BREAKING CHAINS, CLAIMING FREEDOM: AS THE STATE TURNS WORDS INTO SILENCE, HTEIN LIN’S EK KHA YA SPELLS THEM ANEW

TEXT: KANDECH DEELEE

PHOTO COURTESY OF WEST EDEN EXCEPT AS NOTED

(For Thai, press here)

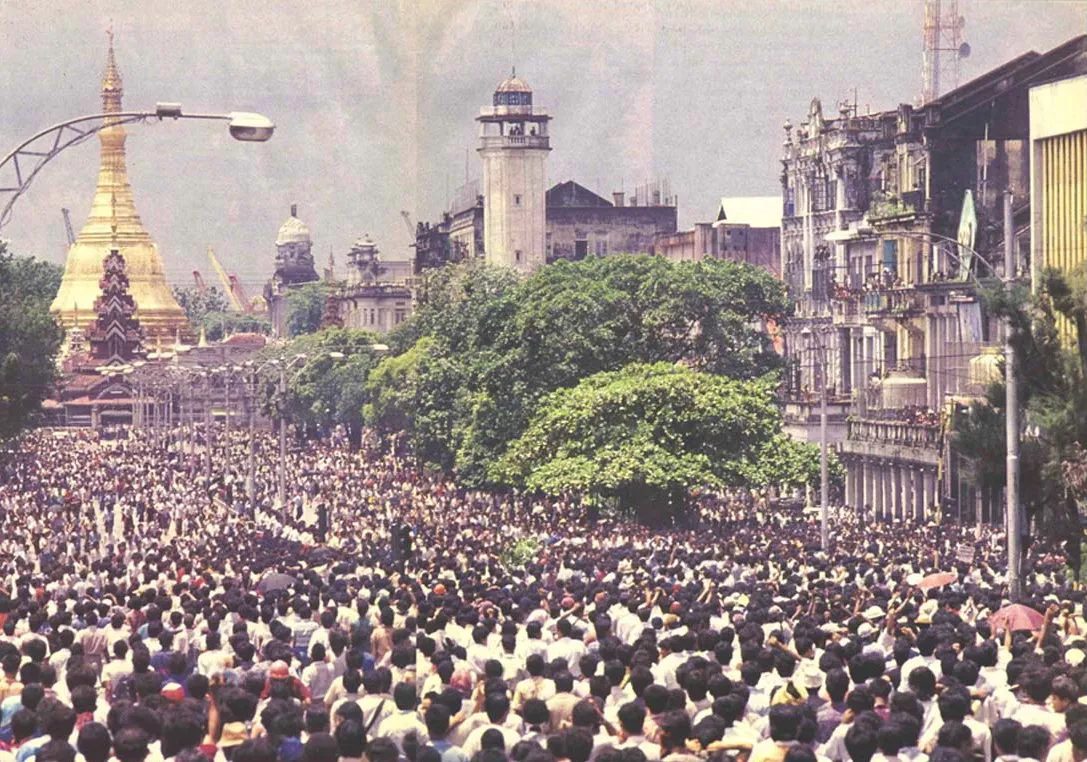

Since gaining independence from Britain in 1948, Myanmar has spent nearly eight decades in a state of recurring unrest.1 The country’s history has been marked by protracted clashes between successive governments and ethnic armed groups, compounded by the monopolization of executive power that has undermined the economy and, time and again, intensified tensions between the state and its citizens. Among the most consequential of these crises was the ‘8888 Uprising’ of August 8, 1988, when hundreds of thousands of people poured into the streets to protest against the military regime that had held power since 1962. Although the demonstrations culminated in the resignation of General Ne Win as party leader,2 the shift came at a devastating cost: widespread civilian casualties, the deployment of heavy weaponry against protesters, and mass arrests carried out by the state.

