THE EXHIBITION BY PRATCHAYA PHINTHONG HAD DISMANTLED BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY’S ‘WHITE CUBE’ LOOK. THE BUILDING IS STILL A GALLERY, BUT ITS VERY CLAIM TO BE AN ART SPACE WAS STRIPPED

TEXT: TUNYAPORN HONGTONG

PHOTO: KETSIREE WONGWAN

(For Thai, press here)

Before stepping into A Solo Project, Pratchaya Phinthong’s latest exhibition at BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY, curiosity loomed: just how complicated, or costly, could this endeavor possibly be? The question had emerged earlier by an interview with the gallery’s co-founders, Supamas Phahulo and Akapol Sudasna, which I stumbled upon in EQ. They recalled that after inviting Pratchaya to put together a show in celebration of the gallery’s tenth anniversary, the artist disappeared for a couple of months, only to return with an idea. Before revealing what it was, he preemptively disarmed them with a warning: “You don’t have to do this if you don’t want to.”

The reason for his hesitation became clear the moment one set foot inside. What Pratchaya had done was nothing less than dismantle the gallery itself: removing every door and pane of glass until both the main exhibition hall and the BOOKSHOP LIBRARY looked somewhat like a gutted shell, caught mid-demolition. Every object had been carted away. With the windows gone, branches from the trees outside reached into the emptied space, rain spattered the exposed floor, and snails wandered in at leisure, sometimes joined by other creatures. From the street, the transformation was jarring. The white-box gallery on Sathorn Soi 1, usually so pristine and aquarium-like, now looked abandoned. Passersby speculated: had it closed for good? What a pity. Why was it shut down? Some even ventured inside to ask whether the place was up for lease, imagining it being repurposed as a matcha café…

