AT THE BACC’S ‘EARLY YEARS PROJECT #4’ THIS YEAR, THE TERM AMBIGUITY SEEMS TO PLAY MORE IMPORTANT ROLE THAN THE EXACT MEANING OF THE WORKS

TEXT: SUTEE NAKARAKORNKUL

PHOTO: NAPAT CHARITBUTRA

(For English, please scroll down)

โครงการ Early Years Project ในปีนี้ จัดขึ้นระหว่างวันที่ 10 พฤษภาคม – 28 กรกฎาคม ที่ห้องนิทรรศการหลัก ชั้น 7 หอศิลปวัฒนธรรมแห่งกรุงเทพมหานคร ภายใต้ชื่อ Praxis Makes Perfect หรือ “ความสำเร็จเกิดจากการฝึกฝน” โดยมี พอใจ อัครธนกุล พงศกรณ์ ญาณะณิสสร และณัฐ ศรีสุวรรณ รับหน้าที่เป็นผู้คัดเลือกและกรรมการตัดสินผลงานจากศิลปินทั้งหมด 8 คนที่เข้าร่วมโครงการ วัตถุประสงค์หลักของ Early Years Project คือการเป็นเหมือนกับพื้นที่ทดลองที่เปิดโอกาสให้ศิลปินได้จัดแสดงผลงาน พร้อมไปกับการค่อยๆ พัฒนาชิ้นงานจากแนวคิดตั้งต้นของตัวเองในระหว่างโปรแกรมการจัดแสดงของโครงการ

ข้อความท่อนหนึ่งจากคำอธิบายนิทรรศการที่ติดอยู่บนฝาผนังเล่าถึงวิธีการทำงานของศิลปินภายในโครงการว่า “ไม่เพียงแต่จำกัดการทำงานเพื่อพื้นที่กล่องขาวของห้องนิทรรศการเท่านั้น แต่ต้องการอ้างอิงถึงความเป็นไปได้อื่นๆ นอกเหนือจากนี้ด้วย” ความเป็นไปได้ที่ว่าก็คือ การทำงานแบบ “สหวิทยาการ” หรือการนำองค์ความรู้จากศาสตร์แขนงอื่นๆ มาเชื่อมโยงและประยุกต์ใช้ในการทำงานศิลปะเพื่อเปิดรับมุมมองและระเบียบวิธีคิดที่ต่างออกไป

อย่างไรก็ตาม เมื่อศาสตร์แต่ละศาสตร์ก็มีกรอบและมุมมองเฉพาะเป็นของตนเอง “การข้ามสาขา” จึงดูเป็นเรื่องที่ไม่ง่ายนัก ยิ่งไปกว่านั้น เมื่อมันเข้าไปพาดพิงและประกอบขึ้นจากหลายอย่าง ความชัดเจนที่หลายๆ คนต้องการให้ศิลปะ “มี” ก็อาจกลับกลายเป็นความคลุมเครือ Day Barber Shop, 2019 งานอินสตอลเลชั่นโดย วรวุฒิ ช้างทอง ตั้งคำถามถึงความคลุมเครือของเส้นแบ่งระหว่างความเป็นศิลปินและความเป็นช่าง ด้วยการเปลี่ยนพื้นที่โซนหนึ่งของห้องนิทรรศการเป็นร้านตัดผมชาย เอาเก้าอี้บาร์เบอร์มาตั้งบนสเตจที่ยกพื้นสูงกว่าระดับปกติเล็กน้อย และเปิดรอบบริการตัดผมฟรีในทุกๆ สัปดาห์ ระหว่างการตัดผมนี้เองจารีตพื้นฐานของหอศิลป์อย่างการห้ามจับวัตถุก็พังทลายลง เพราะงานศิลปะของเขากลายเป็นกิจกรรมและเหตุการณ์ที่ผู้ชมกลายเป็นตัวแสดงที่ทำบางอย่างให้เกิดขึ้น