8888 Uprising | Source: https://burmese.voanews.com/a/call-in-88ers-meet-their-expectations/3977245.html

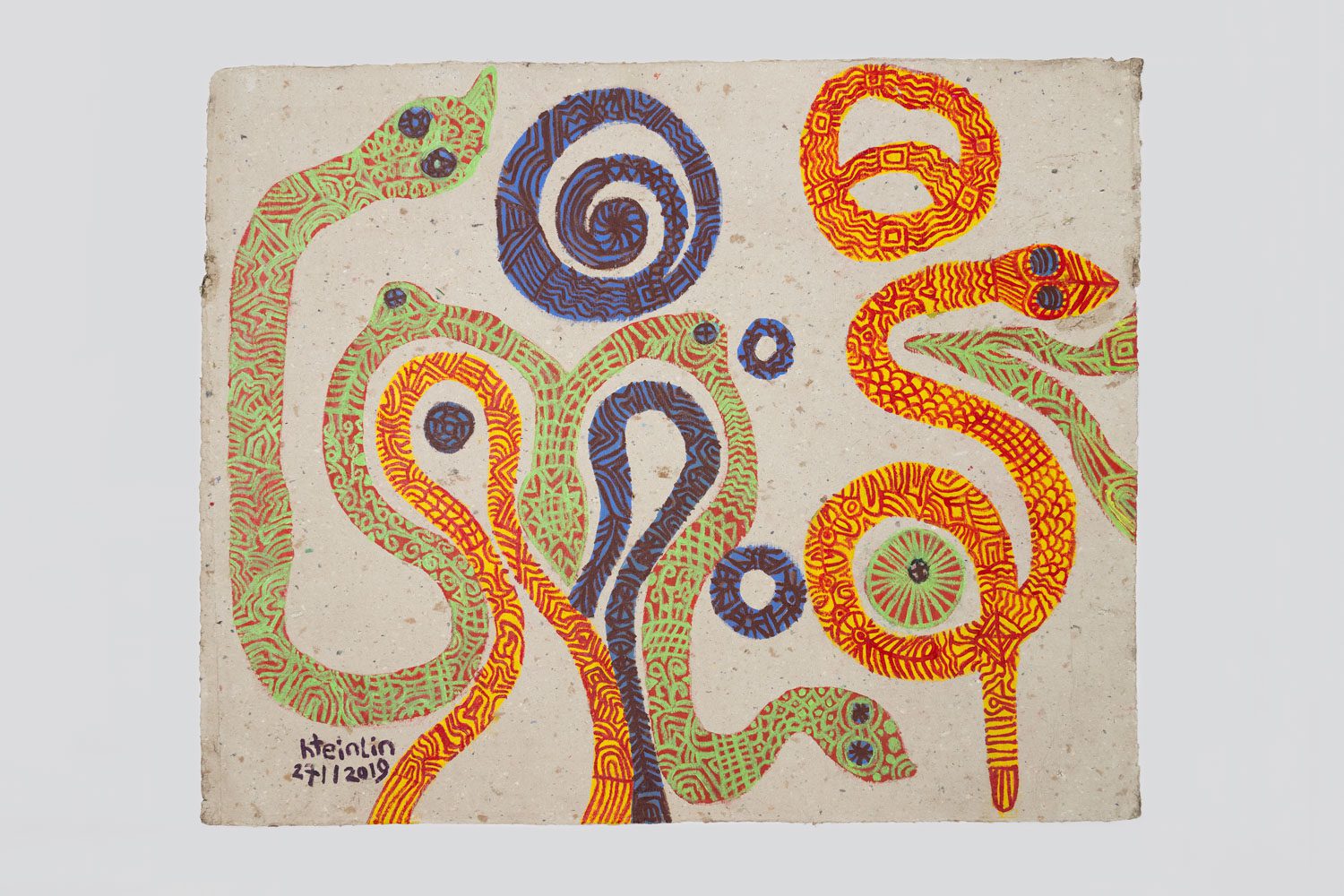

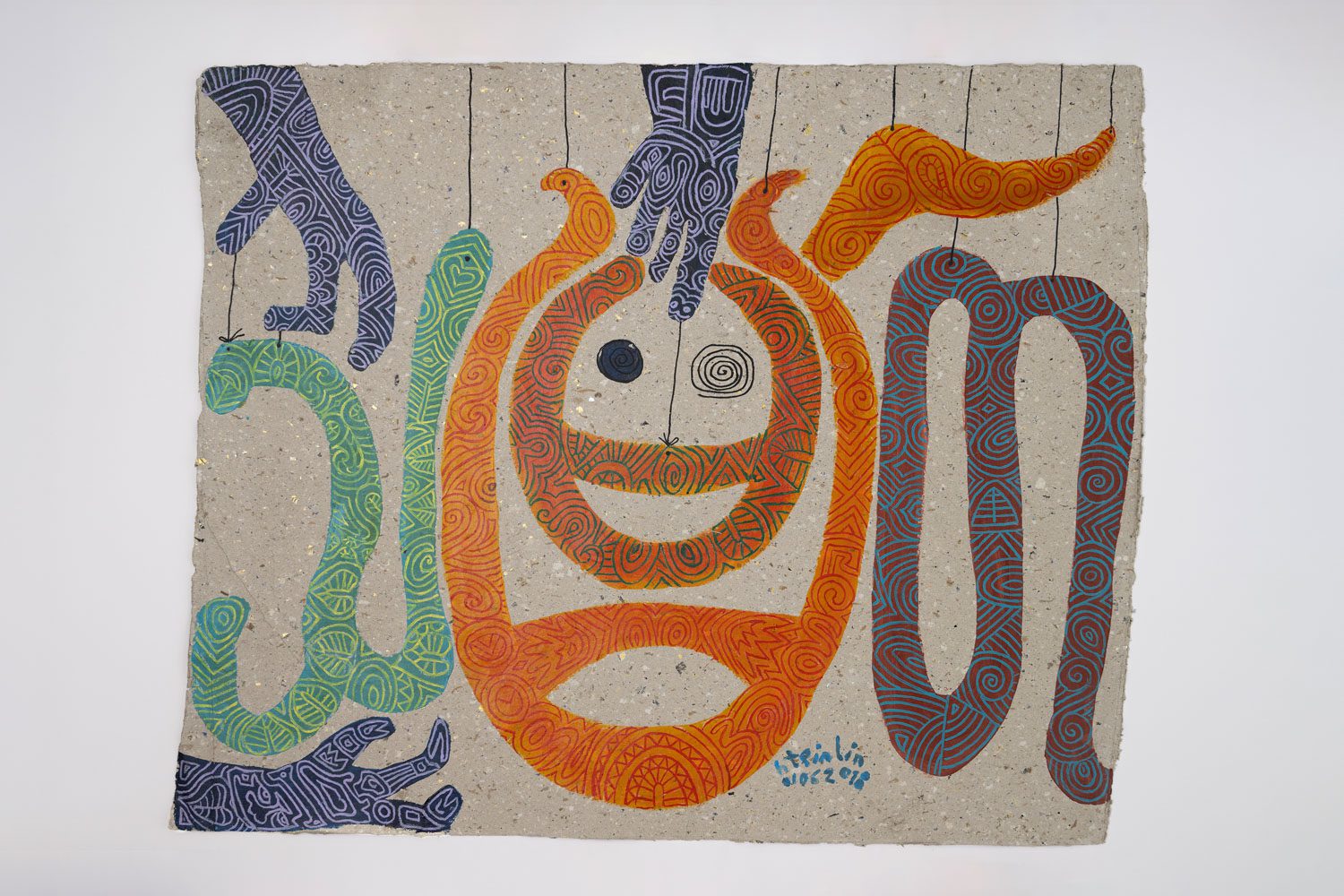

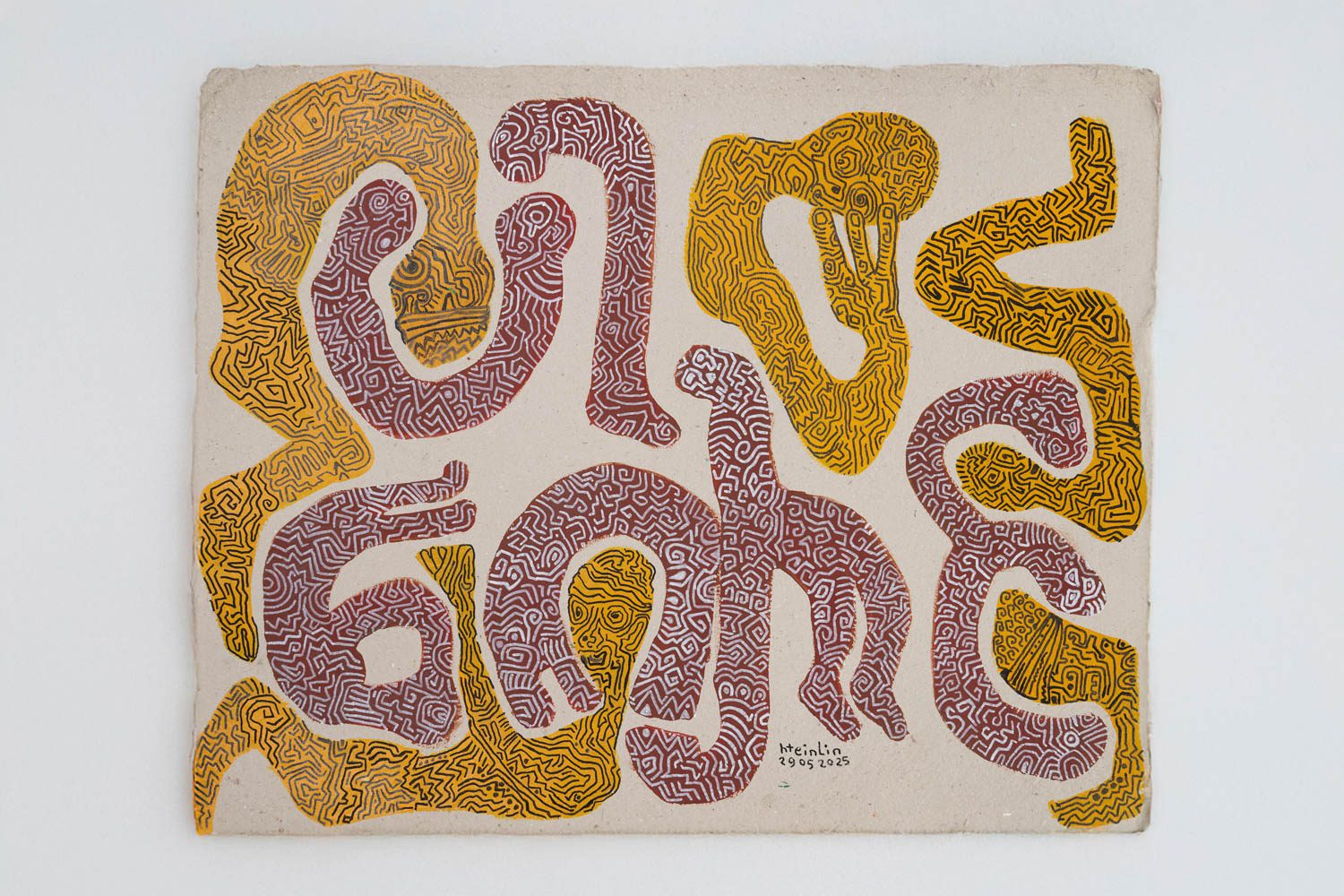

