BANGKOK ART AND CULTURE CENTRE (BACC) HOLDS THE 7TH EARLY YEARS PROJECT EXHIBITION WHERE SEVERAL PROMISING ARTISTS SHOWCASE OUTSTANDING ARTWORKS REFLECTING THEIR VIEWS ON MODERN THAI SOCIETY

TEXT: TUNYAPORN HONGTONG

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

The Early Years Project #7: A Paradigm Shift is an exhibition imbued with the younger generation’s distinct ‘energy’. Such vibrancy is rooted in a fresh approach to perspective, thought, and presentation, refraining from undue preoccupation with extraneous factors. It’s the type of characteristic that is often found in the early works of artists at the onset of their careers. As these artists mature and amass experiences, their thought processes evolve, becoming more profound, sophisticated and more nuanced, influenced by an array of elements integral to their artistic creation.

This edition showcases the works of eight emerging artists, carefully selected and developed through the Early Years Project. Launched and overseen by the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC), the project aims to foster and support the burgeoning talent of new artists. Reflecting on the project’s seven-year history of continuous effort, we have witnessed several participants from previous iterations of Early Years currently making remarkable strides in the art world.

The latest installment of the Early Years Project presents several compelling pieces, although here we will spotlight a select few, emphasizing those with the potential to resonate widely with audiences. These selected works are particularly notable for their engagement with social themes.

