PICTURING MODERNITY, A PHOTO EXHIBITION THAT OFFERS NEW PERSPECTIVES ON BANGKOK’S MODERN ARCHITECTURE BY THREE PHOTOGRAPHERS: WEERAPON SINGNOI, WALTER KODITEK, AND RABIL BUNNAG

TEXT: CHOMCHON FUSINPAIBOON

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

Among those with a keen interest in modern architecture, particularly structures built between the 1950s and 1970s, the names Weerapon Singnoi and Walter Koditek are likely familiar. Both are architectural photographers known for their extensive documentation of modernist buildings in Bangkok and across provincial Thailand. Their images, captured over many years, have been consistently shared through their personal social media platforms. The name Rabil Bunnag, a master photographer of an earlier generation, may be more readily recognized among history enthusiasts and scholars. His photographic archive, housed at the National Archives of Thailand, comprises approximately 23,000 images, of which only a selected portion primarily focused on historical sites has been made publicly accessible. Yet few are aware that within this vast collection lies a lesser-known but equally compelling body of work: photographs that document the emergence of modern architecture and the evolving urban landscape of Bangkok in the 1950s.

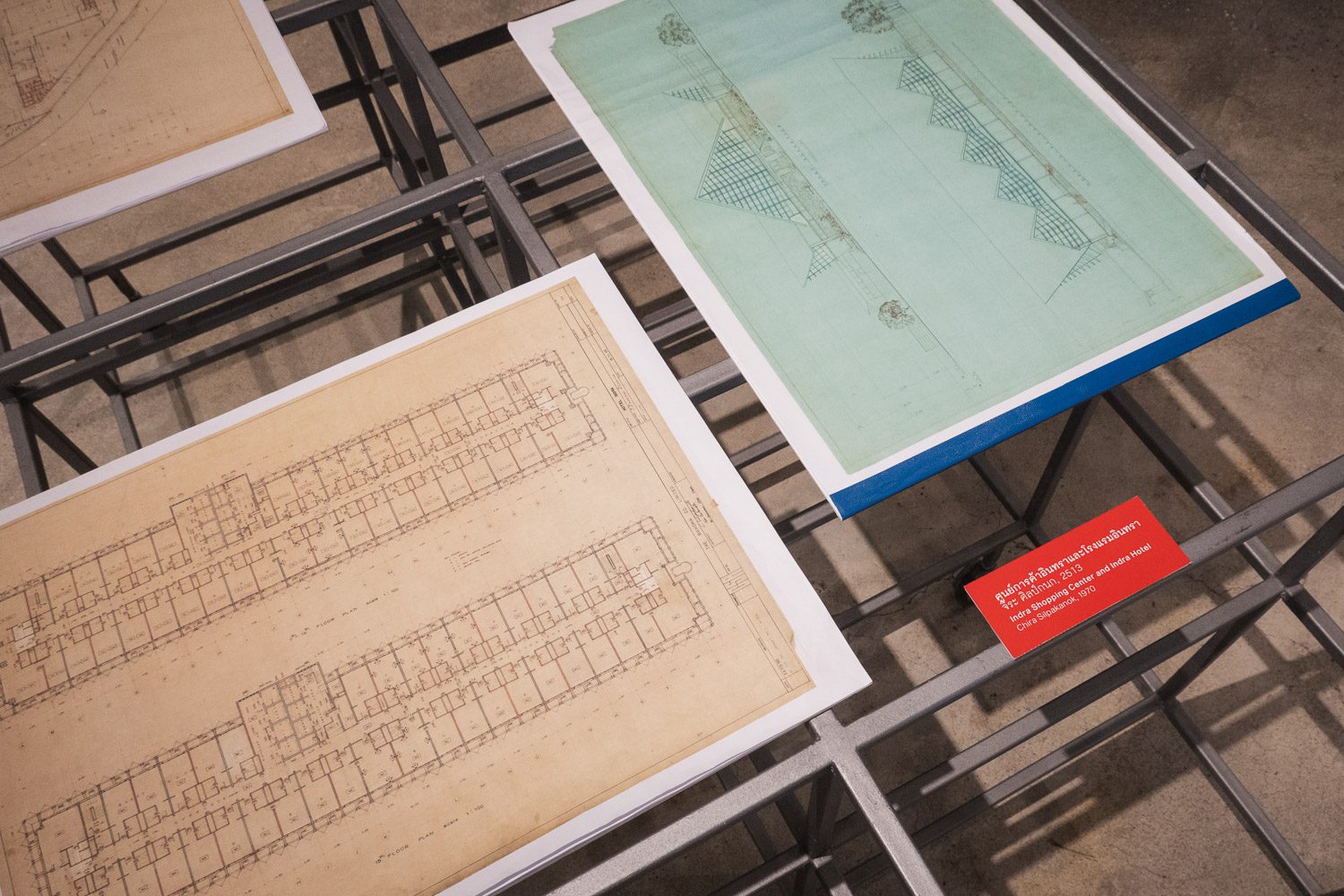

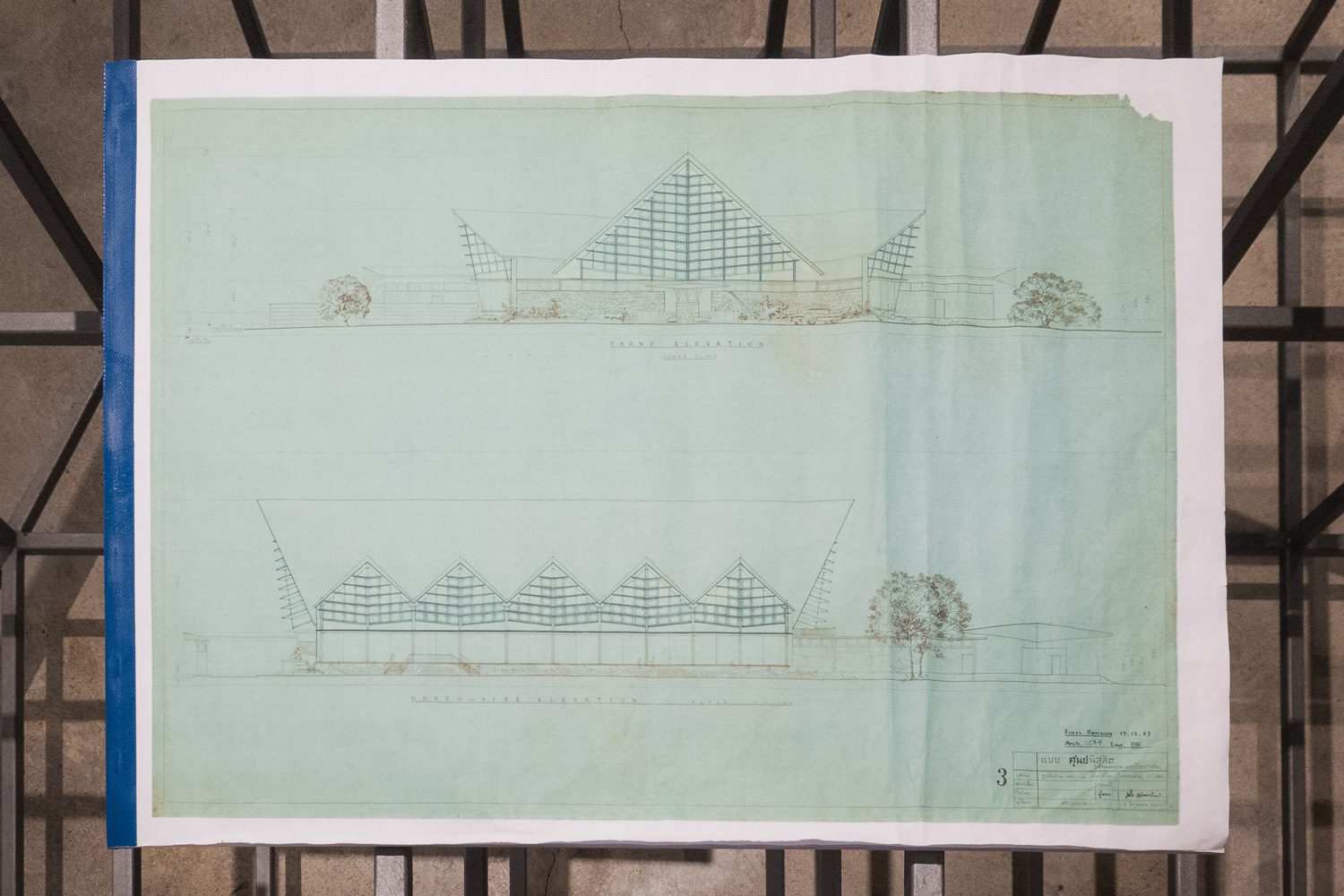

Picturing Modernity, an exhibition curated by Associate Professor Pirasri Povatong, Ph.D., with Krittee Wongmaneeroj as curatorial assistant, brings together selected works by these three photographers. The exhibition offers both a quantitative and qualitative perspective on modern architecture and its relationship with everyday life, set against the broader social, cultural, economic, and technological context of Bangkok from the 1950s through the 1970s.