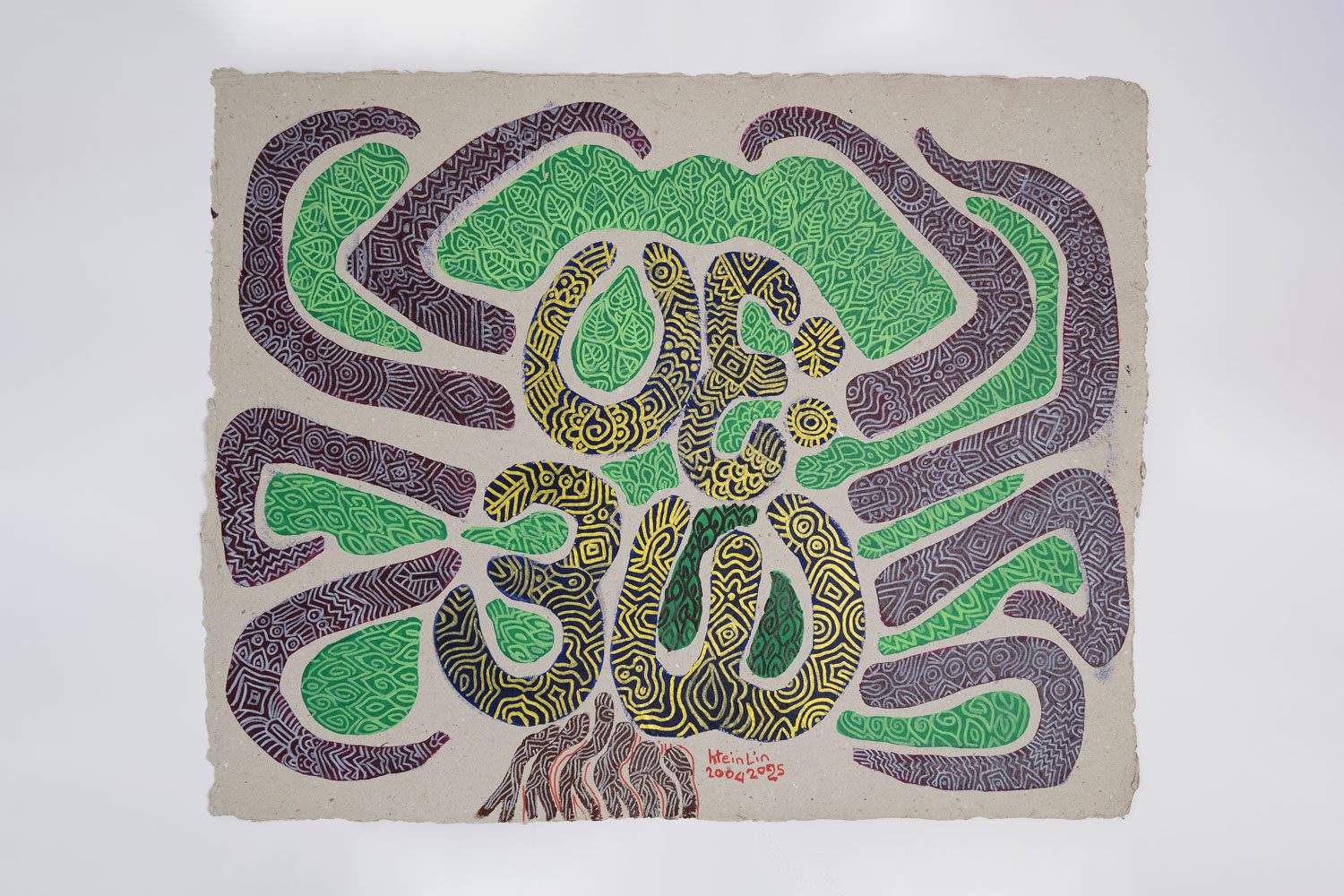

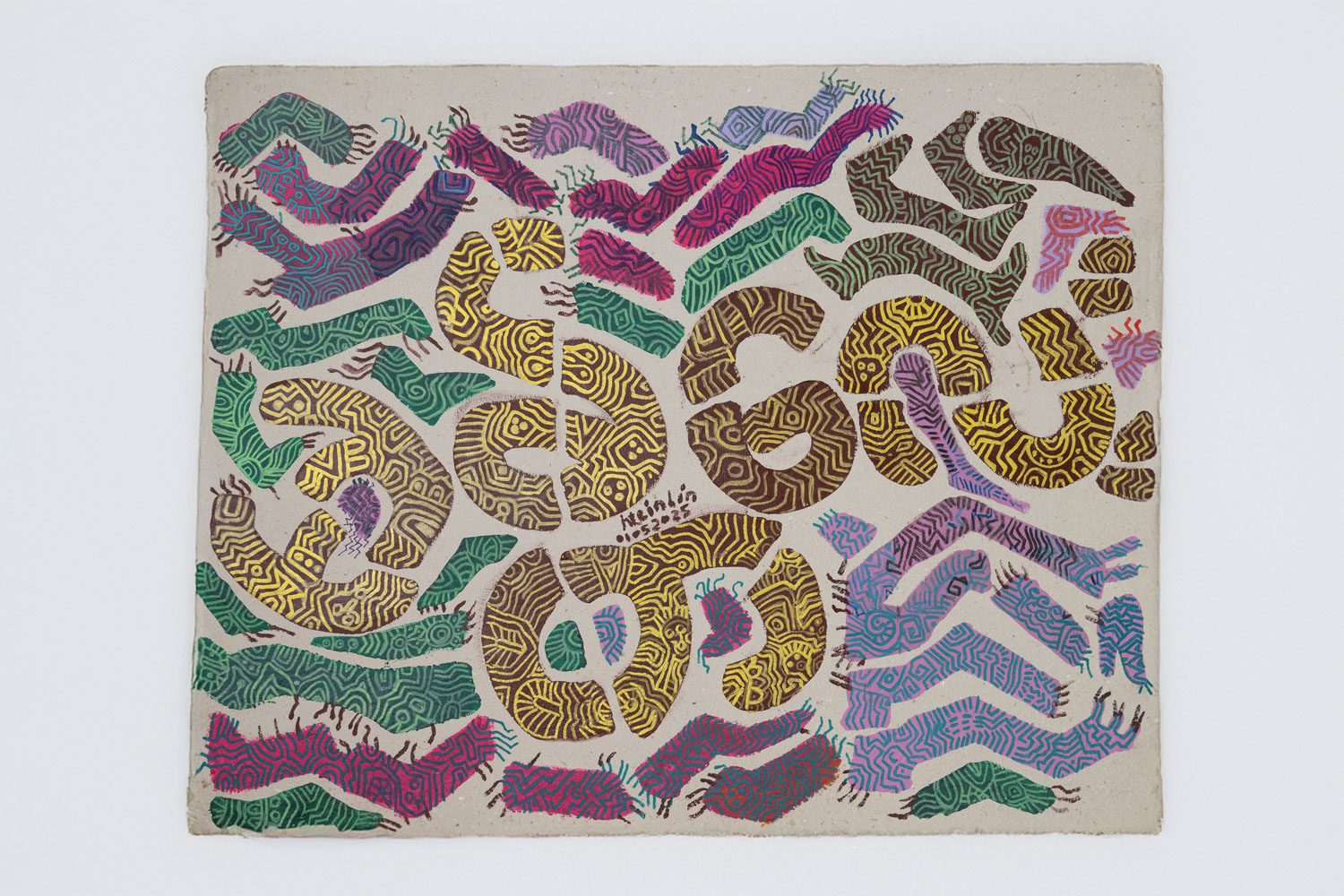

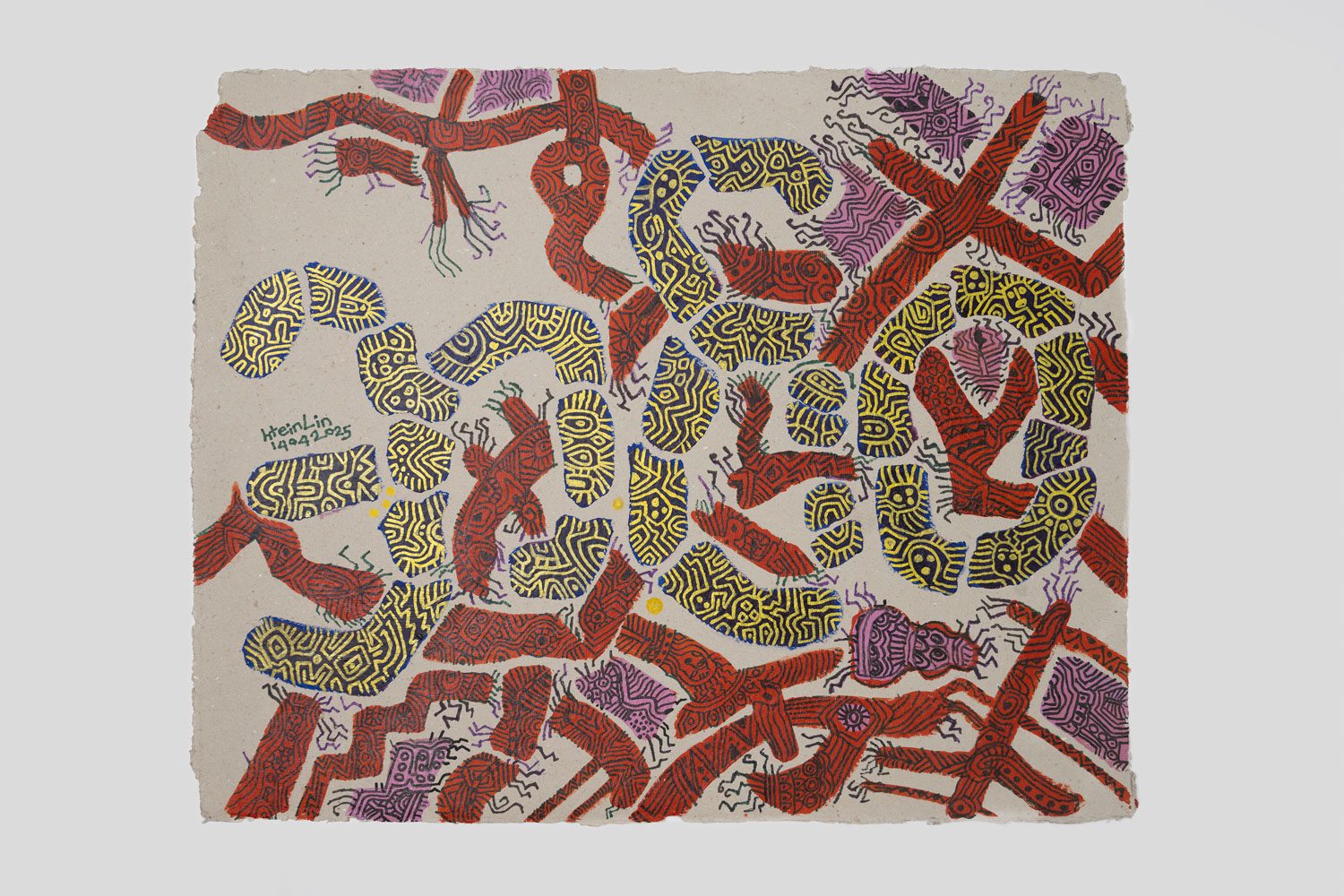

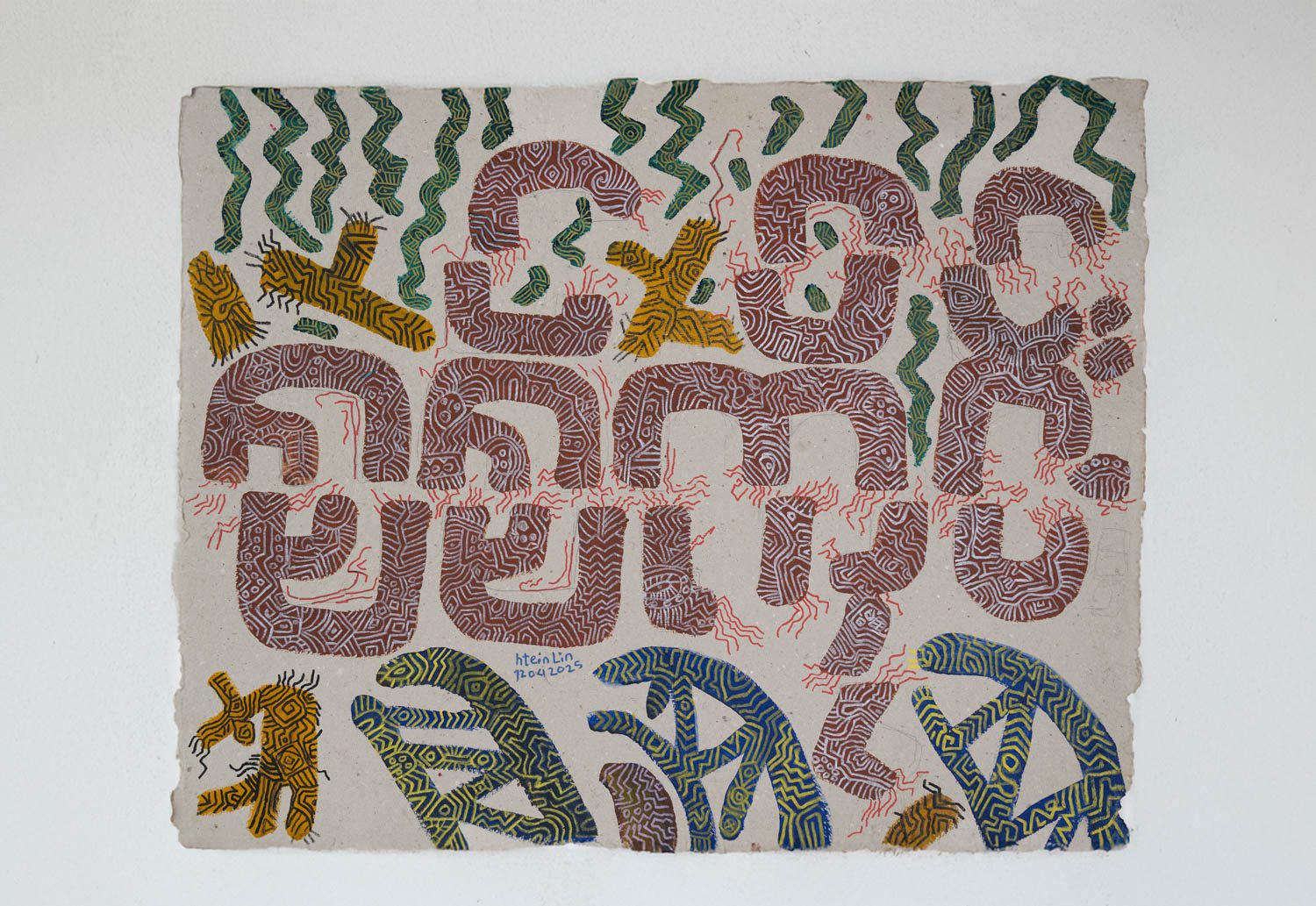

For the exhibition ‘အက္ခရာ’ (Ek Kha Ya), Htein Lin, artist, former political prisoner, and one of the student activists involved in the 8888 Uprising,3 selected letters, words, and phrases that evoke the violence between state and citizen, reworking them into drawings on cardboard. Each Burmese character is inscribed and layered with images of brutality, symbols, and meanings, superimposed upon its original linguistic form. In doing so, words and images merge, reinforcing one another to ‘call’ and ‘cry out’ against what has so often been forced into ‘silence.’