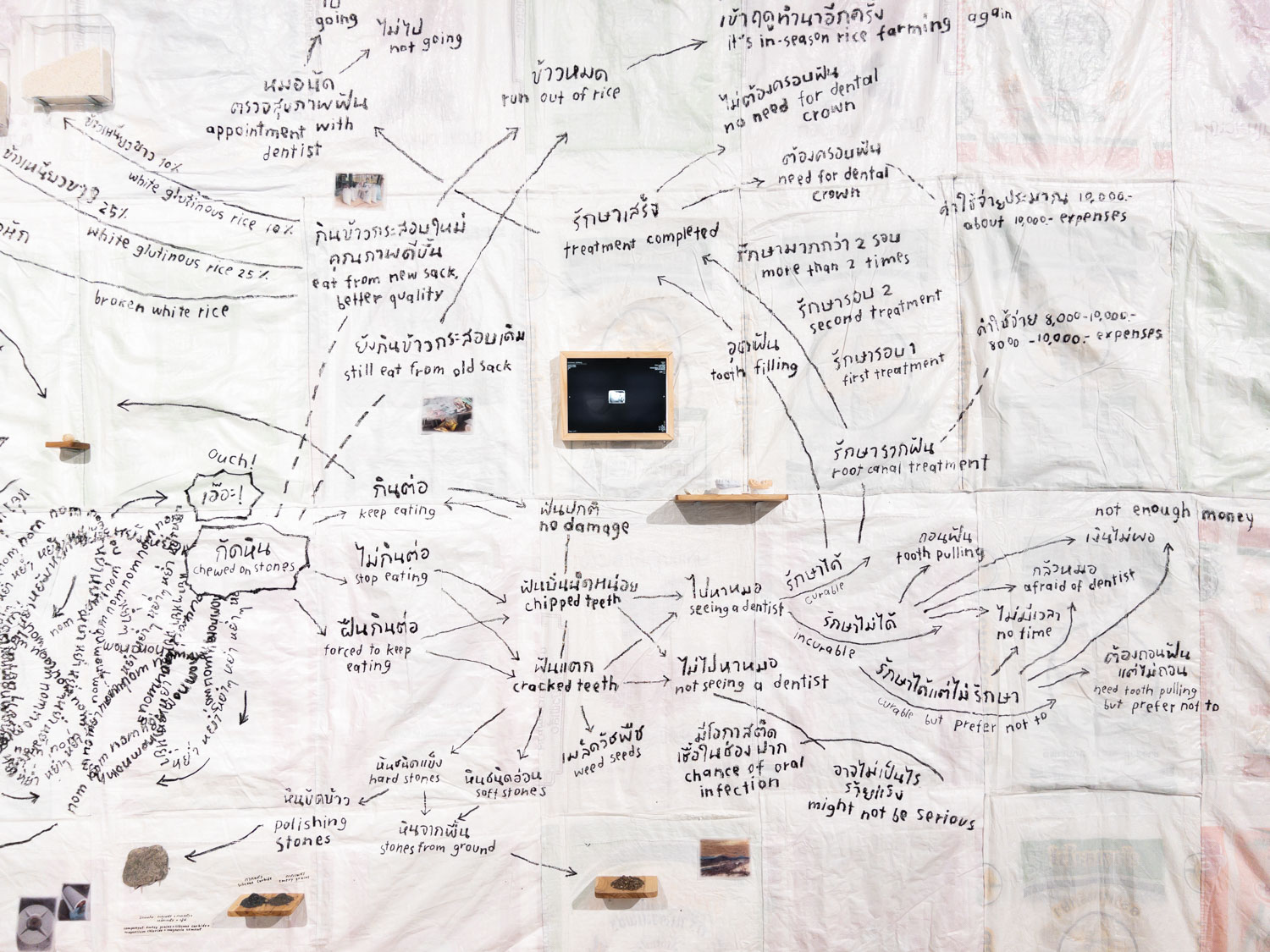

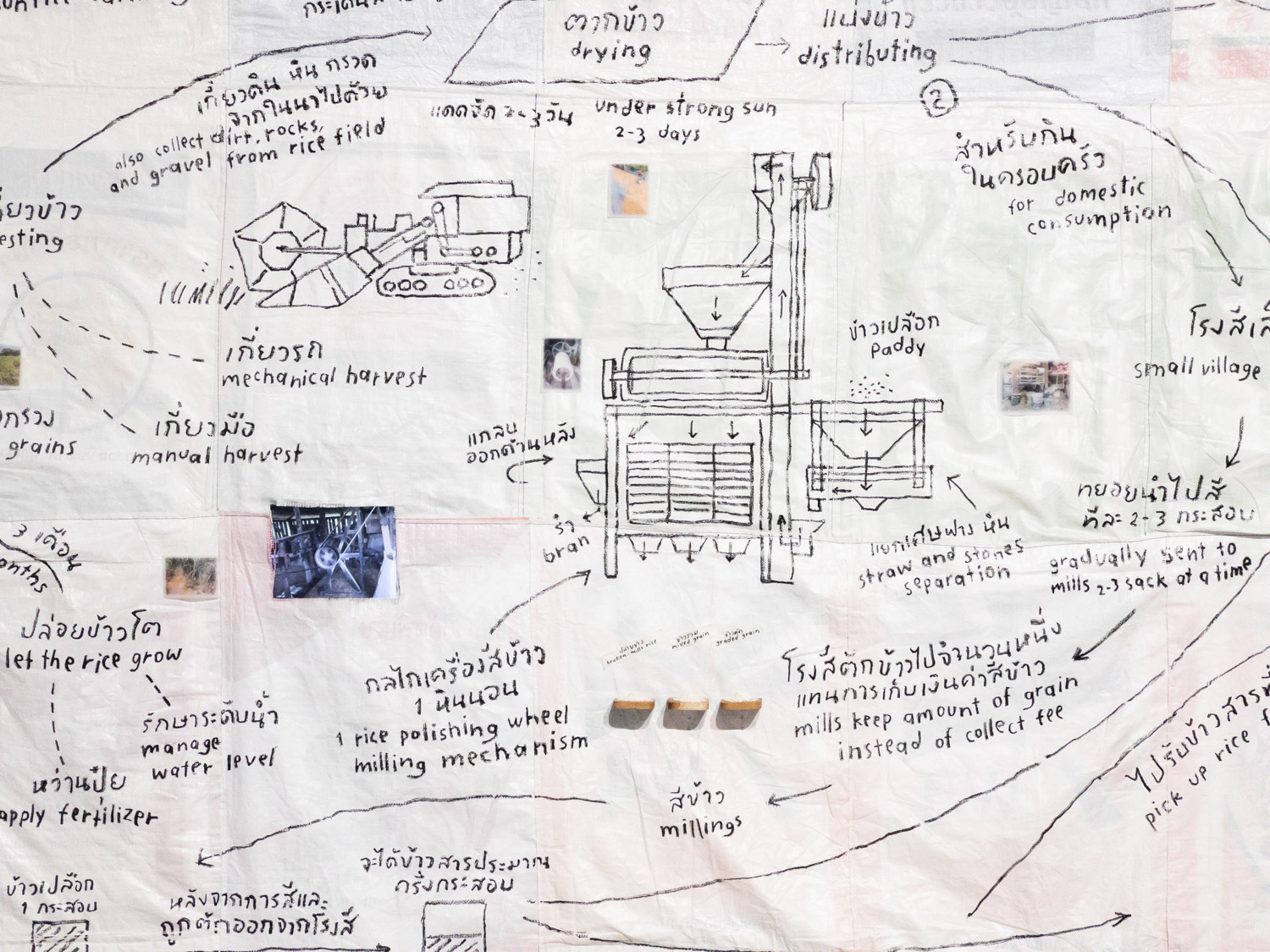

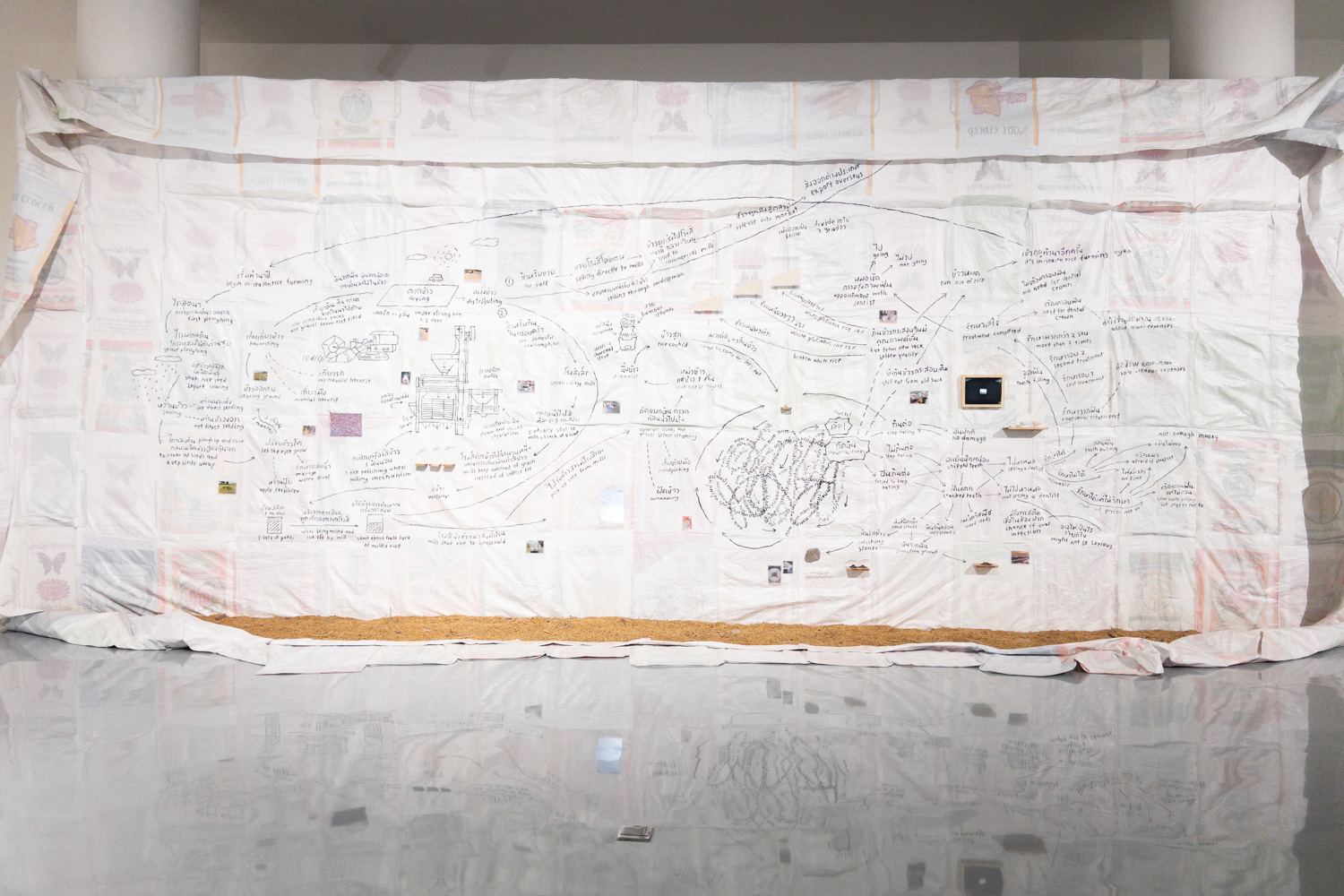

Beginning with Kanokwan Sutthang and her piece ‘Road of Rocks in Rice’ (2023), this work is sparked by the artist’s fascination with something as apparently trivial as the gravel she frequently encountered in the rice her family consumed while she resided in Ubon Ratchathani, a province in the northeastern region of Thailand. Her family of rice farmers always reserves a part of their yield for their own household consumption. Kanokwan, through a diagram meticulously drawn by hand on rice sacks sewn together, delineates the rice production process. This illustration posits that rocks could become intermixed with the rice during the harvesting, drying, and milling stages. Despite diligent efforts to eliminate these stones prior to cooking, eradicating them completely proved unattainable, often leading to the unpleasant experience of biting into gravel. This sometimes resulted in chipped or even cracked teeth, a problem she never encountered with the “Bangkok rice” after relocating to the capital city.

‘Road of Rocks in Rice’ by Kanokwan is both playful and perceptive. Her sense of humor is evident in her narrative conveyed through the diagram, particularly when she describes the ordeal of chewing on rocks in rice: “Some continue to eat, some do so reluctantly, and break a tooth.” She goes on to detail, “Some seek dental care, some do not; some are treatable, some are not—or some could seek treatment but opt not to,” citing various reasons such as “no time, fear of dentists, lack of money, etc.” Yet, this seemingly minor story of encountering rocks in rice and its whimsical delivery reveals a deeper societal commentary. It underscores the dramatic disparity in life quality between city dwellers and those in rural areas, especially emphasizing the irony that the very farmers who produce the rice often end up with a lower quality product, leading to dental health issues and the consequent financial strain that comes with the expensive treatments.

