A DUAL VILLAGE SHOWS INNOVATIVE ADAPTATION AMID INDUSTRIAL ADVERSITY, DOCUMENTED BY ARCHITECTS JENCHIEH HUNG AND KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE OF HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH

TEXT: JENCHIEH HUNG & KULTHIDA SONGKITTIPAKDEE

PHOTO: HAS DESIGN AND RESEARCH

(For Thai, press here)

Suan Oi Railway Dust Village, as featured in their latest book Chameleon Architecture: Shifting / Adapting / Evolving, facing pollution from a nearby concrete factory, has seen residents fortify their homes using low-cost materials to create protective bunkers. Conversely, the village’s abandoned railway side has been transformed into vibrant communal spaces. This dual approach, both defensive and open, illustrates grassroots evolution.

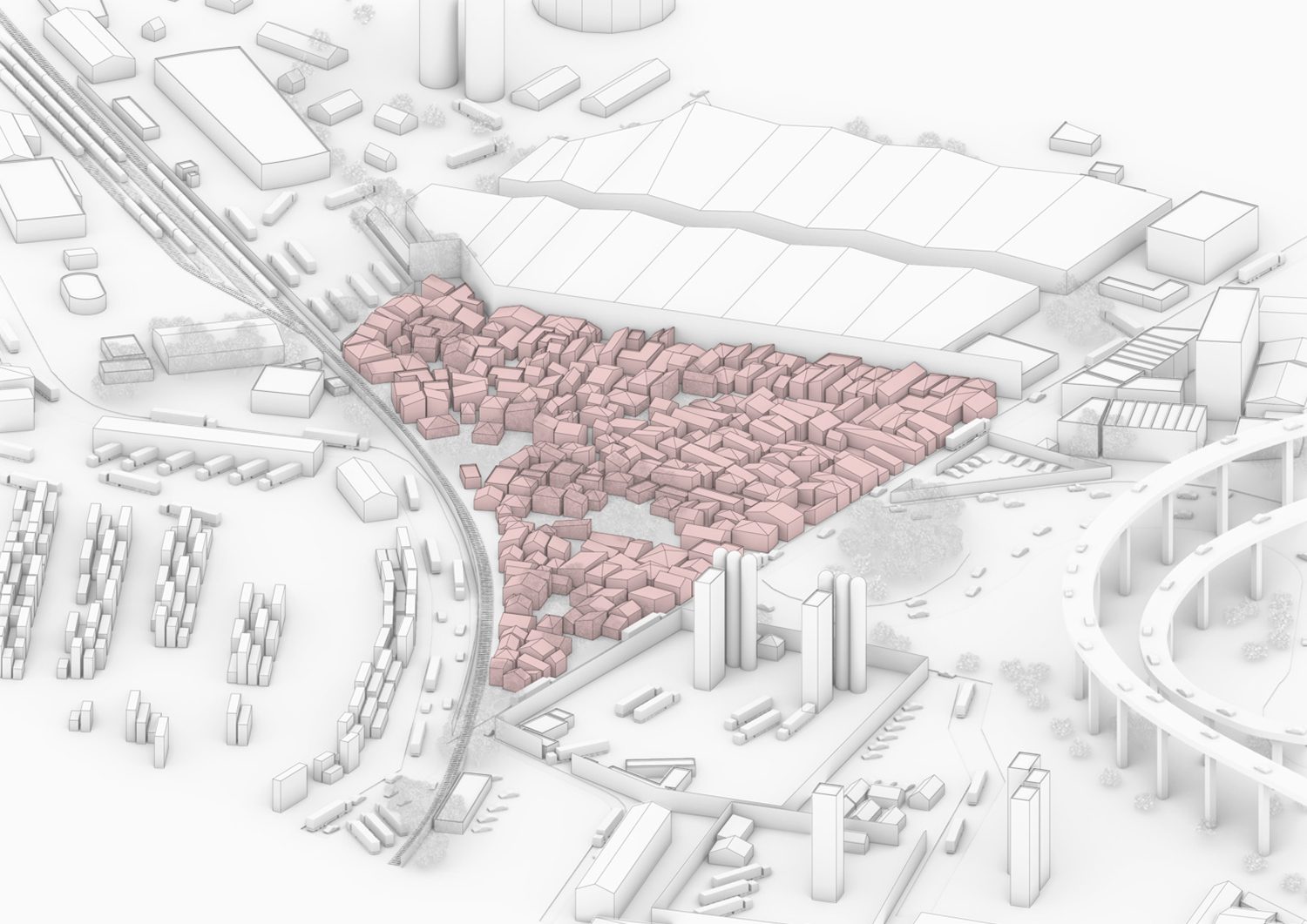

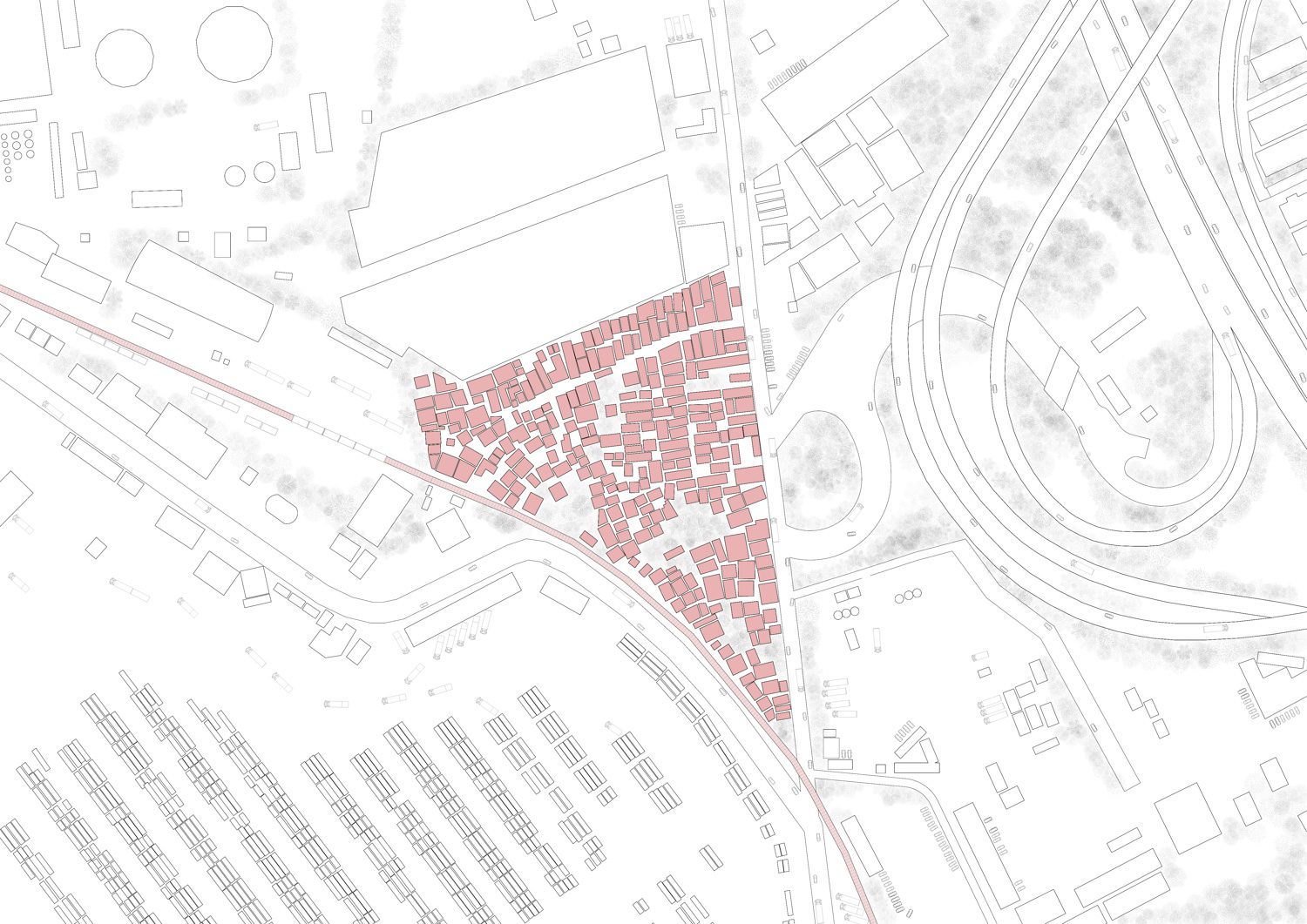

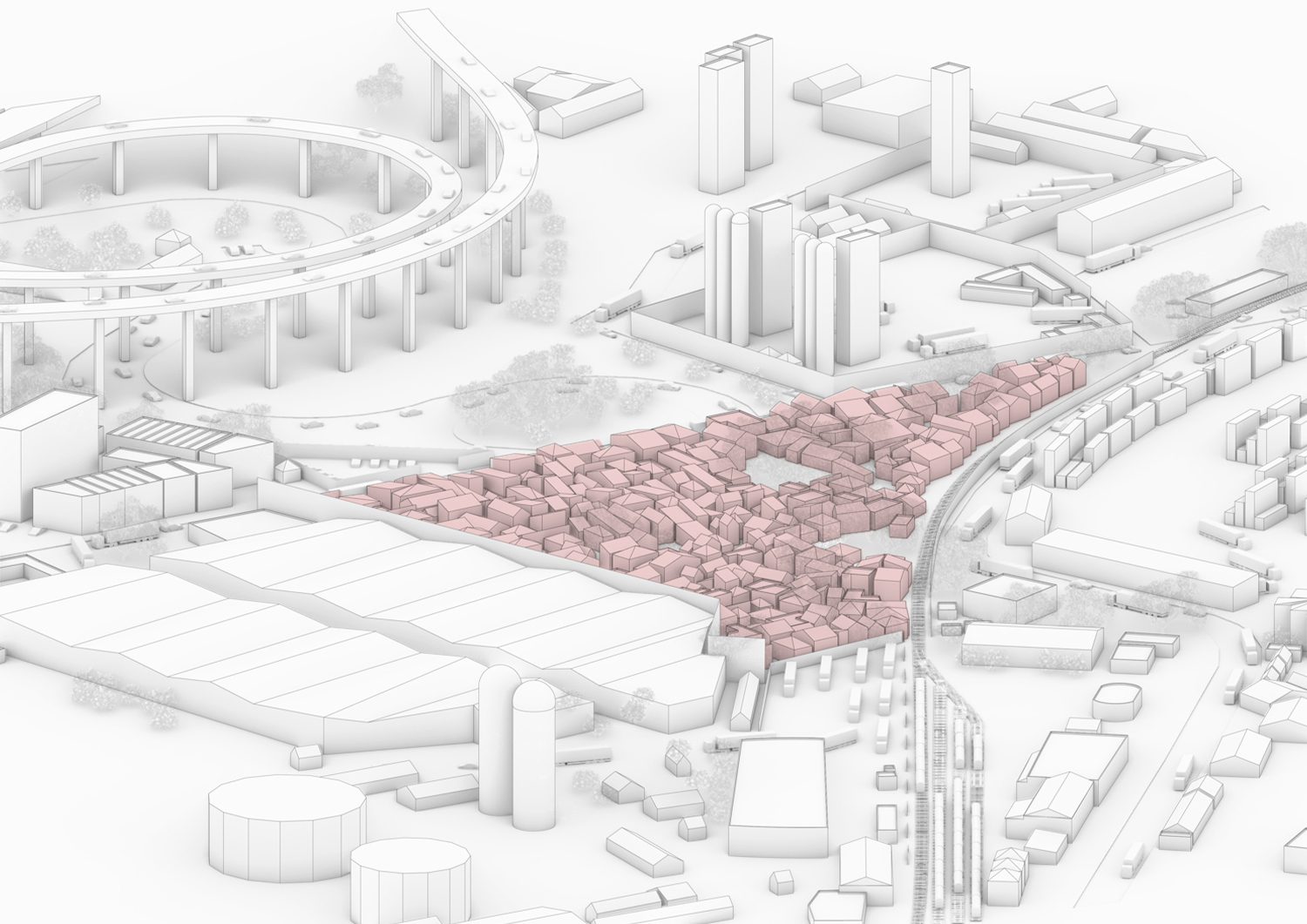

