‘REMNANTS OF FADING SHADOWS’ IS AN INSTALLATION THAT EXPLORES THE BOUNDARIES OF MEMORY, THE NEAR AND THE DISTANT, AND THE INCOMPREHENSIBLE

TEXT: KANDECH DEELEE

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

A ripple of doubt emerges within the microcosm, spilling forth from previously seamless fractures. It strikes against the edges, swelling and expanding, forming an instability that feels weightless yet impossibly heavy. The familiar begins to tremble. Its surface quivers, undulates, and is ultimately shaken to its core.

Remnants of Fading Shadows by Wantanee Siripattananuntakul explores the convergence of memory and history. Beginning with intimate, personal narratives, the artist allows these stories to guide her inquiry, gradually revealing how the seemingly closed realm of familial memory is deeply entwined with the open terrain of politics. Her work serves as both as a link in the chain of transmission and creation, and as a metaphorical lens through which personal stories emerge as a microcosm resonating in sync with the ever-orbiting universe of history.

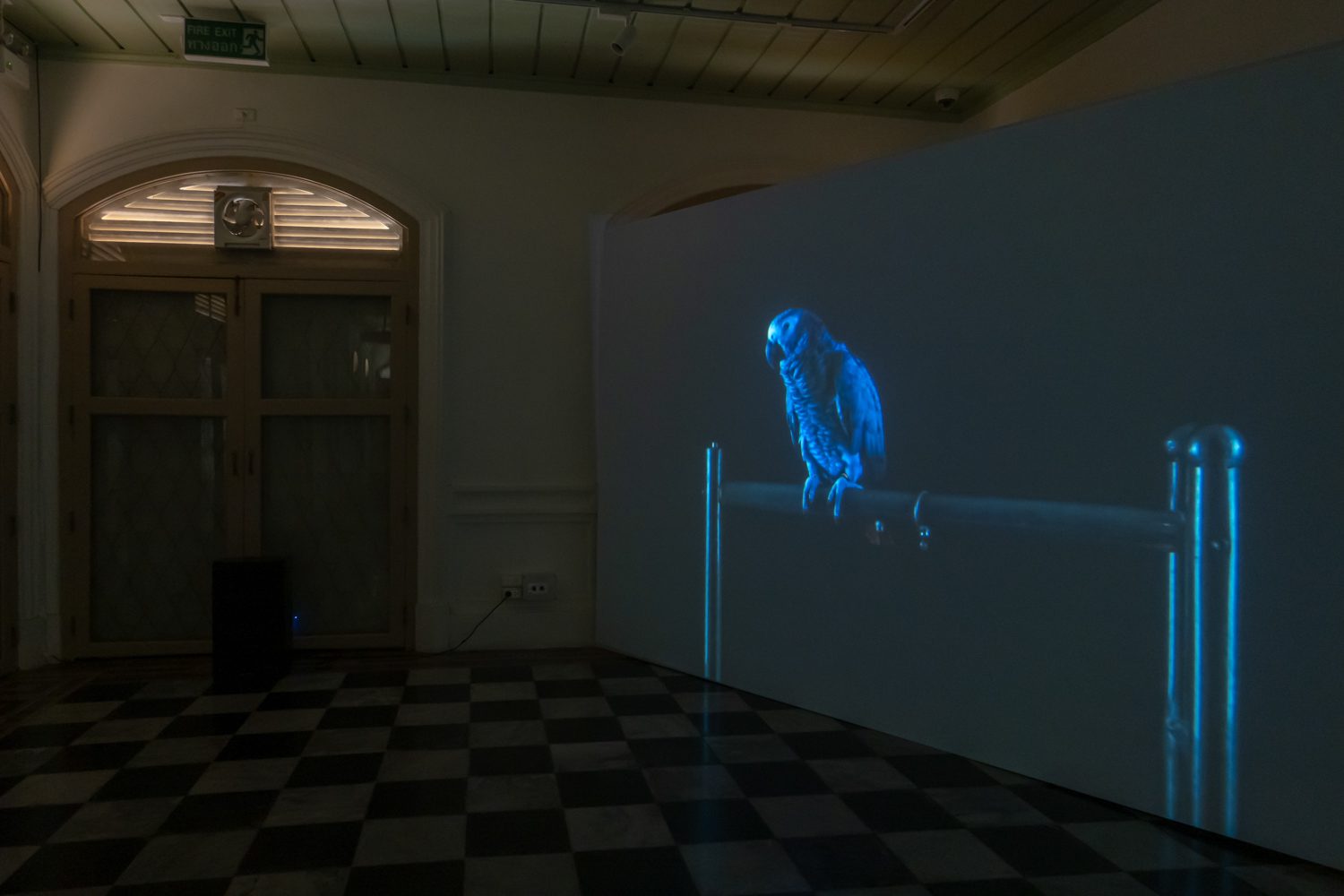

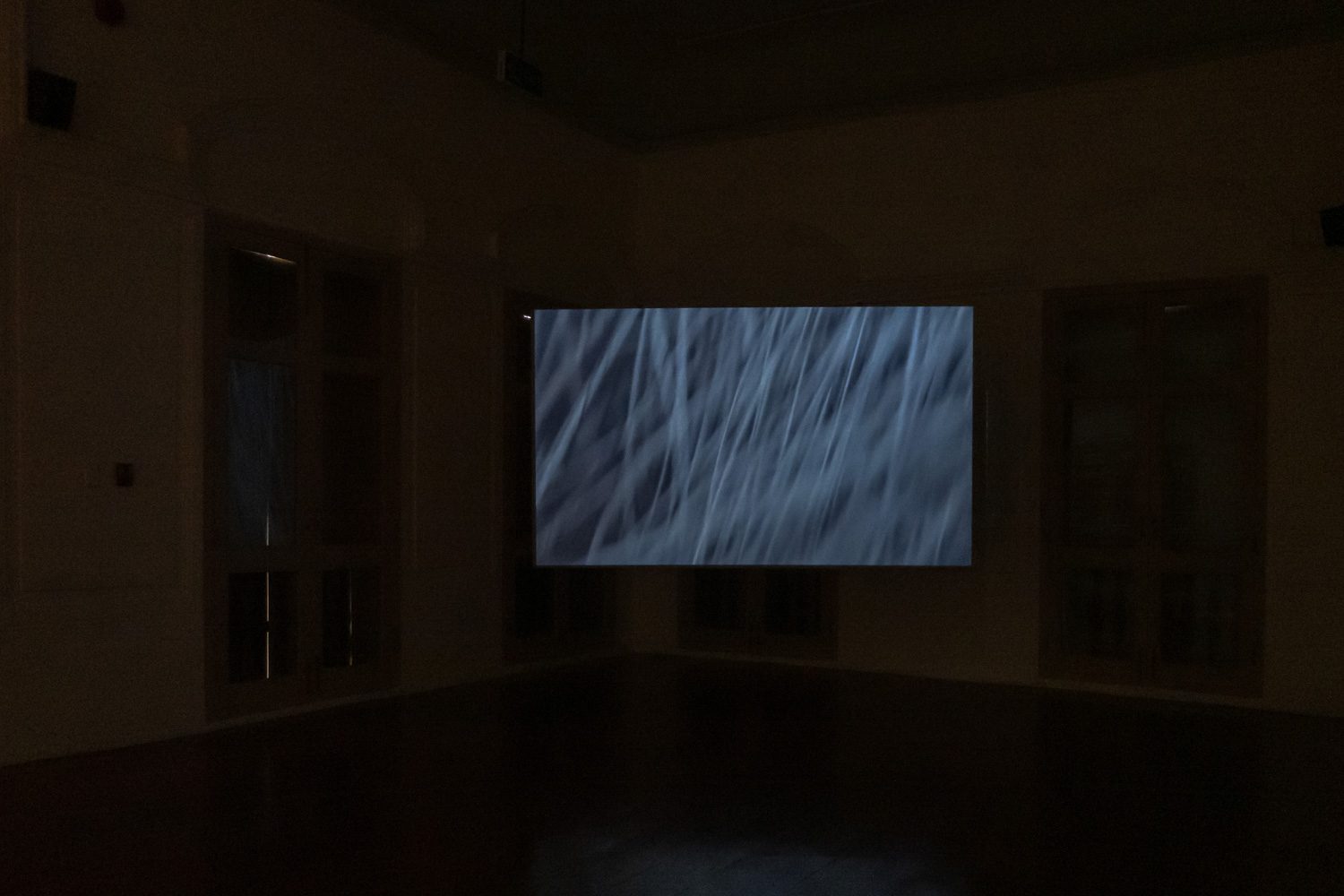

And yet, despite Wantanee’s tendency to weave narratives from small, seemingly disparate details, it is the surface that emerges as a recurring motif throughout her work. The surface of a given subject is brought so uncomfortably ‘close’ that the whole form vanishes. Proximity becomes disorienting, producing a sense of estrangement rather than intimacy. In Making the Unknown Known (2023), a three-screen video installation features the Mekong River landscape, an elephant1, and an African Grey parrot. The work opens with an extreme close-up of