READING THE SEISMIC EDGES OF NATION-STATES THROUGH THE EXHIBITION UNDO PLANET PART 1: UNDO DMZ

TEXT: KANDECH DEELEE

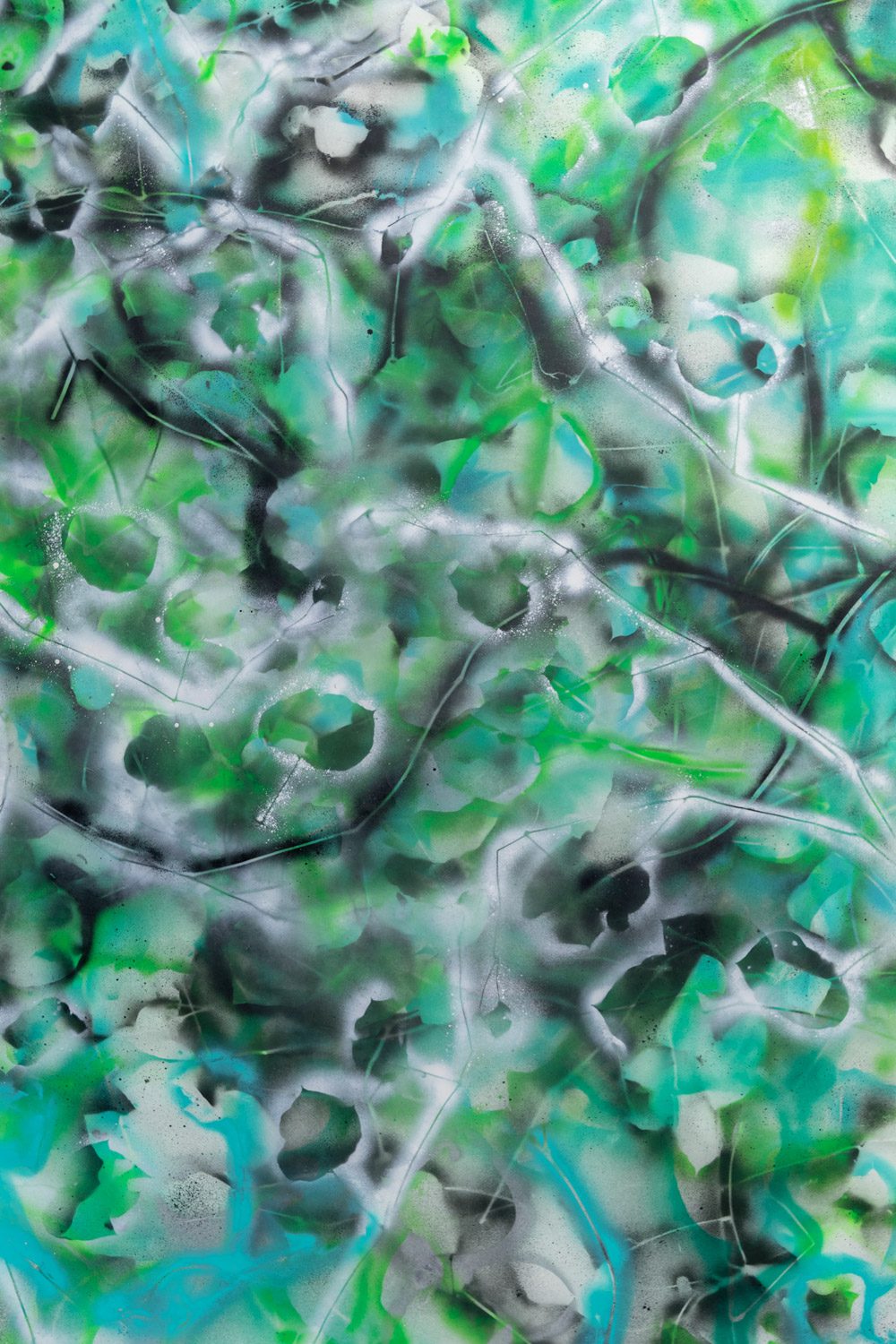

PHOTO COURTESY OF BACC

(For Thai, press here)

Tectonic plates of nation-states press and grind against one another, setting off tremors that seem to push the edges of the earth outward. A new terrain rises in the space between invisible fault lines, strange yet familiar, like a primordial genesis whose destination is visible even as the path toward it remains absent. In one sense, it is a buffer state forbidden to any form of possession; in another, it feels as though its former occupants are circling back to reclaim what they once held. At the heart of this emergence lies a crucial question: is this an advance or a retreat?

The familiar refrain that ‘borders are an invention’ is often invoked when violence erupts between states along contested frontiers. Yet it is just as often that this supposed invention hardens into something palpably real, a line that can be touched, measured, and enforced. Such is the case with the Korean border. When the Korean War ended in 1953, the Korean Armistice Agreement established the Korean Demilitarized Zone, a two-kilometer-deep buffer carved on each side of the border and extending for 250 kilometers across the peninsula. As human access to this zone was restricted for decades, its landscape and topography began to transform, as though reclaimed by nature itself. Rare species of flora and fauna have been discovered living and thriving within this forbidden stretch of land.1 This phenomenon became one of the central fascinations of the exhibition ‘Undo Planet Part 1: Undo DMZ.’