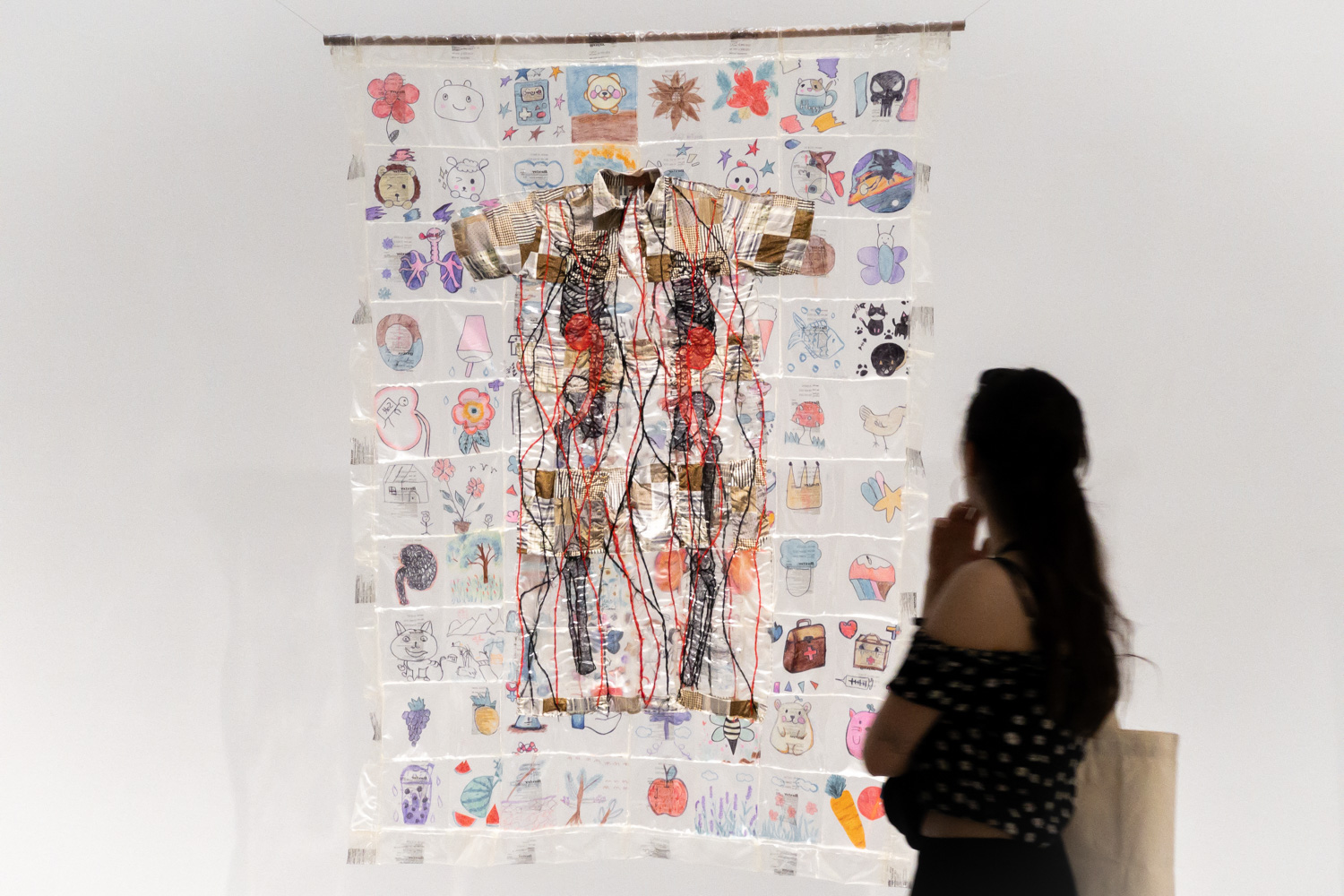

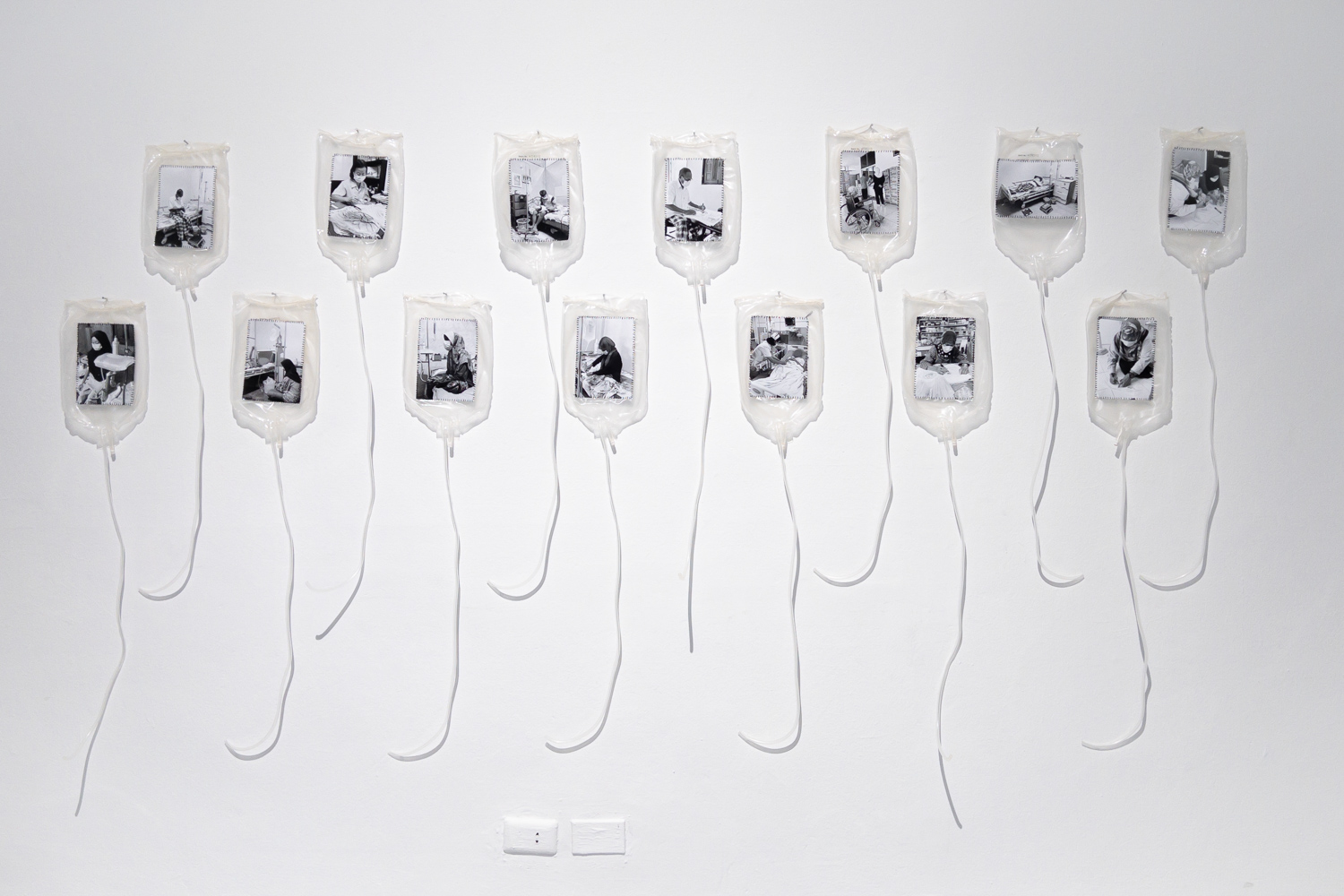

‘Memory of Life’ (2023) by Nordiana Beehing bears a resemblance to ‘Road of Rocks in Rice’ as it also stems from the artist’s personal experiences and broadens to address societal ramifications. However, in contrast to Kanokwan’s use of humor and satire, Nordiana adopts a more solemn tone, a choice likely influenced by her four-year ordeal of navigating hospital visits to care for her father, a kidney disease patient. This harrowing journey introduced her to the widespread stress that afflicts patients and their families and caretakers, a distress she encountered throughout her frequent visits to a government hospital.

