AS THE PAST NEVER FADES AND THE FUTURE REMAINS UNCERTAIN, THASNAI USES ART TO QUESTION THE LINGERING AUTHORITARIANISM OF POST-WAR TIMES IN THE EXHIBITION ‘TOXIC REMAINS: PARASITES OF A BETRAYED DREAM’

TEXT: PRAT TINRAT

PHOTO: PREECHA PATTARA-UMPORNCHAI EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

A Dream That Persists Through the Toxic Wreckage of History.

“The Cold War may have ended in Europe, but in Southeast Asia, it has never truly ended.”

The quiet yet searing observation of Thasnai Sethaseree, drawn from lived experience, forms the conceptual backbone of his exhibition ‘Toxic Remains: Parasites of a Betrayed Dream.’ More than a reckoning with political memory, the work unearths the lingering ‘residues of authoritarianism,’ embedded not only in historical narratives but in the very fabric of emotion, belief, and collective spirit. Political events long presumed to be over are, in truth, continually reproduced, layered, re-scripted, and reintroduced under new façades. They return cloaked in the rhetoric of ‘virtue’ and ‘righteousness,’ weaponized as instruments of governance to claim and reclaim moral authority.

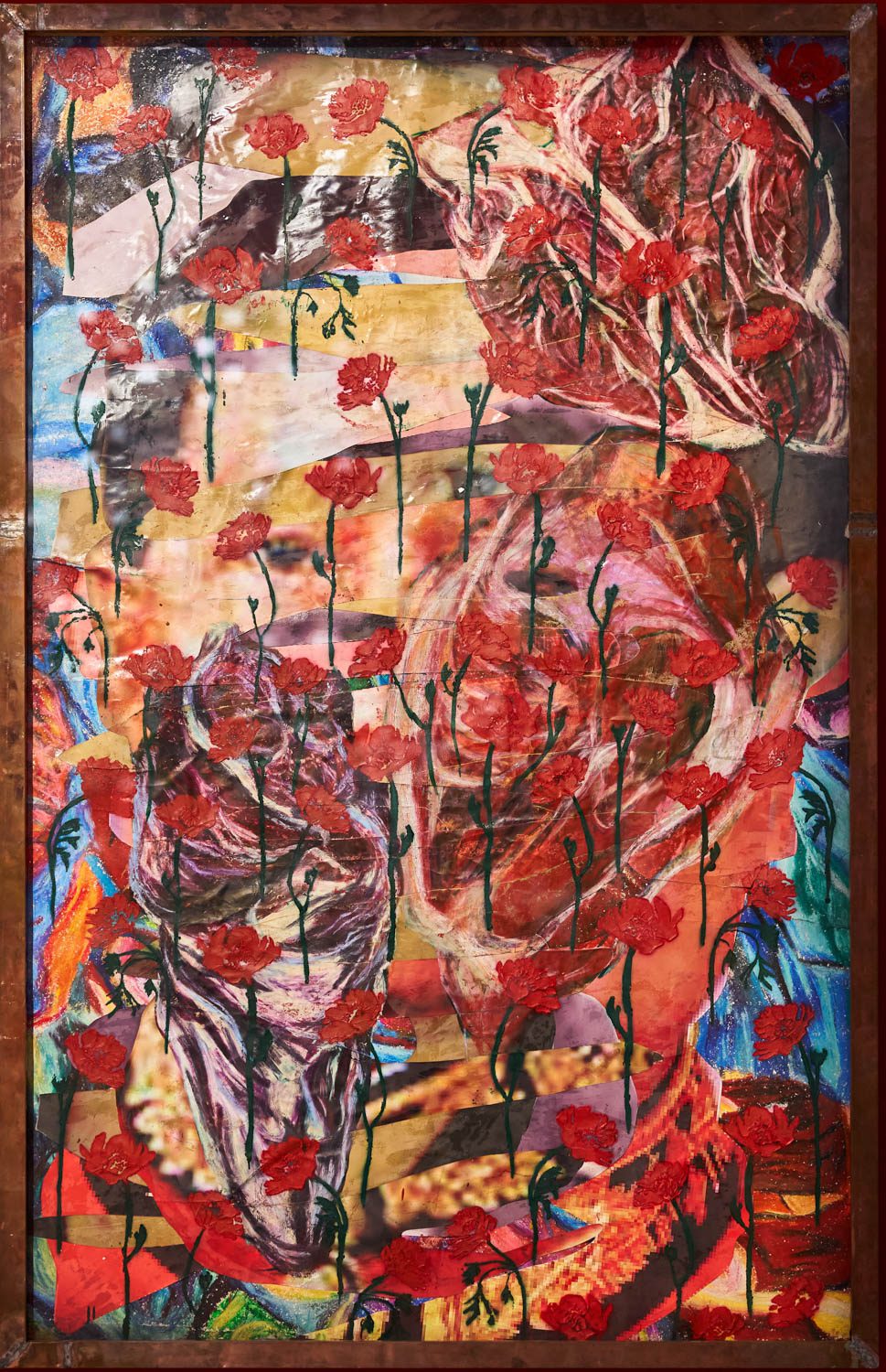

In the exhibition space, a sprawling collage fuses pixelated portraits of uniformed leaders, dissected female bodies, and carnivorous blooms into a volatile visual terrain—an unsettled landscape where the past refuses stillness and the future remains without a secure footing. Within this field of toxic remnants, Thasnai positions art as both a site of critical resistance and a fragile sanctuary for hope. However faint that hope may be, it lingers just enough to compel the question: Do the dreams and hopes that survive still have a place we can believe in?

The Artist’s Path: From Conceptual Art to Quiet Resistance

