AN EXHIBITION THAT BRINGS TO LIGHT THE UNSEEN PROCESS OF THE GALLERY, AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN UNEXHIBITED ARTWORKS, STAFF ACTIVITIES, AND VISITORS

TEXT: WICHIT HORYINGSAWAD

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

If we were to compare WAREHOUSE to the standard definition of an art exhibition, there would probably be quite a dissimilarity.

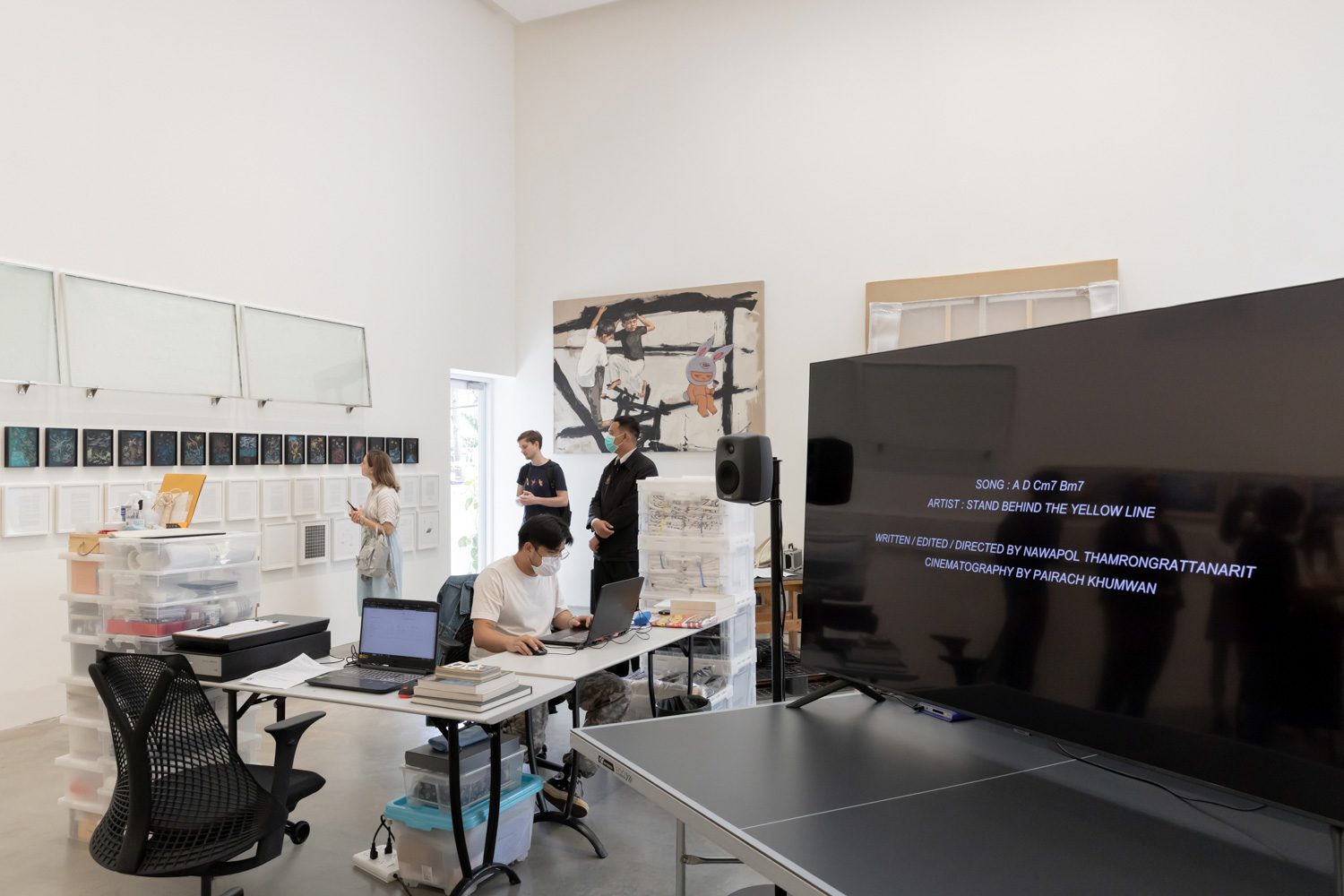

By taking a look around the exhibition space of BANGKOK CITY CITY GALLERY, one can see items and objects scattered all over the place in a quantity that exceeds that of most art exhibitions. Nevertheless, some of the displayed objects look familiar, like art works that I saw in other shows prior to this. They were securely packed in boxes; some were wrapped in unusual shapes in ways that most people would not expect to see art objects being displayed. Some look like used podiums or stands of some sort, while others appear to be some kind of banners or graphic design pieces from old exhibitions which were folded and stored.