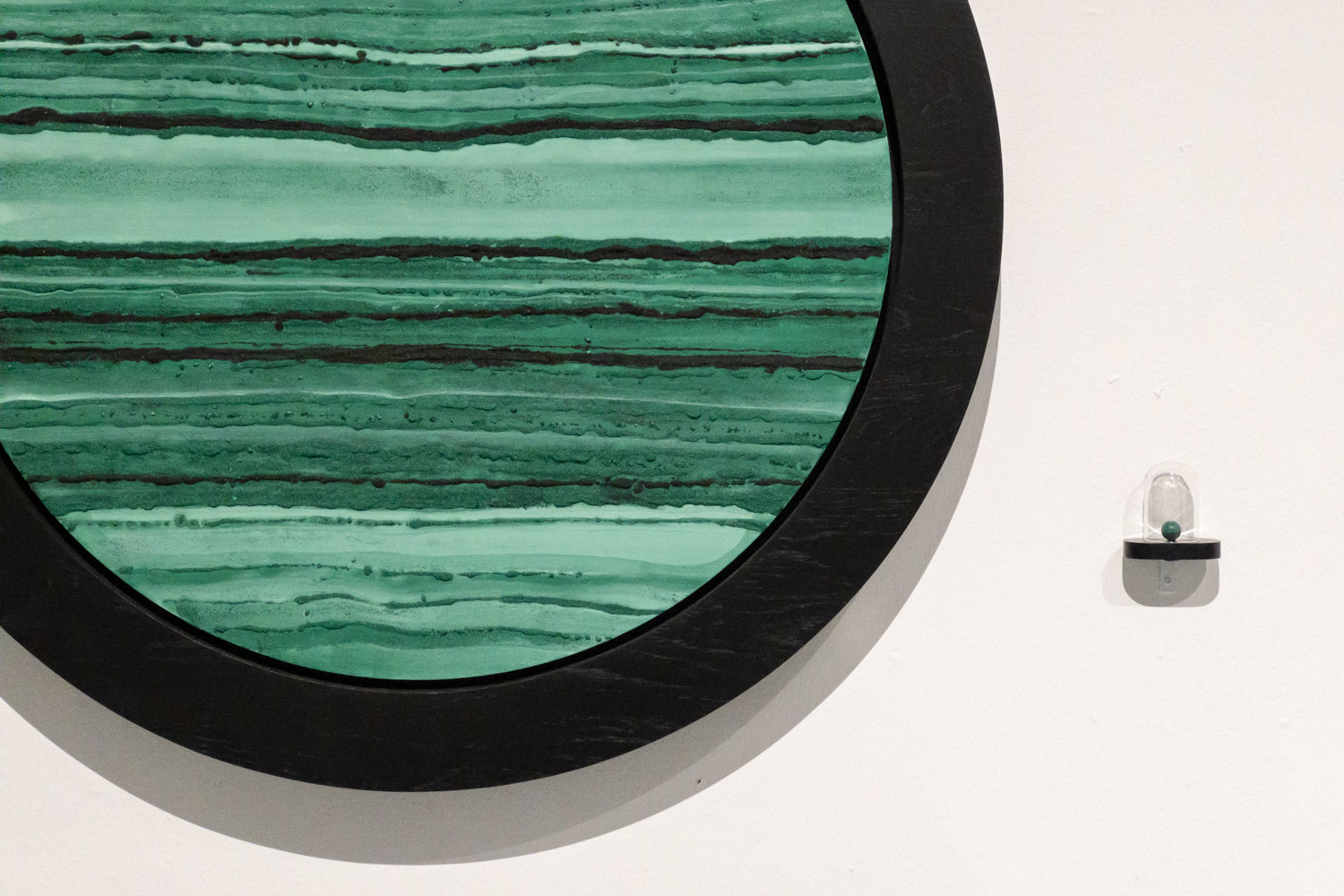

Motivated by this firsthand experience, Nordiana initiated the ‘Safe Zone’ project, which extended an invitation to patients and their families to engage in activities that fostered emotional expression and creativity through painting on used dialysis solution bags. After being cleaned, these bags were stitched together to form expansive canvases. The project showcased not only the participants’ drawings but also embroidered pieces created by the artist to convey the emotions and life stories she experienced while being at a government hospital in the Betong district of Yala province.

In my opinion, the eclectic mix of the eight artists selected proves to be the right combination. Some of their works are exploratory, focusing on experimenting with artistic techniques and formats, while others, including the aforementioned examples, deeply and interestingly engage with social themes. This diverse array ensures the exhibition’s broad appeal. While the former category might capture the interest of visual arts enthusiasts, the latter, accessible without requiring an artistic background, resonates with societal narratives that touch us all.

Furthermore, the social themes explored in each piece vary widely, reflecting the diverse backgrounds of the eight artists. This group includes individuals from the Bangkok metropolitan area, an artist born and raised in Ubon Ratchathani who is now working in Bangkok, and artists from provinces such as Chonburi, Yala, Suphanburi, and Chiang Mai. The latter is essentially a mix of a rural province, a large city, and a tourist destination. Notably, Chiang Mai is represented by two artists from the Faculty of Fine Arts at Chiang Mai University, both selected for this year’s Early Years.

Jakkrapan Sriwichai, one of the two highlighted artists, addressed the subject of the Chiang Mai light rail transit train through his sculpture ‘Invisible Train’ (2023). This piece is constructed from stainless steel clothes racks, assembled with four rubber wheels and office chairs, topped with overhead stainless-steel rings that mimic those found in electric trains. The concept of ‘invisibility’ in Jakkrapan’s work is derived from the Chiang Mai light rail project, which has been in the planning phase for over two decades. This project has ignited debates surrounding its potential advantages and disadvantages, particularly its effects on the city’s historic architecture, the lifestyle of its community, and the environment. Despite extensive discussions, Chiang Mai’s residents are yet to see the light rail system come to fruition.

Alongside the sculpture featured in the exhibition, four video installations depict Jakkrapan and his friends maneuvering the sculpture along various paths that are projected to form part of the Chiang Mai light rail network. This peculiar disruption into public spaces is intended to stimulate community discussions regarding the mass transit project. Additionally, another video installation offers a simulation of the view a passenger might enjoy from a light rail train, complemented by an announcement designed to encourage viewers’ deeper contemplation, such as ‘Please mind the gap between hope and concern.’

Among the eight artists featured, Vacharanont Sinvaravatn‘s work is likely the most recognizable to those familiar with Thailand’s contemporary art scene, especially following his solo exhibition ‘The Boundary of Solitude’ at the SAC Gallery last year. Consequently, my experience of Vacharanont’s art differs from that with other Early Years participants. Instead of an introduction, viewing his work here feels more like a continuation of his artistic journey.

