art4d SPEAKS TO SIRASAR BOONMA, ONE THE FOUNDER OF HEAR & FOUND, A CREATIVE AGENCY WHOSE MISSION IS TO HELP THE GENERAL PUBLIC BECOME MORE AWARE OF FRAIL MARGINALIZED PEOPLE WITH SMALL VOICES THROUGH MUSIC

TEXT: PRATCHAYAPOL LERTWICHA

PHOTO COURTESY OF HEAR & FOUND

(For Thai, press here)

As much as one would like to believe that the world has evolved well enough for people to freely express themselves, the reality is that some voices are louder than others. It is always difficult for certain groups of people’s voices to simply be heard, no matter how elaborate or loud the words are uttered. The voices of people from indigenous tribes and ethnic groups are among those that are frequently lost along the way. They have been calling, asking for people to try to understand who they are after being stereotyped and stigmatized by society as people who burn down forests or are even called drug dealers, despite the fact that the truth isn’t always what it appears to be.

Sirasar Boonma (Mae) and Pansita Sasirawith (Rux) are the two founders of Hear & Found, a creative agency whose mission is to help the general public know and understand more about marginalized people with small voices through music, somethingit is an area in which they both have expertise and experience. They have put together projects that expose people to voices they may have never heard or been exposed to, through events such as the World Music Series concert, a live music performance that tells stories of ethnic groups through music, or the Sound of the Soul exhibition at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center, which was held last year and introduced the audience to the marginalized voices of ethnic people in Thailand.

What motivates them to become the voice of the marginalized? Is what they’re doing actually making a difference in society? Open your ears and your mind, and let’s get to know Hear & Found in this conversation between art4d and one of the founders, Sarisa Boonma.

Mae Sirasar Boonma (Left) and Rux Pansita Sasirawith (Right)

art4d: Would you mind giving us a brief overview of who Hear & Found is and what your agency does?

Sarisa Boonma: We define ourselves as a creative cultural agency. We create projects that benefit our collaborators, who are primarily people from various ethnic groups and communities, using our expertise and experiences in music and event organization. We provide channels and platforms for them to talk about their problems, stories, and cultures while also introducing them to outsiders and the general public. Our previous projects included the World Music Series Concert, in which we invited individuals from different ethnic groups in Thailand to play music and showcase their ways of life so that more people could learn about who they truly are rather than through stereotyped narratives created by the media. When members of the Talat Noi Market community were struggling with their income due to COVID-19, during Bangkok Design Week 2022, we collected ASMR sounds from various shops and composed a song to help promote the local vendors.

World Music Series by Hear & Found

art4d: What inspired the creation of Hear & Found?

SB: It all started with Pansita Sasirawuth (Rux) and myself. We met at a company that specialized in community tourism, which is a branch of tourism that advocates for community development to assist local communities in receiving equitable benefits from the tourism industry and to become self-sufficient.

We visited a village while working together. The village was well known for its traditional textile weaving and dyeing products. When we asked the locals if the younger generation was still interested in creating these crafts, they said there were only two young people interested, compared to the parents’ generation, which had about 20 people who knew how to master these crafts. Members of the younger generation either open motorcycle shops or work in other fields. It made us realize that there is a strong possibility that these invaluable crafts will vanish one day, and it led us to ask many more questions about the possible disappearance of other local crafts and wisdom in Thailand.

We were considering any opportunity or approach that could help preserve these local cultures and wisdom for future generations, as well as whether we could make a living working in this specific field. From there, we attempted to join the School of Changemaker, which organizes these types of business for society projects, and they encouraged us to think about how the loss of local cultures can be problematic for society.

The exhibition in World Music Series by Hear & Found

Then Rux was trying to figure out what causes the loss of cultures and which groups of people would be most affected by it. After doing some research, we discovered one of the issues that people from ethnic groups and indigenous tribes in Thailand face. We found that this particular group of people had been misidentified for a number of reasons. For example, some media outlets have falsely blamed the Pga K’nyau people for deforestation caused by swidden agriculture, and people who have consumed this information have this bias or generalized idea about the Pga K’nyau people. People from this culture have been subjected to a range of different difficulties as a result of this misperception. Some Pga K’nyau children are bullied simply for wearing their own tribal clothing, others are mocked for their accent, and all of this has led to many of the younger generation feeling ashamed of their own culture. It is one of the possible causes of a culture’s extinction, and it is one of many forms of cultural loss that our country is experiencing. Apart from the misunderstanding, this group of people are also dealing with a slew of other social issues as a result of not being given a proper nationality and access to the basic rights of Thai citizens, such as healthcare, education, and land ownership.