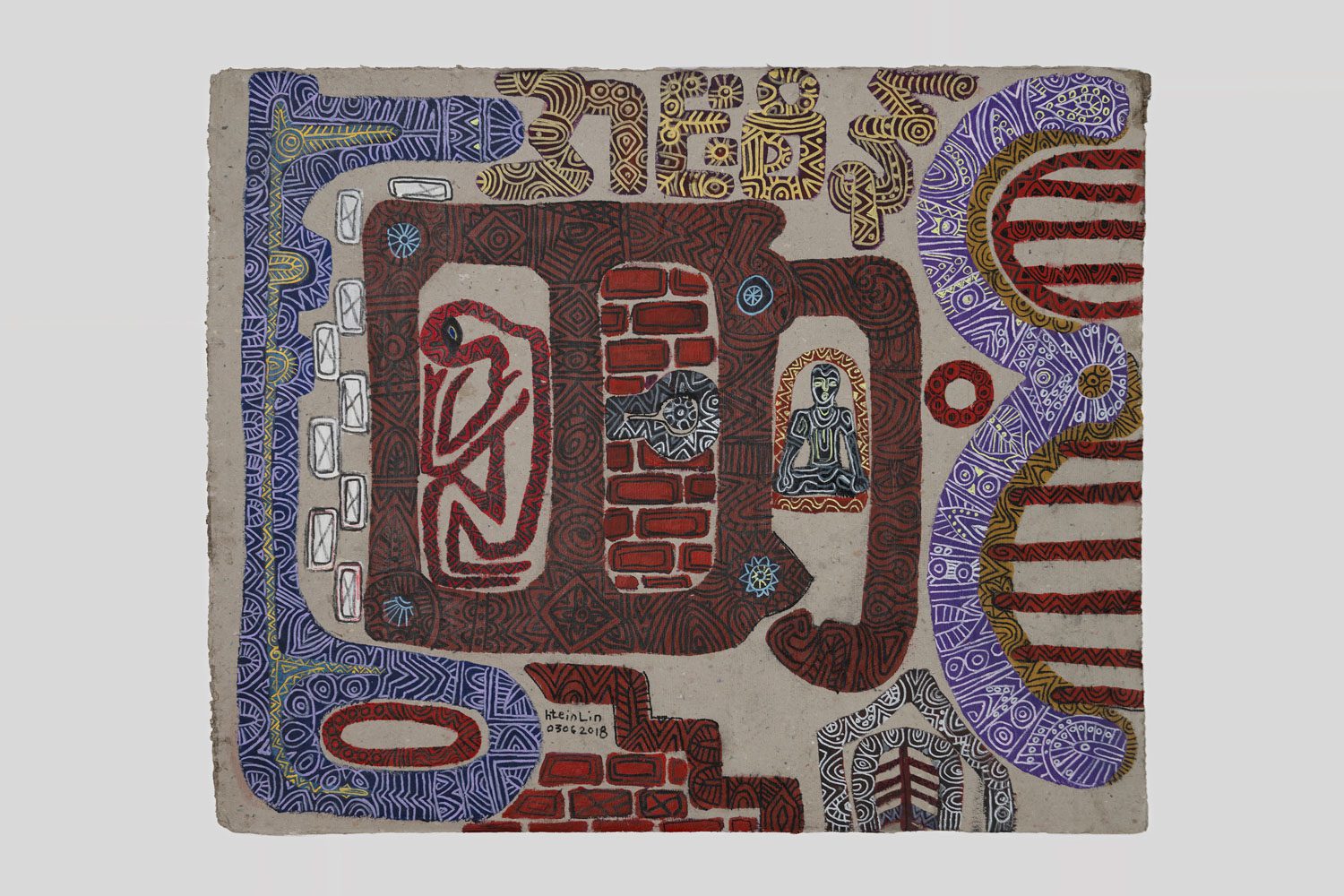

In ‘Insein Prison’ (2018), Htein Lin transforms the name of Insein Prison, ‘အင်းစိန်ထောင်’ (Insein Htaung), into a visual representation of the very institution that confines Myanmar’s citizens. The artist twists the letters of the prison’s name so that they themselves become the image of the prison itself. The curves on either side of the word and the tower at its center mirror the architecture of the facility: a panopticon designed to exert control through spatial organization. From its central watchtower, every movement of the inmates could be monitored.4

Htein Lin, Insein Prison, 2018 | Photo courtesy of Htein Lin

Insein Prison | Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Insein_Prison#/media/File:Insein_Prison_2.JPG

It is notable that the artist does not attempt to render the floor plan of Insein Prison with absolute precision, as though producing a replica of the facility. Nor does he transform the name ‘အင်းစိန်ထောင်’ (Insein Htaung) into a decorative piece of calligraphy. Instead, it is the convergence of image and word that allows the work to expand meaning beyond what either could achieve alone. Htein Lin pares back certain features, leaving only a trace, before layering in a skeletal framework that binds text and image together.

This can be seen in the motifs that wind their way through the frames of the letters and/or along the walls of the prison. Many of these forms can be discerned as plants, flowers, and animals. In some places, one even recognizes the figure of the peacock—a symbol of the Burman ethnic majority, long the dominant force in Myanmar. Because such motifs do not actually appear carved into the prison walls themselves, the work reveals what cannot otherwise be seen with the naked eye, made visible through painting. Htein Lin shows how both the prison’s walls and the edges of the letters are inscribed with narratives of struggle, oppression, and the pursuit of freedom. At the same time, the dense patterns along the borders recall ancient mural paintings, where stories were embedded in ornamental lines and forms, playing with the progression from line to letter, and, conversely, unraveling the letter back into line.