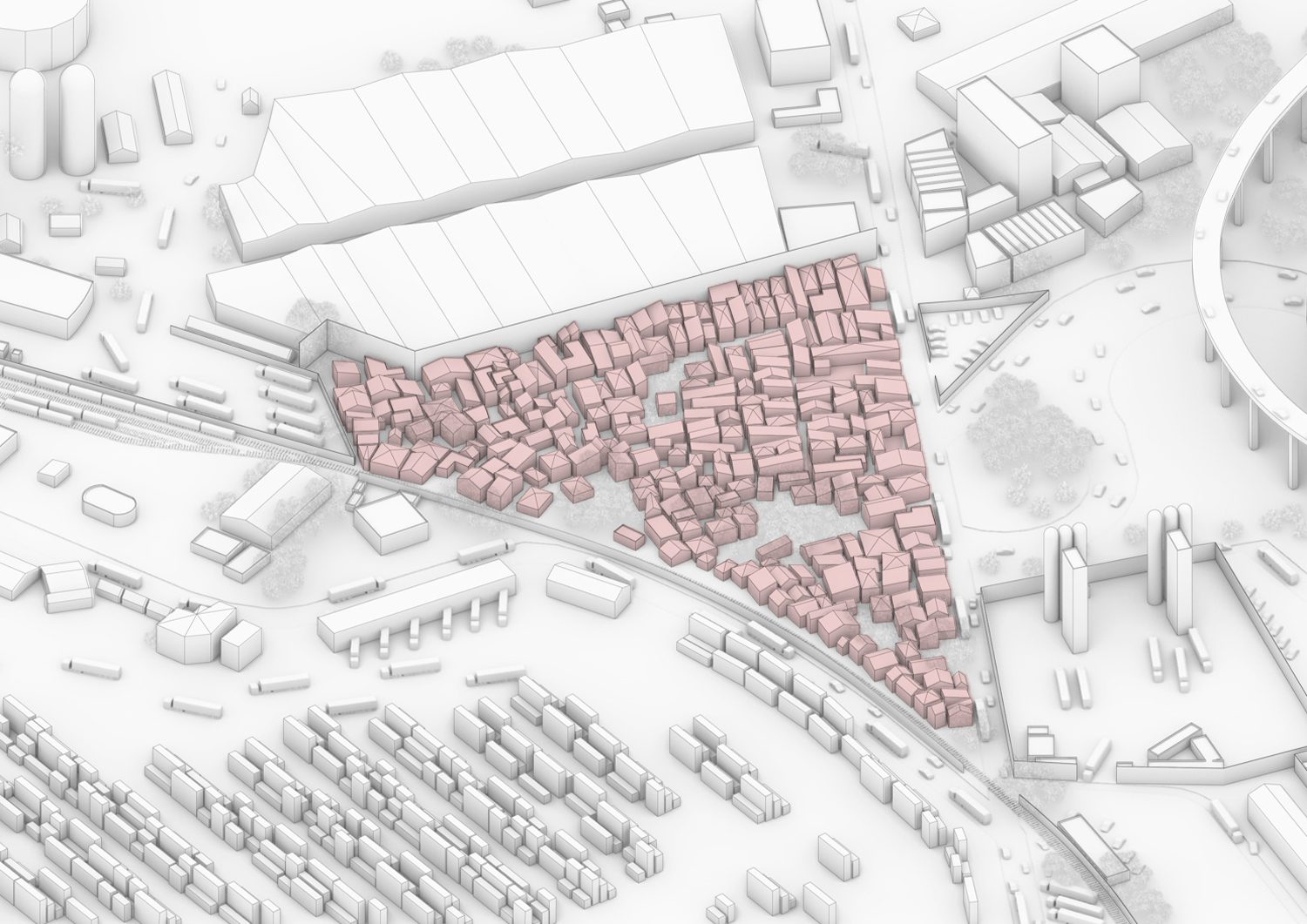

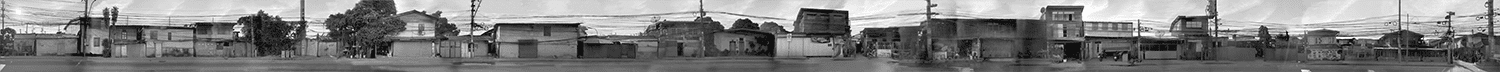

Located in Bangkok’s Phra Khanong district, Suan Oi Railway Dust Village presents a compelling site for research in architectural adaptation, resilience, and community formation amid urban and industrial adversity. Situated between a concrete factory and an abandoned railway line, the village embodies two contrasting yet complementary responses: defensive insulation against pollution and open communal engagement through reclaimed green railway space. Based on site research conducted by architects Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee of HAS Design and Research, and viewed through the lens of architectural research and community dynamics, the concept of adapting encapsulates the village’s dual nature: protective yet communal, isolated yet connected, defensive yet welcoming.