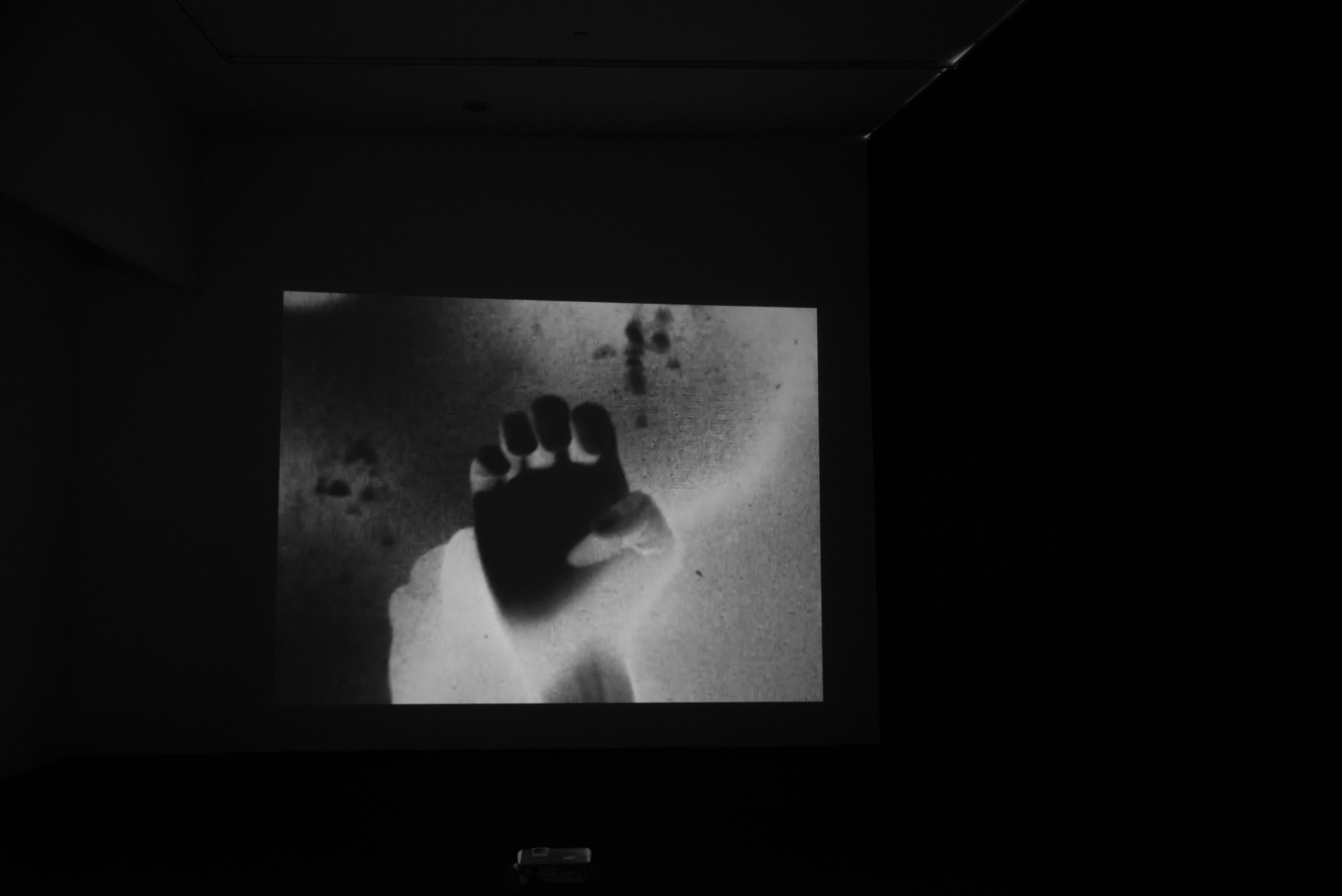

ในลักษณะที่คล้ายคลึงกัน Eye your ears, 2019 โดย จัน เพ็ญจันทร์ ลาซูส ปล่อยให้คนดูค่อยๆ แกะความหมายจากผลงานกันเอง ในวิดีโอ two-channel film installation ขาวดำสองชุด ที่เริ่มต้นจากการตั้งคำถามของศิลปินเกี่ยวกับการจินตนาการผ่านภาษาที่คนทั่วไปไม่คุ้นเคย และความเป็นไปได้ที่ซ่อนอยู่ในความหมายอันคลุมเครือของภาษามือไทย (Thai Sign Language – TSL) ที่ศิลปินได้ทำงานร่วมกับคนหูหนวกและหูตึง