By rendering what is ‘difficult to speak’ into ornamental patterns, Htein Lin also plays upon the very mechanisms of an authoritarian state: its surveillance, its censorship, and its silencing of dissenting voices under the pretext of national security. The image/word of Insein Prison therefore extends beyond a depiction of the prison itself. Even though the surface of the paper bears only the name of this notorious institution, Htein Lin’s work prompts us to reflect on the divide between life inside and outside the prison walls, a boundary that, in many cases, seems no more than a line of bricks. For beyond the prison, citizens are subjected to controls on thought and expression that differ little from confinement itself. Insein Prison, then, is not merely an unveiling of lives restricted within its walls, but equally an exposure of lives outside, where freedom is systematically eradicated.

At the same time, Htein Lin’s work does not simply illustrate how dominant power renders people blind and mute. On the contrary, ‘အင်းစိန်ထောင်’ (Insein Htaung), transformed into the form of a prison, still retains its outline and can still be read as a word. Though not a literal, one-to-one transcription, Insein Prison speaks as forcefully as any direct account of memory or pain. His work thus reveals how words are ‘under the spell’ of the state, while simultaneously resisting authority by becoming ‘spelled’ anew—made visible to the world through artistic practice. This is further evident in other works from the same series included in the exhibition, where Htein Lin selects words that satirize, words that allude to corrupt power, and words that expose the incapacity of an authoritarian state to govern. Among them are the names of towns struck by the major earthquake along the Sagaing Fault in central Myanmar earlier this year.

Photo courtesy of Htein Lin

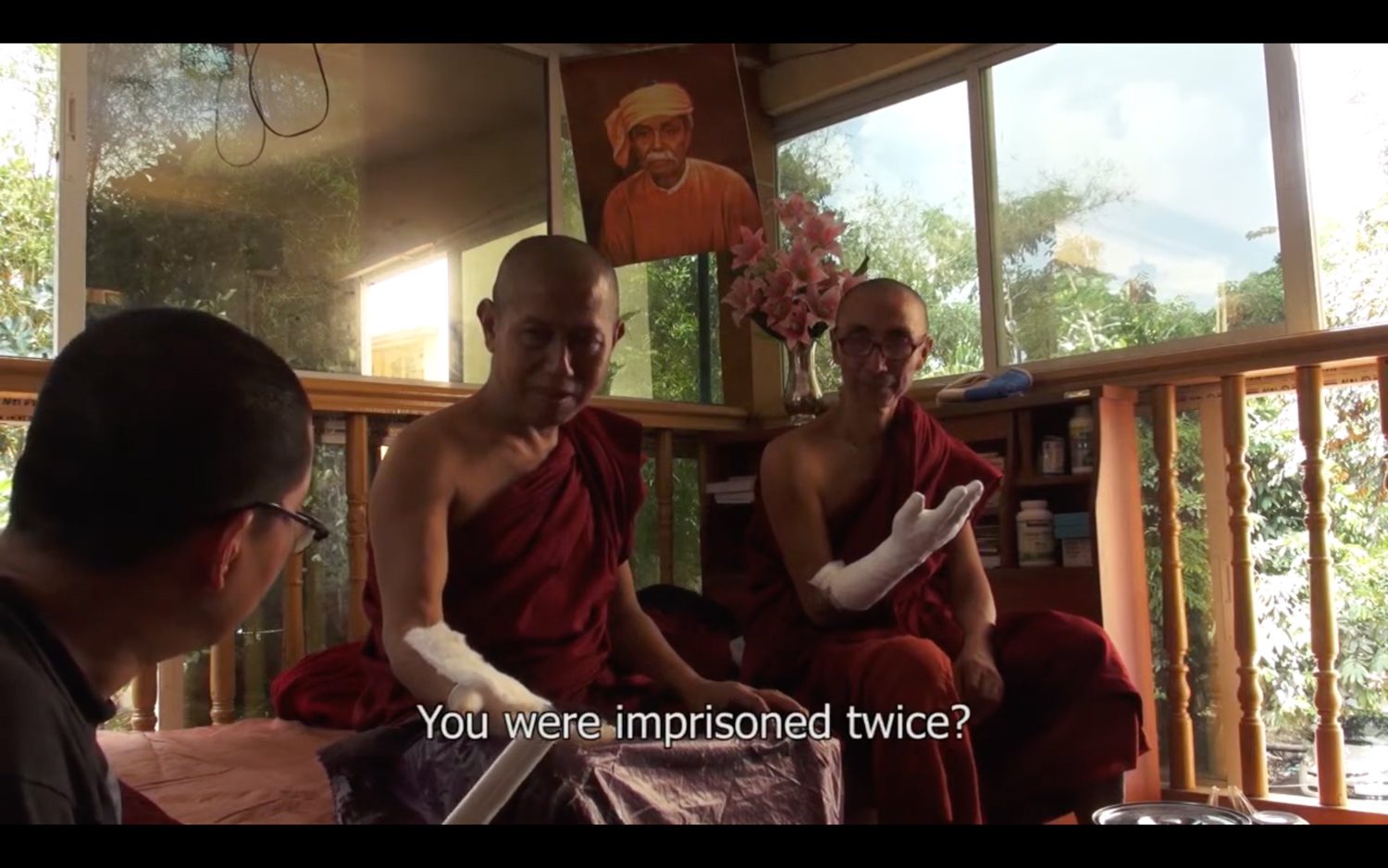

Beyond narrating life inside prison, the exhibition also presents ‘A Show of Hands,’ Htein Lin’s long-term project that began in 2013 and continues to this day. For this series, he has traveled to meet former political prisoners who have returned to life outside prison. Their stories are documented through an archive that records the charges they faced and the length of their imprisonment, accompanied by video interviews that capture conversations about wounds and hopes, as well as plaster sculptures cast from the hands of those who have rejoined society. The project draws on Htein Lin’s own experience of once breaking his arm and wearing a cast, transforming the themes of fracture, repair, and healing into a body of work.

Although it takes place outside the prison walls, the work points to the processes of violence within, processes that attempt to create a form of forgetting that does not end when the sentence is served. As a result, when former political prisoners return to society, many choose to live quietly, avoiding any renewed confrontation with the violence of incarceration. Their names, histories, and suffering eventually fade from public memory, weakening long-term resistance or opposition to the state’s dominant power.

