MARTIN CONSTABLE PRESENTS IMAGES OF EMPTY SPACES THAT HAVE BECOME THE LANGUAGE OF HIS MEMORIES AND PERSONAL HISTORY THROUGH ‘WHAT CANNOT BE FORGOTTEN, MUST BE CELEBRATED’

TEXT: TUNYAPORN HONGTONG

IMAGE COURTESY BANGKOK UNIVERSITY GALLERY AND THE ARTIST EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

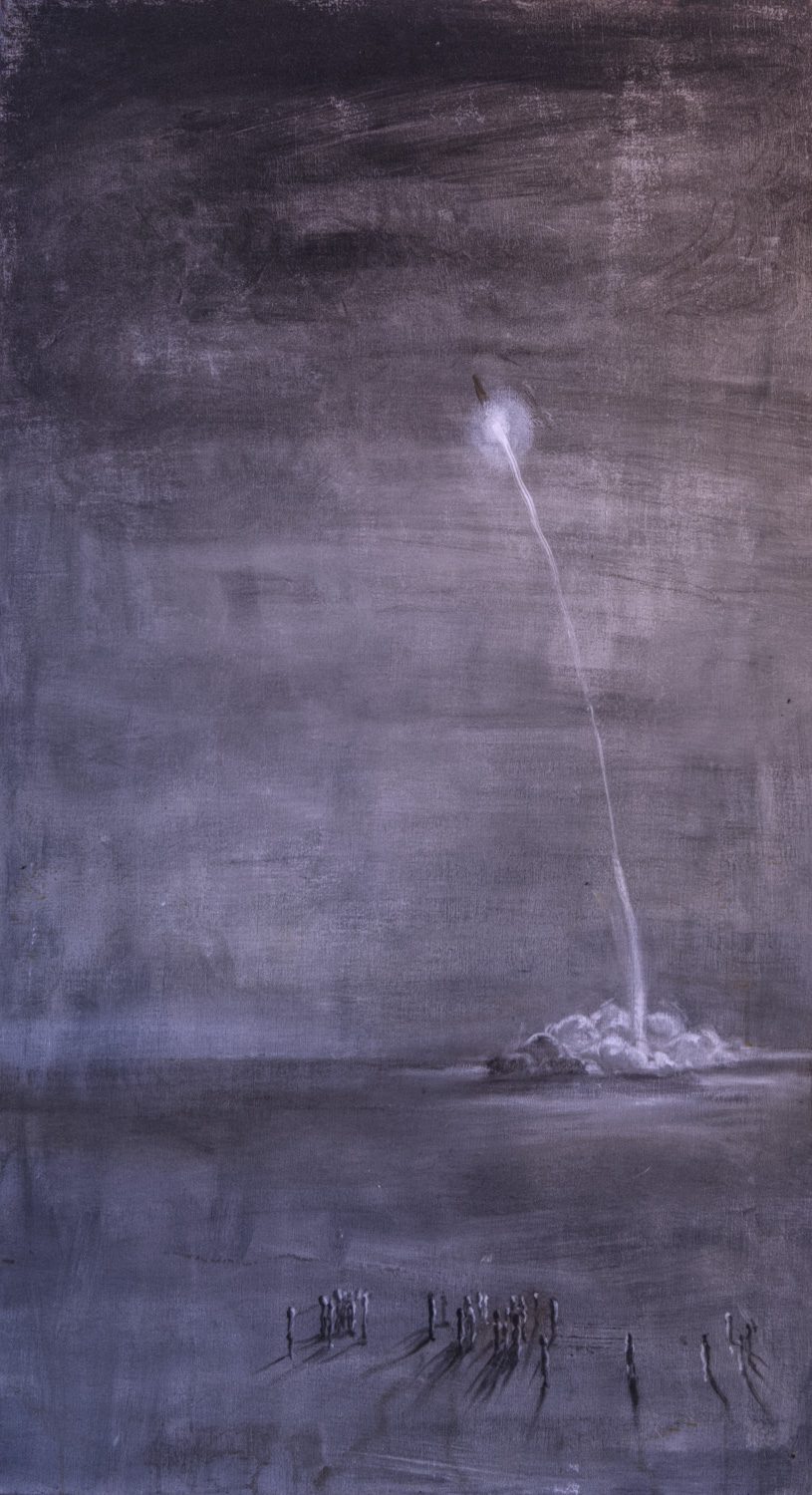

In Martin Constable’s oil paintings, the world exists in shades of white, black, and gray. The scenes are desolate, their structures worn and decaying, as if time itself has seeped into every crack and fragment. Human presence is almost entirely absent, if it appears at all, it is reduced to faint, anonymous figures, small and insignificant.