นอกจากนี้ยังมีผลงานอีกส่วนหนึ่งที่พูดถึงการบันทึกช่วงเวลาและความทรงจำ Capital Memorial, 2019 ของ กรธนัท พิพัฒน์ เป็นชุดภาพถ่ายที่ศิลปินได้บันทึกภาพของสิ่งปลูกสร้างต่างๆ ที่เป็นเหมือนอนุสรณ์สถานของกรุงเทพฯ เพื่อนำเสนอถึงการเปลี่ยนแปลงทางกายภาพของเมือง โดยมีประเด็นต่างๆ ที่ซ้อนทับกันอยู่ เช่น เศรษฐกิจ สังคม และการเมือง เริ่มจากภาพบ้านร้างนิรนาม ไปสู่สถานที่ที่คนรู้จักเป็นอย่างดีอย่าง ซากของโครงการระบบการขนส่งทางรถไฟยกระดับภายใต้การดำเนินงานโดยบริษัทโฮปเวลล์ ไฮไลท์ของงานชุดนี้คือสื่อกลางที่ใช้ในการติดตั้งภาพถ่าย การขูดขีดให้ผนังติดตั้งงานมีร่องรอยของการผุพังและปรากฏเศษซากตกหล่นกองอยู่บนพื้น ขับเน้นถึงความล่มสลายและพังทลายลงของบางอย่างได้อย่างชัดเจน ส่วน I always think of you fondly, 2019 เป็นงานอินสตอลเลชั่นที่ ทิวไพร บัวลอย ชำแหละฮาร์ดดิสก์แล็ปท็อปออกมา และแยกชิ้นส่วนพวกมันไว้ในตู้กระจกที่ซ้อนกันเป็นทางยาวหลายๆ เลเยอร์ เพื่อพูดถึงความเปราะบางของข้อมูลดิจิตอลและความเปราะบางของวัสดุที่ทำหน้าที่ในการบันทึก จากอุบัติเหตุของศิลปินที่พบว่าไฟล์วิดีโอและภาพถ่ายในอดีตของเขานั้นได้สูญหายไป และไม่สามารถกู้คืนกลับมาได้ ทิวไพรพูดถึงแนวคิดในงานชิ้นนี้ของเขาว่า “สิ่งที่ค้นเจอในงานชิ้นนี้คือการทำความเข้าใจว่ามันไม่มีอะไรดำรงอยู่ไปโดยตลอด ซึ่งดูมีความเป็นมนุษย์มากๆ” ความเป็นมนุษย์ที่ว่าก็คือการยื้อยุดกับการสูญสลาย และทำอย่างไรเพื่อให้ทุกๆ อย่างมีอายุนานขึ้น

กลับมาที่โปรแกรมของนิทรรศการ การจัดแสดงผลงานภายในโครงการนี้ถูกแบ่งออกเป็น 3 เฟส กินระยะเวลากว่า 11 สัปดาห์ เพื่อเปิดโอกาสให้ศิลปินได้พัฒนาผลงานของตนเอง โดยระหว่างนั้นจะมีกิจกรรมการศึกษา NEXT STEPS ที่จัดขึ้นเป็นกิจกรรมเสริมนิทรรศการ ซึ่งประกอบไปด้วย กิจกรรมเวิร์คช็อปปิดที่ได้ผู้เชี่ยวชาญในสาขาต่างๆ มาร่วมแชร์ประสบการณ์การทำงาน และกิจกรรม Exhibition Talk การบรรยายที่เปิดให้บุคคลทั่วไปสามารถเข้าไปฟังได้ รวมไปถึงกิจกรรม Critic Session ที่จะช่วยฝึกฝนศิลปินรุ่นใหม่ให้คุ้นเคยกับวัฒนธรรมการวิจารณ์ เพื่อนำไปปรับใช้กับวิธีวิจัยและการทำงานของตัวเองต่อไป กิจกรรมต่างๆ ที่กล่าวถึงนี้ นับได้ว่าล้วนแล้วแต่เป็นปัจจัยสำคัญ หรือปัจจัยภายนอก ที่มา “กระทบ” ศิลปินและส่งผลให้เกิดการเปลี่ยนแปลงของผลงานในตลอดระยะเวลาทั้ง 3 เฟสของโครงการ