The ‘images’ of modern architecture presented in this exhibition are manifold. They are diverse, hybrid, and layered with temporal complexity. They reflect relationships between past and present that are, at times, continuous and fluid, at others, conflicted or reoriented, and occasionally suggestive of questions yet to be answered about the future. These images also serve as a reminder that the definitions or conditions of modernity, and the forms and meanings of modern architecture in Bangkok, in Thailand, or in any context beyond the West, need not replicate those of the Western world, long assumed to be the origin of such frameworks.

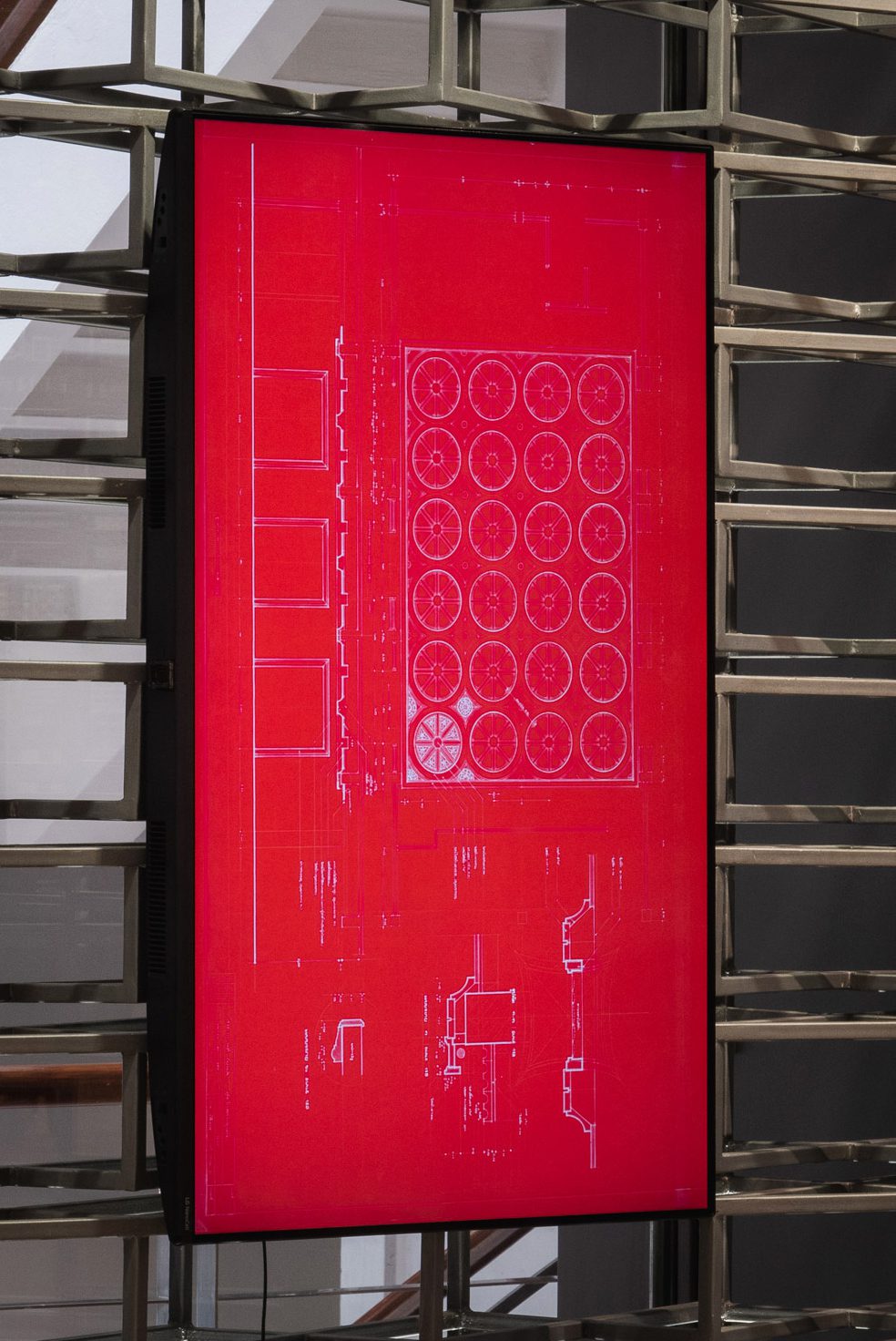

In the section devoted to Rabil Bunnag, a juxtaposition of two photographs from the 1950s, one of Wat Benchamabophit Temple and the other of a steel crane at Khlong Toei Port, reveals distinct aspects of modernity in both form and function. Wat Benchamabophit embodies an early 20th-century endeavor led by HRH Prince Narisara Nuvadtivongs in collaboration with a group of Italian architects and engineers to articulate a modern Thai architectural language. By contrast, Khlong Toei Port represents a monumental modern infrastructure project, designed to support national economic development, and completed only after delays caused by the Second World War.