Before 2014, Thasnai Sethaseree’s practice was rooted in the language of Conceptual Art; site-specific works that existed in dialogue with their immediate context in time and place. For him, art was an experiment, a provocation, a staged encounter designed to spark confrontation, only to be dismantled once the exhibition closed. What remained were not objects, but thoughts, conversations, and the ripples of response carried forward by those who had engaged with the work.

The 2014 military coup in Thailand marked a turning point. When inquiry itself became an object of surveillance, Thasnai found that he could no longer remain a detached observer. The pressures he faced were no longer symbolic but physical: letters tracking his movements, covert monitoring, and photographic documentation. Retreating from the public arena, he withdrew to his studio in Chiang Mai. There, his practice began to shift quietly, from constructing ephemeral, event-based spaces to collecting, recording, and painstakingly assembling fragments lodged in memory. For Thasnai, collage became more than a technique; it evolved into a process, a discipline of piecing together remnants into coherence.

His approach to collage; cutting and pasting, does not rest solely on the foundations of Western art history. It draws equally from the vernacular visual traditions of Northern and Northeastern Thailand: ceremonial decorations such as ‘tung’ (ritual flags), folded paper ornaments, and suspended paper cuttings used in merit-making festivals, annual celebrations, and funerals. These layered forms carry with them belief systems, memories, and uncertainties, fleeting in their material presence, yet capable of leaving an imprint far more enduring than any permanent monument.