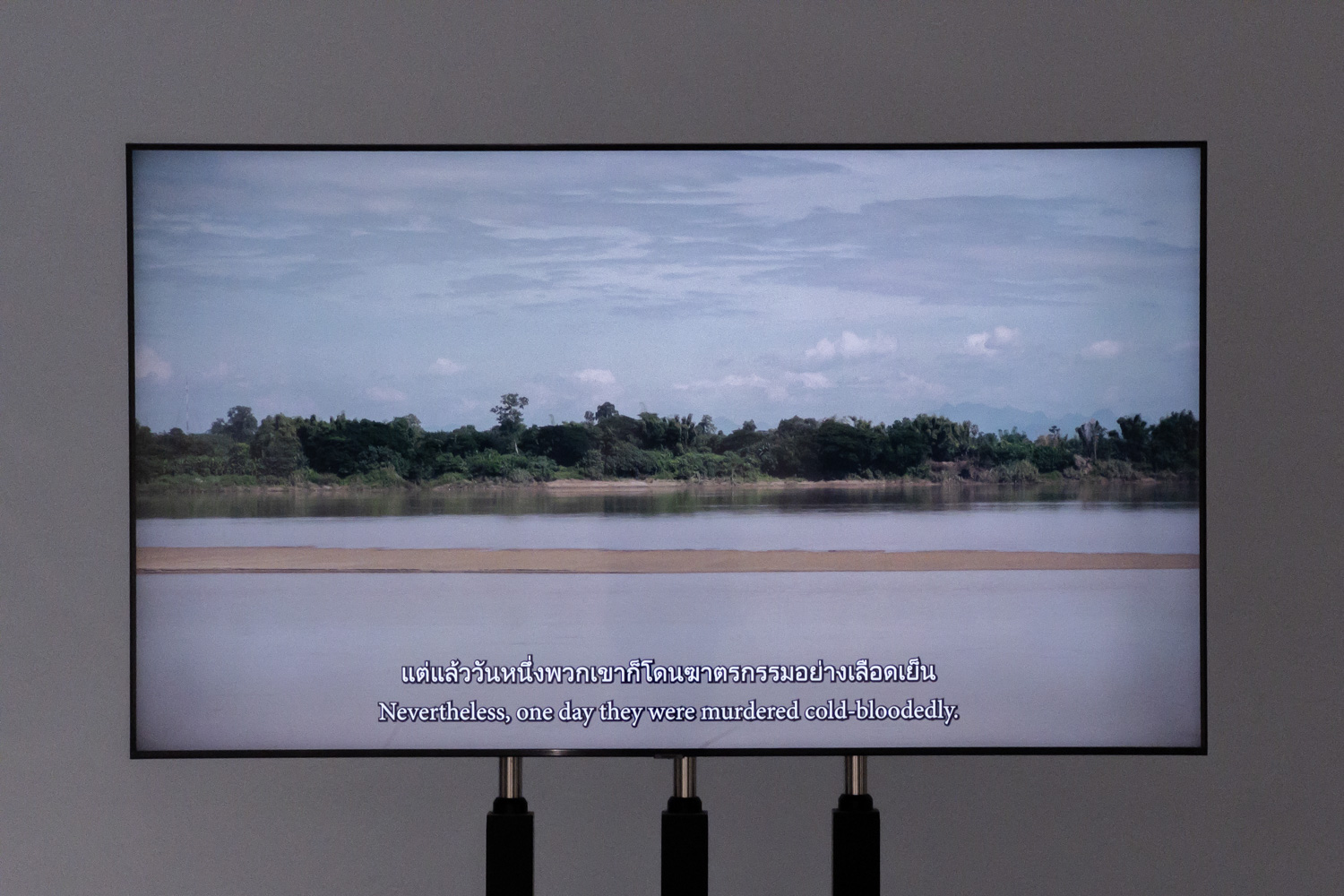

Vacharanont’s video installation ‘May this land bear witness’ (2024) captivates with a backdrop featuring a landscape photograph of snow-capped mountains mirrored in water, immediately seizing the viewer’s attention with its surreal beauty. Upon closer examination, viewers find two essay films that navigate the realms of reality and fiction. The two films portray landscapes. One film tells a story deeply rooted in Thai society—the belief in the Thai people’s origin from the Altai Mountains (detailing the challenges Thais would have faced had they truly embarked on such a migration), while the other delves into contemporary Thai social and political landscapes.

Vacharanont’s art, like that of a few other artists in this year’s Early Years, is driven by a fascination with a specific artistic form: rural landscapes. In an interview with art4d magazine, he expressed his curiosity about the interaction between landscapes and our perceptions and thoughts, pondering why individuals unfamiliar with rural life can intuitively depict it and why many idealize the countryside as a utopia. His exploration and experimentation with landscapes invite us to scrutinize our beliefs and assumptions, potentially molded by societal factors, some recognized and others unnoticed.

This year’s Early Years project emerges as yet another intriguing endeavor. Having reviewed all the works, I eagerly anticipate and hope to see these artists continue to grow and establish their names in the art world in the future.

The Early Years Project #7: A change In the paradigm exhibition was held from Jan 10th – May 12th 2024 at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, 7th floor.