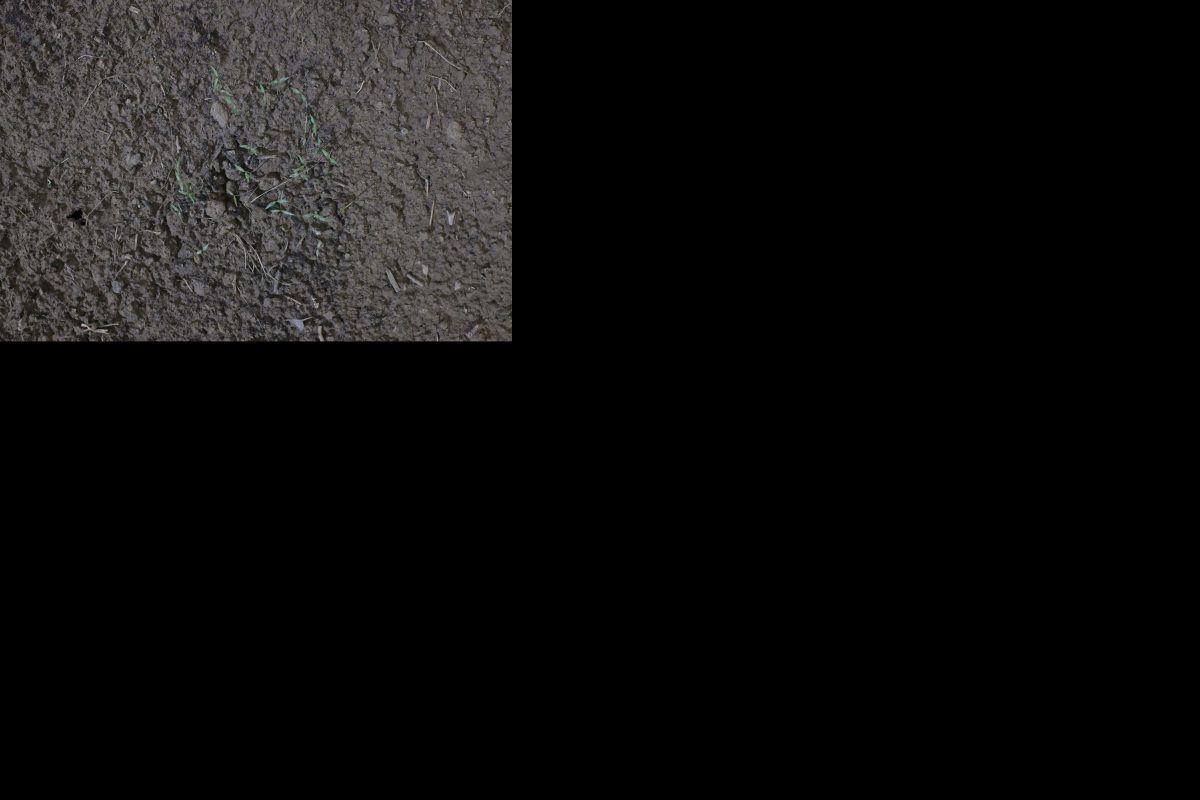

ในลักษณะเดียวกันกับกองดินในผลงาน Identity, 2019 ของ ปานวัตร เมืองมูล ที่จะงอกเงยเปลี่ยนรูปจากเดิมได้นั้นจำเป็นต้องได้รับการจัดการจาก “ปัจจัยภายนอก” (ในที่นี้คือน้ำ) งานชิ้นนี้เริ่มจากการตั้งคำถามของศิลปิน ว่าจริงๆ แล้วพุทธศิลป์คืออะไรในความหมายของตัวเอง จนนำไปสู่การสำรวจตัวเองทั้งทางกายภาพและทางจิตใจ และในแง่ของกายภาพ ศิลปินมองว่าร่างกายของคนเราเป็นการรวมตัวกันของธาตุต่างๆ ซึ่งธาตุดินดูจะมีความสำคัญเป็นพิเศษ เพราะเป็นแหล่งกำเนิดของสิ่งมีชีวิตที่มีวงจรบางอย่างเกี่ยวข้องกับการมีชีวิตและการเจริญเติบโต เช่น อาหาร พืช และสิ่งปฏิกูลของร่างกาย นอกเหนือไปจากแปลงพืชขนาดย่อมแล้ว ศิลปินก็ได้นำเศษปฏิกูลของ พ่อ แม่ และตัวเอง มาใ่ส่ไว้ในภาชนะที่มีหน้าตาคล้ายคลึงกับพระบรมสารีริกธาตุ และในเฟสที่สองของโปรแกรม ศิลปินได้นำตู้กระจกใสมาติดตั้งเพิ่มเติม โดยจัดวางจักรเย็บผ้าและชุดปฏิบัติธรรมไว้ภายใน จนตู้โชว์ข้าวของนี้เป็นเหมือนพิพิธภัณฑ์ความทรงจำของตัวเอง

