IN THE MIDDLE OF THE HIGHLY URBANIZED SINGAPORE, AKHA ARTIST BUSUI AJAW AND VANGHOUA ANTHONY VUE, A BRISBANE-BASED MONG-LAOTIAN ARTIST, COINCIDENTALLY RECREATED THE VILLAGES WHERE THEY WERE BORN AND BRED. SHOWCASED AT THE SINGAPORE BIENNALE 2019

TEXT: BONGKOCHAKRON KAMPUK

PHOTO: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

In the middle of the highly urbanized Singapore, Akha artist Busui Ajaw and Vanghoua Anthony Vue, a Brisbane-based Mong-Laotian artist, coincidentally recreated the villages where they were born and bred. Showcased at the Singapore Biennale 2019 (themed ‘Every Step in the Right Direction’) inside Gillman Barracks, the two installations implicate artistic expressions that reference the artists’ marginalized ethnicities and their labeled ‘minority’ status.

Presented into two parts, the first part of Ayaw Jaw Bah (2019) by Busui Ajaw consists of a number of paintings telling stories about the origin of Akha, the relationships between its people, ghosts and nature, the legend of Ayaw Jaw Bah, the despised King of Akha’s tribe whose chaotic reign had caused his descendants to flee to the west and never return. The second part is an installation which reimagined the village’s entrance adorned with sculptures of the tribe’s guardian. The symbol, which can be found in every Akha village, represents the door that separates the earth and the spiritual world, and holds the power that prevents and protects villages from evil.

While the use of paintings and sculptures with the storytelling looks and feels a bit too straightforward, no one can deny the fact that the artist’s experience growing up in a Shaman family creates this raw, natural reality through figures of naked human bodies with their genitalia fully exposed.

‘Is it too exotic?’ The question arises when the rawness of tribal culture becomes the center of the work’s story. It doesn’t discuss or uncover any issues happening in the artist’s homeland. Superficially, the earlier explanation feels right but is this what the work really about?

With the Akha not having a written language, their stories were verbally passed on through time. The work, according to the artist’s explanation, is the tool she uses to document the way of life, history and legends of her people. At the same time, it attempts to discuss the connection between Westerners and the propagation of Christianity that ended up converting many Akha people as old beliefs and rituals were gradually replaced.

Busui Ajaw’s artistic documentation is an implication of her fear about the disappearing beliefs and identity. Christianity symbolizes the people’s adaptation as they left behind old beliefs that no longer resonate with life in the modern world. The old way of life that closely associates itself to nature and spirits dissipates as the ‘new’ is swallowing up the root of their beliefs. The issue is like a rerun of the movie where Siam elites struggled through the 19th century as their attempt to imitate the West-defined civilization was done through the categorization of people, consequentially marginalizing those who didn’t make the cut as ‘uncivilized jungle people,’ Strangely, the similar scenario is now being repeated.

The state’s development of the Akha community first took place between 1982 and 1990. Driven by the same conviction of bringing civilization to those who are less civilized, the Thai government’s actions were, however, different from the Western colonizers in the sense that the Akha were not classified as jungle people but as citizens whose connection with Thailand was defined by the state-granted nationality and state-guided way of life through economic agriculture, education and access to public utilities.

Instead of originating from the Akha’s actual desires for this so-called civilization, these imposed developments came with Thai government’s agenda of using Akha villages as the defense line to prevent minorities from joining the Communist camp during the Cold War. What seemed to be an improvement in the quality of life that was self-generated was followed by the imbalance of the new way of life that was happening in the same geographical area. The society of the tribal people began to fall apart.

Connections between families disappeared as young people moved to the city. The new values made the Akha view their old way of life as uncivilized and underdeveloped. What’s sadder was that even these people wished to become a part of the modern society, they couldn’t. Without nationality, they will continue to be treated unequally, stuck in the middle between the old life in the mountain and the new life in the city. To survive, they took the last option of turning themselves and their homes into a form of entertainment. Villages get turned into tourist attractions for people in the city who get a kick out of curated nature and the exotic tribal people.

Busui Ajaw wasn’t just telling the story of her people, and it isn’t entirely true that her work doesn’t provoke an impact. The truth of the matter is, the problems are hidden underneath what’s seemingly ordinary. It isn’t any different from the way people nonchalantly treat minorities like they’re mascots. But Ajaw’s isn’t the only work about minorities that the Singapore Biennale gets to welcome. Not too far, across the hall, is Vanghoua Anthony Vue’s installation.