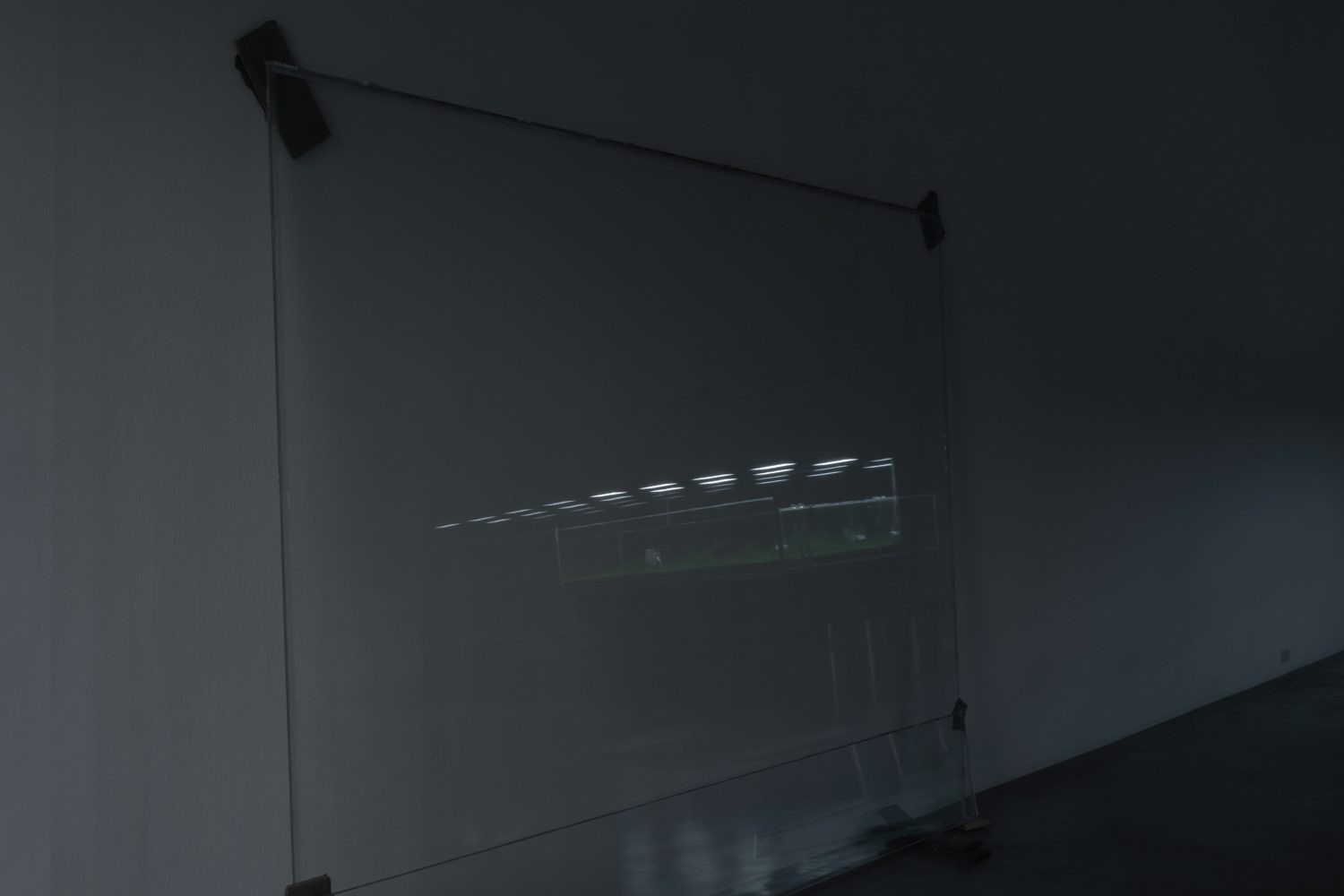

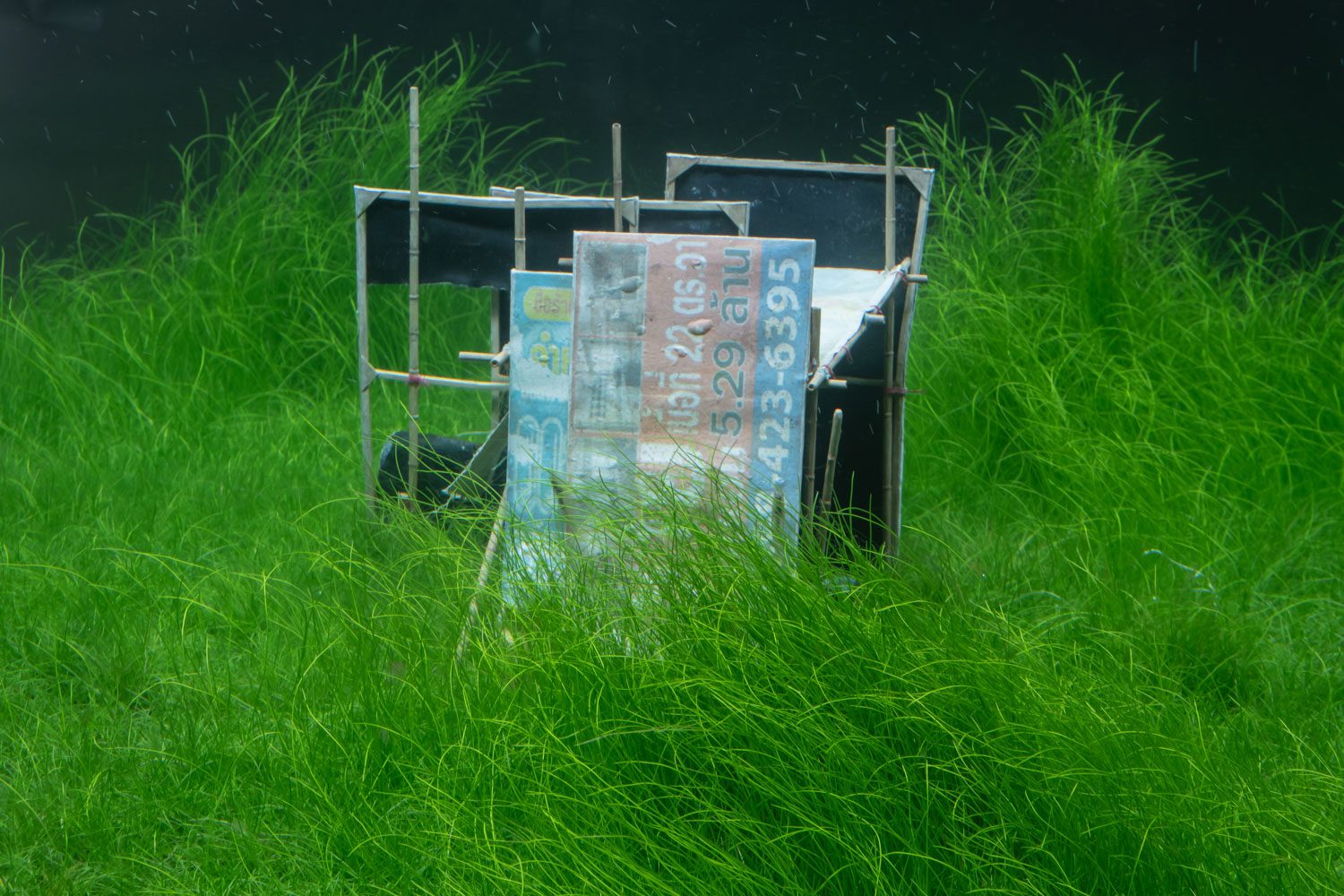

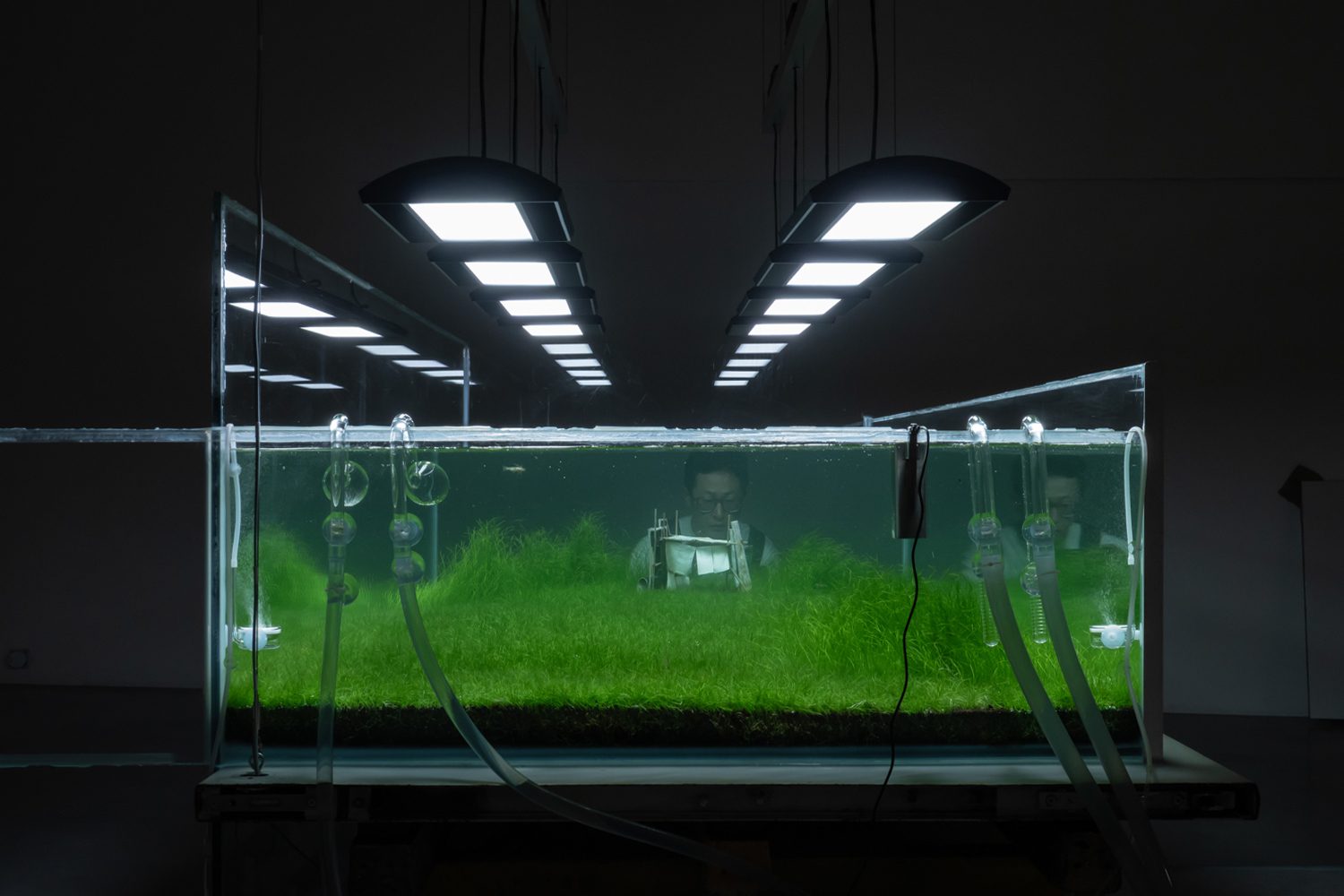

Some of the dismantled doors and panes of glass were propped casually against the gallery walls, scattered into corners. The rest had been reassembled into a massive glass tank. It resembled an aquarium, albeit one without fish, installed at the center of the room. In truth, the structure functioned less as an aquarium than as a terrarium. Inside, aquatic grass had been planted; tiny freshwater shrimp darted about; an oxygen pump and fluorescent lighting sustained the miniature environment, ensuring that photosynthesis could take place. Over time, the grass flourished. From the barren appearance on opening day, the tank had transformed by the time of my visit, its greenery spreading into a lush carpet that provided food and refuge for the shrimp. The effect was that of a self-contained micro-ecosystem. At its base, the tank housed a model of a makeshift shelter reminiscent of those built by the urban poor, often cobbled together from discarded advertising billboards. One of the salvaged panels still bore the words ‘For Sale.’ Glass and water combined to multiply these fragments into a hall of reflections, producing illusions and visual misdirections at every glance.

