CHOMCHON FUSINPAIBOON EXPLORES HOW THAILAND’S NATIONAL IDENTITY IN ARTS AND THE COUNTRY’S MODERNIZATION IN INDUSTRY AND ECONOMY INFLUENCE THE DESIGN OF THAI PAVILIONS AT INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITIONS IN THE 1930S WHICH RAISES THE QUESTION OF WHAT HAS BEEN CHANGED IN 2021

TEXT: CHOMCHON FUSINPAIBOON

PHOTO CREDITS AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

In a lecture broadcast in 1935, later published in 1937, and again partly in 1952, Phra Phromphichit, a prominent master builder of the Department of Fine Arts, pointed out the significance of national arts. He argued about the significance of national identity in arts that was intended to allow not only Thais to give recognition to their ancestors but westerners to recognise and identify the Thais in their present state. This article examines how this idea influenced the designs of Thai pavilions at international expositions in the 1930s in relation to the country’s modernisation in industry and economy. It also discusses how the idea transformed the meaning and roles of national arts.

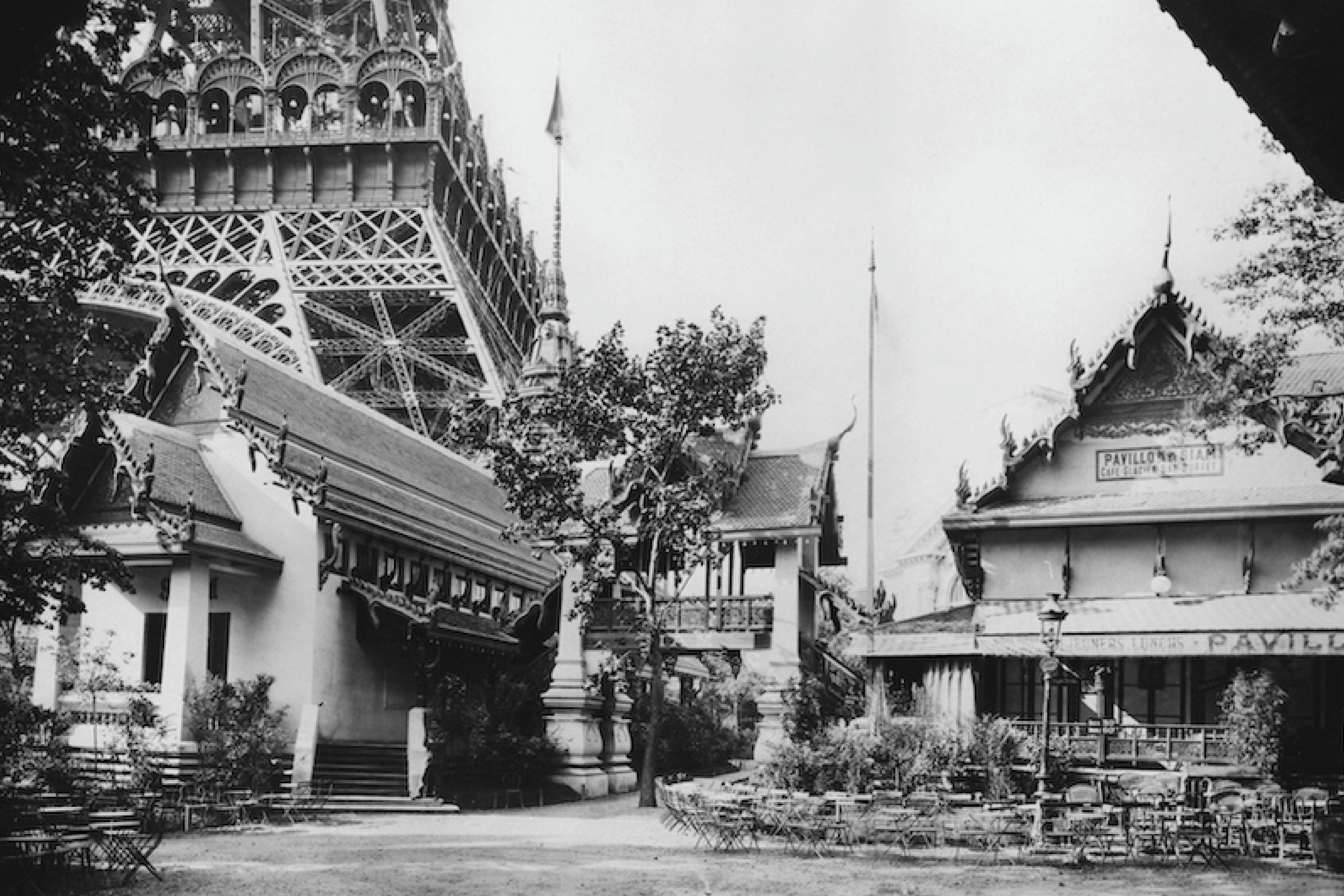

Before 1932, Siam had participated in a number of international expositions, starting semi-officially with the Great London Exposition of 1862, and it then officially entered the Expositions Universelles in Paris of 1867 and 1878. Across the Atlantic, Siam also participated in the Centennial Exposition Philadelphia in 1876 and Columbia Exposition 1893 in Chicago respectively. The Exposition Universelles in Paris 1900 was the first year that Siam had its own pavilion for its exhibition. In Esposizione Internationale in Turin of 1911, Siam participated in the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the unification of modern Italy with a Siamese pavilion, stood elegantly on the right bank of the River Po.

Siamese Pavilion at Paris Exposition Universelles of 1900 | Photo: Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau

A perspective drawing and the Beaux-arts-based plan of the Siamese pavilion at Torino Esposizione Internationale 1911 | Photo: G. E. Gerini, Siam and Its Productions, Arts and Manufactures: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Siamese Section at the International Exhibition of Industry and Labour Held in Turin, April 29-November 19, 1911 (Hertford: Stephen Austin, 1912), p. inner front cover.

The economic depressions during the late-1920s and early-1930s led the Siamese Government to reject many invitations from international expositions until 1935. The fact that the expositions were normally categorised as trade fairs set them under the responsibility of the Ministry of Commerce (Krasuang Setthakan). However, the newly established Department of Fine Arts was from this time on responsible for the design of Siamese Pavilions.

Returning to Phra Phromphichit’s claim about the government’s policy to incorporate Thai character in important buildings in order to exhibit the nation’s identity and competence and as recognised evidence of its continuous development, he started to implement it by designing a Siamese pavilion for Yokohama Exhibition of 1935, in which natural and artistic goods were sent to be exhibited. Parts of the building were executed in Bangkok and sent to be assembled in Japan under the supervision of the Department of Fine Arts’s craftsmen. Phra Phromphichit was confident that Thai art could be proudly exhibited on international stages, and that foreigners who came to travel in Siam wanted to see such art — all of this would help assure them that ‘Siam was not a barbaric country’.