However, through our work with local and ethnic communities across the country, we learned so much about these people in ways we hadn’t known before, such as their ways of life and how they live and coexist with nature, their culture of making clothes and textiles using natural dyes, and even their music. We had the idea that we could use our abilities, skills, and expertise to create this platform for outsiders and the general public to see and experience these things from a different perspective.

Rux and I were trying to figure out what we could do, and look into what we were good at. At the time, we discussed the possibility of using music as a medium. I studied music and previously worked in event planning. Rux has worked in public relations. With that as a starting point, the School of Changemaker provided us with funding to undertake a pilot project. So we organized a musical event. Dipunu, a Pga K’nyau man and musician, was invited to perform and share his stories. Leletenaku is the name of a song. So, “lele” is similar to singing “lala” to the beat of a song, whereas “tenaku” is the name of a Pga K’nyau musical instrument. The lyrics to the song are very interesting. It talks about the concept of environmental conservation, with parts of the lyrics that say, “We coexist with the forest, we cherish the forest.” We drink the water, therefore we treasure it. We eat the frogs and look after the mountains. “We have the fish, so we protect our creeks.” The lyrics are in both Thai and Pga K’nyau. That event provided an opportunity for the owners of these cultures to be the storytellers of their own stories, and it sparked new exchanges in a new realm and territory through the use of music.

Dipunu, the Pga K’nyau musician

art4d: How was the response to your first event?

SB: The tickets were all sold out. We asked each of the over 30 people who attended the concerts if they got the messages and if their feelings had changed before and after the show. Nearly 80% of the audience understood and recognized the underlying issues. It proves how music can help people better understand the Pga K’nyau people and their way of life.

We invited this group of Pga K’nyau musicians to participate in other activities after the debut project. The United Nations Development Program then contacted us to speak at one of their events, and these Pga K’nyau musicians were invited to perform. The UNDP team was then introduced to the village from which the Pga K’nyau originally came, and they visited their village together. It provided them with an opportunity to discuss their culture and wisdom, as well as find solutions to their problems. That gave us hope that what we were doing could actually make people’s voices heard.

Dipunu, the Pga K’nyau musician

art4d: What is the first thing you do when you start a new project?

SB: Typically, we would begin with an issue or aspect that interests us or a local culture that we want to learn more about. From there, we would travel to their home. We would ask for permission to live in their households, learn about their way of life, and attempt to comprehend the nature of the community. We asked the Pga K’nyau people if we could live in their village so that we could learn about their culture and lifestyle, including swidden agriculture as the initial part of the first project we did. We got to see the real swidden fields while we were there. We presumed it would be like the large-scale farming that destroyed vast forests, but we later discovered that it was only small plots of land for each household. After the harvest, the lands will be left to grow trees and eventually become part of the woodlands again. It usually takes 5-7 years for the ecosystem to regenerate naturally. When we saw it with our own eyes, it became clear that there had been a misunderstanding.

Then we considered how we could convey these messages to the general public. We want to accomplish three things in particular. The first is what the community will get in return and whether what we’re doing goes along with their objectives. The second question is whether what we’re about to do is relevant to the problem we hope to solve. The third is the people who participate in our project, such as the viewers, and the ideas they will bring back with them even after the project is completed. Most of the projects we’ve worked on aren’t just about music, but about people or communities. The World Music Series concert we organized included a photography exhibition so that attendees could see what real swidden farming looks like.

World Music Series by Hear & Found

art4d: How did you guys adapt during the pandemic, when offline events were impossible?

SB: During COVID, we did think about how we could continue to communicate these stories about people from ethnic groups in a way that everyone could also sustain themselves financially. We then tried to sell our music and sound licenses, which are basically licenses to use the sounds and music created by these tribal people. It is also a means of promoting indigenous music and generating income for the artists. We created the Stock Music and Sound Platform after a period of experimentation. We chose this route because I previously worked for a post-production company that specialized in sounds. And because the use of sounds in various media platforms typically involves the purchase of sounds and music from musical libraries, this project has become both a channel for communicating these people’s stories and a source of income for the artists and ethnic communities.

Hear & Found’s website – www.hearandfound.com

art4d: Could you tell us a little bit about the Sound of the Soul exhibition that you did with BACC?

SB: This was our first project with BACC and other senior artists such as the Duckunit team, who designed the space, and the photographer Supachai Ketkaroonkul. BACC asked us to help with the creation of a space that would help introduce Thailand’s diverse art and cultures, and the event encouraged viewers to consider the values and beauty of how diverse humans are.