Assembling an aquarium from panes of glass and doors never designed for such a function came with inevitable complications. In the early stages, the team struggled with leaks; grooves had to be cut into the gallery floor so the massive sheets could be slotted securely in place. During this process of dismantling and reconfiguration, the gallery called back the very same glazier who had first installed the windows ten years earlier, asking him to evaluate the feasibility of the undertaking. And as the project unfolded, the questions multiplied. Why a terrarium? Why dismantle the gallery’s own doors and windows only to reassemble them into a tank? Why place a plastic bag filled with soap, molded into the form of a fish, atop the edge of a doorframe? Why insist that the exhibition remain open twenty-four hours a day? Should the security guard stationed on site now be considered part of the work? And where, in the meantime, were the gallery staff expected to work? The glazier, seemingly peripheral to the world of contemporary art yet present at both the gallery’s original construction and this strange reincarnation, posed perhaps the sharpest question of all: “Why are we doing this?”

Pratchaya’s art has long tended to provoke questions rather than deliver answers, and many of those questions concern the very space of art itself. In Who will guard the guards themselves (2015), staged roughly a year after the 2014 military coup, he constructed a structure on the plaza outside the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC), a site that had seen numerous political gatherings over the years. Inside this structure was a white cube resembling a gallery, hung with photographs of 7-Eleven convenience stores taken on the first night martial law was declared. Yet the artist locked off all four walls, preventing anyone from entering. Viewers were forced instead to stoop down and peer through a transparent strip of glass at the base of one wall.The questions raised were layered and unsettling: questions about the rights and freedoms of audiences and artists within cultural institutions, and by extension, the rights and freedoms of citizens in public space, or perhaps within their own country altogether. In that work, Pratchaya also placed a camera inside the simulated gallery and broadcast the feed live to another exhibition of his taking place simultaneously in Paris.

This act of linking two art spaces across distant geographies resurfaced in This page is intentionally left blank (2018), his first exhibition with BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY. For that project, Pratchaya borrowed the daily logbook from the National Gallery (Chao Fa Gallery) and placed it on display, while also painting the gallery walls with A1000 white, the very shade recently used to refurbish the Chao Fa Gallery’s own walls, before overlaying them with the pristine white of the white cube at BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY. The effect was a mise en abyme of whiteness, a blankness that was anything but empty. Within this context, even the most ordinary object, such as a cast concrete parking barrier that he had removed from the gallery’s own rear lot, was reconstituted as art.

This page is intentionally left blank marked the first time Pratchaya set about ‘dismantling’ something tied to BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY. Back then, it was by removing a cast concrete parking barrier. In A Solo Project, the scale is more monumental, as he takes apart the very doors and windows of the gallery itself.

Yet the two acts of dismantling carry very different meanings. In the first, the artist relocated a banal object into the sanctified space of the gallery. The authority of the white cube, its walls freshly painted in A1000 white, which was the same shade used at the National Gallery, conferred upon that object the status of art. By contrast, in this new work, Pratchaya’s dismantling seems to strip the gallery of its very claim to be an art space. From a closed, pristine, and hermetically sealed white cube, it has been converted into an open passageway where the outside world spills in: the weather, the branches, even the sound of traffic. Anyone may walk in at any hour of the day or night. With the aura of the white cube fading, the parking barrier from This page is intentionally left blank, once canonized as art and now used as the base of the aquarium, begins to revert to an ordinary object.

This was what we encountered on the day we visited the exhibition. Yet three or four days later, while drafting this article and still caught up in the pleasure of interpreting his work, another perspective began to take shape. Perhaps Pratchaya had not, in fact, dismantled or diminished the gallery’s status as an art space entirely. The gallery still remained, only compressed, as if the artist had condensed the white-cube building into a terrarium… A terrarium pieced together from the very doors and windows that once enforced the gallery’s authority as a sealed, exclusive space.

The more pressing question, then, may not be whether this aquarium still carries that same spatial authority. Rather, what if we read it as a model of the gallery itself? Would it suggest that the art world, too, sustains its own micro-ecosystem, one maintained by oxygen tubes and synthetic light much like a terrarium, and marked by its stark separation from the outside world? And if so, what other implications follow? What further questions should we be asking?

On the occasion of BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY’s tenth anniversary, this may be one of the most compelling questions the work leaves behind. But before turning to larger interpretations, the gallery team faces a more immediate puzzle: once A Solo Project closes on September 13, what will become of the doors and windows that have been dismantled and reassembled into an aquarium? Should they be restored to their original place, or will the space be reconfigured altogether? And after serving for weeks as the glass and frame of an improvised tank, submerged in water and repurposed into another ecosystem, can these elements ever truly return to being the structural fabric of an art space?

‘A Solo Project’ by Pratchaya Phinthong runs from July 18 to September 13 at BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY (open 24 hours).