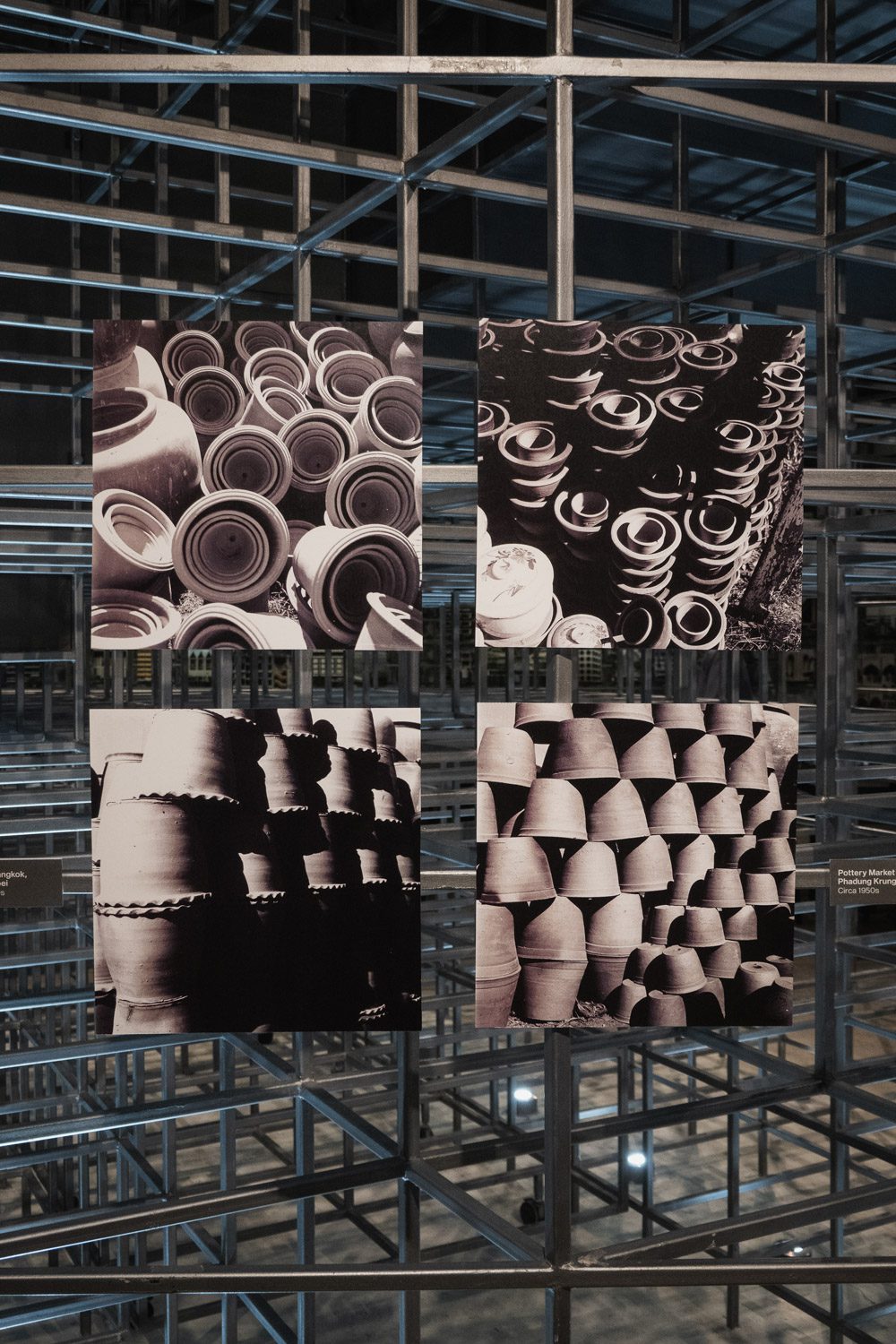

A photograph by Rabil Bunnag depicting a stack of terracotta pots in a market in Bangkok’s old town evokes the work of avant-garde Hungarian photographers from the pre–Second World War era, such as Ernö Vadas and André Kertész. Much like their images, in which objects or figures drawn from traditional societies were composed and lit in ways never seen before, Bunnag’s photograph reinterprets the everyday through a strikingly modern lens.

Also featured in the exhibition are numerous photographs of buildings from the 1950s. One such image captures the Thai Wattana Panich publishing house (now the Bangkok Kunsthalle building), whose street-facing façade appears washed in stark sunlight, rendering it a near-blank plane of white. This sharply contrasts with the actual surface material, which, like the building’s corner elevation, is finished in grey-tinted exposed aggregate, grooved to resemble a load-bearing stone wall in the manner of Western classical architecture. Another photograph shows the former Union Bank of Bangkok building (now Samitivej Chinatown Hospital) at the head of Yaowarat Road. Towering over its neighbors, the building exudes solidity and trustworthiness through its symmetrical form. The pediment-like feature atop its main façade recalls Western classicism, while the oversized pilasters flanking its expansive glass windows are capped with Thai-style capitals. The overall composition, merging international modernist sensibilities with culturally specific references, recalls certain postmodern works by Philip Johnson or Michael Graves. And yet, this is unequivocally a modernist building, designed by Mom Chao Samai Chalerm Kridakara more than two decades before such American structures came into being.

Photo: Chomchon Fusinpaiboon

The Thai dimension in modern architecture, as captured through Rabil Bunnag’s lens, is also visible in buildings such as the Royal Thai Police Headquarters and the main auditorium at Kasetsart University, where adapted Thai architectural elements are woven into modern forms. Yet perhaps the most compelling image in the exhibition, and arguably one of its highlights, is his photograph of the Jim Thompson House under construction. Scattered panels of traditional timber cladding (fa pakon) appear both on the ground in the foreground and on the partially assembled structure itself, forming the visual focal point of the composition. Strictly speaking, this is not construction in the conventional sense. Rather, it is the ‘reassembly’ or ‘re-cooking’ of architectural fragments; components of century-old Thai houses sourced from various regions, into a newly configured dwelling intended to accommodate a modern way of life in the 1950s. The image seems to pose a direct challenge to a longstanding question in Thai architectural and cultural discourse: how might Thai identity be meaningfully integrated into modern architecture? In this instance, one possible answer is by presenting modernity through a construction system akin to prefabrication, a technique long embedded in traditional Thai architecture.