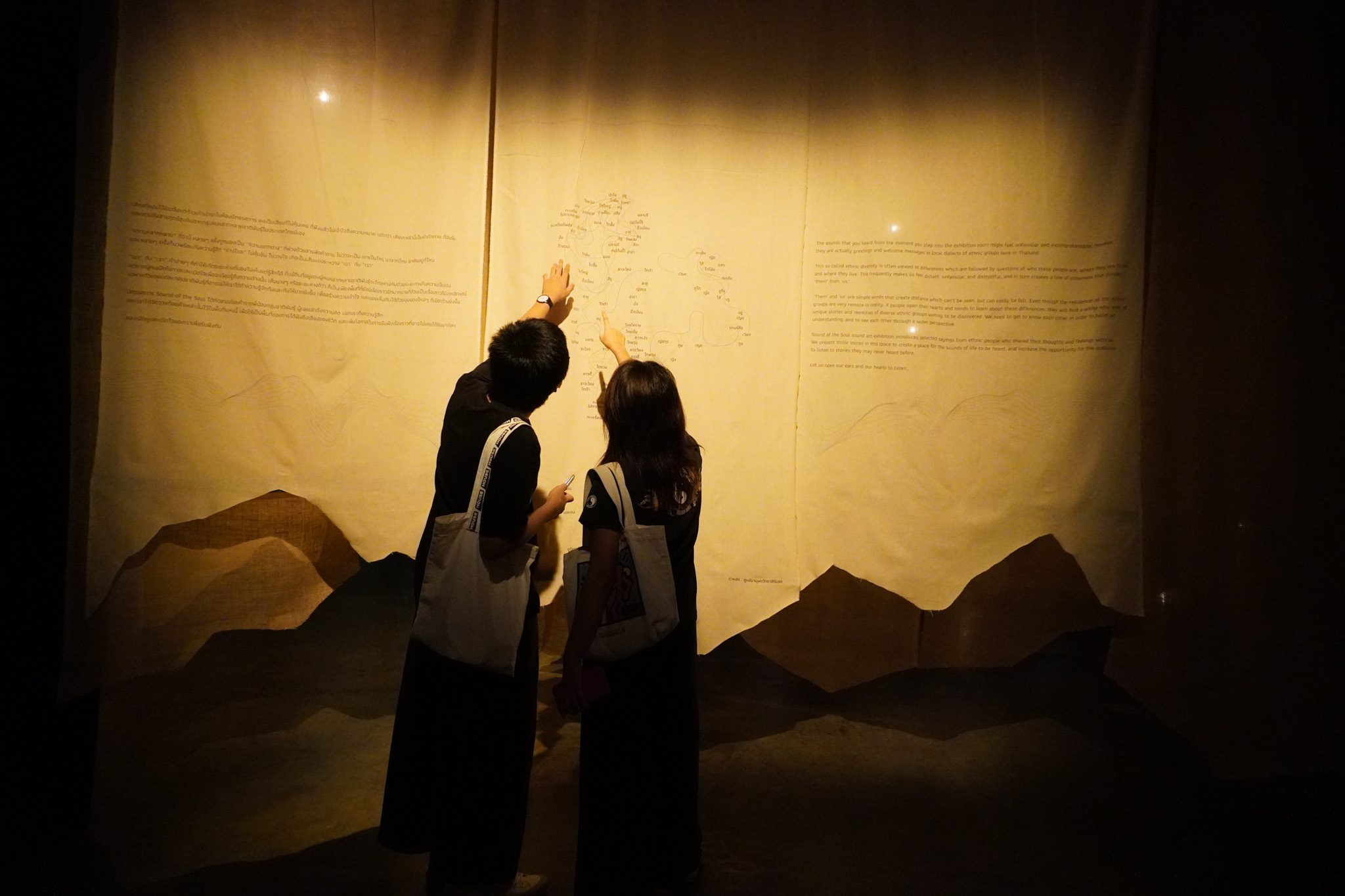

Sound of the Soul exhibition at BACC

From our perspective, the key message of the exhibition was for people to gradually discover and listen to all of these voices, as well as learn about various ethnic groups in Thailand. The exhibition was divided into three parts. The first zone was dubbed “peeling the skin,” and it demonstrated how Thailand is home to a variety of ethnic groups. The following zone depicts these people’s various lifestyles. The ending was our attempt to convey the message that, in the end, the wall that divides mankind does not exist in the first place. Perhaps this wall has been built solely out of people’s imaginations, and once it is removed, we will be able to understand each other more. The exhibition’s ending is actually its beginning. It’s a complete loop.