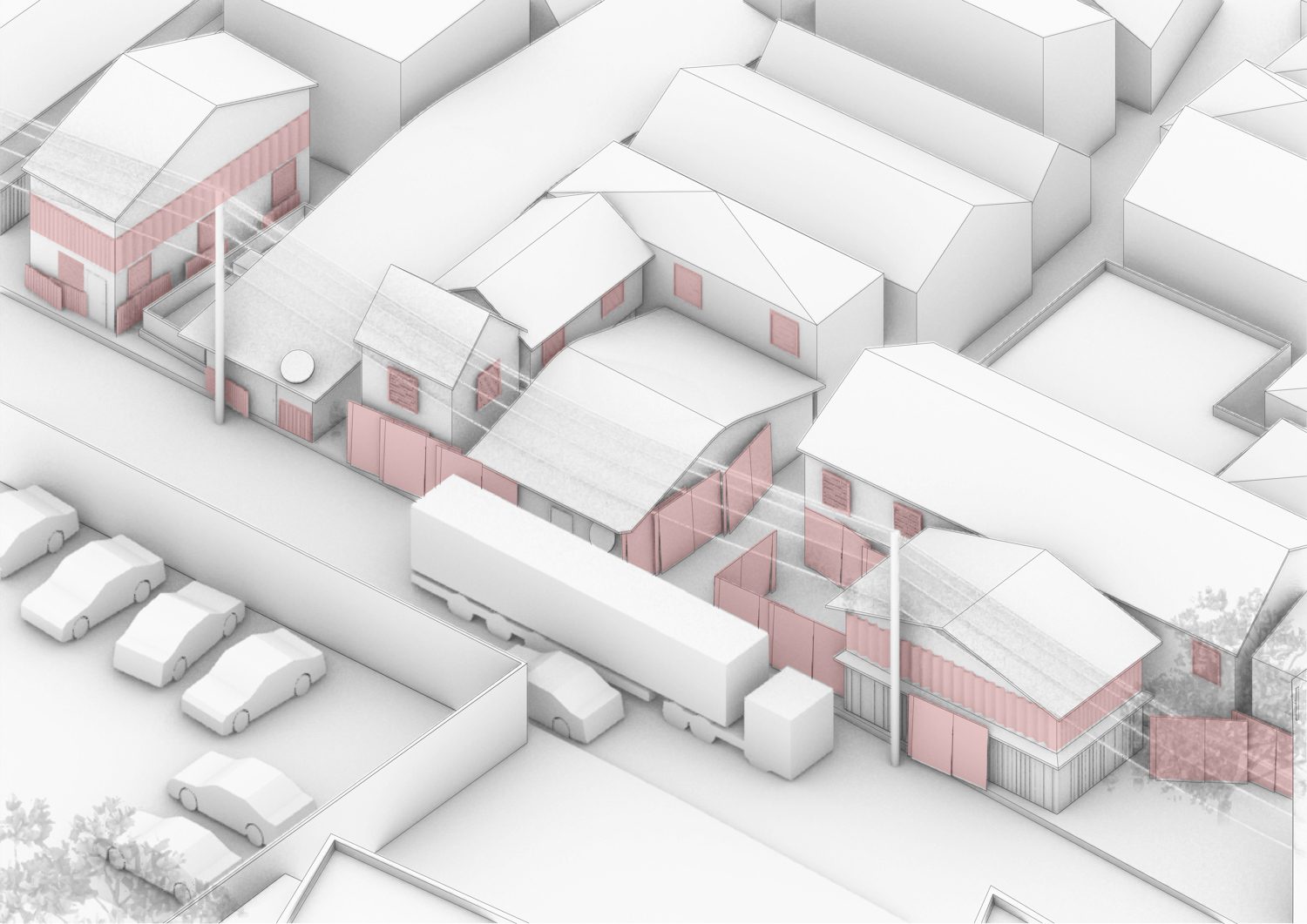

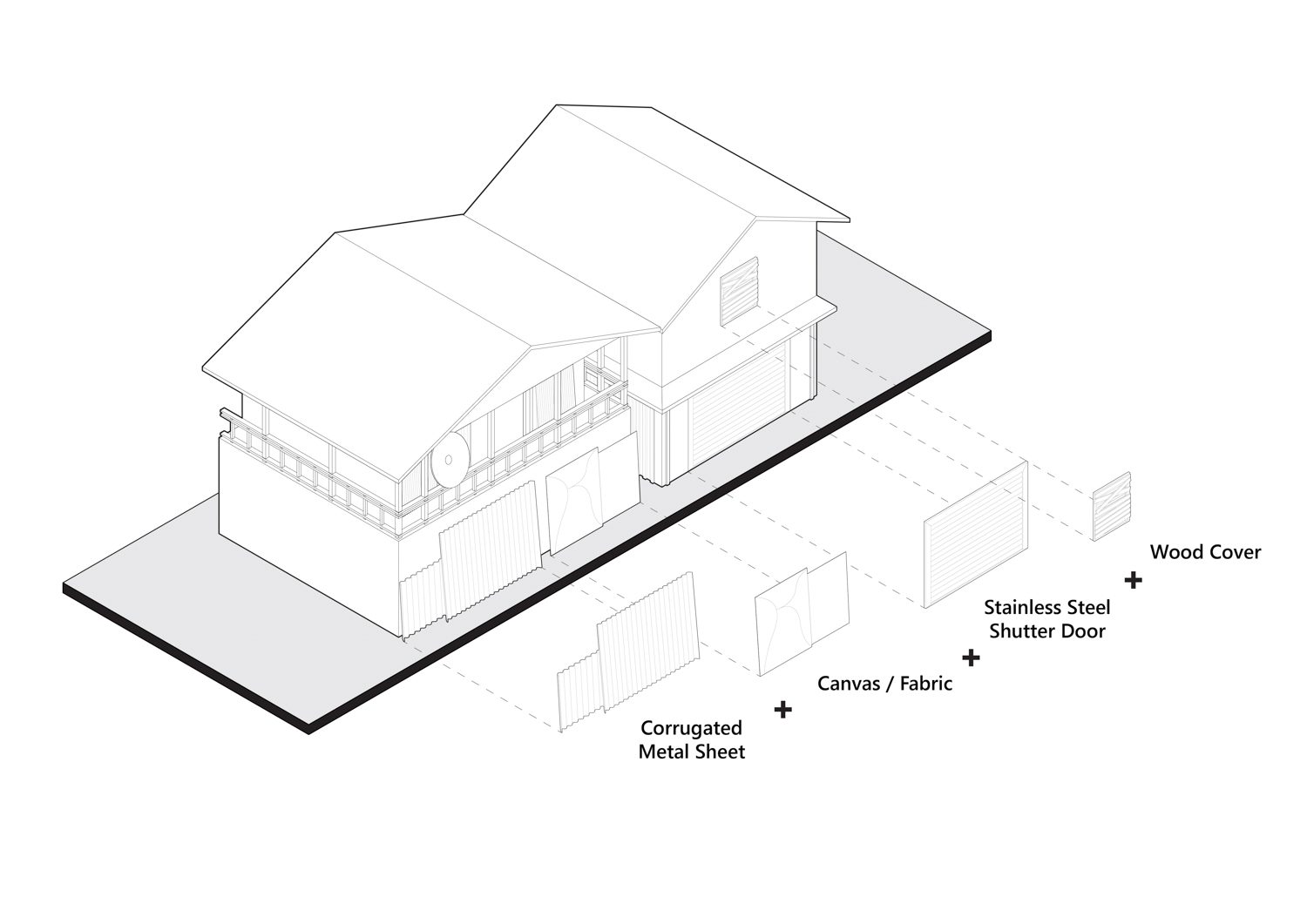

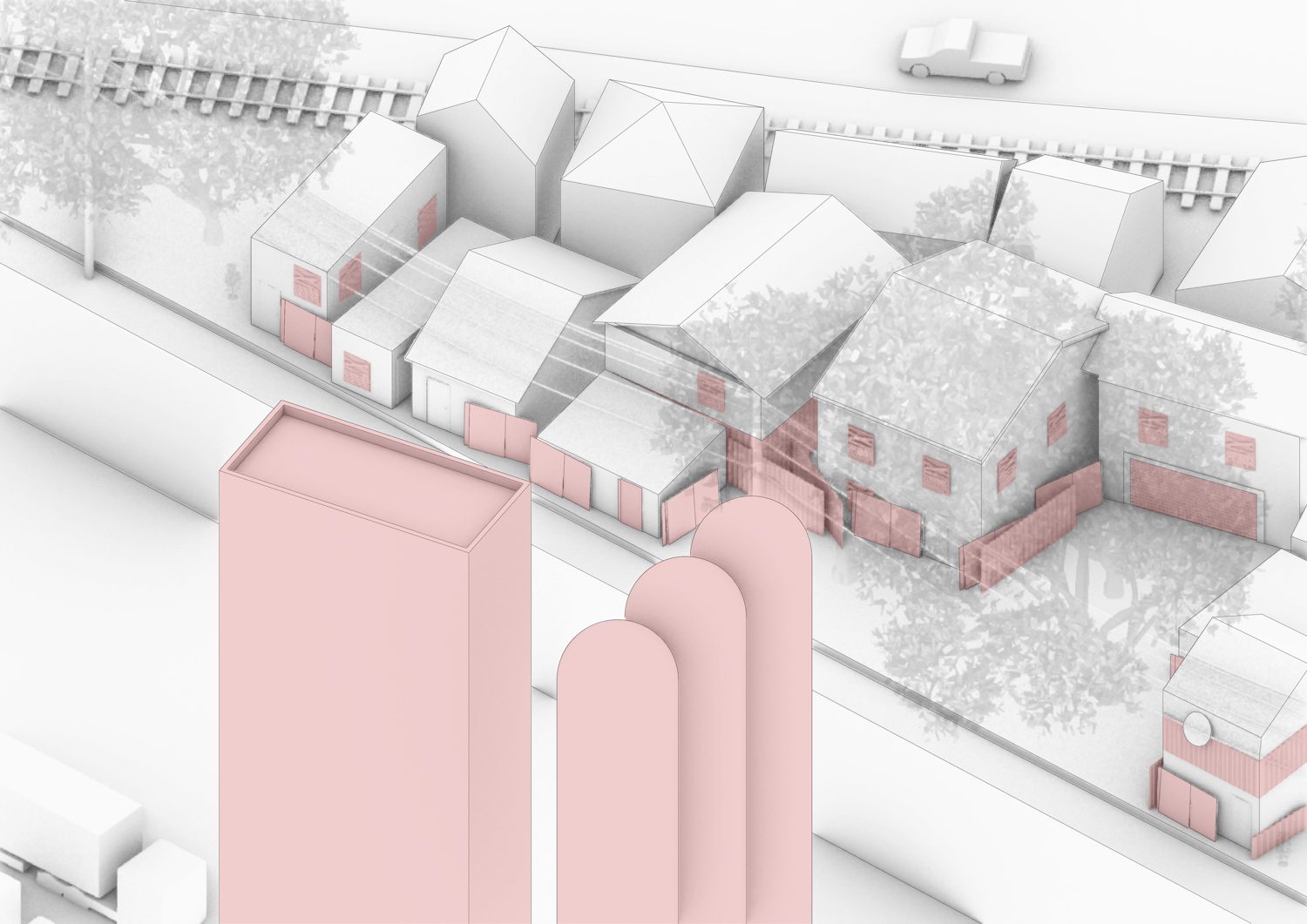

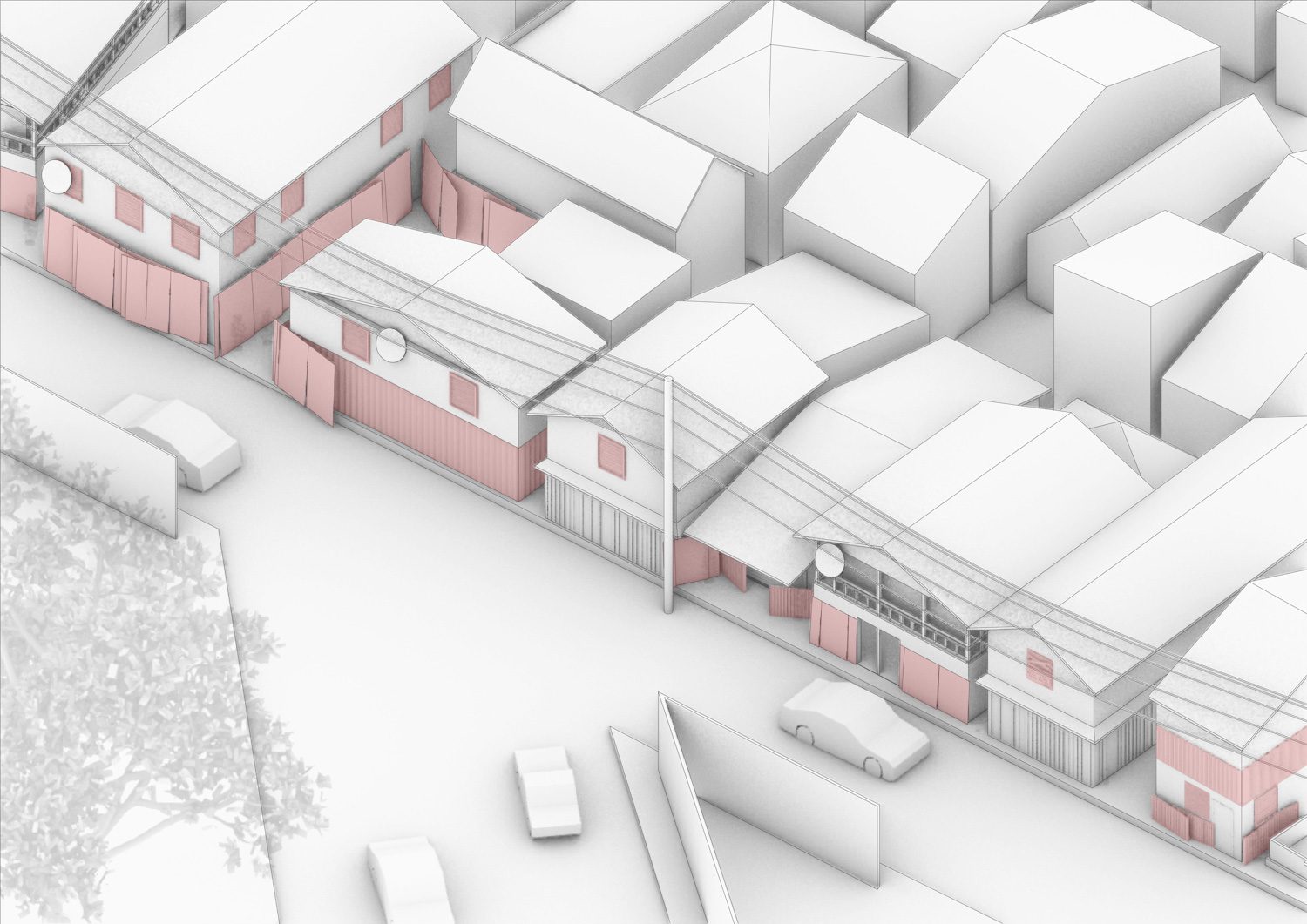

On the side connected to the public road, the village faces a cement factory that generates constant dust and toxic by-products. Dozens of gravel and sand trucks pass through daily, further exacerbating environmental degradation. In response, residents have transformed their homes into protective enclosures. Using low-cost, locally sourced materials—wooden boards, PVC fabric, and corrugated metal sheets—they have sealed windows and facades, creating bunker-like structures that shield them from pollution. These adaptive facades prioritize health and safety, forming a physical barrier between the community and the hostile industrial environment.