Even though its value was well recognised by the government, the costly expression of the national identity was not always easy to implement due to economic constraints. Also in 1935, the government initially rejected the invitation to participate in the Pan Pacific Peace Exhibition of 1937 in Nagoya, stating that the main export products, i.e. rice, tin, timber, had found markets, while other produces such as pepper, leather, and horns were not of controllable quality. This reiterates the circumstance of Siam that export depended on a limited number of products due to the lack of advanced technology and funding to develop other products to an adequate standard. Considering this alongside the on-going, yet far from smooth, development in fields such as industry, healthcare, education, and the army, the age-old national arts were no doubt something Siamese scholars and elite, no matter whether under the old or the new regime, should be proud of and promote, as they were something hardly to be found in any other comparable country.

The invitation in 1935 to participate in the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris of 1937 was also initially rejected by the Ministry of Commerce, due to continuing economic difficulties. However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs petitioned the decision stating that Siam’s dignity as an independent Asian state was to be undermined by absence from this exposition. As a result of the appeal, the government decided to participate.

The theme of the exposition this year was ‘Arts and Techniques in Modern Life’. The Siamese government sent Phra Sarot Rattananimman (Sarot Sukkhayang), the Head of Architecture Division in the Fine Arts Department, to visit the exhibition and also to ‘study Sathapattayakam Baeb Maimai (new styles of architecture) to benefit the government’s work’.

Sukkhayang later published an article in Silpakorn Journal. He dismissed the design of Japanese Pavilion that had received the Grand Prix prize alongside Jose Louis Sert’s Spanish Pavilion and Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion. The Japanese Pavilion was the first execution from a so-called oriental country that broke away from the usual expression of tradition in architecture. Like Siam, Japan had since 1873 constructed pavilions following traditional models. Like Siam too, before 1937, Japan had been basically concerned about what the international audience might have expected to see, while in Paris 1937, when Japanese architects became confident with their country’s modernity and power, it finally started to propose what it wanted the audience to see, instead of what it was expected. Its architect responded explicitly to the theme of ‘modern life’, using Le Corbusier’s five points of modern architecture for its design principle.

Japanese Pavilion by Junzo Sakakura at Paris Exposition 1937 | Photo: Reyner Banham, ‘The Japonization of World Architecture’ in Contemporary Architecture of Japan 1958–1984, ed. by Hiroyuki Suzuki (New York: Rizzoli, 1985), pp. 16–27 (17).