His digital prints present a similar world. While they introduce a touch more color and a semblance of civilization such as a laboratory, an art museum, an artist’s studio, a home, a craftsman’s workspace, these spaces remain eerily vacant. The only traces of humanity lie scattered among the objects that fill them, remnants of use rather than signs of life. Even here, Constable’s compositions remain completely devoid of living beings.

Photo: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai, courtesy Bangkok University Gallery and the artist

This absence of humanity in ‘What Cannot Be Forgotten, Must Be Celebrated’ becomes the viewer’s first provocation; an invitation to question and reflect.

In an interview between Martin Constable and Pojai Akratanakul, the curator of the exhibition, the artist was asked about the disappearance of human presence in his digital print series ‘The God of Details’ (2025). Constable did not offer a direct answer. Instead, he traced the origins of the series, explaining that it began simply as an attempt to depict a range of different environments. In the process, however, he came to realize that these images were, in fact, his own autobiography. The spaces he created, whether the laboratory, his father’s workshop, or the art museums he visited as a student, were fragments of his personal history. ‘It often happens this way,’ he reflected. ‘We begin working, and only with time do we discover how deeply the work connects to our own stories.’

Even if the artist refrained from addressing the absence of people directly, Pojai offers her own reading in the exhibition essay. She suggests that the vacant rooms, studios, and workspaces in ‘The God of Details’ might operate in the same way as a computer screensaver, as a momentary pause. Perhaps the reason his digital prints are devoid of people is that those who once occupied these places have momentarily stepped away and may soon return, just as a screensaver vanishes the instant one touches a key to resume work.

Yet viewers may experience something altogether different. Beneath the pristine precision and dramatic interplay of light and shadow, these images often carry a haunting stillness. One might begin to wonder whether this is truly a pause before renewal, or the end of humankind itself, as if something has gently erased every trace of human life from the world.

Ambiguity is another defining quality of Constable’s art, particularly the ambiguity that hovers between two moments in time. Not only are we uncertain whether ‘The God of Details’ marks an intermission or an ending, but many of his oil paintings seem suspended between past and future. Works such as ‘Lustrum’ (2024), featuring a small crowd watching a shuttle launch; ‘Rebes Minor’ (2021), which depicts the ruins of a medieval castle; and ‘What He Left Behind’ (2025), showing a barren, lunar-like landscape, leave us to wonder whether these images portray a bygone world or a past about to return.

One thing we can be certain of is that many works in this exhibition touch upon the realm of historical memory. Among them, ‘What He Left Behind’ revisits one of the most iconic images in human history: ‘Earthrise’ (1968) by William Anders, the astronaut who captured it during the Apollo 8 mission to the moon. The photograph shows Earth rising above the lunar horizon, a blue sphere adrift in the dark expanse of space. In one corner, the rough, cratered surface of the moon reveals that the image was taken from Anders’s vantage point as he looked back toward Earth while orbiting the moon. ‘Earthrise’ came to represent the triumph of human endeavor. It was the moment humankind reached beyond its home to explore the cosmos. Yet, at the same time, it offered a humbling perspective: that our world, our small blue planet, is merely one fragile celestial body within the vast universe.

Constable isolates what once appeared only at the edge of that photograph; the moon’s rocky, deserted surface, and transforms it into the central subject of his painting. By doing so, ‘What He Left Behind’ transforms the site of humanity’s great achievement into one of emptiness and abandonment, without any form of life, even of those who once set foot there.

In truth, Constable’s underlying idea seems to echo William Anders’s famous reflection: ‘We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.’ Seeing our planet from the lunar surface made humanity acutely aware of its own smallness. In ‘What He Left Behind,’ Constable appears to turn that realization into a quiet question: What remains of our triumph now? Even those who once traveled farther than anyone before no longer exist, for Anders himself passed away in 2024, a year before Constable painted this work.

Photo: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai, courtesy Bangkok University Gallery and the artist