In stark contrast, the opposite edge of the village—bordering a defunct railway line—has been reclaimed by residents and transformed into a vibrant communal hub. The old tracks now host kitchens, laundry areas, seating, and gardens, complete with washbasins, furniture, and flourishing greenery. A large tree at the center serves as a natural gathering point, with all homes oriented toward it, reinforcing a shared sense of community. This space functions as an informal extension of domestic life, blurring the boundaries between private and public.

While the facades facing the factory are closed, fortified, and introspective, the railway side opens up to interaction, exchange, and everyday rituals. The coexistence of these spatial strategies illustrates how architecture responds not only to physical needs but also to social and emotional well-being.

This Dust Village operates through what can be described as synchronized moments of duality. One face is secluded and protective—an architectural response to environmental threat. The other is open and welcoming—a grassroots expression of social cohesion. This duality can be likened to a two-faced entity: on one side, a veiled bride, shielded from intrusion; on the other, a vibrant, living community gathering beneath a grand tree. These contradictions are not in conflict, but rather exist in harmony, reflecting the village’s remarkable adaptability. The sealed facades are not merely defensive—they symbolize resilience and autonomy. Meanwhile, the communal railway corridor speaks to the residents’ enduring desire for connection and shared experience, even in the face of adversity.

Suan Oi Railway Dust Village in Bangkok, Thailand, offers a powerful narrative at the intersection of architecture, community, and environmental resilience. It illustrates how built environments can evolve through grassroots innovation, responding not only to industrial threats but also to the intrinsic human need for connection and belonging. Viewed through the lens of architectural research, this village transcends the notion of mere urban survival and stands as a model of adaptive resilience. It reflects a broader movement in sustainable urbanism where architecture must both protect and connect, isolating when necessary but always seeking to invite collective life. Suan Oi Railway Dust Village is not defined by its hardships but by its response to them, a spatial synthesis of defense and openness, resilience and solidarity, as globalization continues to move forward.

This article content is an excerpt from the book ‘Chameleon Architecture: Shifting / Adapting / Evolving,’ authored by Jenchieh Hung & Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS design and research, available for purchase at: https://art4d.com/product/chameleon-architecture

facebook.com/hasdesignandresearch

instagram.com/has.design.and.research