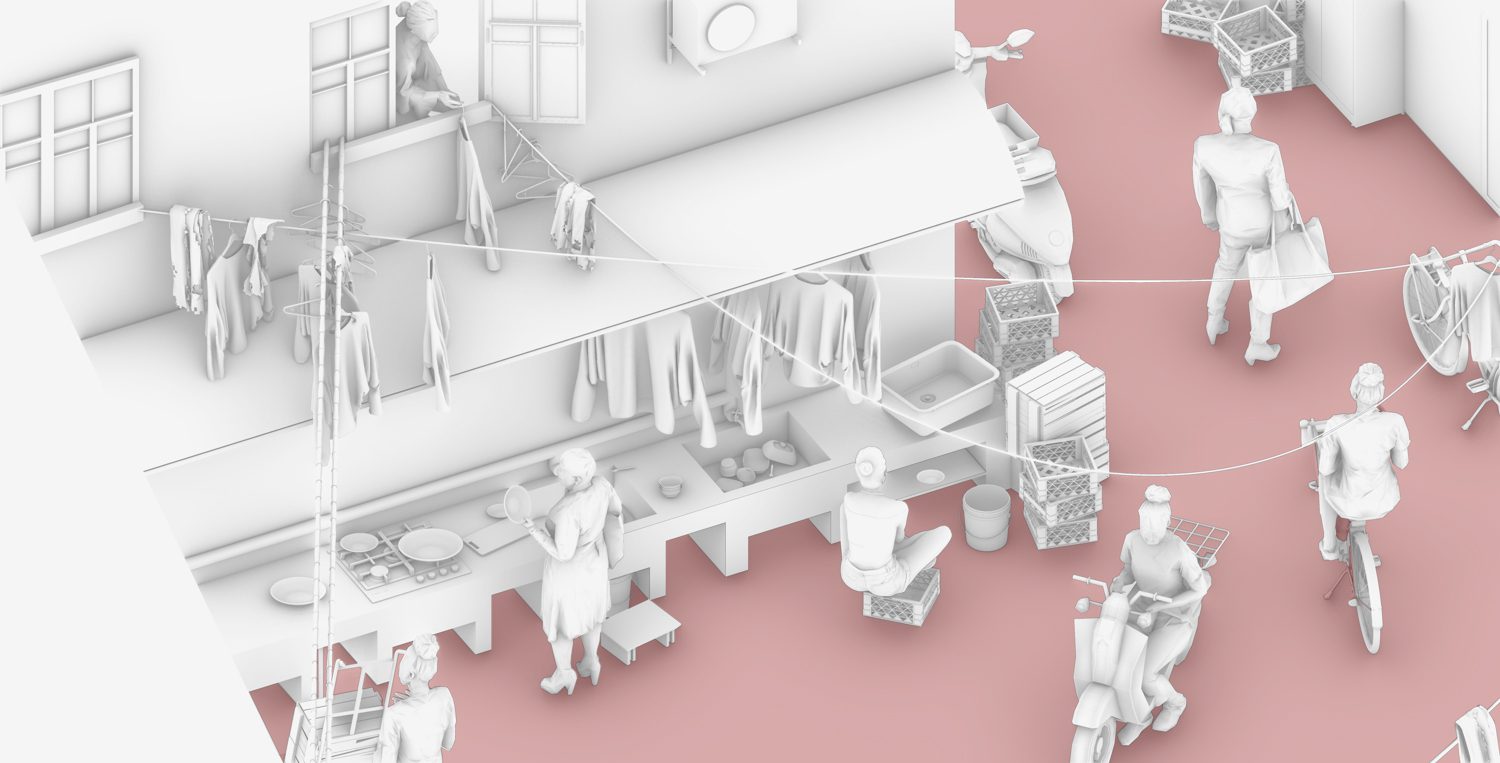

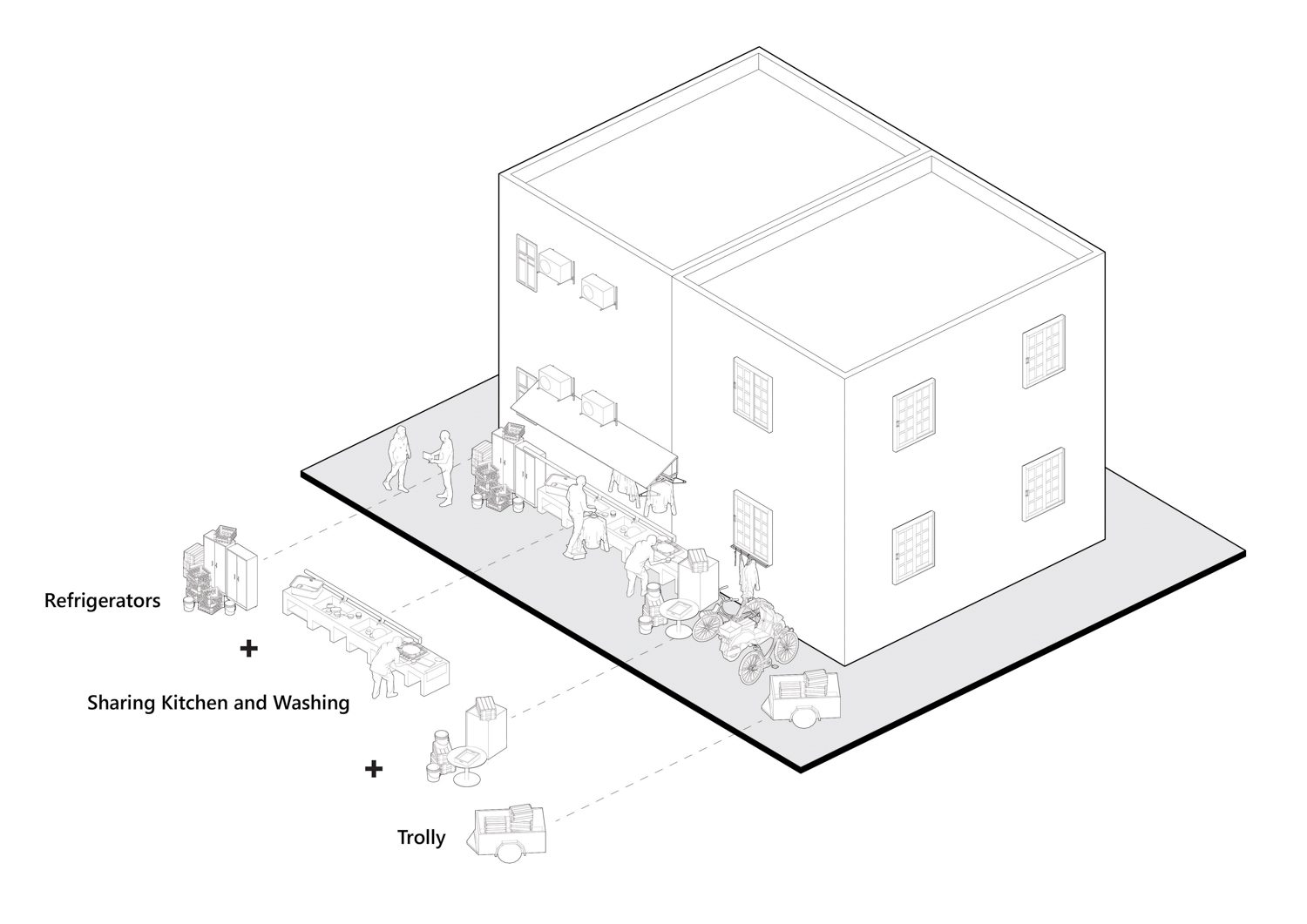

Longtang alleys are far more than remnants of Shanghai’s past; they represent a living continuum of the city’s historical culture. Despite the urbanization surrounding them, these alleys serve as spaces where daily life unfolds in ways that high-rise buildings cannot. Activities such as washing clothes, drying garments, playing cards, chatting with neighbors, and even cutting hair occur within these public spaces. The dimensions of these alleys, typically between 4 to 6 meters wide, create an environment conducive to interaction, fostering a community-based lifestyle that contrasts with the isolation found in more private spaces. Shanghai’s alleys stand apart from those in other Asian cities due to their distinctive, meandering layouts. Rather than ending abruptly, Shanghai’s alleys often lead to open spaces like courtyards or community hubs, enabling more fluid transitions between private and public spheres. These courtyards, typically found at the end of the alleys—also known as dead-end alleys—function as dynamic urban spaces, hosting community service stations, neighborhood communication centers, and informal meeting areas. Far from being mere passageways, they transform into places where people gather, communicate, and engage in collective activities.