the elephant’s skin. Wrinkled textures and fine, shifting hairs fill the frame, animated by the elephant’s subtle movements and the camera’s own. This visual entry point, while intimate, doesn’t obscure recognition entirely. Viewers can still discern that this is elephant skin. Yet the camera lingers obsessively on its tactile terrain, inviting the audience to remain suspended on the surface for an extended period. Meanwhile, the other two screens provide a sense of visual distance: a parrot perched on a beam, a riverbank exposed by receding water. It is not until nearly halfway through the piece that the elephant’s full form is revealed.

Only then does the pale tone of its skin disclose its identity as an albino elephant. This moment aligns with a closing narration that details the characteristics of albino elephants, whose distinctive skin color is the most notable. What’s striking is that, even after prolonged exposure to the elephant’s surface, viewers are unable to immediately identify it as albino. The very feature that defines the creature; its pale hue, is rendered indeterminate through the closeness of the gaze. Proximity, in this case, does not bring clarity; instead, it strips away certain forms of knowing that might only emerge at a distance.

In The Web of Time (2022), Wantanee intensifies her focus on surface. Following a narrative that weaves together conflicting family histories, human genetic data, and wartime devastation overlaid with the shadow of a bird, she presents a sequence of contrasting textures: the wrinkled skin of a human body, a scalp dense with white hair, animal fur subtly rising and falling with each breath, and the plane of insect-trapping webs stretched across