The lighting in the gallery illuminates the entire space in the manner of a trade fair or exhibition, with no single product or space being particularly localized or emphasized. The staff’s working desk is in an easily noticeable location, serving as a reception area for visitors. Kankawee Trichit, the gallery assistant, was busy working on a site map that offers primary information about the exhibited art works at the time of my visit. Kankawee was collaborating with Chollaphat Nuchthongmuang, who oversees the inventory and manages the day-to-day logistics of the gallery’s artworks coming in and out. The collected data was then sent to the graphic team to be digested into a simple infographic for viewers in the following days.

Heading further inside, the large doors on the side that connect the exhibition area and the office are opened, allowing people to stroll in and observe the room where more artworks are kept. The section is usually exclusively accessible to gallery personnel and is not open to the public. By making the two spaces available for public viewing, the exhibition space looks and feels even more distinct from shows previously held within the gallery.

The curator, Nawin Nuthong, discussed the placement of the displayed artworks while personally giving me a tour of the show. He began the process with a sketch that he thought would complement the selected artwork. Nevertheless, as the development process advanced, he learned that what he had in mind wasn’t quite the answer he was looking for because these items function under different conditions that vary from day to day. He wasn’t aware of the actual number of pieces that will be shown, and as the inventory grows, additional objects emerge. Along the way, he discovered that some of the works were not even listed. These circumstances hinder him from seeing the big picture, but they also allow him to see the relationship between the exhibited objects and the viewers. These connections help to clarify the artist’s artistic and conceptual development, as the exhibition’s significance lies in the relationships between the displayed objects and artworks. Perhaps what WAREHOUSE intends to depict is the labor behind the flow of activities driven by both individuals and displayed objects, which would normally exist as a part of the behind-the-scenes process of an art exhibition.

If one were to view the exhibition activities from Chollaphat’s standpoint as the inventory specialist whose job it is to handle the full flow of all the art works being brought in and out of the gallery, one would realize that he holds a wide range of responsibilities. They encompass the purchasing and inventory inspections, as well as the documentation of art pieces, including loaned and returned ones. Chollaphat is required to work with both people and objects because his responsibilities include the management of artworks. His works are related to back-of-house operations, tracking each work back to the people and things that result in its existence, as well as keeping track of each art piece’s information. Each work’s information will be regularly updated. All of these activities are what the gallery staff typically do at the beginning of the year—a sort of yearly major review—but only this time they allow the public to learn about the entire process in the form of an exhibition.

During the tour, Nunnaree Panichkul, the gallery manager, shared her perspective. “When we discuss the nature of a warehouse, there is this palpable aspect of something concrete, ready to be transferred to new destinations. But we also don’t think of these artifacts waiting to be relocated only as physical things like sculptures or paintings, but as the sum of what viewers might experience and learn from them. It’s as if we’re storing some sort of knowledge in this warehouse, waiting for the viewers to bring it back with them, and vice versa, because the viewers also offer something to our experiences that could also be useful for future work.”

Kankawee, the gallery assistant, noted the rare chance of viewers witnessing the flow of the gallery’s activities during our conversation about the workflow of the complete work process. He gestured to the laptop and held his smartphone before describing how certain tasks are completed via email and text messaging rather than in a traditional physical space. As a result, the exhibition only showed parts of the entire process. Visitors to the exhibition will undoubtedly notice activities taking place as part of the workflow, as well as the various ways artworks are kept and displayed throughout the duration of the exhibition. The staff would continue their regular roles, each with their own daily responsibilities, and spectators are welcome to ask questions and speak with gallery personnel as well as other exhibition goers if they wish.

WAREHOUSE is now showing at BANGKOK CITY CITY GALLERY from February 8th to February 25th, 2023.