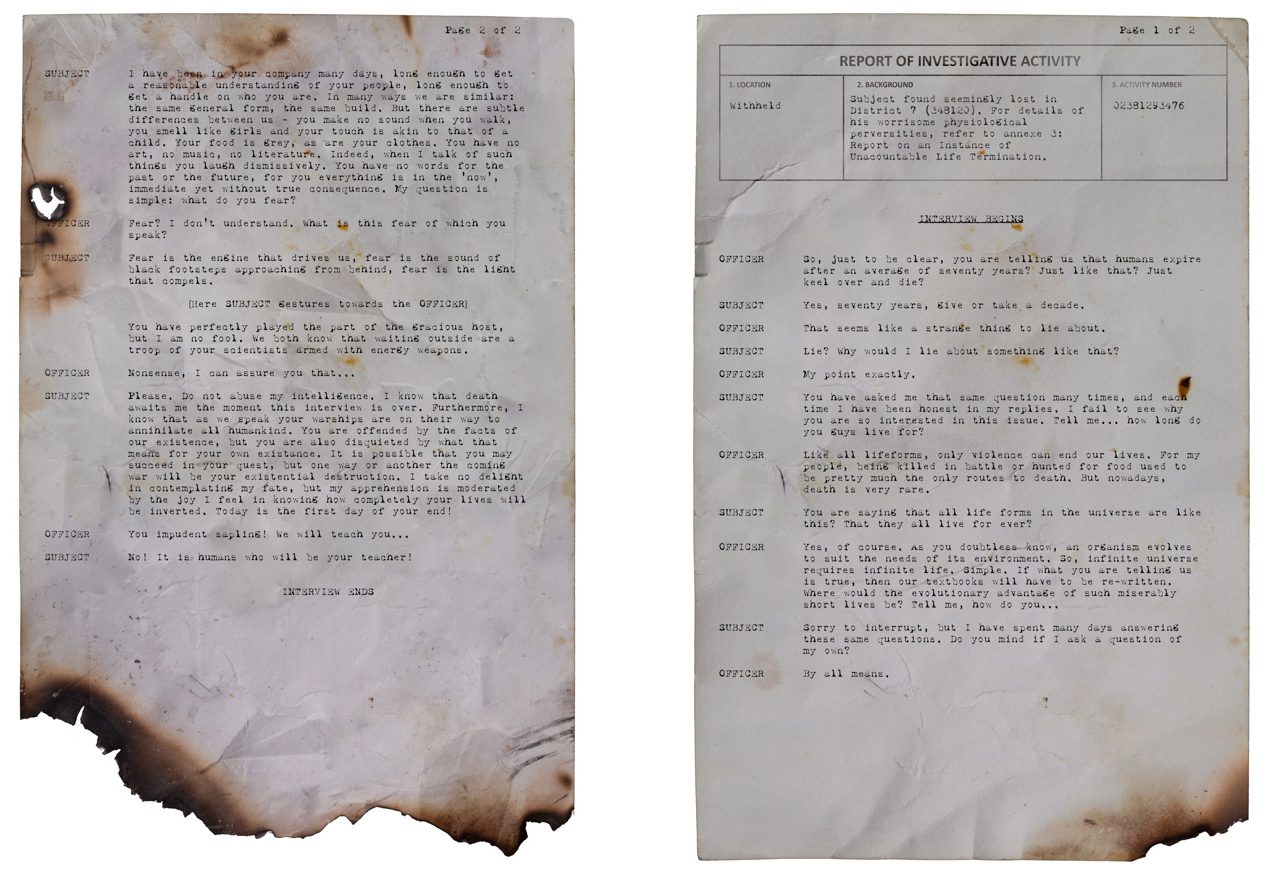

Beyond Apollo 8, the story of Apollo 11, the first mission to land humans on the moon, also finds its way into Constable’s work. In ‘Fragment From an Interrogation’ (2025), the artist reimagines a document based on the contingency speech prepared for President Richard Nixon in 1969, intended to be delivered had the Apollo 11 mission failed. In Constable’s version, however, the text becomes a transcript of an interrogation between an unnamed officer and an unidentified individual. Their dialogue revolves around a single theme—‘the expiration of life.’