The Power of Innocence: How a Son’s Influence Shapes a Vision of the Future

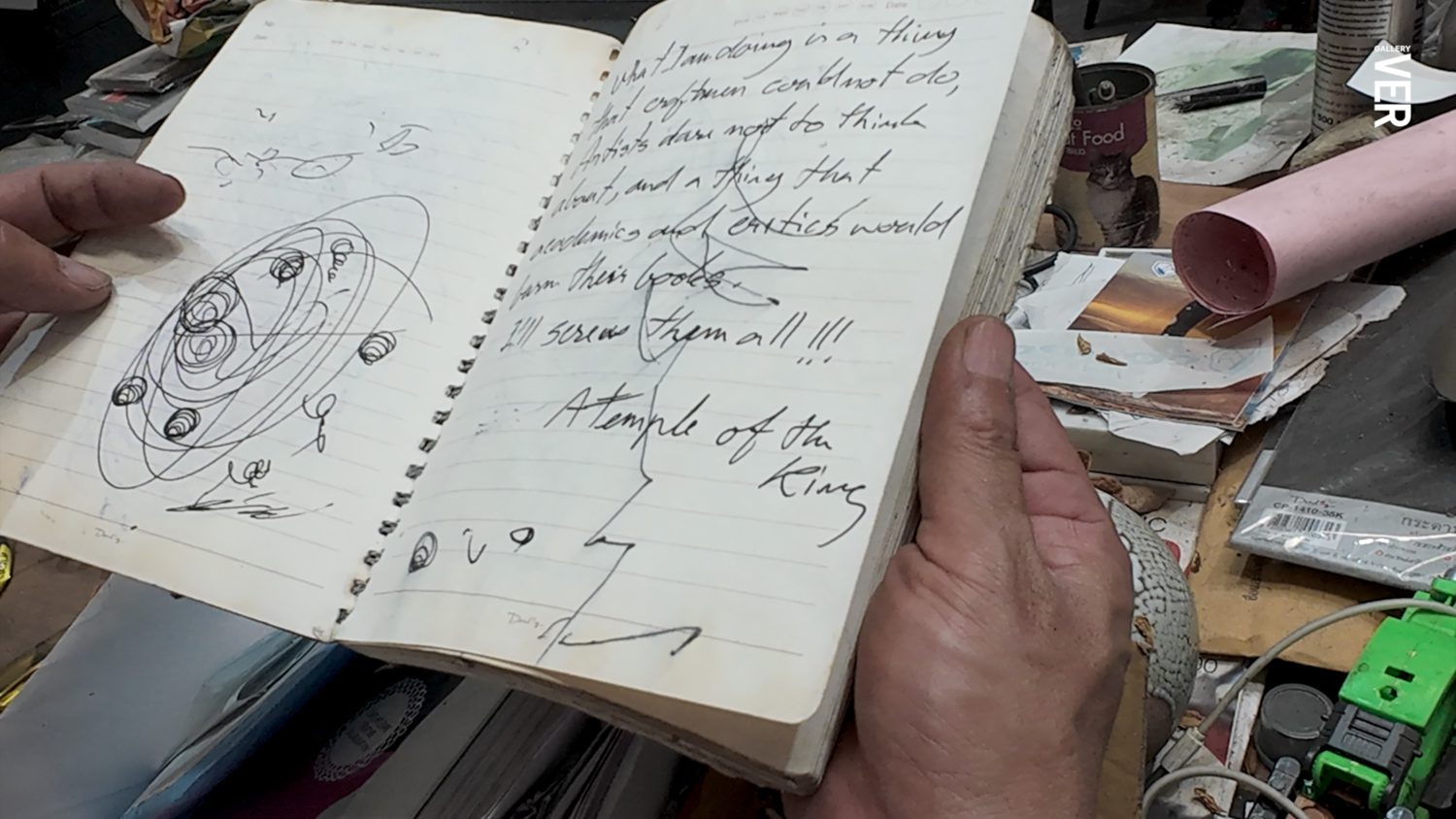

During his period of retreat in the studio with his young son, Thasnai began noticing a quiet, persistent act: the boy would draw over and over in his father’s sketchbook, indifferent to the marks that were already there. These unrestrained lines, layered one atop another, began to form an accidental stratum of thought, feeling, and chance. The process echoed, in spirit, the logic of Thasnai’s own collage practice.