On the other hand, under the same exposition’s overall theme of ‘modern life’, the Siamese pavilion was originally designed by Phra Phromphichit to have a main Sala (Thai pavilion) at the centre, modeled after Aisawan Thipphaya-at royal pavilion at Bang Pa-in Palace, and Param (a traditional form of pavilion with flat roof) at four corners. The spaces inside exhibited traditional arts such as niello ware, lacquer ware, mother of pearl ware, gems, photographs, paintings, music instruments, Khon masks, cast and sculpted Buddha images, and natural produces like rice, lace, tin, etc. The design was to be reassembled at the venue. Under the supervision of the architect M. C. Samaichaloem Kridakorn on site. The design was revised as a Sala sitting on a high base, in which the exhibition was held.

The exhibition space had a main hall at the centre. In the hall, the plain structure was lined with friezes seemingly inspired by a Siamese pattern. The capitals could have been perceived as a western element. These designs could have been seen as an interpretation of Thai architecture and art to suit modern function, building type, and technology, itself a hybrid product of progress and Thai identity. But a more-critically hybrid feature lay in the middle of the hall. There was located a podium with the head of a Buddha’s image on top. It was not even a bust, but a head. Another similar head of the Buddha image was also exhibited in another room among other stuff, such as herbs, play masks, and a portrait of the Queen.

Exhibiting a head of Buddha was unusual in Buddhist monasteries in Siam, but perhaps not uncommon in museums of advanced countries. The use of the Buddha’s head here was definitely in the latter sense. It served no purpose of worship but of exhibition. On one hand, the image was considered as an artefact, an archaeological object exhibiting Siam’s character and competence in the artistic field. On the other hand, it was an exotic stuff for foreigners who might admire its exotic quality but saw little relevance to their daily modern life.

Siamese Pavilion as built at Paris Exposition of 1937 | Photo: Funeral Book of M.C.Samaichaloem Kridakorn

The exhibition of the Siamese Pavilion including the head of a Buddha in the centre of the main hall | Photo: Funeral Book of M.C.Samaichaloem Kridakorn

Siam’s modern authority stuck with their belief in exhibiting tradition, and some natural produces, rather than modern products that had yet to achieve an admirable standard. The Gold Medal and certificate (Diplome d’ Honneur) for aesthetics awarded to it was perhaps enough to convince the Siamese authority that what it had done was in an appropriate direction.

After this experience in Paris, the government accepted the invitation from the New York World’s Fair 1939 as it had by now come up with tourism as one of new economic activities. Sticking to the emphasis on the exhibition of traditional artworks, the report after the exhibition concluded that the major aim of the exhibitions abroad was not to sell the products exhibited, as they were not the main export goods, but to promote Thailand and to draw tourists to the country.

The Thai authority expected Thai arts to be admired but not necessarily to sell. The so-called traditional arts became a static heritage, not much needed, if at all, to be developed to get along with the changing society. As a result, some heritage items were transported to be exhibited abroad to draw tourists to the country to appreciate the rest of the heritage, presented as exotic objects irrelevant to their modern society. The static heritage only sat there to convince Thai society that they were on par with the West when considering their glorious past and culture exhibited through refined artifacts, despite the fact that they had also been trying to catch up with the West and now also Japan in terms of development and prosperity for some time, yet were hardly successful.

This article demonstrates how the designs of Thailand’s pavilions in international expositions before World War II were entangled with global politics and economy, involving the questions of Thailand’s position and competitiveness in the world stage. It shows how the designs of these pavilions not only had to deal with the country’s struggling in economic development but also to help the Thai state, and its elite, to use traditional culture to cope with that situation. They wanted to exhibit delicate crafts from the past because they were not confident yet about the quality of their modern stuffs. This direction transformed Thais’ views towards their own traditional culture.

What have been seen during the 1930s, such as exhibiting exotic culture instead of advanced products of international standard, and showing refined artifacts to draw tourists, still appear to be what Thai governments direct the design of Thailand’s Pavilions in Expos in the 21st century. It may be more than timely now to question whether this direction persists because Thailand’s advanced products do not meet international standard. Or even whether the fact that this direction has persisted for quite a while has affected the governments’ supports to develop advanced products. At the same time, it is also worth asking whether Thais’ views towards their own traditional culture have been too static for some time and need more transformation. Most importantly, how can architecture and the architectural profession be part of the transformation or reinvention of not only Thai traditional culture, but also Thailand?

Edited from Fusinpaiboon, Chomchon. “Modernisation of Building : The Transplantation of the Concept of Architecture from Europe to Thailand, 1930-1950s,” PhD Dissertation, University of Sheffield, January 1, 2014, pp.516-553. Full references are in the dissertation via link