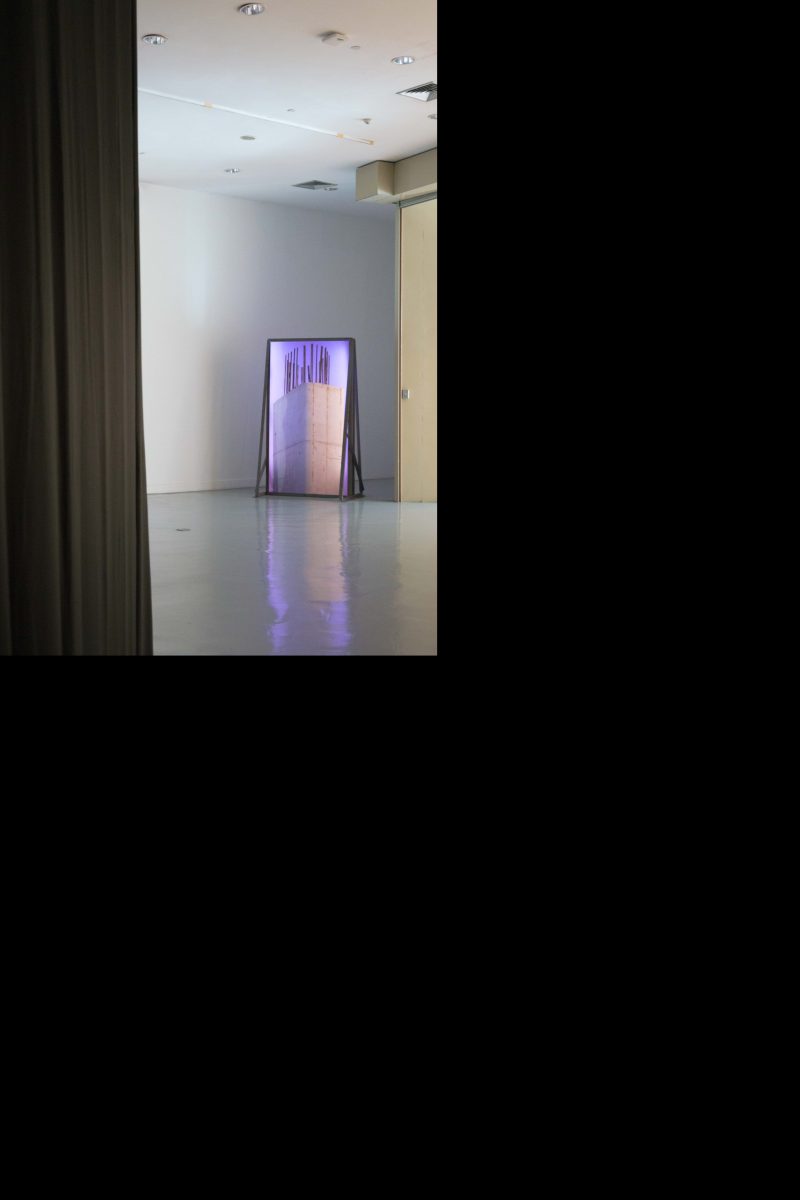

การเปลี่ยนแปลงในเชิงเซตติ้งของผลงาน ยังปรากฏให้เห็นอย่างชัดเจนในผลงานอีกชุดหนึ่งของ วิรดา บรรเจิดรุ่งขจร Find me a house, 2019 คือการพยายามบันทึกและปะติดปะต่อเรื่องเล่าเกี่ยวกับรากเหง้าและสถานะคนจีนพลัดถิ่นของครอบครัว ด้วยการอุปมาและสร้างพื้นที่ใหม่จากความทรงจำของยาย ในเฟสแรกของโปรแกรม วิรดานำข้อความจากหนังสือ เช่น quotes ของ Joanne Harris “I’ve never been very good at leaving things behind. I tried, but I have always left fragments of myself there too, like seeds awaiting their chance to grow.” มาทำเป็น concrete poetry ที่เรียงตัวกันเป็นรูปแปลนบ้าน เพื่อทำหน้าที่ในการตีขอบเขตของคำว่าบ้าน ผลงานเริ่มเปลี่ยนแปลงไปในเฟสที่สอง เมื่อวิรดาได้จัดวางโครงผนังไม้และอลูมิเนียมติดล้อราวกับโคลงกลอนบนผนังมีกายภาพงอกออกมาในสเปซห้อง การติดล้อมีข้อดีในแง่ที่มันสามารถเลื่อนขยับเพื่อขยายขอบเขตของบ้านตอนไหนก็ได้ แต่ก็ปฏิเสธไม่ได้ว่าทำให้ความสามารถในการ define space น้อยลงตามไปด้วยเช่นกัน

ยังมีผลงานของศิลปินคนอื่นๆ ที่เราไม่ได้พูดถึงในที่นี้ ความคลุมเครือ (ที่เรากล่าวถึงในข้างต้น) ที่ห้อมล้อมอยู่ในนิทรรศการอาจจะไม่ได้มีความหมายในเชิงลบเสมอไป เพราะสภาวะอันคลุมเครือก็มักเป็นสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นตามมาเมื่อเราต้องเข้าไปในพรมแดนที่ไม่คุ้นเคยอย่างไม่อาจหลีกเลี่ยง สิ่งที่ท้าทายและมองเห็นได้จากความคลุมเครือนี้ ก็คงจะเป็นความสามารถในการควบคุม “ความคลุมเครือ” ที่ทำให้งานศิลปะยังสามารถเล่าเรื่องได้อย่างมีชีวิตชีวา ไปพร้อมๆ กับการขยายนิยามของคำว่าศิลปะให้กว้างขึ้นกว่าเดิม

This year’s Early Years Project took place between 10th May and 28th July 2019 at the main exhibition room, on the 7th floor of Bangkok Art and Culture Center. Themed ‘Praxis Makes Perfect’, the event has Pojai Akratanakul, Pongsakorn Yananissorn and Nut Srisuwan as the jury responsible for selecting the 8 finalists and choosing the winning work. Early Years Project is initiated with the main objective being to serve as an experimental platform for artists to showcase their works from the early conceptualization stage before they gradually develop and evolve through different phases of the program.