Htein Lin’s work stands against such erasure. Through documentation, the systematization of archives, and the practice of art, he gathers the violence inflicted by the state and renders it into both words and images. It is notable that his project inverts the state’s own procedures, which so often rely on fabricated evidence to portray dissent as a crime. In contrast, ‘A Show of Hands’ becomes evidence that reveals the state itself as the perpetrator of violence. The choice to cast the hand is therefore a deeply significant act, underscoring that no matter how absolute the power of a military regime may appear, there remain countless hands that rise to resist the injustices it produces.

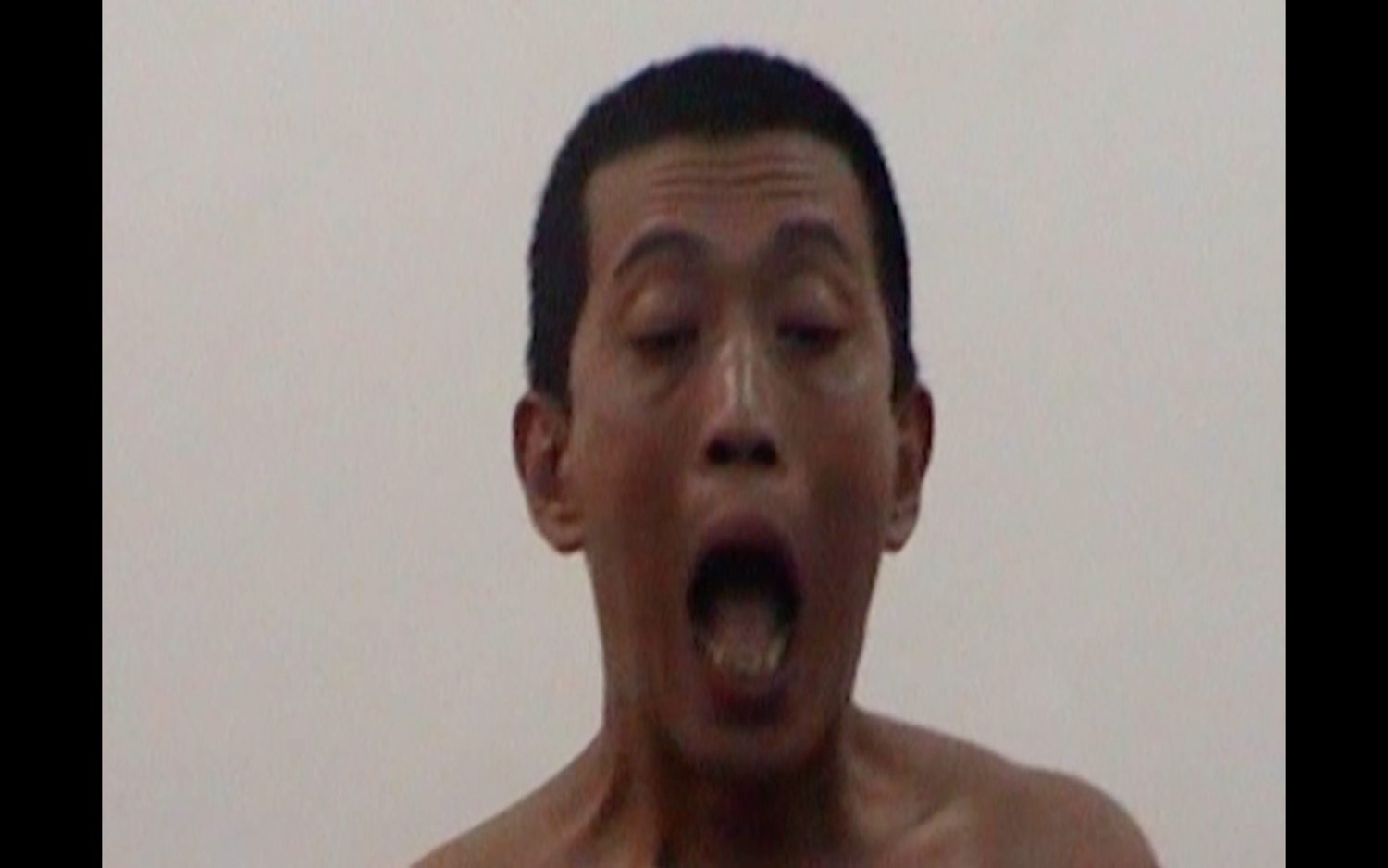

The critique of the state, the prison, and the restriction of freedom continues in ‘Fly’ (2005), a video recording of a live performance presented opposite the image of Insein Prison. The work is screened on a small monitor placed inside a black cage, showing Htein Lin with his hands clasped behind his back like a prisoner in handcuffs. He struggles against the flies that circle and land upon him. However bothersome they may be, he cannot easily swat them away, as his hands are bound by invisible restraints.

The metaphor that emerges between fly and prisoner is not far removed from the spectacle of violence between the Myanmar state and its citizens. Flies, often associated with filth, decay, and contamination, are to be eradicated and driven out. Yet here, the right to swat, to cleanse, and to flourish is stripped from the people altogether. In turn, the chance and the hope for change vanishes like a dream, leaving everything before them clouded, caught in an endless cycle of rot.

The state thus confines not only lives but the future itself…

The exhibition ‘အက္ခရာ’ (Ek Kha Ya) is on view at West Eden: Contemporary Art from August 20 to October 12, 2025.

_

1 Myanmar has been recorded as the modern state with the world’s longest-running civil war. See also Guinness World Records (2013, December 31). Longest civil war of modern times. Retrieved from https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/114580-longest-civil-war-of-modern-times

2 Although General Ne Win resigned as party leader following the ‘8888 Uprising’, conflicts between the Burmese government and its people have continued to erupt repeatedly in the years since. These include the military’s refusal to recognize the results of the 1990 election, won by Aung San Suu Kyi, which ended with her being placed under house arrest, as well as the 2021 coup led by General Min Aung Hlaing that once again ignited mass protests across the country

3 West Eden. (n.d.). Htein Lin – Biography. Retrieved from https://www.westedenbkk.com/artists/97-htein-lin/biography/

4 See Insein Prison, the Panopticon Model, and the Dire Welfare of Prisoners in Lalita Hanwong. (July 30, 2021). Prison Riots and the Reflection of a Failed State in Myanmar. Matichon. Retrieved from: https://www.matichon.co.th/columnists/news_2856888