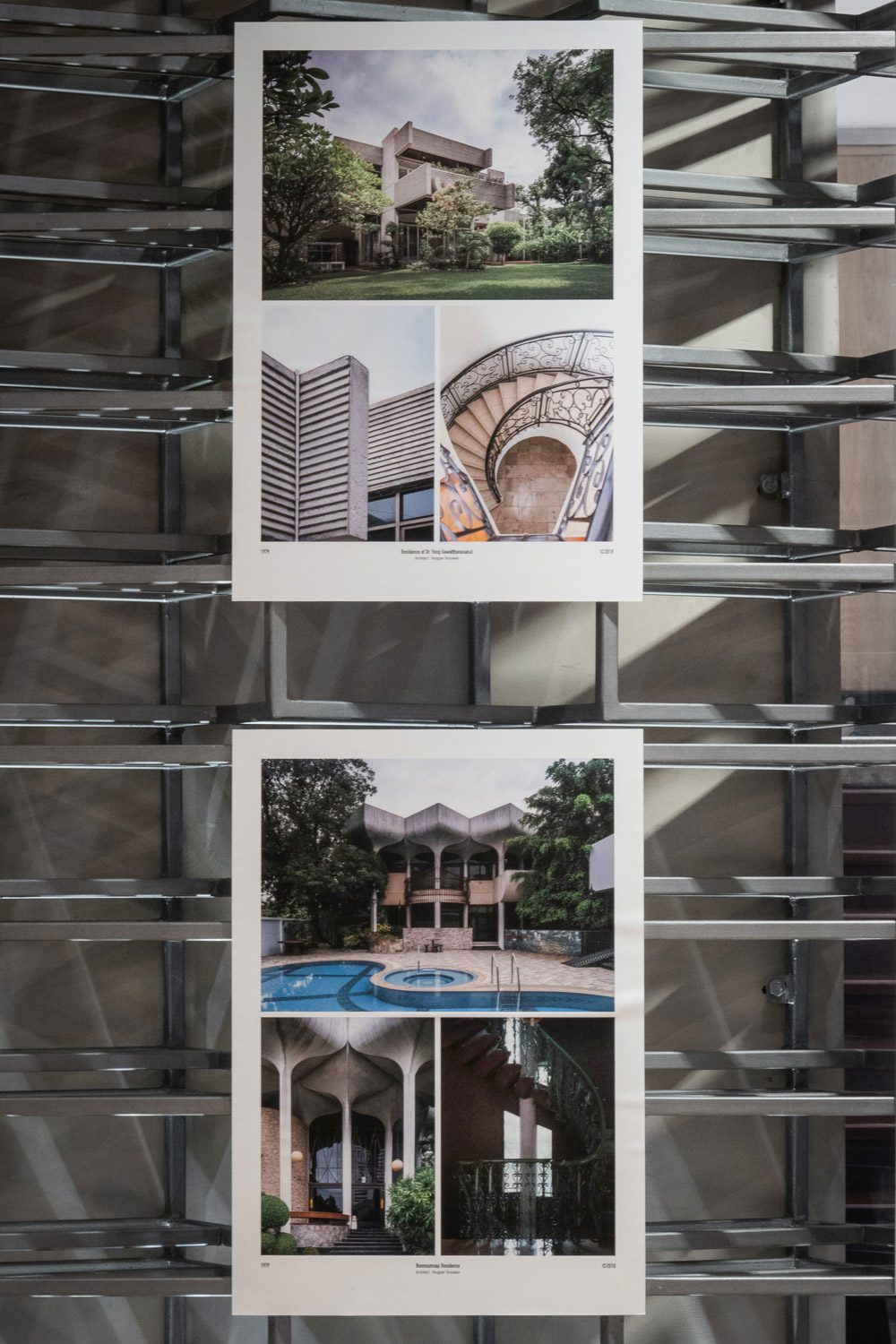

A similar line of inquiry, regarding the identity of modern architecture and the modern Thai city, and how these differ from mainstream Western paradigms, can be found in several photographs by Weerapon Singnoi. These include images of Dr. Yong Uahwatanasakul’s house and the Boonnumsup House, both designed by Rangsan Torsuwan in 1979. The buildings’ formal language and primary materials might lead many to classify them as Brutalist. And yet, both feature delicately curving staircases and ornamental wrought iron railings that veer toward Western classicism—details unlikely to appear in the residential projects designed by Denys Lasdun or Paul Rudolph.