blades of grass. These varied surfaces are placed in deliberate juxtaposition with earlier imagery. Surface becomes something ‘collaged’ with the violence of war, and ‘stitched’ into the disorienting question of ancestral origin, whether it is rooted in the heart of the African continent or, as her father always believed, in the mythic land of the dragon: China.

Three threads—family narrative, political conflict, and surface—intertwine into a layered confrontation. Wantanee’s work does more than reveal entangled political dynamics across uneven terrains; it exhales the emotional residues embedded in the work itself: anxiety, fragility, and the condition of being a small unit caught in a field of confusion and the unknowable. The Web of Time draws viewers into an encounter with the limits of sensory perception and the narrative construction of time. We become tiny insects clinging to the fur of a larger, breathing creature. Our constrained senses perceive it as a landscape, though we may, in fact, be anchored to something alive; something that is ‘still (a) life,’ yet cannot be fully understood.

What lies beyond the frame still exists. One may point and say ‘bird’ or ‘river,’ but if even elephant skin cannot be taken at face value, then what lies outside the bird’s frame, what spills beyond the river’s edge, must also contain something else. Something unreachable, beyond what our limited senses can grasp. Like human beings and history, we are ultimately incapable of fully conquering or understanding anything in its entirety. We inhabit surfaces we cannot truly penetrate, defeated by the horizon of vastness. We grasp only what is near, and all too often we mistake that nearness for totality.