The son’s lines in Professor Thasnai’s sketchbook | Photo courtesy of Gallery VER and the artist, Thasanai Sethaseree

Cold War: The Mysterious at MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, 2022 | Photo courtesy of Gallery VER and the artist, Thasanai Sethaseree

He later enlarged these lines to monumental scale, integrating them into Cold War: The Mysterious, an exhibition staged at MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, in 2022. What began as traces of innocence transformed into a raw, almost combative force; an energy in the process of being learned, channeled, and wielded, with no awareness of its impact in the adult world. The influence shaping his post-2014 work, then, stems not solely from political experience, but also from the intimacy of life alongside his son: witnessing a child’s dreams, untampered freedom, and innocence unshaped by the systems of control. This innocence, for Thasnai, stands not for one child alone, but for an entire world they will one day share with others. His art, therefore, is no longer only an act of revisiting the past. It is also an urgent question: What kind of society are we allowing to take shape, and which aspects of it must we stand up to challenge?

Behind the Lines: Intellectual Foundations Shaped by Family and Learning

Thasnai’s foundations were never confined to a single lineage of thought, but rather grew from a tapestry of influences. They’re seemingly at odds, yet coexisting in harmony. His paternal grandfather was a Christian minister; his maternal grandfather, a Buddhist monk. He was raised with both the Bible and Buddhist scriptures, alongside strands of Eastern and Western philosophy that alternated as the backdrop to his lifelong questioning. Adding another layer, his father worked in politics, surrounding the household with political documents, ideological treatises, historical accounts, and texts on governance. Together, these formed a rich internal archive; an intellectual reservoir that continues to shape the conceptual depth of his work.

The Tower of Bubbles at Gwangju | Photo courtesy of Gallery VER and the artist, Thasanai Sethaseree

The Tower of Bubbles at Gwangju | Photo courtesy of Gallery VER and the artist, Thasanai Sethaseree

In ‘Tower of Bubble,’ presented at an art festival in Gwangju—a city marked indelibly by the Gwangju Uprising of May 1980, a pivotal pro-democracy movement—Thasnai drew inspiration from the biblical story of the Tower of Babel. In this tale, humanity joins forces to construct a tower reaching the heavens, an act of defiance that prompts God to fracture their shared language into many, scattering them and leaving the tower unfinished. For Thasnai, the tower carries multiple resonances: as a religious symbol, and as an emblem that was later appropriated in Russian political discourse in 2022.

The origins of this work emerged from an intimate moment: while bathing with his young son, Thasnai noticed a quiet contrast. As an adult, he moved quickly to wash and rinse, while the child lingered, playing with the soap bubbles, lost in dreams and imagination. ‘Tower of Bubble’ became, for him, an emblem of innocent defiance, too pure for the realities of the world, and too fragile to endure for long. In Thasnai’s view, this fragility mirrors a recurring pattern in history. Though the contexts may shift, the contours of power and resistance seem to circle back in familiar rhythms, never fully disappearing even after the Cold War had ostensibly ended.

The Human Impulse to Prove Oneself Right: The Discourse of ‘Virtue’ and the Toxic Remains of the Cold War

For the Western world, the Cold War seemed to draw to a close in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Southeast Asia, however, its toxic legacy remains remain deeply embedded in the structures of power, manifesting in varied forms, from state policies and the promotion of extreme nationalism to beauty pageants and beyond. Yet one of its most insidious legacies is rarely addressed: the ongoing contest for moral authority. Here, the discourse of ‘virtue’ is deployed as a political instrument, crafted to divide, to draw stark lines between sides, and to operate as a ‘technology of governance’ that needs no physical force, exerting control instead through language, belief, and fear.