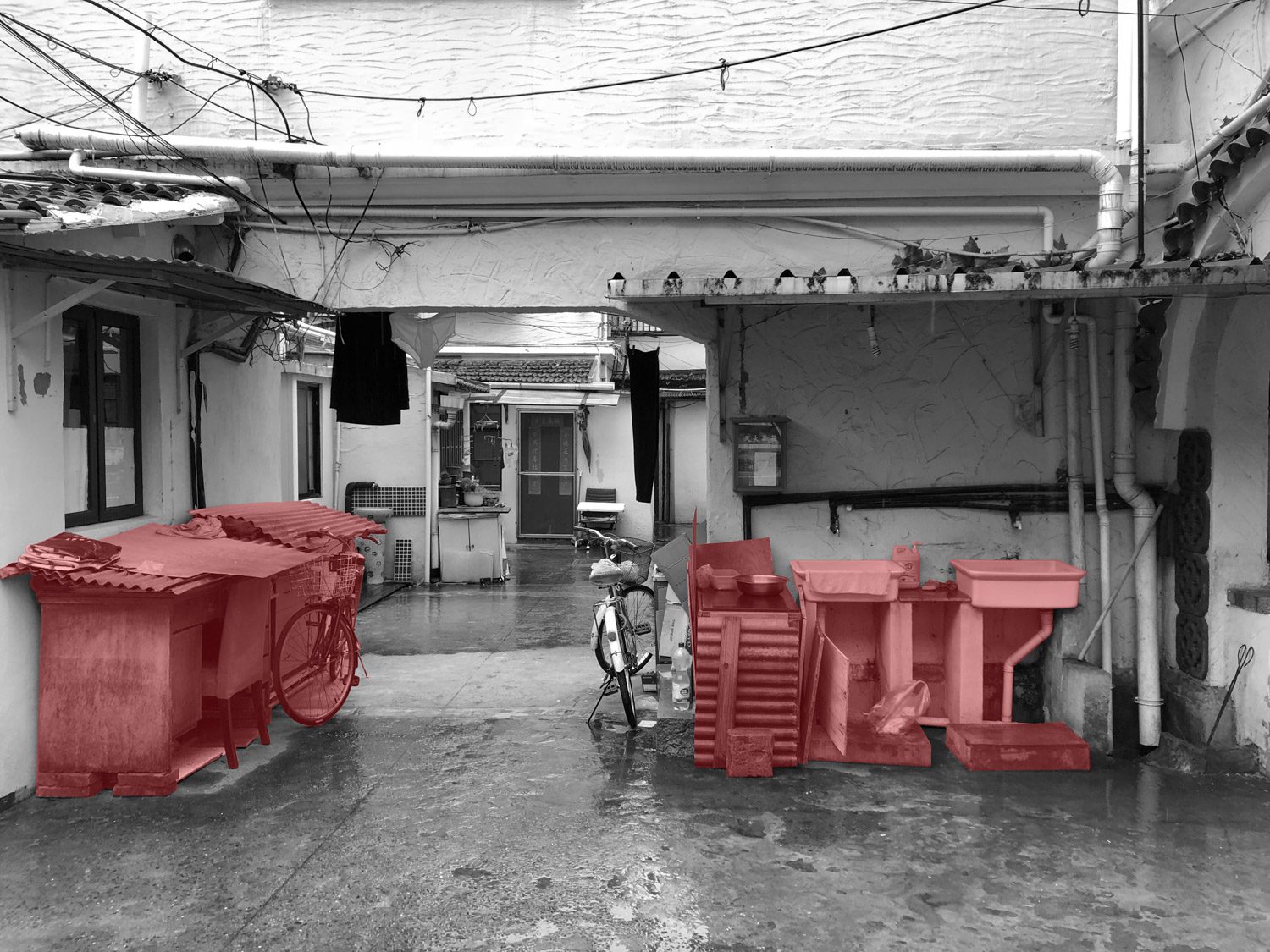

One of the most intriguing aspects of Shanghai’s longtang alleys is the way they blend material culture with social spaces. Everyday objects such as washbasins, brooms, wooden fences, and potted plants are more than utilitarian items; they help define and demarcate private boundaries. The placement of shoes outside a door, potted plants along fences, or even cabinets against alley walls serves as a subtle but effective means of marking personal space while preserving a sense of communal living. Arranged in specific ways, these objects establish informal divisions between households, creating a fluid, adaptable environment where privacy and social interaction coexist. Unlike new urban spaces, which often impose rigid separations between private and public areas, the organization of Shanghai’s alleys embraces a more flexible, less definitive approach to boundary making.

This flexibility in spatial boundaries is a defining feature of many Asian urban spaces, including those in Thailand, and one that people actively seek. In Shanghai’s alleys, the boundaries between private and public are not fixed but are continuously negotiated through daily activities and interactions. The alleys function like the city’s capillaries, serving as shared spaces that allow informal exchanges, mutual reliance, and at the same time, assert a sense of ownership over the surrounding area. Together, they form a system that breathes life into both the people and the city. The integration of flexible boundaries and shared spaces can help create cities that prioritize human connection and preserve cultural heritage amidst modernity. In this way, Shanghai’s shared open/dead-end alley is not only a window into the past but also a vision for a more connected and inclusive urban future.

This article content is an excerpt from the book ‘Chameleon Architecture: Shifting / Adapting / Evolving,’ authored by Jenchieh Hung & Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS design and research, available for purchase at: https://art4d.com/product/chameleon-architecture

facebook.com/hasdesignandresearch

instagram.com/has.design.and.research