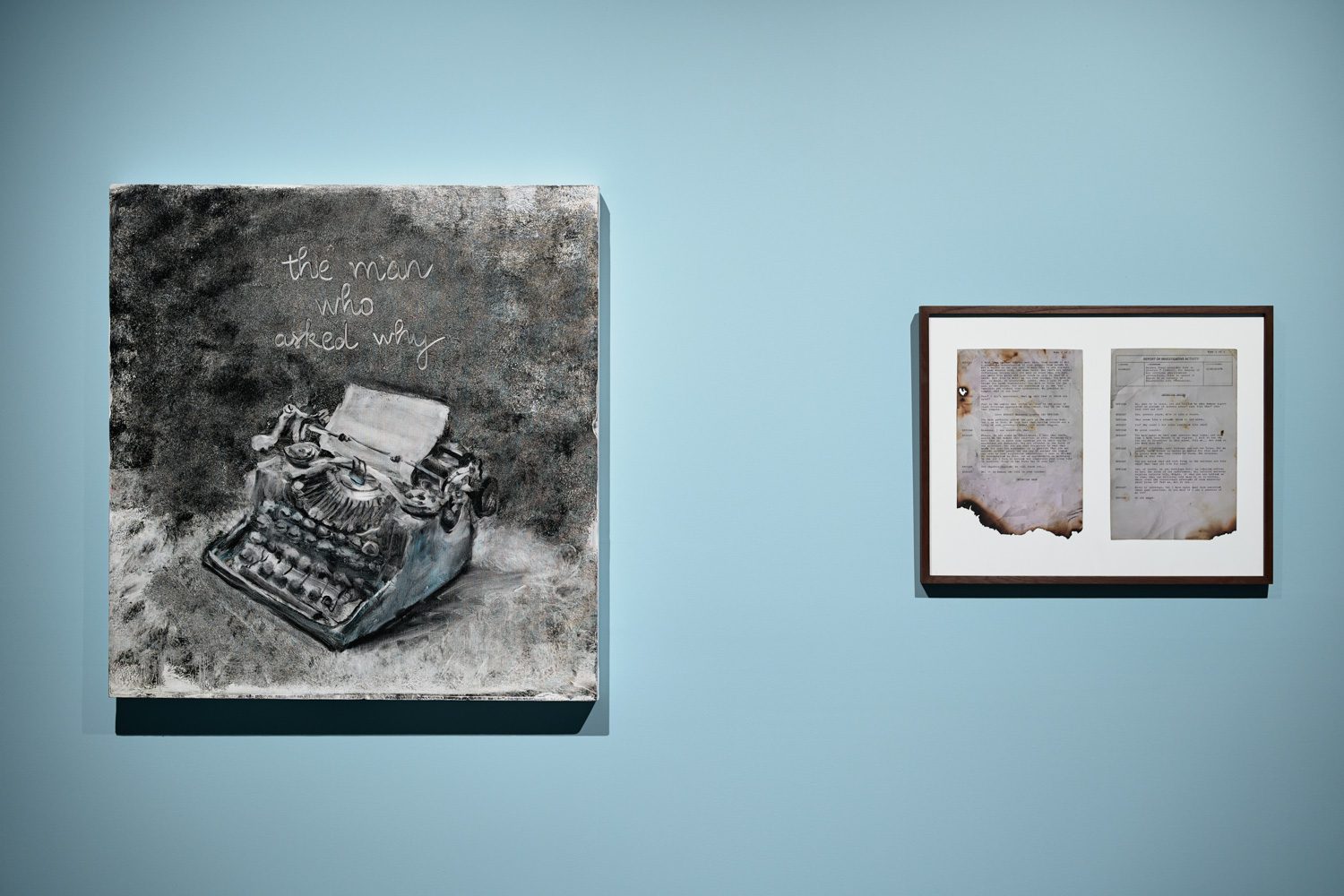

The anonymity of the figure under interrogation in ‘Fragment From an Interrogation’ mirrors the absence of human presence in ‘The God of Details.’ The same sense of vacancy pervades ‘The Man Who Asked Why’ (2025) and ‘In League With His Demons’ (2024), which depict, respectively, a solitary typewriter and an artist’s studio filled with tools and materials awaiting use. Yet the makers, their owners, are nowhere to be found. In other words, Constable’s images are filled with the instruments of creation but bereft of the ‘creators’ themselves.

Photo: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai, courtesy Bangkok University Gallery and the artist

This idea becomes even more pronounced in ‘Half Way There is Half Way Gone’ (2025), a painting of a pair of boots. The image recalls Vincent van Gogh’s ‘A Pair of Shoes’ (1886), a work long at the center of one of the most famous debates in art philosophy. As Pojai notes in her essay, Martin Heidegger interpreted van Gogh’s shoes as revealing the world of the peasant who wore them, while Meyer Schapiro rejected that view as presumptuous. Jacques Derrida later added that no one could ever know whose shoes they truly were, and that all interpretation inevitably arises after the disappearance of the owner.

The philosophical dialogue hidden within these two works compels us to reconsider Constable’s entire body of work. Seen through this lens, his paintings and digital prints may not be as ‘desolate’ or ‘empty’ as they first appear. As Heidegger once wrote, ‘Unconcealment is the revelation of being.’

‘What Cannot Be Forgotten, Must Be Celebrated’ can thus be read as an invitation for viewers to look into these seemingly uninhabited spaces and, in doing so, turn their gaze inward. Rather than observing the lives of others, we are prompted to confront our own memories and our own state of being; to recognize traces of existence in images where no one remains.

‘What Cannot Be Forgotten, Must Be Celebrated’ by Martin Constable, curated by Pojai Akratanakul, is on view at Bangkok University Gallery (BUG) from October 14 to November 29, 2025.

Photo: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai, courtesy Bangkok University Gallery and the artist

Photo: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai, courtesy Bangkok University Gallery and the artist