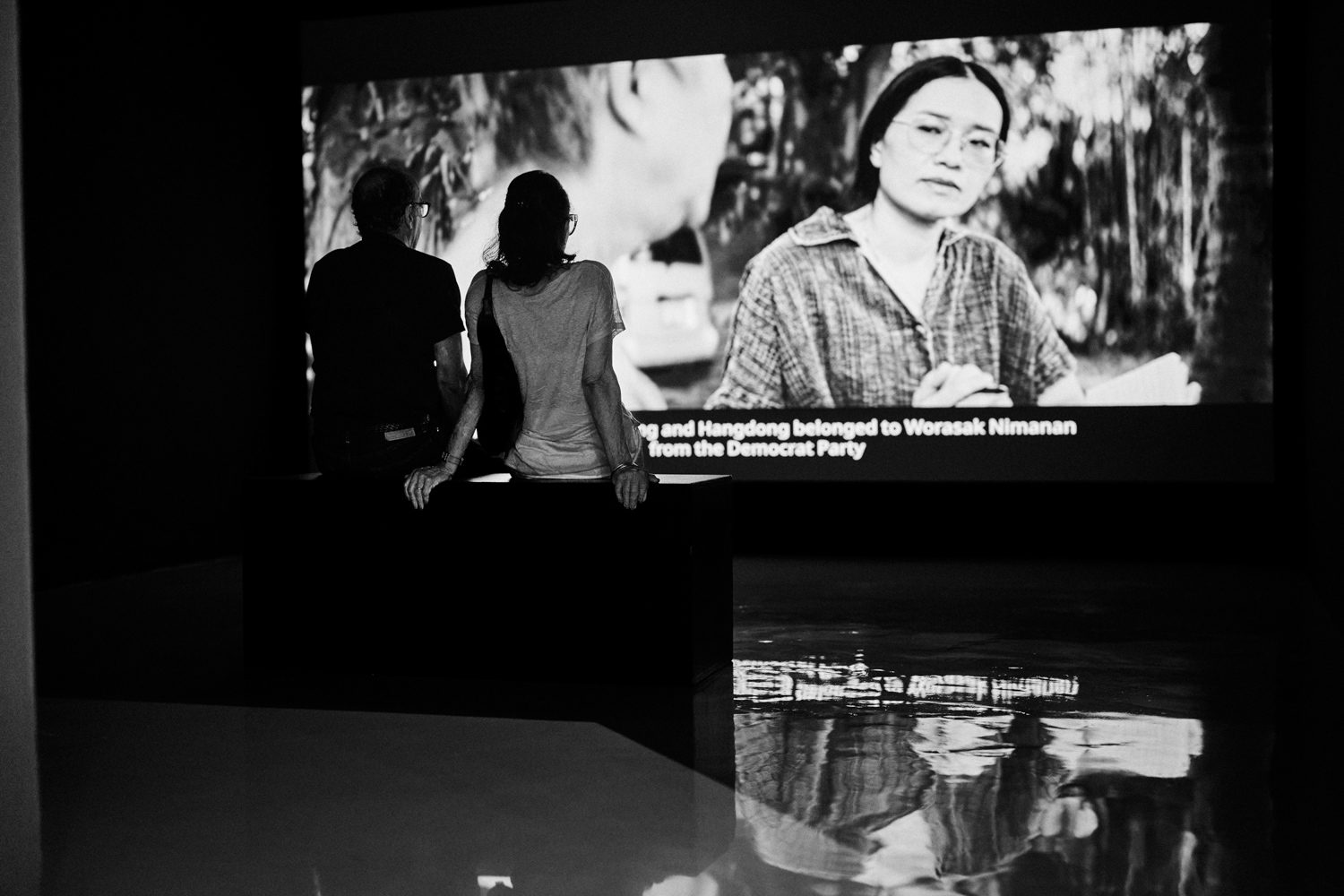

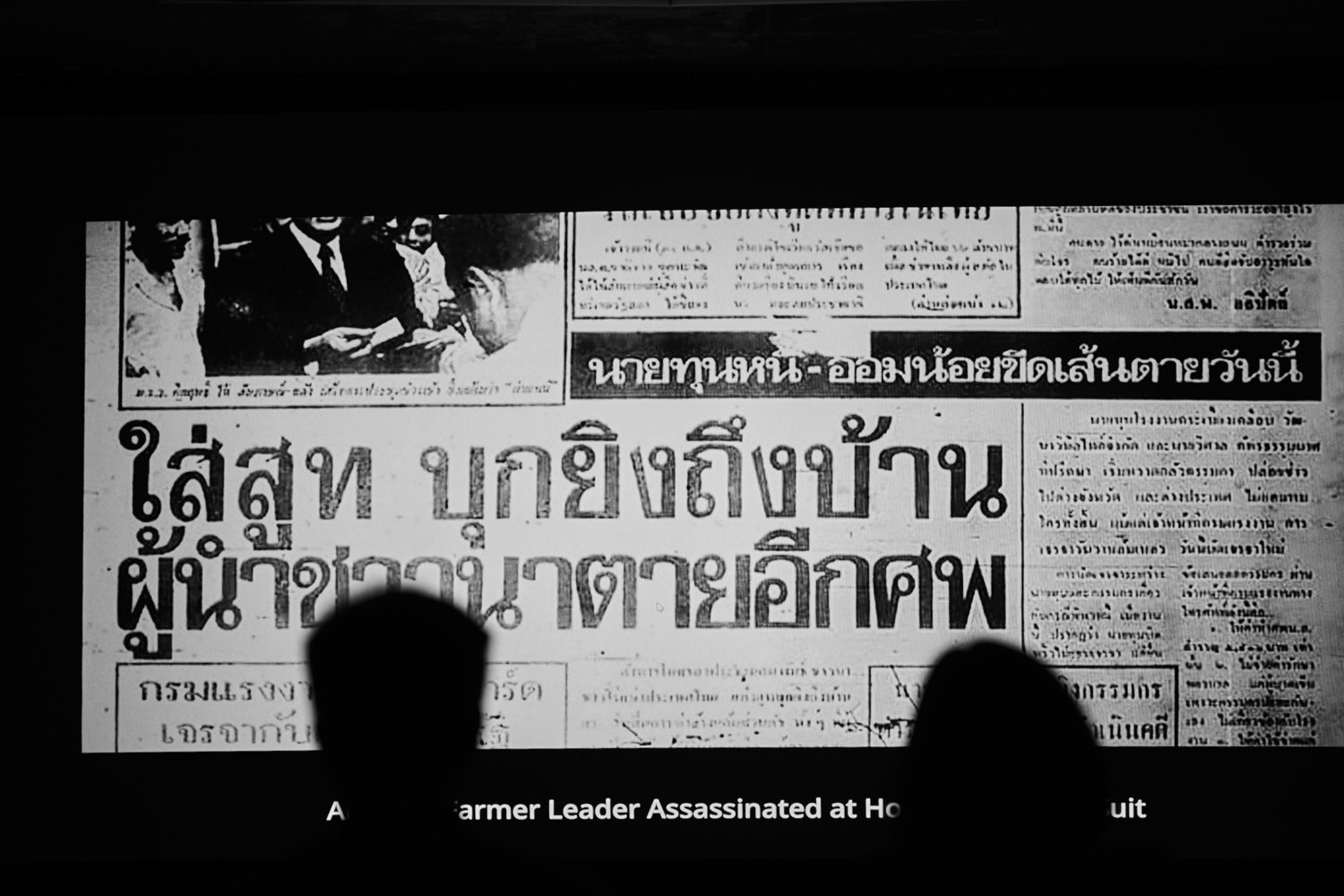

Among the works featured in Toxic Remains is the screening of the documentary ’TURNING THE BHUMI: The Uprising of Peasants in Northern Thailand, 1974-1976’, directed by Sorayut Aiemueayut. The film chronicles the historic movement of farmers in Northern Thailand who, between 1974 and 1976, rose to reclaim their right to farmland amid the country’s political transition from dictatorship to democracy. In Chiang Mai and Lamphun, farming communities united to resist both the entrenched landlord system and the weight of traditional hierarchies that continued to press down on their lives.