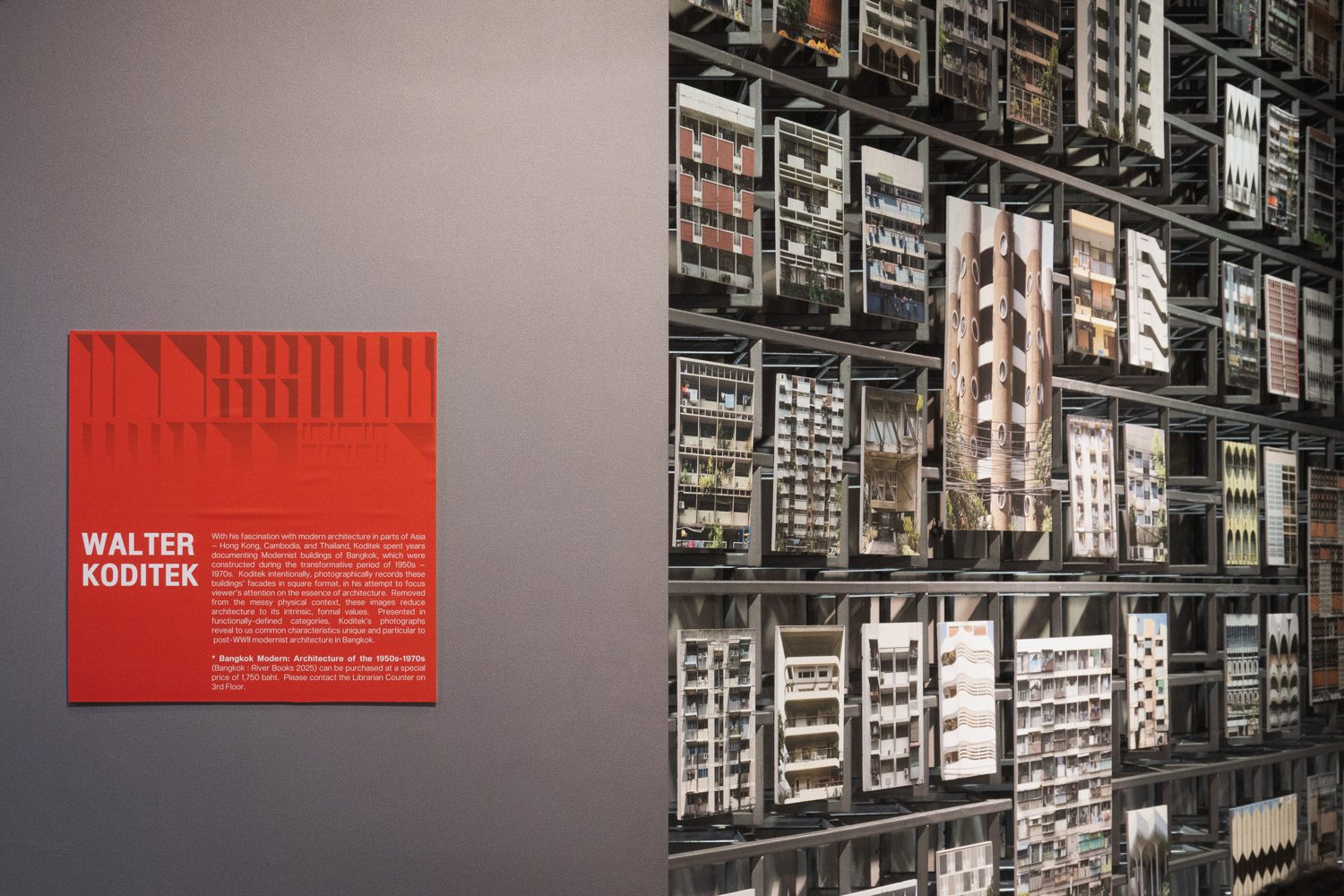

Walter Koditek’s presentation of numerous building façades centers on one distinctively recurring architectural feature: the exterior envelope, often referred to in mainstream architectural discourse by the catch-all term ‘sun-shading devices.’ Yet, as his photographs suggest, these elements are far from uniform. They reveal a surprising degree of variety, cultural specificity, and even playfulness. In the end, such features may not serve solely to block sunlight; some may do so poorly, or perhaps too effectively. Some function structurally, while others exist purely for aesthetic ornamentation. So long as we resist a rigid adherence to the modernist doctrine that dismisses ornamentation as a violation of architectural integrity.

Koditek’s section of the exhibition immerses viewers in a modernist cityscape, one populated by buildings designed in accordance with international standards of modern living, yet embedded with distinct local character and charm. These are the very buildings, many of which still exist today, that have shaped the physical fabric of inner and middle Bangkok since the 1970s. If cared for, restored, and thoughtfully adapted to contemporary needs, they could play a powerful role in shaping a renewed identity for Bangkok—one grounded in its own past. It may be a stretch, or at least an imperfect comparison, to suggest that these buildings could define urban identity in the same way that Haussmannian apartment blocks have in Paris, or Eixample blocks in Barcelona. A more fitting analogy might be London, where the architectural landscape is composed of an eclectic mix; predominantly Victorian structures interwoven with old and new buildings of various scales, forming a positive, layered urban identity in its own right.

Through a carefully curated viewing experience that invites close attention to the architectural details of modern Bangkok, the exhibition, Picturing Modernity: Photography and the Memory of Modern Bangkok, offers something that scrolling through images on a screen or flipping through a book simply cannot replicate. The exhibition is held at the Library Building, 2nd Floor, Faculty of Architecture, Chulalongkorn University, from 13 May to 13 June 2025. Opening Hours: Monday to Friday: 8:30 AM to 10:00 PM. Saturday: 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Closed on Sundays and public holidays.