Although the Demilitarized Zone was once a site of extreme violence, the exhibition itself reveals no signs of bullet holes nor the smell of soot, neither remnants of weaponry nor the contextual framing that so often feeds the archive of assumptions carried in by those on the verge of becoming viewers. Instead, the exhibition reveals war’s remains so thoroughly altered that they are nearly unrecognizable. What should have been familiar visual markers have been erased by time. The body of war survives only as fragments of landscape, elements that can be shifted, displaced, or effaced until their origins dissolve completely. Birds, mountains, grasses, and the murmur of the forest become both here and there, unsettling the certainty that the ‘forms’ we think we ‘remember’ are truly the ones that were. In White Cranes and Snowfall (2024) by Young In Hong, the footprints of cranes pressing into the snow gather into imprint after imprint, marking and sealing, invoking and forgetting, all in the same moment.

In another register, several works turn their attention toward the act of archiving the terrain itself. In Trace (2023), Andrian Göllner documents the many species of birds inhabiting the Demilitarized Zone through delicate watercolor paintings. Meanwhile, DMZ Botanic Garden (2019–present) by Kyung Jin Zoh and Cho Hye Ryeong gathers twenty-three selected plant species as representatives of the flora that has flourished within the zone. The accompanying texts for both works underscore an effort to understand and record a landscape whose ecosystem has changed in the absence of human presence. Here, recording becomes a means of imposing a kind of order upon what might otherwise appear disorderly, (or, perhaps of revealing an order that already exists, simply awaiting discovery). Through these systems of classification, the ambiguities of life within the Demilitarized Zone become newly legible, linked to the outside world through registers that establish continuity rather than rupture. Collectively, these works highlight the significance of the environment, the traces of human impact, and the conditions that emerge when humans are removed from the equation. The DMZ becomes a site of possibility, a reference point for evidence of ecological transformation in a world briefly freed from human intervention. It also prompts questions about the complex relations between humans and the nonhuman forms of life.

Another group of works discusses the interactions between humans and the DMZ landscape. In Dreaming Birds Know No Borders (2021), Jin-me Yoon films at the mouth of the river along the 38th parallel, capturing a young man moving in the gestures of a crane. His movements are intercut with footage from a North Korean film made in the 1990s about an ornithologist separated from his family after the establishment of the DMZ. The video also plays with the original soundtrack of the film, which is run in reverse and set against the life of the ornithologist who can never return. The work thus offers more than a direct depiction of borders or the DMZ. It engages in acts of substitution, distortion, and inversion. The young man’s raised, pinched fingers echo and interrupt the shots of a crane’s head. Images of crane families are interwoven with scenes of the ornithologist who has been rendered kinless. One might say that an invisible wall begins to form before any physical border becomes visible, before the shape of the land shifts in accordance with an imagined demarcation. All of these crossings, reversals, and overlaps challenge the territory of a border that is at once constructed and real.

Meanwhile, another work, Mixed Signals (2025) by Joon Kim, slices the Demilitarized Zone into fragments as a way to approach a place that cannot be entered. Kim arranges photographs of various viewpoints within the DMZ inside wooden boxes fitted with speakers that play sounds recorded on-site. These boxes, suspended and set in motion, sway back and forth until they produce a resonance that fills the space. What is striking is that neither the photographs nor the recorded sounds allow viewers to distinguish, recognize, or pinpoint any specific features of the Korean DMZ. Yet it is precisely this inability to differentiate that reveals how the DMZ might be understood as an ’any-space-whatever’ : a space stripped of geographical specificity and functional clarity, but one that brings our attention back to ‘space’ as space in its own right. Multiple forms of possibility collide and coexist within it, unfolding simultaneously.

It is striking that a formless ideology can nonetheless possess the power to reshape terrain. The imagined border dividing the two states has come to resemble two tectonic plates colliding, grinding, and pressing against one another, generating tremors whose impact radiates far beyond the point of contact. When the clash between these imagined crusts subsides, the space between them opens into a kind of vacuum, a gap created by the outward force of expanding power. Although decades have passed, the tension between North and South Korea continues to smolder beneath the surface. The Demilitarized Zone thus exists at once as a buffer state and as an active fault, one that may at any moment shift, crack, or tremble into renewed movement.

The introductory panel at the entrance reads: ‘Undo Planet may be understood both as ‘returning the world to its original state’ and ‘unsealing a world once shut off.’’ This presents the DMZ through an environmental lens, as a terrain where the deep-time forces of the ancient world seem to have reasserted themselves. It is a place that once belonged to an earlier order, a present-day forbidden zone, and perhaps a future landscape devoid of humans. Yet even so, the Korean Demilitarized Zone came into being through human-made violence. It is the result of a deliberate act of ‘invention’ rather than a naturally occurring phenomenon arising without intention or timeline. And the distant past of this landscape was never identical to what we see today.

In one sense, the DMZ reveals a process akin to the healing of wounded flesh: an inflamed lesion that gradually recovers, hardens into a scab, and eventually peels away to resemble what it once was. But this is only a ‘condition,’ a state produced by the body after an intervention, a transformation driven by forces inside and out, entwining the organic and the imposed. The emergence of this new terrain, this new flesh, is therefore something genuinely new. It is not simply the unearthing of what had long been suppressed, for the distant past possessed its own ‘time.’ Any return to antiquity must still contend with temporal boundaries, markers that inevitably reach an end. The DMZ, then, remains inseparable from the very processes through which humans have intervened. Something has shifted here, in ways both perceptible and beyond recall. Certain residues may still persist, concealed yet quietly exerting their influence, never truly gone. This Edenic garden is thus an inheritance of violence, a remnant of loss, and a fragment of the goddess of war.

Undo Planet Part 1: Undo DMZ is on view at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, 7th floor, from 25 October to 25 November 2025.

_

1 Healy, H. (2007). Korean demilitarized zone: Peace and nature park. International Journal on World Peace, 24(4), 61–83.