Photo courtesy of Vanghoua Anthony Vue

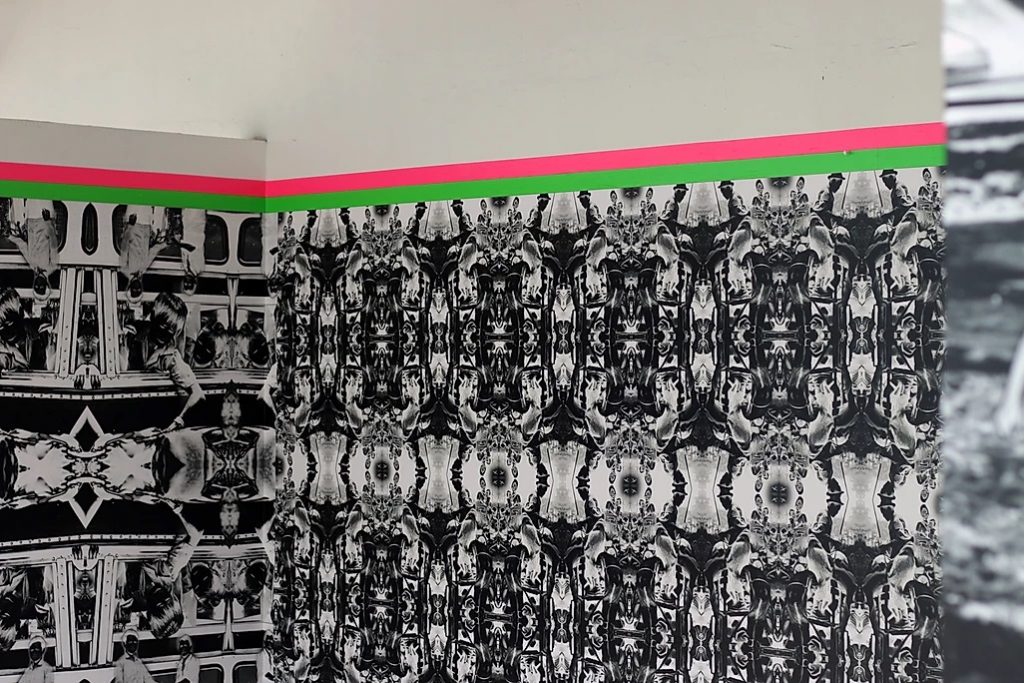

While also addressing minority people’s issues, Vue’s work differs from Ajaw’s. It doesn’t focus on nature, spirituality or rawness. Instead of letting the viewers think about the problems by themselves, it guides us directly straight to the point as Vue openly discusses the problems. In ‘Present-past-patterns’ (2019), the Mong-Laotian artist attached, with fluorescent vinyl and duct tapes, photographic prints onto the building’s exteriors, reflecting the Mong’s clothing patterns.

This work was created to reflect the Mong’s struggles, similar to the Akha’s, as they’ve become marginalized and stateless people, forgotten by history. He used his family’s story: his parents had lived in Laos until the civil war when the Mong fought against, and lost to, the Communists. They ran away to Thailand, having barely survived the war, but life then was not easy. After more struggles, they finally managed to settle safely in Australia.

Photo courtesy of Vanghoua Anthony Vue

Despite the Mong’s role in and impact from the so-called Secret War, their heroic deeds and struggles have never been recognized by the Lao history. This inspired Vue to present his family photos and those of the Mong’s fights during that tumultuous time to the public so that we realize and recollect the actual incidents.

Looking at this work from a distance, viewers didn’t see photographs and tapes, but Mong’s clothing patterns installed on high mounds resembling pavilions. These patterns were created by the juxtaposition of the artist’s family photos taken in a Thailand’s refugee camp and those in the war. The artist’s implication here is that he wanted the viewers to see, more clearly, the identity of the Mong as well as their ancient knowledge, all reflecting their ways of life, culture and traditions.

Photo courtesy of Vanghoua Anthony Vue

Also noteworthy is the fact that the photographic prints were installed along the walkways between Gillman Barracks’ buildings. Not many passers-by would take a closer look at the details; in other words, they may have “seen” it but didn’t actually “looked at” or become interested in them. This is like how the Mong history has never been documented in the Lao history. Like many other minority people elsewhere, the Mong have been facing repeated patterns. On the contrary, those biennale visitors who cared to stop and look closely at this installation would get the messages, passed on to us here and now, like the Mong clothing patterns being inherited by one generation and the next.

Ajaw’s and Vue’s works are comparable: they’re both based on the artists’ need for their stories to be recognized and documented. This results from the fact that the minority people have been rejected and marginalized for a long time. Having been overlooked and unrecognized, they want to reclaim the minority people’s existence, memory, importance and equal treatment in their respective societies. Moreover, both artists’s works are related to the Cold War. Although the Akha weren’t expelled and had to run for their life like the Mong, the former’s unique ways of living and identity have slowly been fading from the public eyes, similarly to how the Mong villages were demolished in the fire of war.

Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

The Singapore Biennale 2019, from November 22, 2019 to March 22, 2020, is hence an important step for minority arts. Finally, these people are given proper opportunities to create works to explain themselves through their points of view, rather than being defined or marginalized by others.