An excerpt from the exhibition’s description describes the work methods of the artists participating in the project and how they do “Not only limit the working processes developed for the ‘white cube’ but wish to reference other possibilities.” Such possibilities include the interdisciplinary approach or the integration and application of different fields of study in the artistic process to embrace new perspectives and methodologies.

Nonetheless, with each science having its own framework and perspective, the interdisciplinary approach can be quite challenging especially when it involves and comprises of several elements. The clarity that many expect for art to have can become somewhat an obscurity. Day Barber Shop, 2019, the installation by Worawut Changthong, questions the obscurity of the boundary that separates artists from artisans. The work transforms a zone in the exhibition space into a barbershop with a number of barber chairs put on a stage slightly elevated from the ground floor. The shop opened every week throughout the duration of the program and offered free service for visitors. It was during these sessions of services that the norm of museum space, in which the touching of exhibited objects is normally prohibited, was destroyed. With Day Barber Shop, the artwork becomes an activity and incident that requires audience as an actor who enables or makes something happen.

Similarly, ‘Eye your ears,’ (2019) by Jeanne Penjan Lassus gradually welcomes viewers to work out the interpretation of the two-channel film installation, which features the screening of two different black and white videos. As a result of a collaborative process between the artist and a group of hearing impaired individuals, the work begins with the artist’s question about imagination using an unfamiliar set of language and the possibilities hidden in the obscurity of Thai Sign Language (TSL).