Sound of the Soul exhibition at BACC

We installed speakers in numerous places, and the sounds were recorded from the actual locations where they originated, such as the sound of insects flying, pigs making oink noises, or people speaking, which were taken from our interviews with individuals from different ethnic groups. It was the space that prompted viewers to pay close attention and get to know all of these diverse groups of people. The exhibition space invited visitors to go on a journey to discover all of these sounds. We believe that the opportunity to collaborate on this exhibition with a government agency like BACC is a fantastic way to communicate with the public because it allows us to create a platform for people whose voices have never been heard before to tell their stories.

Sound of the Soul exhibition at BACC

art4d: When people work with people from ethnic or marginalized groups, there’s usually a question regarding their intentions and if they are exploiting and profiting from this vulnerable group of people. How does Hear & Found operate to make what you guys are doing something that isn’t benefiting these people?

SB: We make sure to position our approach and how we work with the ethnic people as a collaboration. We don’t see ourselves as their saviors or superiors. We consider our collaboration to be an effort to solve problems. Each party has their own unique expertise and skills, and everyone works together to make things better. We usually go in with the intention of trying to understand the problems and asking these people what they wanted to communicate or what problems they wanted to solve, as I mentioned earlier. We would walk away if we told them about our expertise and they said they were not interested. We will not force or manipulate them into doing something they do not want to do, nor will we give them false hope that their problems can be solved because, at the end of the day, they are the people who are at the center of the problems. They are the ones who must deal with these issues. So it’s really up to them when it comes to what they want or how they want things done in order to reconcile these issues.

art4d: What do you think the appeal of indigenous music is?

SB: I believe these people’s music are similar to teachings. It’s a collection of folk tales with rhymes and rhythms. It is derived from how these people lived and passed down their way of life. Their musical instruments are one-of-a-kind. They’re shaped like guitars or drums, but some are made of bamboo and produce truly unique sounds.

art4d: We share your concern for the disappearance of culture and ethnic groups; is indegenious music also going to disappear?

SB: The term “culture” encompasses so much more than just music, and everything is subject to extinction with each passing day. We are aware that the demise of this style of music is always a possibility. The impact of this loss is that Thai people will never have the opportunity to learn about the incredible diversity of such styles of music, their distinctive sounds, and the lives and places of the people who created them, along with the musicians, makers of musical instruments, and those who use and preserve these pieces of culture. If these things disappear, so will parts of our culture. But if we can create access to these cultural assets or vernacular sounds and music, the likelihood of music or cultural stories being discussed, heard, or evolving and reviving will be even greater. The impact will be felt by the people who own the cultures, including those in this profession, who will have more opportunities to communicate or more platforms on which to create and showcase their works.

However, in countries with rigorous cultural support, such as Canada, there are policies in place to promote economic opportunity for indigenous musicians. It spawned the indigenous music industry and exported music festivals that are so successful that they contribute significantly to the nation’s gross domestic product. Every year, Malaysia hosts the Rainforest World Music Festival, which is attended by 20,000–30,000 people and generates an eight-figure revenue each year. But Thailand has such a limited room for this industry, and it’s not because we don’t have indigenous musicians because there are so many young generation Pga K’nyau musicians. But there are still many gaps, such as these gaps in opportunities that can increase public access to this type of music or these pieces of culture, or allow for the emergence of new talents and creations, particularly among artists who are not part of the mainstream music industry. There is a need for more investments and support in the development of people’s talents and abilities, production, marketing, and communication strategies in ways that truly understand and value indigenous cultures.

art4d: How do you envision the future of Hear & Found?

SB: I want us to be one of the organizations that comes to mind whenever cultural diversity is discussed, particularly when it comes to the support of ethnic groups and indigenous people. We’re not limited to music alone; it could branch out into things in the future, but we want more people to join us so that we can all move forward together and so that these diverse cultures in our country are better recognized and based on a genuine acceptance of diversity.

art4d: How does Hear & Found envision the future of our society?

SB: Rux and I share the same vision of a society that accepts diversity in its entirety. There are a variety of stereotypes and generalizations about race, skin color, body proportions, and even genders, and we often hear insults and jokes that can be very hurtful to some individuals. The question is why we don’t try to listen to what they have to say and find out whether things are truly as they appear, or whether we should respect people for who they are rather than judging them based on their appearances. We envision a society where people can sit down and talk and accept that we’re all different, but that’s okay, and I want to hear your stories, and where everyone can be proud to be who they are.