This struggle was never solely about livelihoods. It also exposed the ongoing contest for moral authority embedded within the maxim that ‘everyone has their reasons for proving themselves right.’ When one side invokes reason, virtue, or tradition to legitimize the oppression of others, refusing even to acknowledge the humanity of those who, like themselves, have lives, thoughts, dreams, and families, the farmers’ fight in the documentary ceases to be only about rights. It becomes an unmasking of the mechanisms by which Thai society manufactures ‘rightness’ out of the enforced silence of those rendered invisible. The inclusion of this documentary in ‘Toxic Remains’ is therefore not simply an act of revisiting the past and remembering. It is a stark reminder that the ‘toxic remains’ of ideology and power are still embedded in the scaffolding of Thai society, whether in the form of class hierarchies, titles of nobility, systemic inequality, or the discourse of virtue wielded as a weapon to destroy one’s opponents.

Breaking Boundaries: Art and the Act of World-Building in Minecraft

During his time at home with his son, Thasnai noticed the boy’s deep absorption in the game Minecraft, a virtual space where players can construct entire worlds of their own design, unbound by fixed rules or predetermined limits. Curious, he began asking about the game’s origins and discovered that Minecraft is far more than a children’s pastime. It has become a global phenomenon, embraced by young people across cultures, its very simplicity opening an expansive arena for the imagination to roam freely.

His interest deepened when he realized that Minecraft, launched in 2011, emerged in parallel with waves of popular uprisings across the world: the Arab Spring, which began in Tunisia and swept across the Middle East, and Occupy Wall Street in the West. In their own ways, these two realms, one virtual, the other rooted in the streets, embodied attempts to ‘reclaim space’ from long-established powers, challenging the structures that confine the dreams and possibilities of a new generation.

While the Arab Spring claimed public squares such as Cairo’s Tahrir Square to push for political transformation, Minecraft offered a virtual expanse where players could build new worlds from scratch, governed only by the rules they chose to set. Thasnai recognized a thought-provoking parallel between these two acts of reclamation and invited his son to create a Dreaming World, an ideal world unbound by inherited structures, within the game. He then incorporated images of this imagined city as one of the layers in his artwork, using it as a test ground for a question at the heart of his practice: how might a ‘dream’ grow when freed from the old architectures of power and control? From his son’s perspective, the world is a playground for creation, and Minecraft becomes a potent symbol of freedom that adults too easily forget. In his hands, the game’s virtual space becomes a field of imagination; childlike in its innocence yet resonant with the depth of social possibility. It is both a dismantling of the old world and an opening toward a new one, sustained by hope and unshaped by the constraints of the past.

Epilogue: Art as a Voice of Hope for the Next Generation

Ultimately, ‘Toxic Remains: Parasites of a Betrayed Dream’ does more than invite us to look back at the past. It reveals how the past has never truly faded. It is subtly reproduced, subtly and systematically through the discourse of virtue, the drawing of lines to determine who is ‘right,’ and through the power structures that erase certain voices from history. ‘Toxic Remains’ traces the residues still embedded within the social fabric and collective consciousness, suggesting that art remains one of the few spaces capable of making such toxins visible, and of opening a path toward a shared humanity built on mutual recognition and equality.

‘Human civilization has developed over thousands of years; otherwise, we would still be living in caves.’

To move forward, then, is to strip away old constraints, to question the status quo, and to refuse to allow any one person or group to monopolize the truth.

Thasnai Sethaseree wields art as the most powerful tool at his disposal; to guide society and reclaim moral authority as a shared social asset, rather than the possession of a select few. His work stands as a reminder that while the toxic remains of history persist, the value of the dreams and hopes of future generations is not only worth collectively protecting, it is essential to our survival.

‘Toxic Remains: Parasites of a Betrayed Dream’ is on view at Gallery VER from 19 July to 20 September 2025.