Another series of works talks about the documentation of time and memories. Titled ‘Capital Memorial,’ (2019), the series of photographs by Kornthanat Pipat captures the built structures known for their unofficial statuses as Bangkok’s memorial sites. The work portrays the changes in the physical conditions of the city’s urban spaces and overlapped economical, social and political issues. The series begins with a photograph of a deserted house of unidentified location and owner to the well-known places such as the remaining structure of the infamous Hopewell highway. The highlight of the series is the medium used for the installation of the photographs. As a part of the installation, the surface of the walls where the works are exhibited is scratched, creating details of deterioration with the fallen debris intentionally left on the ground—a tangible symbolization of the the fall and destruction of things. ‘I always think of you fondly,’ (2019) is an installation where Tewprai Bualoi dissects the hard disk of a laptop computer before display the dissembled parts in a long row of glass cabinets installed in superimposed layers. The work discusses the fragility of digital data and the materials used for storing it. The work takes the inspiration from the artist’s own experience when the videos and photographs he took were lost and cannot be recovered. “What I found through this work is an understanding in the impermanence of things, which is very human-like,” said Bualoi. The human-like he mentions refers one’s attempt to hold on the things that will eventually perish, and all the efforts people go through to extend the lives of everything around them.

The exhibition’s program is divided into 3 phases. Within the span of 11 weeks, the program allows the artists to develop their works with NEXT STEPS held as an additional activity, featuring workshops that invite experts from different disciplines to share their professional experiences and Exhibition Talk, which was open to the general public. Also included in the program is the Critic Session, which helps the young artists to be more familiar with the culture of critique, and allows them to learn to adapt the critics’ opinions to their future researches and works. The activities are considered as the outside yet important factors that influence the artists’ artistic processes, causing them to change and evolve throughout the three phases of the project.

Similar to the pile of earth in Pannawat Muangmoon’s ‘Identity,’ (2019), the changes were the result of an outside factor (water). The work is conceived from the artist’s question about the definition of Buddhist art, which leads to a process of his own physical and mental self-exploration. Looking at the physical aspect of it, the artist views human body as collection of different elements. The earth seems to be considered as the most important element for the way it’s the origin of living creatures with certain cycles needed for life and growth such as food, plants and body wastes. In addition to a small plot where a number of plants are grown, the artist puts the body wastes of his parents and himself in a utensil that looks similar to the shape of the Buddha’s relics. During the second phase of the program, the artist added a glass cabinet to the installation, and placed inside were a sewing machine and the white clothes commonly worn by faithful Buddhist disciples when attending religious ceremonies. The cabinet has become the museum of the artist’s own memories.

The changes in the setting is evident in Virada Banjurtrungkajorn’s ‘Find me a house,’ (2019). The work is the artist’s attempt to document and put together stories of her own root and the status of Chinese diaspora of her ancestors. Through a metaphorical presentation and recreation of a space from her grandmother’s memories, during the first phase of the program, the artist took a number of quotes from books such as Joanne Harris’ “I’ve never been very good at leaving things behind. I tried, but I have always left fragments of myself there too, like seeds awaiting their chance to grow” and turned them into a concrete poetry installed in the shape and form of a house’s plan. The quote symbolizes how the definition of ‘home’ is drawn and somewhat constrained. The more obvious changes took place during the second phase when the artist began arranging the structure of wooden walls and a wheeled aluminum structure. It was as if the poetry on the wall extended its physicality into the space of the room. The wheels allow the boundary of a home to be freely moved, while undeniably diminishing the ability to define the space as a result.

While there are other interesting works from other artists that are not mentioned in this article, what we are able to gather from the exhibition is how the obscurity (mentioned earlier) surrounding the exhibition isn’t always expressed in a negative tone. One of the reasons is perhaps the state of obscurity usually and inevitably ensues when one enters the unfamiliar territory. What’s challenging and discernible about the ‘obscurity’ is perhaps the fact that it can still be controlled, allowing the artworks to vigorously tell their stories as the definition of art is being expanded farther and broader.