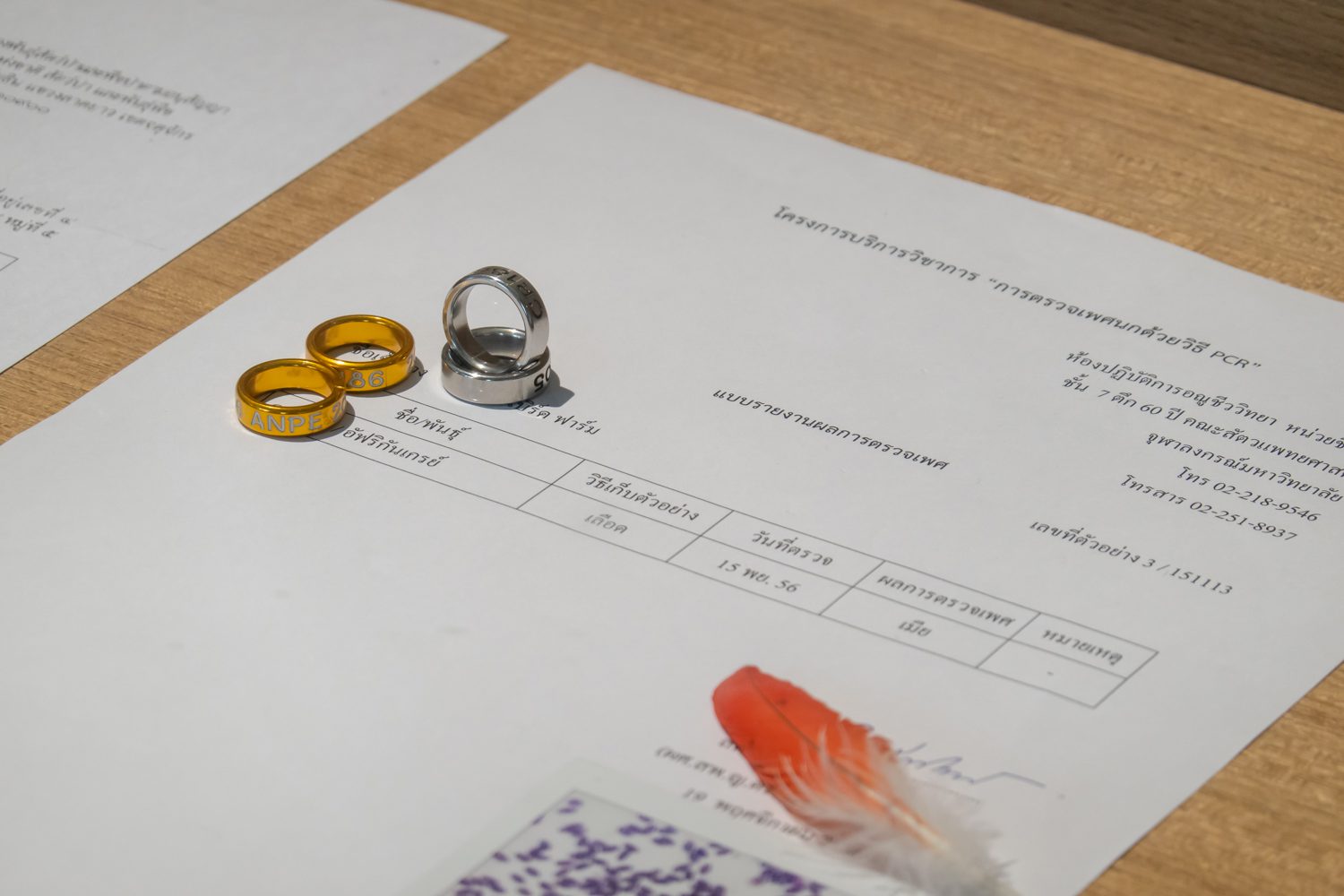

In the closing section of the exhibition Beuys’ Archive (2025), Wantanee turns her attention to the objects collected in relation to the African Grey parrot she raised, from bird food packets to veterinary receipts, and leg bands. There are also feathers, some of which are carefully arranged in size order on the table, covered with a clear acrylic case, while others are loosely gathered in a display cabinet. In one sense, these artifacts offer viewers a closer look at the bird. But at the same time, they cannot fully define or contain it. They are simply traces, remnants that have fallen away from the body and were gathered along the way. These fragments undeniably point back to the parrot. Yet each object also asserts its own autonomy, separable from the original body and capable of erasing its source while continuing to exist in its own right.

Remnants of Fading Shadows draws attention to the distance between us and what we perceive; how limited our capacity for contact truly is. Within the historical landscape we inhabit, what we see, confront, and collide with may not represent the whole of what ‘is.’ And there may be no way to collect it in its entirety. Part of it may exist just beyond the edge, just out of reach. Another may overflow the frame entirely, slipping into the distance. What remains is a need to recognize the limits, the fractures, and the inherent incompleteness of it all. What we perceive, see, and hold onto may be nothing more than mere remnants of shadows, destined to fade.

This thinking on surface does not refer solely to the physical skin of objects on view.

It also extends to the projection screen, and to the retina of the viewer’s eye.

The exhibition Remnants of Fading Shadows by Wantanee Siripattananuntakul is on view from June 19 to August 31, 2025, at the Silpakorn University Art Centre (Wang Tha Phra).

_

1 In this video, the elephant depicted is an ordinary elephant altered to appear as an albino due to legal restrictions. For further details, see: Panu Boonpipattanapong. (2025, July 6). “Remnants of Fading Shadows: Weaving Together Political Themes and the Faint Traces of Personal Memory.” Matichon Weekly. https://www.matichon.co.th/weekly/column/article_849152

art-centre.su.ac.th

facebook.com/ArtCentre.SilpakornUniversity